Stuart Lake’s legendary Wyatt Earp has more cachet among collectors than the real man behind the gun.

Stuart Lake’s legendary Wyatt Earp has more cachet among collectors than the real man behind the gun.

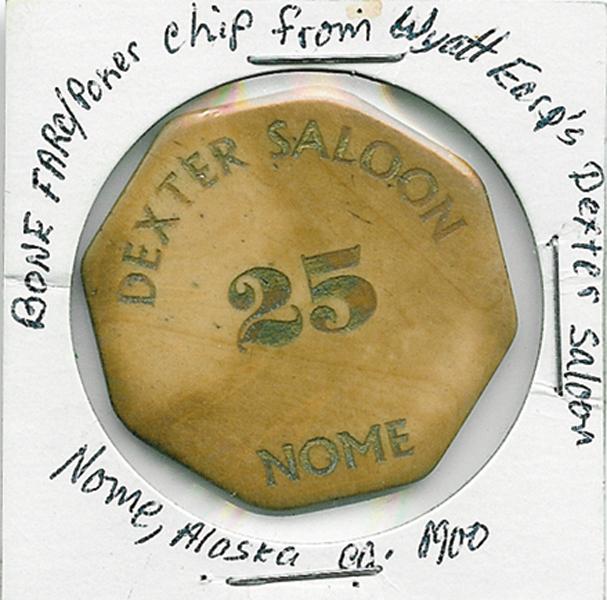

When presented with the Earpiana collection of the late John Gilchriese at Johns’ Auction Service on February 18, bidders clamored for tangible items that Wyatt is believed to have touched: his two-blade, folding pocketknife by Imperial Knife Co., circa 1920s; a poker chip from Wyatt’s Dexter Saloon in Nome, Alaska; the knife with which he ate his last meal. The highest bid went to an O.K. Corral gunfight map drawn by Wyatt’s own hand.

But not many collectors saw as treasure the pages and pages of letters between John Flood, Jr. (stenographer for Wyatt’s first autobiography) and Wyatt’s wife Josephine Marcus. Much of the correspondence reveals a woman attempting to climb out of genteel poverty by cultivating her husband’s fame while at the same time, making him respectable. Her letters show she wanted laurels made out of Wyatt’s years as a prospector and businessman, not his gunfighting days.

Despite Josie’s censure attempts on Flood’s manuscript, she was trying to bring to light a side of her husband not many saw. For Gilchriese, Flood’s manuscript notes must’ve seemed like a gold mine. He discovered their existence after coming across a June 6, 1931, letter to The New York Times, in which Flood admits “I have the stenographic notes of the story of Wyatt Earp, just as Mr. Earp dictated them to me a few years ago.” When Gilchriese finally tracked down Flood and held those notes in his hands, he was the closest to Wyatt he had ever been in his life.

But did Gilchriese get it right when he said “Silver made Tombstone rich. Wyatt made it famous”? For him, it may have been a thrill to read the lawman’s life story told in his own words, but today’s collectors ignored Flood’s notes, as if to say Wyatt’s life doesn’t matter beyond his Tombstone years. Sure, they’ll bid for a trinket that the Tombstone gunfighter may have touched. But, as the auction results reveal, collectors want to remember Stuart Lake’s frontier marshal, not a man who wasn’t best buds with Doc Holliday, wasn’t “always for law and order” and was so poor he couldn’t even afford the funds for a 50-copy requirement that would’ve accorded his autobiography copyright protection (and in doing so, may have prevented the publication of Walter Noble Burns’ Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest, which would become the first to reveal Wyatt’s intimate connection to the town too tough to die).

Wyatt may have made Tombstone famous, but today’s collectors are saying the trappings of the real man could never measure up to his legend. They refuse to sever Wyatt from his 27 seconds of fame. The items that preserved their gunfighter ideal garnered over $60,000 in bids.

Photo Gallery

-All images courtesy Johns’ Western Gallery-

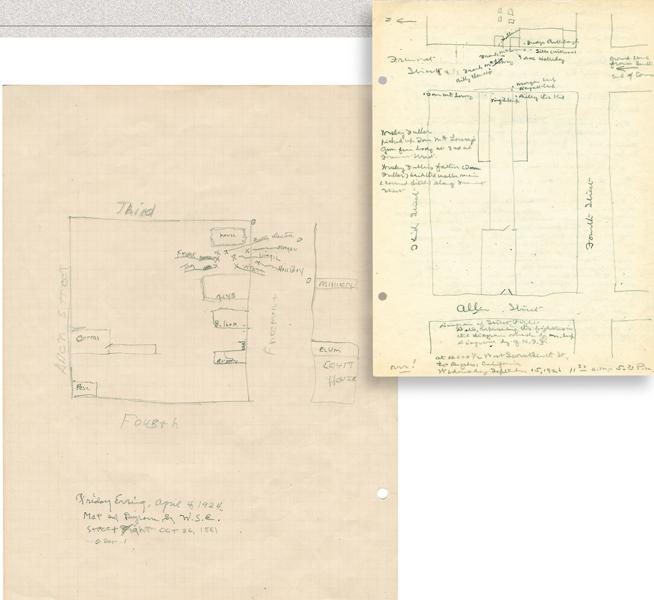

For many Wyatt Earp fans, a mere 27 seconds define his life. In 1924, 76-year-old Wyatt drew a map of the October 26, 1881, O.K. Corral gunfight, which is supplemented with notes by Wyatt’s secretary, John Flood, Jr. Wyatt’s map (left) sold for $40,000. In June 2004, Johns’ Western Gallery sold a 1926 map drawn by Flood (inset) for a $100,000 bid.

Wyatt’s map correctly shows where the gunfight was located, marking with an X the location of all the participants at the beginning of the fight—between C.S. Fly’s photography gallery and Harwood House—while the dots indicate where the three cowboys died (Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury’s bodies on Fremont Street; Tom McLaury’s on the corner of Fremont and Third). Flood’s map, however, places the gunfight behind the O.K. Corral’s entrance, relegating the fight to its legendary location.

For years, Earpiana historians have wondered how Wyatt could have misremembered the location, attributing the mistake on Flood’s map to Wyatt’s old age or the fact that the fight had taken place 45 years before. This find reveals that Wyatt was sharp as ever. It was his secretary who couldn’t take notes.