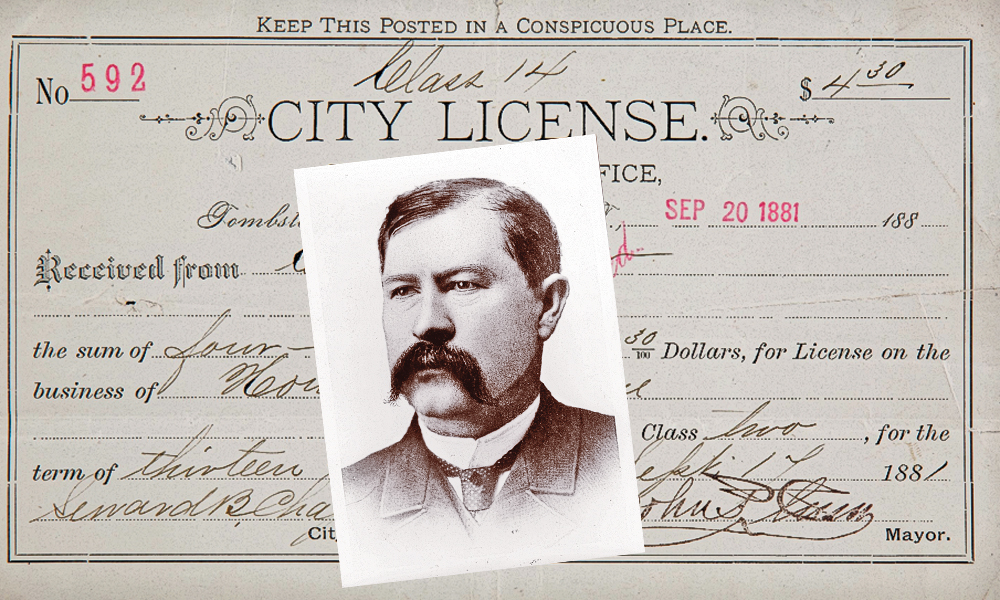

The most celebrated Thunderbird encounter took place in 1890, on the desert sands of what was then the Arizona Territory. Two cowboys had a bizarre confrontation which has varied widely in the telling, but the gist of the story is this: they saw a giant flying bird, shot and killed it with their rifles, and carried its spectacular carcass into town.

A report in the April 26, 1890, Tombstone Epigraph listed the creature’s wingspan as an alarming 160 feet, and noted that the bird was about 92 feet long, about 50 inches around at the middle, and had a head about eight feet long. The beast was said to have no feathers, but a smooth skin and wingflaps “composed of a thick and nearly transparent membrane… easily penetrated by a bullet.” Perhaps the hardest part of this story to swallow is that two horses could manage to haul a dead behemoth like this for any distance.

Sounds like a typical tall tale of the Wild West and that’s probably what it is. But it apparently does contain a kernel of truth. In 1970, Harry McClure claimed that as a boy he knew the two cowboys from the story later in their lives, and they had told him a different version of the events. McClure said the giant bird they saw in the desert actually had a wingspan of more like 20 to 30 feet – much more reasonable than 160, but still enormous. The two riders shot at the creature, but it was out of range. Their spooked horses refused to chase it, so the men rode into town empty-handed, carrying only news of the one that got away.

The Tombstone newspaper printed its highly embroidered version of the cowboy’s sighting, which was spared from fading into obscurity by its inclusion in a 1930 book on the Old West. In 1963, the story came to the attention of writer Jack Pearl, who revived the tale for an article in a pulpy men’s adventure magazine called Saga. As if the Epigraph report hadn’t spiced up the facts enough already, Pearl liberally embellished the encounter into a dramatic rip-snorter entitled “Monster Bird That Carries Off Human Beings!”

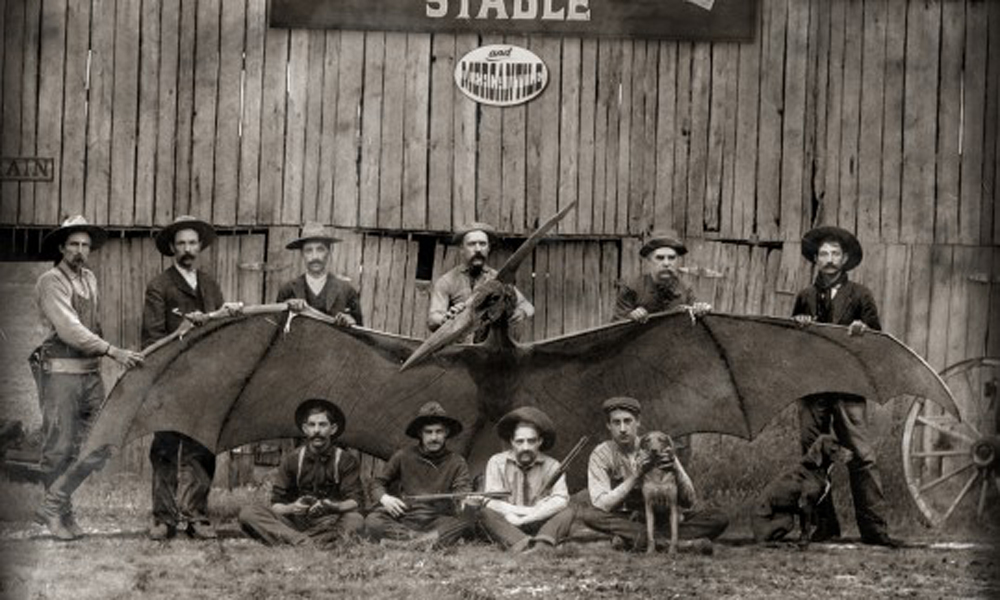

Pearl pushed the date of the encounter back to 1886, and he described the witnesses as two prospectors who killed the bird and proudly showed off their trophy in Tombstone. Pearl also added some extra conflict by telling of a how a second Thunderbird snatched up a heckler who had ridiculed the prospectors and flew away with him in its talons. But Pearl’s most significant editorialization was this: he said that the Epigraph newspaper story had run with a photograph of the giant bird’s carcass, nailed up to a wall with its mighty wingspan unfurled, and a number of men posing next to it for scale.

This part of the legend, the Thunderbird photo, has taken on a life of its own. Pearl’s fictional account of a photograph of Old West settlers with a big dead bird was picked up and repeated time and again, multiplying and evolving just as it had before Pearl ever got hold of it.

In time, people who heard the story began to believe that they had previously seen the photo with their own eyes. Somehow, people felt convinced that they had once marveled at the strange picture in some old book or newspaper, often noting that they didn’t realize the significance of the photo at the time, and regretting that they had not kept it. The details might differ from one recollection to the other, with some recalling the bird had feathers and others saying it looked more like a pterodactyl, and some thinking the bird was nailed to a wall and others remembering that it was held with wings outstretch by a large group of men. But no matter what the specifics, each person feels certain his or her memory is true.

Many have reported that they saw the Thunderbird photo in FATE, National Geographic, Grit, or some other similar publication, but entire archives of these periodicals have been searched, and no Thunderbird discovered. The experts in the cryptozoology field are no less susceptible to Thunderbird recollections than the common layman, with Ivan T. Sanderson and John A. Keel among those who claim to have once held the photo in their hands. Some accounts of seeing the photo are amazingly precise and hard to disregard.

It’s difficult to tell someone that an experience as vivid as that never really happened, but what is the alternative? What’s the word with the Thunderbird?

The best explanation for the phantom photo phenomenon is that these are memories of things that never existed. It might simply be that people have read descriptions of the cowboys and the giant bird that were so colorful and evocative that their imaginations created a near-tangible mental image of the scene. As the controversy surrounding ‘false memory syndrome’ has demonstrated, the things we think we recall can be distorted by external suggestion, mismatched fragments of things that did happen, and maybe even debris from the collective subconscious. Some might view this line of reasoning as party-pooping skepticism, but if it’s correct, what it reveals about the mysteries of the human mind is way more interesting than any big bird could ever hope to be.