The Missouri River northwest of Bismarck, North Dakota, is not the same river explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark saw in 1805, even though it has the same name. Much has changed in two centuries.

The Missouri River northwest of Bismarck, North Dakota, is not the same river explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark saw in 1805, even though it has the same name. Much has changed in two centuries.

When Lewis and Clark wintered with the Mandans in 1804-05, the tribe was still reeling from the smallpox epidemics that had devastated the Upper Missouri in 1780-1781 and 1801-02 (in 1837-38 yet another smallpox epidemic would all but wipe out this tribe that had once controlled much of the trade on the Northern Great Plains).

In the spring of 1805, the Corps of Discovery left the Mandans and neighboring Hidatsas, heading up the Missouri, accompanied by Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshoni wife Sacagawea, and their infant son Baptiste.

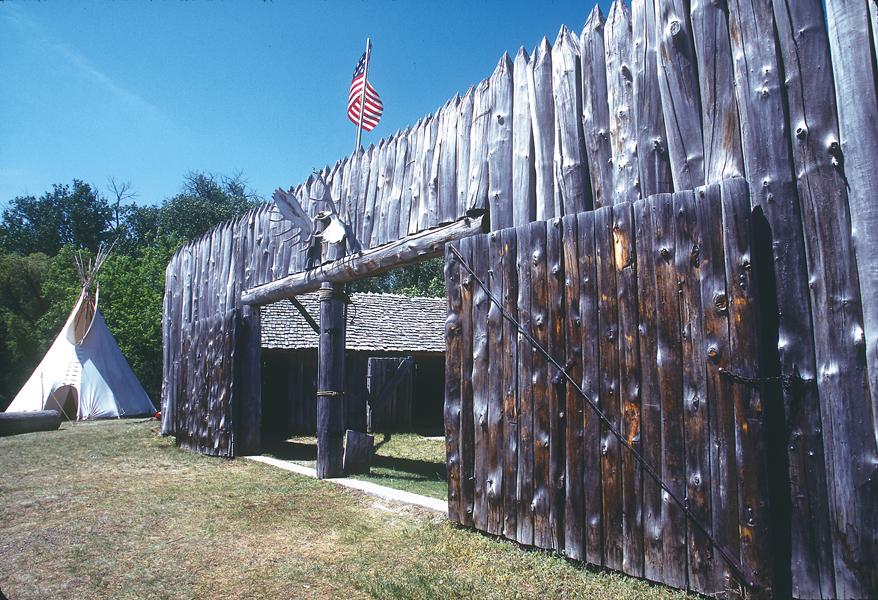

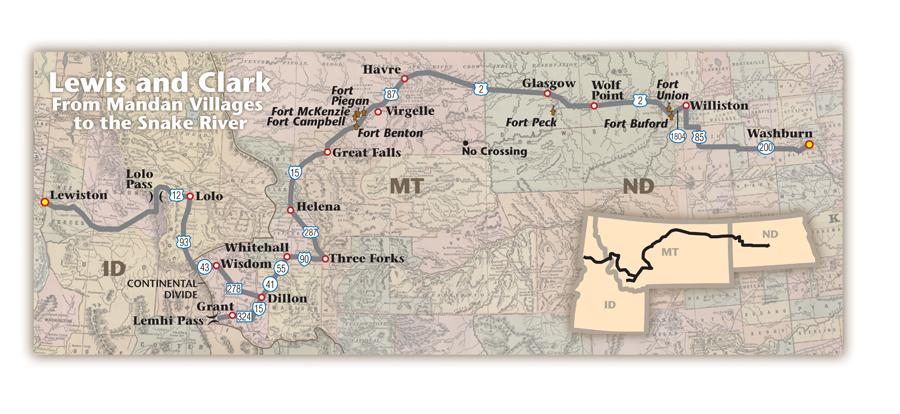

Fort Mandan Historic Site and Visitor’s Center, two miles west of Washburn, is a good place to begin a trip following the Corps from the Mandan Villages to Lemhi Pass, across the Bitterroots and along the Clearwater River to the Snake.

Leaving Washburn, I take North Dakota Highway 200 west to U.S. 85. I follow that road north to cross the Missouri just west of Williston where I turn west to Fort Buford, and not far from there, the impressive Fort Union. Both were fur trade and frontier military-era supply posts established in the wake of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Entering Montana

A few miles more and I cross an unseen boundary to enter Montana where Lewis and Clark spent 170 days on their west and east bound journeys. Following the river on U.S. Highway 2, I travel to Wolf Point, passing through farming country that at the time of the explorers was inhabited by buffalo, grizzly bears and even wolverines.

At Fort Peck, I realize why the Missouri seems so tame downriver: Fort Peck Dam. It backs up into the lake of the same name, encompassing miles of the Missouri and is now a part of the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge. There are roads running closer to the Missouri in this portion of Montana, but I opt for the highline and follow U.S. 2 through Glasgow and Havre before turning southwest where I am again within striking distance of the Missouri at Virgelle.

To be real honest here, I do rivers about as well as True West contributing editor Johnny Boggs does helicopters (Boggs admitted his fear of helicopters in the September 2004 Road Trip feature), which is to say I don’t like ’em. But if you truly want to experience a part of Montana that is much as Lewis and Clark saw it, this stretch of the Missouri—between Fort Benton and No Crossing—is the place to do it. Tour companies can get you on the river, or with proper permits, you can float it on your own. I stick to Highway 2, stopping at Virgelle Ferry for a short break.

One result of the expedition was the American entry into the fur trade along the Upper Missouri. Upstream from Virgelle are sites of some of the first forts established in Montana to serve that trade. The earliest posts were Fort Piegan, established in 1831, and Fort McKenzie, in late 1832, both built for the American Fur Company. Other forts later established to capitalize on the Upper Missouri fur trade were Fort Fox and Livingston, Fort Campbell, Fort Lewis and Fort Benton.

I find Fort Benton fascinating, not only for its Lewis and Clark connections, but also for its role as the center of trade in Montana in the first century following their journey. Eventually, steamboat traffic made its way up the Missouri to Fort Benton to disgorge freight and passengers headed either into Montana Territory after the 1864 gold discoveries at Alder Gulch, into Canada via the Whoop-up Trail or toward the Columbia Basin along the Mullan Road.

Today, Fort Benton—a gateway to the Upper Missouri National Wild and Scenic River—is anchored by the Grand Union Hotel and several historical attractions including the Museum of the Upper Missouri, Historic Old Fort Benton and the Museum of the Northern Great Plains.

Great Falls and Mountain Gates

Upstream from Fort Benton, Lewis and Clark faced the unharnessed power of a big river in early season high water and the Great Falls of the Missouri. Unable to continue on water, they resorted to a portage. It was a grueling ordeal and once they had bypassed the Great Falls, the explorers allowed their men a period of rest. I also find this is a good place to take a break from driving and spend a couple of days exploring the area. The first and obvious stop is the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center located beside the river with walking paths and rich displays. But Great Falls has much more to offer a modern traveler, for this is also the home of Charlie Russell’s art studio.

Leaving Great Falls, I take Interstate 15 to Helena. Dark granite rocks loom above the Missouri River outside Montana’s Capital City, where on July 19, 1805, Sgt. John Ordway observed, “this curious looking place we call the Gates of the Rocky Mountains.”

Those gates beckoned the expedition members as they sensed they were nearing the Rocky Mountains. They hoped they would soon not only reach the divide and the Columbia River drainage leading to the Pacific, but also locate Shoshoni Indians from whom they could obtain horses.

But the high walls of the canyon were only a tantalizing taste of the Rocky Mountains. It would be weeks before Lewis and Clark reached the genesis of the Missouri River. Today, a tour boat company operates on the Missouri through Gates of the Mountains. Travelers are likely to see bighorn sheep and Rocky Mountain goats scrambling on the rocky hillsides; tourists can have a picnic or hike at Meriwether Picnic Ground, where Lewis himself likely camped one night.

By the time they got here, the Corps members had drunk the last of their whiskey and had not seen one local native inhabitant since entering the land that is now Montana.

Once through the mountain gates, Lewis followed the Missouri upstream; Clark traveled overland in the region and never actually saw the river gates. The two rejoined forces at a significant site on their trail: Three Forks. This is a perfect place to spend a night (take U.S. 287 from Helena to Three Forks), staying in the Sacajawea Hotel. You can relax in a rocking chair on the long porch—something Clark would have appreciated as he recuperated from an illness in this area—and take the short drive to Missouri Headwaters State Park where the three rivers that form the headwaters of the Missouri join. The explorers named the forks the Gallatin, Madison and Jefferson Rivers. Today, there are hiking trails along the rivers that overlook their confluence.

Laboring up the Jefferson

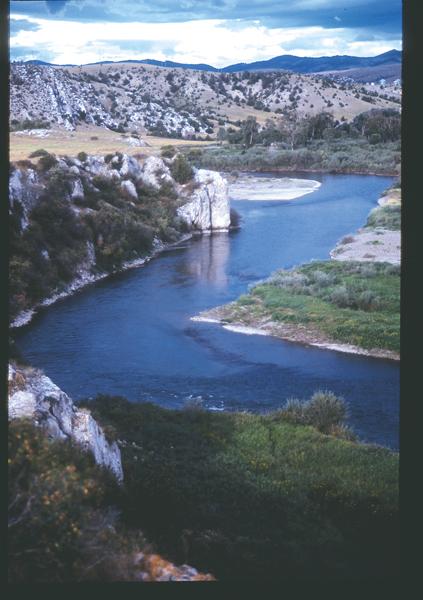

Leaving Three Forks, Lewis ventured on ahead seeking Indians while Clark and the majority of the men labored up the Jefferson. The river ribboned its way in oxbow curves through the valleys and gradually became shallower, making travel slow and difficult.

The men spent most of their time in the water pushing and pulling their boats. Some days they traveled up to three river miles just to gain one land mile. They wanted to abandon the boats and proceed on land, but couldn’t carry all of their equipment and supplies if they had done so. Therefore, they trudged on—wet, exhausted, often ill.

In generally following their route, I take Interstate 90 west from Three Forks to Whitehall, then turn southwest on Montana Route 41 to Dillon, where I pick up I-15 and follow it south to Clark Canyon Reservoir, then west on Highway 324 toward the tiny community of Grant and eventually Lemhi Pass, on the Montana-Idaho border.

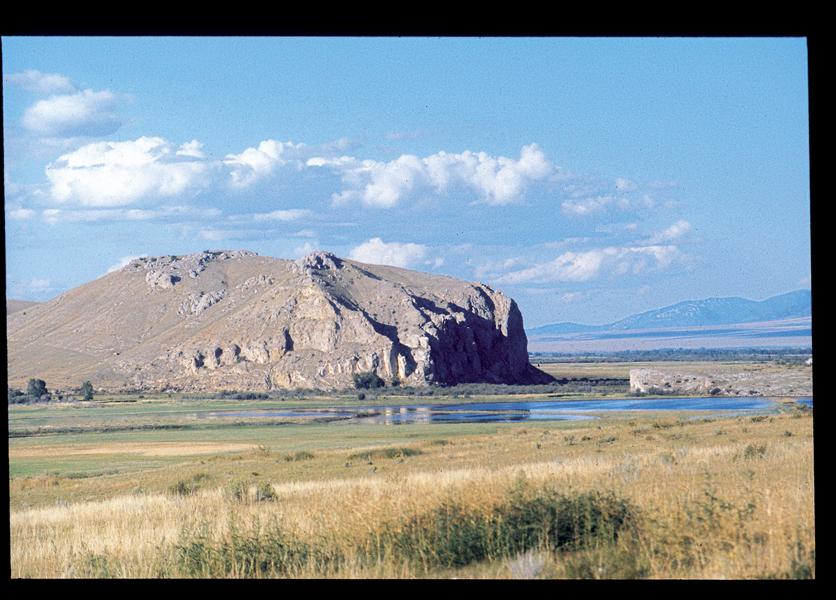

On August 8, 1805, Sacagawea pointed out a prominent landmark her people called the Beaver’s Head. Today, it is called Beaverhead, and you will pass it when traveling Route 41. When the party reached Beaver’s Head, Lewis took three men and forged ahead looking for Indians. Farther to the west, near Grant, in a long valley known today as Horse Prairie, on August 11, 1805, Lewis and his companions saw their first Indian other than Sacagawea since entering Montana. Their efforts to talk with the man failed when he was frightened away.

The following day, Lewis and his companions followed the Jefferson to its beginning. On that momentous occasion, Lewis said, “Private Hugh McNeal exultingly stood with a foot on each side of this little rivulet and thanked his God that he had lived to bestride the mighty and heretofore deemed endless Missouri.”

Shoshoni Range

At Lemhi Pass, Lewis and his com-panions crossed the Continental Divide and descended into today’s Idaho, traveling toward the Salmon River and the known range of the Shoshonis. Fortunately for the explorers, the next day—August 13, 1805—Lewis encountered more Indians, this time successfully convincing them to take him to their village, where he not only conveyed his desire to purchase horses for the expedition, but he also persuaded the chief and his people to go with him back down the Jefferson River to meet with Clark.

On August 17, Clark reached the location since known as Camp Fortunate, where Lewis and the Indians were waiting. (Camp Fortunate is now covered with the waters of the Clark Canyon Reservoir.) The events that transpired there would change the expedition’s fortunes for the captains negotiated for horses by exchanging trade goods. Clark then set off separately from Lewis, determined to see if the river just over the divide at Lemhi Pass—the Salmon—could be followed by boat. He found it too difficult to navigate, and ultimately the two captains decided to purchase horses in adequate numbers to make the journey across the Bitterroot Mountains.

They followed the Bitterroot River to present Lolo, Montana, where they turned west again crossing the Bitterroot Range at Lolo Pass over the long used, but extremely difficult to negotiate, Nez Perce Trail. In following their course, I take highways 278 northwest from Dillon to Wisdom, Route 43 west to U.S. 93 and then follow it to Lolo, where I turn west on U.S. 12, which I will follow to Lewiston, Idaho.

Interlude with Nez Perces

In spite of the horses, the explorers traveled slowly and they suffered significantly. Snow buried the trail and they couldn’t find game, so they nearly starved, killing horses for food as they became desperate.

Eventually they met members of the Nez Perce tribe near Weippe Prairie and at the river that they called Kooskooske (pronounced koos keich keich), the present-day Clearwater River. The Corps remained there—at a place since known as Canoe Camp—until October 7, during which time they felled massive Ponderosa pines, burning and scraping them to form dugout canoes. They left their animals in the care of men from Twisted Hair’s village, pushed the canoes into the Clearwater and began the last leg of their journey, following the Clearwater to its confluence with the Snake at present Lewiston, Idaho.

Their interlude with the Nez Perces was fortunate. Not only were the explorers given food that helped them recuperate from a grueling journey over the Bitterroots, but they also obtained important information about what to expect as they continued on their trip toward the Pacific Ocean.

Photo Gallery

Clark’s journal entry, July 25, 1805: “a fine morning we proceeded on a fiew miles to the three forks of the Missouri those three forks are nearly of a Size, the North Fork (later named the Jefferson River) appears to have the most water and must be Considered as the one best calculated for us to assend. I wrote a note informing Capt. Lewis the rout I intended to take, and proceeded on up to the main North fork thro’ a Vallie, the day verry hot.”

– By Candy Moulton –

Lewis’ journal entry, August 8, 1805: “the Indian woman [Sacagawea] recognized the point of a high plain to our right which she informed us was not very distant from the summer retreat of her nation on a river beyond the mountains which runs to the west. this hill she says her nation calls the beaver’s head from a conceived resemblance of it’s figure to the head of that animal.”

– By Candy Moulton –

Lewis’ journal entry, June 13, 1805: “I had proceed on this course about two miles … whin my ears were saluted with the agreeable sound of a fall of water and advancing a little further I saw the spray arrise above the plain like a collumn of smoke which soon began to make a roaring too tremendious to be mistaken for any cause short of the great falls of the Missouri.”

– Photo by Karen A. Robertson –

Clark journal entry, October 19, 1804: “In walking along the shore we counted fifty-two herds of buffalo and three elk, at a single view. Came upon the remains of one of the Mandan villages, the first ruins we have seen of that nation in ascending the Missouri.”

– By Karen A. Robertson –

–By Candy Moulton –