Kevin Jarre was capable of greatness.

Kevin Jarre was capable of greatness.

That was my first thought when I heard he had died in Santa Monica on April 3, 2011, at age 56. You can see his talent in his screenplays upon which the following films were based:

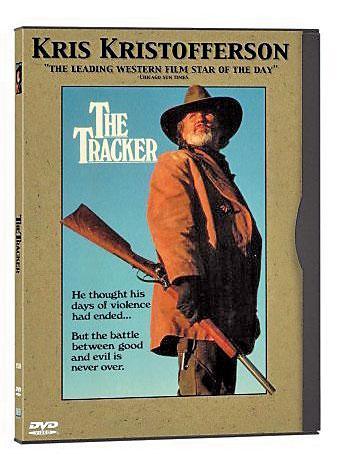

• The Tracker (1988): A terrific made-for-TV Western, starring Kris Kristofferson and Scott Wilson, in which I detected some of the lines he would later use in Tombstone.

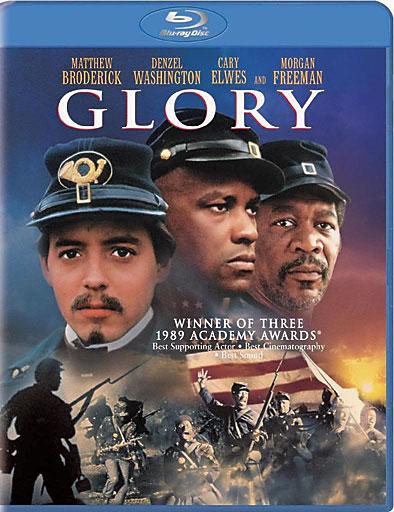

• Glory (1989): About the 54th Massachusetts regiment, this is the best movie ever made about the Civil War.

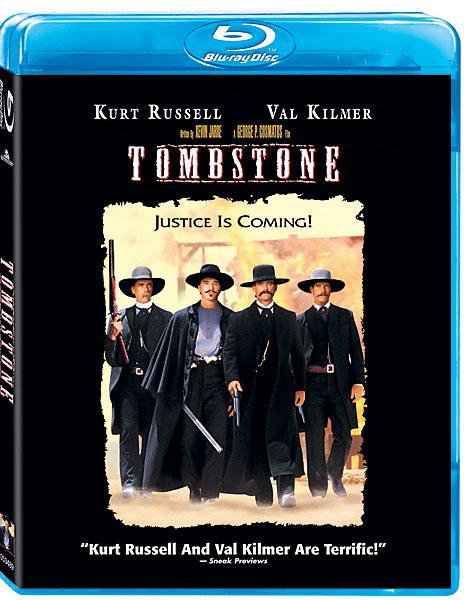

• Tombstone (1993): The most important and influential Western of the last 30 years—the pompous and self-important Clint Eastwood film Unforgiven and Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves not excepted.

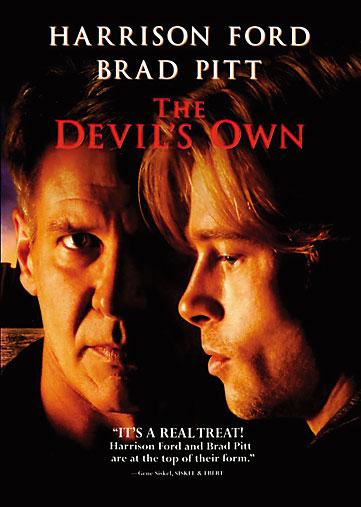

• The Devil’s Own (1997): The best screenplay I’ve ever read about the IRA and a conflicted Irish-American’s feelings about Ireland’s troubles.

Yet bitterness may have destroyed Jarre’s talent. The scripts for the last two films, in much publicized incidents, were taken out of Jarre’s hands, chopped up and hastily rewritten. On Tombstone, Jarre was also fired as director for moving too slowly.

I saw rushes for Tombstone before Jarre had been fired. Although some of Jarre’s scenes plug gaping holes that exist in the final film, he did not have much of a film sense as a director. At the pace he was going, he would have ended up with a four-to-six-hours-long miniseries, rather than a feature film.

Let me describe one of the “cut” scenes: When Wyatt Earp finds out his horse has been stolen as a prank by Billy Clanton, he rides out to retrieve it and finds himself unarmed and surrounded by the Cowboys. Wyatt says, “Look, kid, I know what it’s like. I was a kid too. Even stole a horse once.” This scenes adds a bit of Wyatt’s own personal history, and it’s the only time we see the Cowboys do what they historically did: cattle rustling.

The scene is important for yet another reason: When Wyatt asks Sherm McMasters why he’s involved with such a mob of cattle thieves, McMasters replies, “If I had to explain it, you wouldn’t understand. Just say, we’re brothers to the bone.” This “cut” line sets up Wyatt’s later question to McMasters, “Brothers to the bone, right?” after the Cowboys have shot Wyatt’s brothers Morgan and Virgil, and McMasters claims to have had nothing to do with the shooting.

For these reasons and more, Jarre’s original screenplay of Tombstone should be preserved and printed.

Jarre was shattered when he was fired from Tombstone; he pulled the pieces together only to be shattered again by Harrison Ford (at least that’s the way I heard it), who took over the production of The Devil’s Own and turned it into a good cop-bad cop action movie (the good cop, of course, was Ford).

After that, the only writing credit attributed to Jarre is for 1999’s The Mummy, but I find no trace of the Jarre I knew in that script. (Nor, for that matter, can I see anything of him in 1985’s Rambo: First Blood Part II, which he told me had almost nothing of his original screenplay left in it.)

Jarre spent the rest of his career doctoring scripts as an unaccredited contributor and earning a few assistant producer credits, which, I’m sure, gave him no satisfaction at all.

So what can we make now of his life and work? I see no sense in speculating what Jarre might have done if he had succeeded with Tombstone. His life is what it was, and his work is what it is, and the work was pretty damn good.

I hope, though, that it is not finished. Any director who shares Jarre’s vision for Tombstone can pick up that big, rich, unwieldy script and turn it into the miniseries that Jarre didn’t quite have the common sense to make it into the first time around.

Until then, as Doc Holliday says in his Latin-dueling scene with Johnny Ringo, “In pace requiescat.”

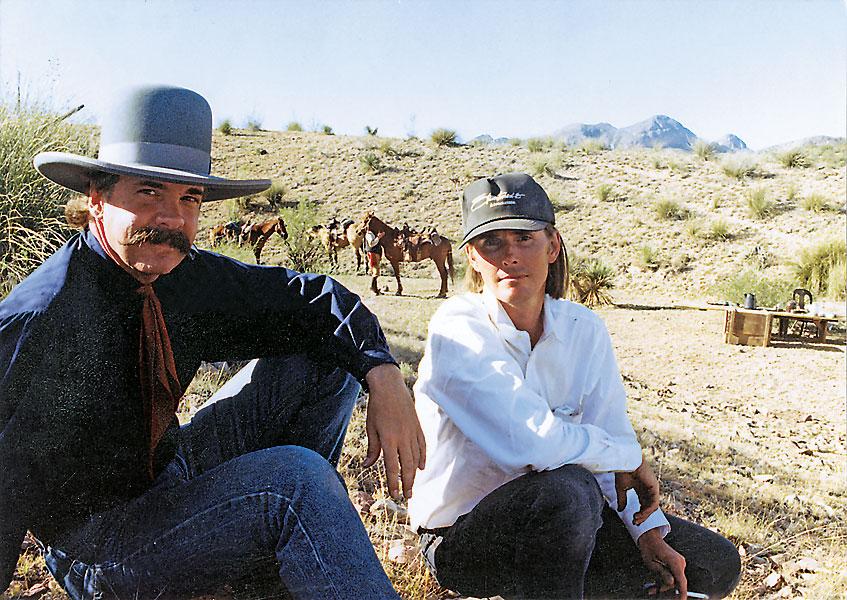

Journalist Allen Barra met Kevin Jarre on two occasions, both pleasant encounters—once on a movie set and once after a film was released.

Jeff Morey, historical consultant for Tombstone

Kevin Jarre had a lot to offer the world. Both Glory and Tombstone demonstrate his remarkable abilities. That he didn’t make more films is a loss for all of us. Working with him was one of the high points of my life.

Kevin contacted me in July 1991, because he had been told I was well informed about Wyatt Earp. We had a wide-ranging discussion about Wyatt’s life for about an hour and a half. The next day, Kevin called me to say he wanted to write a script about Tombstone and that he wanted me to be his historical consultant. Flabbergasted, I recommended he talk to some other Earp researchers before deciding on a historical advisor. But Kevin wanted me, so I agreed to work with him.

Working with Kevin was very informal. He would invite me over to his place, cook some steaks and, over some dark beer and dinner, we discussed the Tombstone story. He never had a list of questions, and he never took notes. Kevin was already familiar with the Earp literature, so he didn’t need help in getting the outline of the story straight. His questions often dealt with motives.

“Why did the men who went on Wyatt’s vendetta ride take the risk of siding with Earp?” I told him I didn’t have a ready answer for such a question. They may have been close to Morgan Earp. On the other hand, they may have been paid gunmen. As a historian, I could tell him what happened, but getting into the hearts and minds of those men was his job as a screenwriter.

“Why do you think Wyatt liked Doc Holliday?” “Because,” I replied, “Doc had once saved Earp’s life, and because Doc’s sarcasm made Wyatt laugh.”

Once, out of the clear blue, I said, “I don’t know if you are going to cover the confrontation between Doc Holliday and Johnny Ringo, but if you do, be sure to use the line from Walter Noble Burns’s book Tombstone—’I’m your huckleberry. That’s just my game.’”

Kevin worked on the Tombstone script for a full 11 months before he had a first draft completed. In June 1992, he invited me over to read it. As I read, he hovered over me like a nervous and expectant father. What I read amazed me. Those who love the 1993 movie have no idea how much better the script is than the film. It was personal, yet epic. It captured the historical period without losing a contemporary audience. And it had a remarkable driving energy. When I finished reading, I told Kevin that he had redefined the Western film.

While I supplied Kevin with a good deal of information for the film, I never could have fashioned that data into the script that he created. He had the rare power of an alchemist who could transform the harsh noise of life into pure music. We won’t see his like again.

—Jeff Morey

Photo Gallery

The Tracker (1988): A terrific made-for-TV Western, starring Kris Kristofferson and Scott Wilson, in which I detected some of the lines he would later use in Tombstone.

– By Bob Boze Bell –

– Tombstone set photo: by Bob Boze Bell –