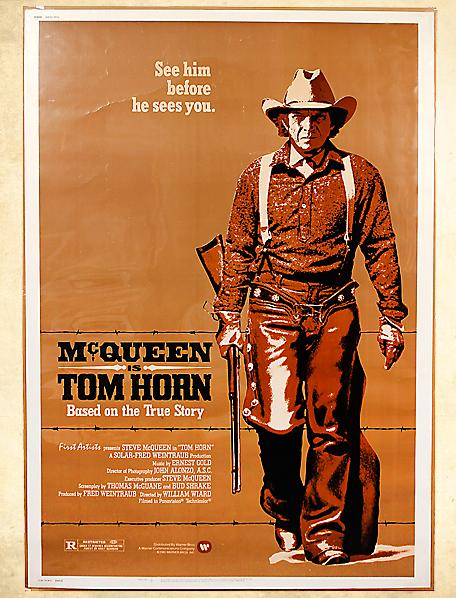

Steve McQueen and troubled productions seemed to be synonymous. Look at any one of his classic films—The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, The Sand Pebbles, Bullitt and Papillon—each riddled with turmoil. Those productions, however, paled in comparison to his last Western, the highly underrated Tom Horn.

Steve McQueen and troubled productions seemed to be synonymous. Look at any one of his classic films—The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, The Sand Pebbles, Bullitt and Papillon—each riddled with turmoil. Those productions, however, paled in comparison to his last Western, the highly underrated Tom Horn.

The project took three years to go from concept to celluloid, had its budget slashed from $10 million to $3 million, went through four directors and two producers, and experienced the painful death of McQueen’s dog Junior, who was most likely gobbled up by wolves.

To tell the story, McQueen alternated between two shooting scripts—a sweeping epic by Tom McGuane, which was twice the size of a normal screenplay, and a scaled-down version by Bud Shrake—to see his vision through.

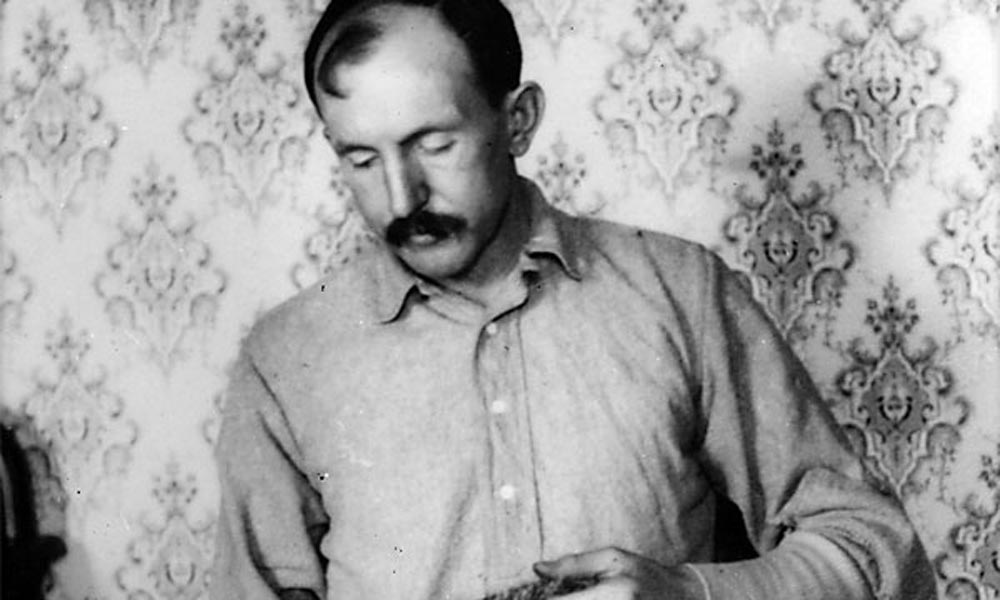

Weeks before principal photography, McQueen and Barbara Minty, his then-girlfriend who later became his third wife, visited Horn’s grave at the Old Pioneer Cemetery in Boulder, Colorado, to see if he could “pick up on Horn’s vibration.” The actor later told friends that he felt Horn’s presence and was asked by the legendary frontiersman to tell his story.

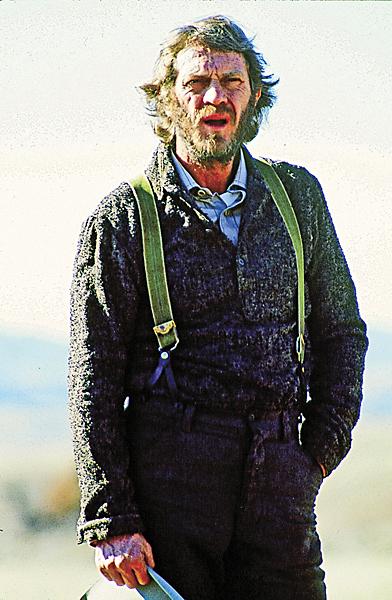

Tom Horn was a Western, but this film would not feature the sort of daring action sequences of McQueen’s early Westerns. He was, in early 1979, a middle-aged man of 48, and time had finally caught up with him. Yet those traits played to McQueen’s advantage. First, he looked the part of Tom Horn, the aging cowboy. This was an ironic marked contrast to McQueen playing a teenaged boy in Nevada Smith at the age of 35. Second, his good looks were not left to carry the film; McQueen was forced to rely on his acting, and it paid off.

“From what I witnessed, Steve wasn’t a method actor. In fact, he frowned upon that approach,” Barbara Minty McQueen says. “Instead, he started his research by reading all the material he could get his hands on. He truly believed in presenting his character as honestly as possible, never wanting to make his acting a ‘Hollywood’ caricature or superhero. Realism was his driving force.”

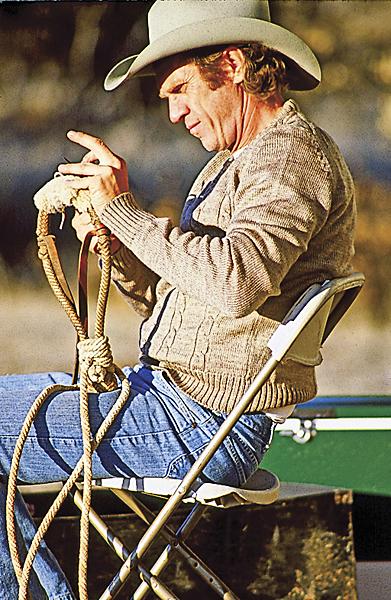

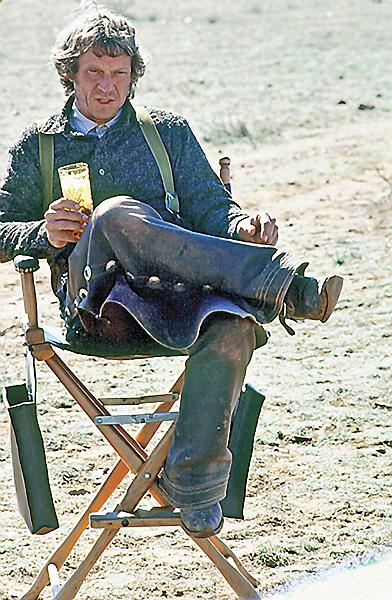

McQueen’s dedication couldn’t be denied. In addition to living on the set in a Winnebago on the plains of Nogales, Arizona, a few minutes from the Mexico border, for three months, McQueen served as the unofficial director, continually working on the script and going over his lines every night.

“Before we started shooting, Steve was running around in everybody’s business. ‘Put that light there. Was it there last time?’ But it was all to make the shot better,” costar Geoffrey Lewis recalled. “When they called for action, my back was to him, but when I turned around, I got the full force of Steve McQueen right in my face. He almost knocked me down. It was like a whack in the face. Those blue eyes…. It was pretty intense.”

Tom Horn was completed in March 1979, and the initial reviews when the movie was released a year later were a mirror reflection of the box-office take—a mere $12 million. One critic summed it up best: “Tom Horn suffered from public antipathy toward the genre. In an earlier decade, this lyrical, deeply felt little film would have been hailed as a classic.”

More than three decades after its release, the movie has gained respect because, in many ways, Tom Horn and McQueen’s performance were ahead of their time. Audiences were used to action-packed Westerns with gunfights and brawls. McQueen offered them something different—a meditation of the West and a character study of one of America’s best-known figures of the era.

“Tom Horn, I thought, was Steve’s best movie,” says James Coburn, who costarred with McQueen in three films. “He was loose and free, and he wasn’t guarded. Most of his films he was guarded. He had a form. If the film wasn’t rigid enough, he was going to be good. I always felt Steve would really be a good actor if he ever grew up…. I think he finally did on Tom Horn. That was him finding his adulthood.”

Photo Gallery

– All set photos by Barbara Minty McQueen –