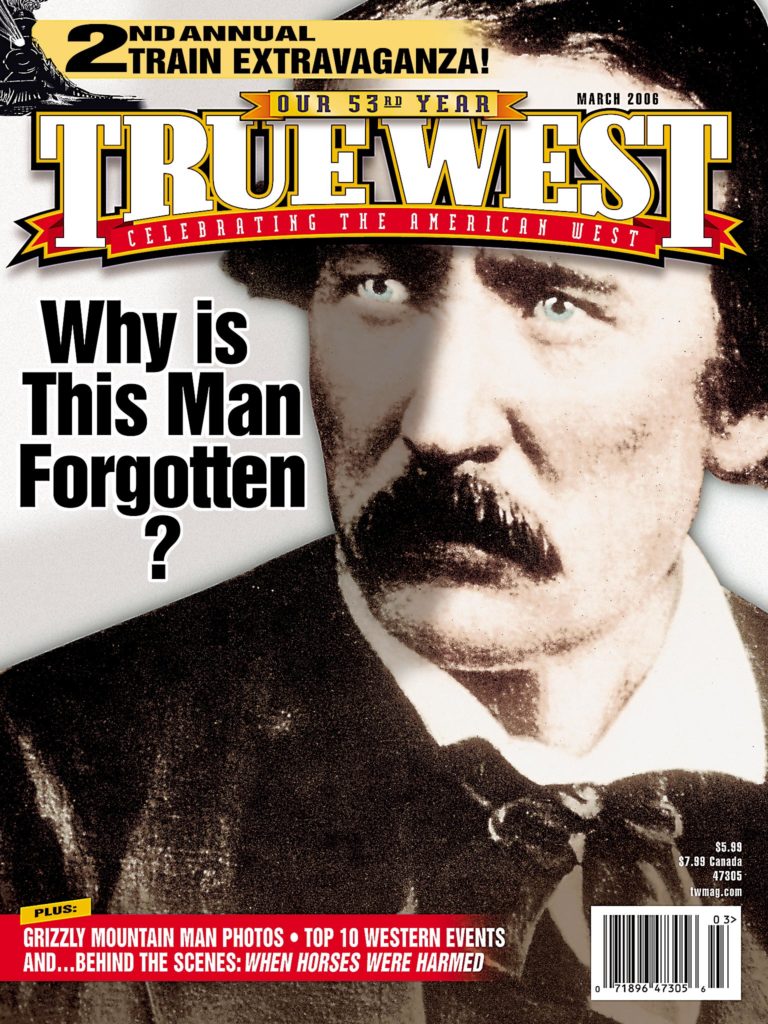

She was one of the guiding lights of Arizona literature, the territory’s first female office holder and she helped cinch Arizona’s statehood.

She was one of the guiding lights of Arizona literature, the territory’s first female office holder and she helped cinch Arizona’s statehood.

But today, most know her only because of the historical museum in Prescott, Arizona, that bears her name. Sharlot Hall was a woman of the 19th century who would have been far more at home—and far less distressed—during the women’s liberation days of the 20th century.

Her life is important, not only for the beautiful poems and insightful journalism she left behind, but also for her struggle against a domineering, anti-intellectual father and a society that saw women as far less important than men.

As former Arizona Gov. and Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt has written, “As Sharlot Hall grew to womanhood and literary skill, she also confronted a nineteenth-century society that mirrored the prejudices of her father. A woman seeking intellectual freedom and achievement threatened a social order which expected women to be subservient and submissive. For many women the high price of freedom was forsaking marriage, children and polite society, and assuming instead the less threatening role of eccentric outcast. Sharlot Hall followed that pattern.”

It is not an accident that her 1982 biography by historian Margaret F. Maxwell is titled A Passion for Freedom.

An Early Lesson

Sharlot was born in Kansas on October 28, 1870, and migrated to Arizona Territory with her family just as she was turning 12.

She had been writing songs and poems since she’d learned to read. Six years after arriving in Arizona, her first article was published in a regional magazine, Land of Sunshine, headquartered in Los Angeles.

When the magazine changed its name to Out West in 1902, the editor asked Sharlot to write a poem to honor the new title—it became so popular, it was set to music and became required reading for students.

She became an editor for Out West and lived in Los Angeles for a time, but her articles mostly sang the virtues of Arizona. She’s credited with helping “interpret the Southwest” to those back East.

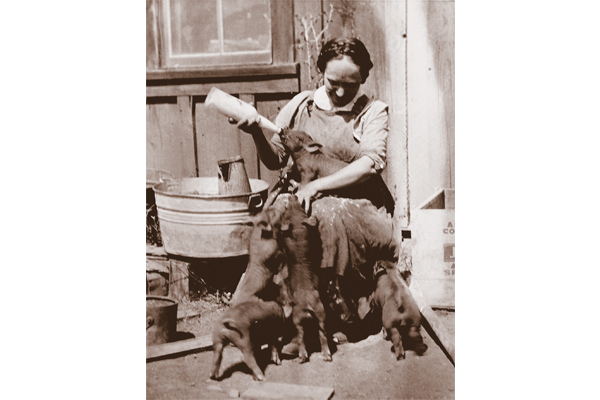

But her greatest contribution was her respect for the heritage of the frontier. As her biographer put it, “A pioneer in recognizing the need to record the ways of earlier generations, she collected Arizona artifacts, early documents and oral histories. She tracked down pioneer Arizona miners, cattlemen, sheepherders, and prospectors, no matter how many miles she had to drive, alone or with a guide, over roads that were often only dim trails in the desert.”

Changing History

Sharlot’s most famous poem—the one that perhaps changed history—is titled “Arizona.” She wrote it in 1906 when President Theodore Roosevelt endorsed a Congressional proposal to grant statehood to a merged Arizona and New Mexico. History tells us Arizona was too Democratic and New Mexico was too Catholic and Mexican for the tastes of Republican Protestants in Washington. Her poem was defiant:

No beggar she in the mighty hall where her bay-crowned sisters wait;

No empty-handed pleader for the right of a freeborn state;

No child, with a child’s insistence, demanding a gilded toy;

But a fair-browed, queenly woman, strong to create or destroy….

By the end of its eight stanzas, any reader felt Arizona’s scornful indignation. The state was delighted with the voice she gave to their hearts. Dwight Heard, then publisher of The Arizona Republican, printed the entire poem on his editorial page. The paper even paid to have the poem reprinted. Territorial Gov. Joseph Kibbey had copies placed on the desks of every single member of Congress, where it was read into the Congressional Record.

Meanwhile, Out West Magazine devoted almost an entire issue to Arizona, which included Sharlot’s poem and her exhausting travelogue of Arizona’s virtues.

Did her poem and articles turn the tide? Congress did reconsider and allowed the two territories to vote on merging—New Mexico said yes; Arizona said a resounding no. And on Valentine’s Day of 1912, Arizona became the 48th State.

At least one journalist thought Sharlot deserved credit for defeating the joint statehood idea. The editor of the Morning Courier in Du Bois, Pennsylvania, wrote, “The people of Arizona … should not fail to give credit in their jubilation to Sharlot M. Hall…. (She) perhaps put out the strongest papers that were issued to show why Arizona should, when admitted to statehood, be admitted as a great commonwealth singly.”

First Woman Honors

By the time Arizona became a state, Sharlot had made history again. She left Out West in 1909, when she was appointed territorial historian—making her the first woman to hold public office in Arizona. But it took a public fight to give the job to a woman.

Originally, the newly-created state office didn’t go to Republican Sharlot but to Democrat and former newspaper man Mulford Winsor. Members of the Phoenix Women’s Club were so outraged, they filed an official protest, noting Sharlot Hall wouldn’t have to start from scratch in chronicling frontier history, as Mr. Winsor would have to do, because she’d already been at it for over 15 years.

Governor Kibbey went so far as to publicly admit he was politically blackmailed into Winsor’s appointment, explaining the legislature would never have created the position if Sharlot were to get it.

As political winds changed and Arizona got a new governor, Sharlot got her position as territorial historian. While some applauded—her unique position made her a cause celebre in the U.S.—the legislature was so incensed at the idea of a woman holding the job of territorial historian that legislators tried to insert a plank in the constitution that would have barred women from holding public office. (It is one of history’s delicious ironies that exactly 90 years later, Arizona would become the first and only state to have women in its top five elected offices, from governor on down.)

Sharlot held the historian job until the year of statehood in 1912, when she went home to care for her aging parents. Her mother died later that year. She found herself trapped with her father and spent the next 12 years, until her father’s death, in a world she’d worked her whole life to avoid.

A Dress of Copper

In January 1924, Sharlot was chosen to hand deliver Arizona’s presidential votes for Calvin Coolidge to Washington. In honor of the occasion, Arizona’s mining companies fashioned a copper mesh dress for her to wear at Capital festivities. (She completed the outfit by wearing a hat decorated with cactus.)

In 1927, Sharlot began to fulfill the dream that has become Sharlot Hall Museum. The Old Governor’s Mansion, which had sat empty for years, was bought by the city of Prescott and leased to Sharlot for life. She moved in and spent the last 16 years of her life—using her own money or donated funds—to restore the home as a museum of territorial history.

Sharlot Hall died on April 9, 1943, in Prescott at the age of 72. But her legacy lives on in one of Arizona’s popular tourist attractions.