He was disgusted with what American society had made him into — what they expected of him — and he hated even more failing to live up to those expectations.

He was disgusted with what American society had made him into — what they expected of him — and he hated even more failing to live up to those expectations.

On October 24, 1849, just east of Point of Rocks on the Santa Fe Trail, Jicarilla Apaches ambushed the party of Missouri merchant James White, slaughtering all six men as well as a black female servant, and carrying off the merchant’s young wife Anna and infant daughter Virginia.

Pueblo Indians, passing through the Apache camp soon afterward, reported to authorities in Santa Fe that the white woman and her child were still with the Jicarillas. Major William Grier, determined to rescue them, needed the help of America’s most famous frontiersman—Kit Carson.

He quickly led them to the massacre site, still littered with looted baggage and broken wagons, and then down the Canadian River, following the Apache campsites. In every abandoned camp, he found a strip of calico or the torn page of a book, making him all the more determined to save this brave woman. “It was the most difficult trail that I ever followed,” Carson later recalled.

Carson and his fellow scouts found fresh signs of the Jicarillas on November 15, following their trail away from the river. Two days later, they found the camp. Grier suddenly halted them within 100 yards of the village to allow the howitzers to catch up. Carson was livid, demanding that they attack at once before the Apaches could escape.

As Grier argued with Carson, an Apache bullet knocked him from his saddle. Carson, not pausing for a moment, led the troops down upon the Apache encampment. Most of the Indians, under cover of the fake parley, had escaped beyond the river on their fresh horses. The soldiers counted six dead Apaches among the 30 Indian lodges. They captured all the Apache provisions, some 70 ponies, as well as recovered the goods stolen from the merchant’s wagon train.

Not far from the Apache lodges, Carson found the body of Anna White. She was, Carson noted, “perfectly warm, had not been killed more than five minutes—shot through the heart with an arrow.”

Carson blamed Grier for the woman’s death, noting that “I am certain that if the Indians had been charged immediately on our arrival, she would have been saved.”

Although Carson eventually forgave Grier, he never really forgave himself for Anna’s death. In the abandoned camp, among her baggage, was found a copy of Charles Averill’s Kit Carson, the Prince of the Gold Hunters. This was perhaps the first of many Kit Carson novels, and it horrified Carson when parts were read to him (he could not read): “I was made a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundred, and I have often thought that as Mrs. White would read the same, and knowing that I lived near, she would pray for my appearance and that she would be saved. I did come, but had not the power to convince those that were in command over me to pursue my plan for her rescue.”

Kit Carson had met his legend head on—but with tragic consequences. He urged his companions to throw the book into the campfire, for the mantle of America’s greatest frontiersman, inherited by him from Boone and Crockett, had become heavy indeed.

Fame haunted Carson throughout his life, but even more after his death. His accomplishments were many, and it is no exaggeration to state that of the grand quartet of frontiersmen who defined the Western movement—Boone, Crockett, Carson and Cody—Carson’s remarkable adventures and impressive contributions to history place him at the top of the list. Yet, a little over a century after his death, he is all but forgotten by most Americans, and when recalled at all is often disparaged as a genocidal villain. Fame has indeed played a bizarre trick on the reputation of Kit Carson.

A Young Kit Carson

Christopher Carson is born to Rebecca and Lindsey Carson on Christmas Eve 1809 in Madison County, Kentucky. Lindsey Carson moves his large family westward in 1811, settling at Boon’s Lick in Howard County, Missouri. The boy, the eleventh of 15 children, is shattered by his father’s tragic death in 1818. The old man was killed while clearing trees. Rebecca, unable to handle the boy, apprentices him to a saddler, David Workman, in Old Franklin three years later. The boy runs away to join a Santa Fe-bound wagon train in 1826, which leads to his first appearance in the press: “Notice is hereby given to all persons, that Christopher Carson, a boy of about fourteen years old, small of his age, but thick set, light hair, ran away from the subscriber … to whom he had been bound to learn the saddlers trade, on or about the first of September last. One cent reward will be given to a person who will bring back the said boy.”

By 1831, Carson is a full-fledged Mountain Man. Joining a band of trappers headed by Thomas “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick, he heads north to winter on the Salmon river in Idaho and traps beaver throughout the Rockies. This hard, dangerous work includes numerous sharp fights with the northern tribes who view the trappers as trespassers and economic rivals, but Carson revels in it. These years form his character and outlook, and he will later recall his youthful days in the mountains as the happiest time of his life.

In August 1835, Carson attends the great Rendezvous on the Green River in western Wyoming. It is a wild gathering, full of drinking, gambling, sharp business deals and brawls. And it’s the beginning of the grand legend of Kit Carson.

He participates in a dance at a nearby Arapaho encampment, where he is smitten with a young girl, Waanibe or Singing Grass. A rival for her affections is a French Canadian giant working for the American Fur Company—Joseph Chouinard, nicknamed the “Great Bully of the Mountains.” The jealous Frenchman, angry over Waanibe’s attention to Carson at the dance, abuses the girl. Carson, all of five-foot-six and weighing but 150 pounds, seeks out the Frenchman and challenges him to a duel. The missionary Samuel Parker, on his way to convert the Oregon Indians, sees the fight: “The great bully of the mountains mounted his horse with a loaded rifle and challenged any Frenchman, American, Spaniard, or Dutchman to fight him in a single combat. Kit Carson, an American, told him if he wished to die he would accept the challenge. Shunnar [sic] defied him—Carson mounted his horse and with a loaded pistol rushed into close contact, and both almost at the same instant fired.” Carson seriously wounds the bully, who then begs for his life. (It is not known if Kit’s rival lived, but neither Carson nor Parker mentions his death.)

When Reverend Parker publishes his Western adventures in 1838, it is the first mention of Kit Carson in a book. By that time, Carson has married Waanibe. Together, they trap the Three Forks of the Missouri with Jim Bridger, all the while repeatedly battling the Blackfeet. When Waanibe bears him a daughter, who they name Adeline, Carson heads south to safer country, hiring on as a contract hunter at Fort Davy Crockett in Brown’s Hole in northwestern Colorado. There, Waanibe bears him another daughter but dies soon after from complications related to childbirth. Carson’s world is destroyed, and his days in the mountains are over.

Guiding Fremont

In 1840, after a decade in the mountains, Carson takes a job as a hunter at Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River in southeastern Colorado. With two infant daughters to care for, Carson looks about for a new wife and finds a likely young woman among the Cheyennes camped near the fort. But Making Out Road soon divorces him Cheyenne style, by tossing all his goods outside the tipi. Not long afterward, tragedy strikes when Carson’s youngest daughter falls into a pot of boiling water and is scalded to death. Determined to make a better life for his other daughter Adeline, Carson takes her to St. Louis in 1842 so that she may be educated at a Catholic school. After visiting with relatives, he rides a steamer back up the Missouri and there meets young Lt. John Charles Fremont.

Fremont, in search of a guide for an expedition to South Pass, has now found his man. This meeting will be the turning point of Carson’s life and the beginning of a grand collaboration and deep friendship that will change forever the lives of both men as well as the destiny of the American West.

Carson guides Fremont to South Pass in the summer of 1842 and then serves as scout and hunter for a second expedition to California the next year. Fremont, impetuous, handsome and ambitious but not terribly bright, has the good fortune to be married to the beautiful and brilliant Jessie Benton, daughter of the powerful Missouri Sen. Thomas Hart Benton. The senator has 10,000 copies of Fremont’s two reports, each ghostwritten by Jessie, printed at government expense. The books make Fremont and his intrepid guide, Kit Carson, into national heroes.

The second expedition, far more ambitious than the first, circuits almost the entire West. Carson and Fremont carefully explore the Great Salt Lake and give a name to the Great Basin before heading west to Oregon. They cross the Sierra Nevada in midwinter to reach Sutter’s Fort on the Sacramento River and eventually traverse almost all of Mexican-owned California from north to south before turning eastward on the Old Spanish Trail and following it north into Utah to explore Utah Lake and the Wasatch and Uinta Mountains. They cross the Rockies to arrive at Bent’s Fort on July 2, 1844, where Bent holds a feast in their honor on July 4. It would later be truthfully written of Fremont that upon the ashes of his campfires arose the great cities of the American West.

Fremont, however, was not a conventional explorer like Lewis and Clark or Stephen Long, but rather a booster and promoter who saw in the great unsettled West the future of the republic. His reports, while useful as guidebooks for the thousands of settlers who later used them, are also romantic narratives of grand adventure—with Kit Carson at their center.

In August 1845, Fremont sends word to Taos that he needs Carson for a third expedition. Carson is hesitant to go, for he is now a married man with children. On February 6, 1843, he had married Josepha Jaramillo in Taos. She is from a prominent New Mexico family that, while not wealthy, is well connected. Her sister is married to Charles Bent. Josepha is but 15 at the time of her wedding, while the groom is 33. She is a rare beauty who impresses all who meet her with her graceful refinement. Lewis Garrard falls under her spell while visiting Taos: “Her style of beauty was of the haughty, heart-breaking kind—such as would lead a man with the glance of the eye, to risk his life for a smile.” She will bear Kit eight children.

Carson reluctantly joins Fremont at Bent’s Fort in late August. Fremont’s orders are to explore mountain passages over the Sierras into Mexican California, but they are merely a cover. His 60 heavily armed men are the agents of Manifest Destiny with California as their prize. War clouds are already gathering on the Rio Grande as the explorers lead their rugged band into Sutter’s Fort on January 15, 1846. Their pivotal roles in the Bear Flag revolt and the American conquest of California further enhances their heroic reputations back East. Carson’s daring mission through enemy lines to seek help for Gen. Stephen Kearny’s besieged troops at San Pascual (present-day San Diego County) in December 1846 makes him an official war hero.

The new military officers in California are all anxious to meet the famous Kit Carson, and none more so than a young lieutenant of artillery, William Tecumseh Sherman. “His fame was then at its height, from the publication of Fremont’s books,” Sherman wrote, “and I was very anxious to see a man who had achieved such feats of daring amongst the wild animals of the Rocky Mountains, and still wilder Indians of the Plains. I cannot express my surprise at beholding a small, stoop-shouldered man, with reddish hair, freckled face, soft blue eyes, and nothing to indicate extraordinary courage or daring.”

While in California, Carson is often employed as a dispatch rider carrying vital messages to Washington D.C., including the news of the discovery of gold in May 1848. In the capital, he stays at Sen. Benton’s home, where he retreats before a legion of society ladies who flock there to meet him. Jessie Fremont discovers that Carson is concerned that if the society folk discover he had once been married to Waanibe, they would be highly offended by his company. Jessie, though, is inspired by his continued loyalty: “He had been afraid the ladies might not care to have him there if they knew he had married a Sioux [sic] wife. ‘But she was a good woman,’ he declared. ‘I never came in from hunting but she had warm water for my feet.’ I have always remembered that—it was so like the simplicity of the Bible.”

Carson’s 1858 appointment as the Indian agent for the Utes brings him back into government service. Despite his inability to read or write, he has command of several native dialects as well as perfect fluency in Spanish. He hires a clerk to write his reports with the funds normally reserved for an interpreter. He proves a most effective agent. Years later, Sherman, then a lieutenant general, visits Carson. “His integrity is simply perfect,” he tells a fellow officer. “The red skins know it, and would trust Kit any day before they would us, or the President either!”

During his time as agent, Carson pays the ransom for a three-year-old Navajo boy held by the Utes. A Ute chief told Josepha that the boy was too much trouble and that they intended to kill him. She offers a horse for the child and brings him into her house. He is formally adopted by Kit and baptized as Juan Carson. The child grows to young manhood and marries a New Mexican girl, but he dies soon after. The other Carson children always considered him a brother.

A remarkably devoted family man, Carson laments how his loyalty to his government keeps him from his loved ones. Dr. D.C. Peters, who knows him well, calls Carson “a man of singularly striking virtues, for one who led such a rough kind of life. His gentleness of heart was shown in his love for his friends, and in his domestic inclination, for over and above all desire for adventure, he loved home.”

Carson’s real involvement in the “Long Walk”

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Carson resigns as Indian agent to accept a commission as lieutenant colonel of the First New Mexico Volunteers. Promoted to colonel in September, Carson takes an active role in Gen. Edward Canby’s inept defense of New Mexico against the invading Texans under Gen. H.H. Sibley. Although he fights in the Battle of Valverde in February 1862, Carson misses the eventual Union victory over the rebels at Glorieta Pass that March. With the Confederates defeated, the new Union commander in the Southwest, Gen. James H. Carlton, turns his attention to the Navajos and Apaches who have increased their raids on the New Mexican settlements during the rebel invasion. Carlton enlists his old friend Kit Carson for this grim duty.

Carson balks at the assignment, arguing that he joined the army to fight rebels, not subjugate Indians. Yet Carlton prevails, and Carson is soon at Fort Stanton on the Rio Bonito with five companies of New Mexico volunteers. His written orders to march against the Mescaleros are simple and brutal: “All Indian men of that tribe are to be killed whenever and wherever you find them. The women and children will not be harmed, but you will take them prisoners, and feed them at Fort Stanton.” Carlton’s plan is to confine the Mescaleros at a new fort he is building on the Pecos at Bosque Redondo. After several sharp engagements, the Mescaleros come to Fort Stanton to seek Carson’s protection. Disobeying his no quarter orders, Carson feeds and protects them. In November, he provides a military escort for Chief Cadete and four other Mescalero leaders who travel to Santa Fe for a meeting with Carlton. By March 1863, over 400 Mescaleros have relocated to Fort Sumner, and the campaign is over.

Carlton then turns to the uncowed Navajos. In June, Carson marches westward with over 700 men, including Ute, Hopi and Zuni warriors. They have many old scores to settle with the Navajos, who have raided their Indian, Mexican and Anglo neighbors with impunity for generations. Now they will reap the whirlwind.

The Navajos call Carson “Red Shirt” at first, on account of his clothing, but later refer to him as “Rope Thrower” because he lassos so many of them. He pursues them relentlessly, even deep into their stronghold at Arizona’s Canyon de Chelly, but they abandon their villages. Carson responds by burning their lodges, belongings and crops. Winter is his ally as starvation, insecurity and exposure take a relentless toll on the Indians. It is a military campaign with few battles and hardly any casualties on either side—yet it is an amazing success. A few Navajos straggle into Fort Canby to surrender to Carson. His kind treatment of the captives leads hundreds and then thousands more to come in. By January 1864, over 8,000 Navajos have surrendered.

Carson has killed only 23 Navajos in his Canyon de Chelly campaign, but he is still delighted with the results, which he reports to Carlton: “We have shown the Indians that in no place, however formidable or inaccessible, are they safe from pursuit of the troops of this command. And have convinced a large portion of them that the intentions of the Government toward them are eminently humane … that the principle is not to destroy but to save them, if they wish to be saved.”

Carson’s report reveals his realization that the Navajos are divided between the wealthy chiefs, or ricos, and poor ladrones, who commit most of the raids, but that the ricos suffer greatly from New Mexican retaliatory raids since they’re less mobile and have more property to lose. The brunt of Carson’s campaign now falls on them as well, for the innocent suffer far more than the guilty in this war.

Much of Carson’s time in the early Spring of 1864 is spent protecting his Navajo prisoners at Fort Canby from marauding New Mexicans who come to kill and rob them. As his prisoners march eastward to the Bosque Redondo, Carson warns Carlton to properly care for them: “It is while here, and en route that we must convince them by our treatment of them of the kind intentions of the Government towards them, otherwise I fear that they will lose confidence in our promises, and desert also.”

Carlton ignores Carson, and the ordeal of the so-called “Long Walk” to Bosque Redondo quickly evolves into a shameful catastrophe. Rations and transportation are limited; the weather turns brutal as do the New Mexicans who regularly assault the prisoners. At Bosque Redondo, it is no better. The Mescaleros are hostile to the newcomers, Comanches raid from the east, the rations are short and disease of every sort epidemic. The death rate is appalling. Four years later, an embarrassed government rejects Carlton’s reservation plan and returns the natives to their homeland. For the Navajo people, the Long Walk and Bosque Redondo are the turning point of their history, and they lay the blame for this squarely on Kit Carson.

Carson, however, takes no part in the Long Walk, returning home to his family in April 1864. Carlton briefly assigns him to Fort Sumner, but after a disgusted Carson submits his resignation for a third time, the flinty general relents and orders him out against the Comanches on the Staked Plain.

In early November, Carson leads over 300 soldiers, with two howitzers and 75 Ute and Apache allies, eastward to the old trading post at Adobe Walls. There, he battles over 1,000 Comanches and Kiowas on November 24 in a desperate fight that foreshadows the Great Plains wars to come. Carson knows that he and his men are lucky to have survived the battle with few casualties, saved by their savvy Indian allies and the firepower of their howitzers.

“This brilliant affair adds another green leaf to the laurel wreath which you have so nobly won in the service of your country,” gushes Gen. Carlton. Carson probably does not know what a laurel wreath is, but he certainly appreciates the brevet as brigadier general of volunteers that he receives from President Lincoln in March 1865.

Mourning a Hero

When Carson is placed in command of Fort Garland, Colorado, Gen. Sherman visits him in 1866. “Carson then had his family with him,” Sherman later recalled, “his wife and half a dozen children, boys and girls as wild and untrained as a brood of Mexican mustangs.” Sherman finds Carson quite melancholy over his children. He worries about their future since he has few financial resources and his health is rapidly failing. “I fear I have not done right by my children,” he broods. In time, Sherman takes Kit’s son William as a ward and pays for his education.

Carson’s concern over his health is well founded. A fall from a horse in 1860 caused internal damage that never healed and by 1866, he is in great pain from an aneurism. In the spring of 1868, he returns from an arduous trip to Washington (where he took a delegation of Utes), anxious to be with Josepha who is about to give birth. Their daughter Josefita is born on May 13, but within a few days, Josepha becomes ill and dies. The devastated Carson is taken by wagon to Fort Lyon, Colorado, where Dr. H.R. Tilton tends to him. He refuses to sleep on a bed, preferring to recline on a buffalo robe spread on the floor of the doctor’s cabin. His will to live gone, Carson dies quickly on May 25, 1868, when the aneurism bursts—“Doctor, compadre, adios,” being his last words.

General Sherman mourns him but also realizes that the West of Carson has passed. “Kit Carson was a good type of a class of men most useful in their day,” notes the unsentimental general, “but now as antiquated as Jason of the Golden Fleece, Ulysses of Troy, the Chevalier La Salle of the Lakes, Daniel Boone of Kentucky … all belonging to the dead past.”

A more romantic view is expressed by Jessie Fremont. “Kit Carson was a man among men, a type of the real American pioneer, not only fearless but clear headed, as gentle as he was strong,” she muses. “All who knew Carson best, when they hear him spoken of, will not think of him only as the brave man, or the great hunter, or the cool, sagacious, admirable guide, but first and tenderly as their ‘Dear Old Kit.’”

Pulp Indian Killer

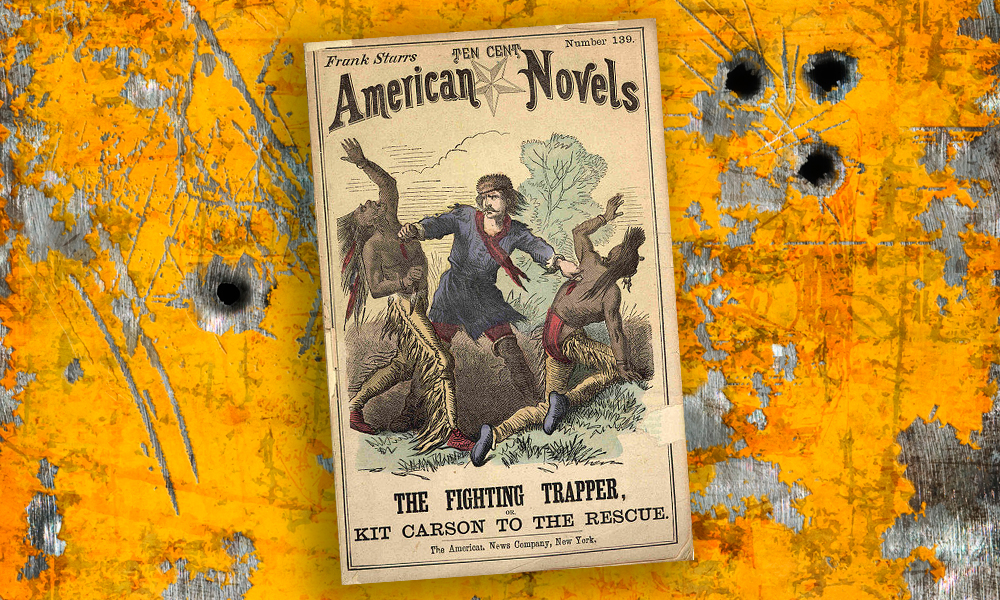

Carson’s death coincided with the introduction of the pulp dime novel in America, and he quickly became fodder for these blood-and-thunder tales.

At least 70 fanciful stories feature Carson between 1860 and 1900, and in most, he is celebrated as a great Indian killer. This theme is repeated in American comic books in the early 1950s as well as in a series of British adventure annuals that run from 1954-60. Nineteenth-century hagiographic biographies by Buffalo Bill Cody, Edward Ellis and John Abbott help to cement Carson’s reputation as the greatest of the mountain men, as does the 20th-century romantic biographies by Edwin Sabin, Emerson Hough, Bernice Blackwelder, M. Marion Estergreen and, most important, Stanley Vestal.

At first, it seems as if Carson’s legend will prove equally popular with the new filmmakers as several silent films—most notably The Covered Wagon with Guy Oliver in 1923 and Kit Carson with Fred Thompson in 1928—feature him. The sound era, however, relegates Carson to “poverty row,” where his story is told in serials such as Fighting with Kit Carson (1933) starring Johnny Mack Brown, The Painted Stallion (1937) with young Sammy McKim and Overland With Kit Carson (1940) with Bill Elliott. A well-budgeted, 1940 Edward Small production, titled Kit Carson, stars Jon Hall as Carson and Dana Andrews as Fremont, but it makes a slight impression. Compare the few Carson films with the stunning Hollywood output on Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp and George A. Custer, and it becomes clear why Carson begins to fade from the public’s consciousness.

Television might have brought Carson back into the limelight, as it did for Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone and Wyatt Earp, but the 104 episodes of The Adventures of Kit Carson syndicated from 1951-55 are kiddie fare, far removed from historical reality or serious drama. Bill Williams as Carson, along with his sidekick El Toro played by Don Diamond (later featured in the Zorro series), roam the West, administering justice much like the Lone Ranger and Tonto. Walt Disney Presents features two episodes of Kit Carson and the Mountain Men in January 1977, but the show fails to find an audience. David Nevin’s 1983 bestseller Dream West is made into a 1986 TV miniseries starring Richard Chamberlain as Fremont and Rip Torn as a crusty Carson, but it also fails to generate much interest.

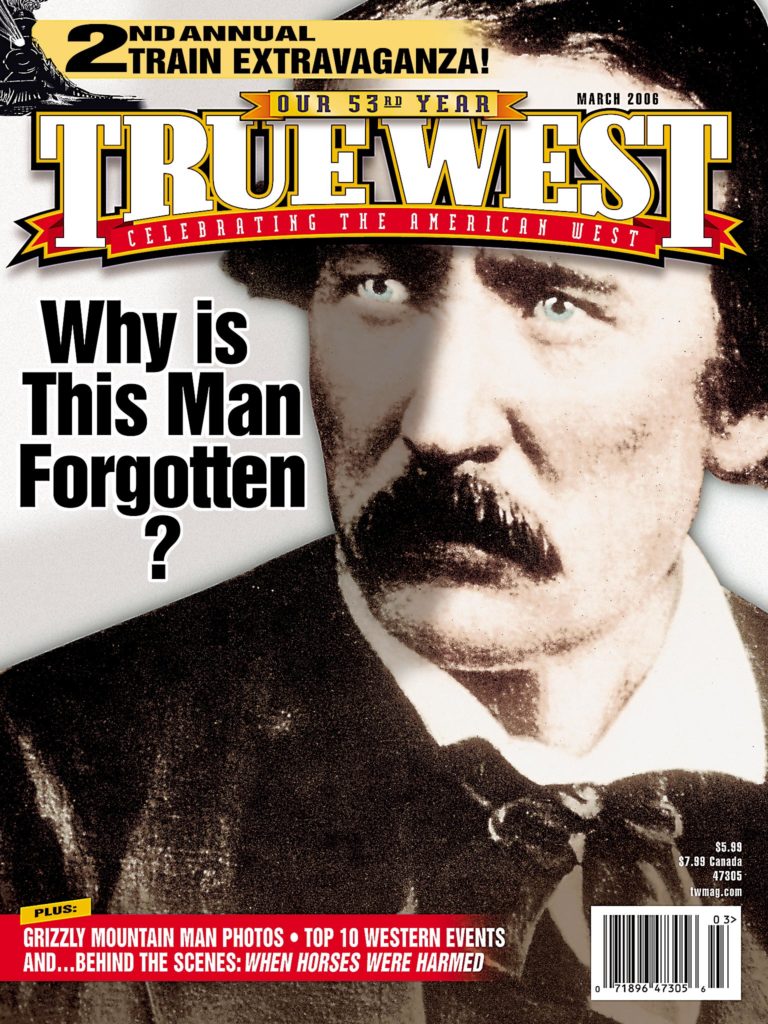

Why is This Man Forgotten?

Despite the media failure to exploit Carson’s life with a great story, he nevertheless remains ubiquitous throughout the West. The state capital of Nevada, several counties, a national forest, a mountain peak, parks, an important Colorado military installation, hotels, motels, restaurants and streets in various cities are all named for him. He is honored with monuments in Denver and Trinidad, Colorado, as well as Santa Fe, New Mexico. Why then, has his reputation failed to retain its once lofty position in the American mind?

National memory is indeed fickle. That Carson’s story has never found a powerful literary, cinematic or TV storyteller has certainly contributed to the fading of his reputation. Dime novelists and earlier biographers who built him up as an “Indian killer” did not help his image when the nation’s viewpoint on the plight of the Indians became far more sympathetic.

The most important factor, however, in Carson’s fading heroic status has been the failure of his adopted home of New Mexico to celebrate him. Kentucky embraces the story of Daniel Boone with state-supported enthusiasm and state-tourism dollars, as do both Tennessee and Texas with Davy Crockett. William F. Cody has a world-class museum in the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in his Wyoming namesake town to celebrate his career, as well as an impressive grave site and museum on Lookout Mountain above Denver, both keeping his flame lit. New Mexico, however, while anxious to exploit the outlaw saga of Billy the Kid, officially shies away from Kit Carson.

In recent times, there has been a literary assault upon Kit Carson’s heroic credentials fueled by Lynn Bailey’s The Long Walk (1964), Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1969) and Clifford Trafzer’s The Kit Carson Campaign (1982). These books, building upon a Navajo oral tradition vividly expressed in Navajo Stories of the Long Walk (1973), have pilloried Kit Carson as the villain of the Navajo War. They have been remarkably successful in disgracing Carson in New Mexico and trashing his reputation nationwide.

So successful has been this revisionist assault on Carson that folks in Church Rock, New Mexico, felt justified in vandalizing the nearby Kit Carson Cave in 1979. In August 1990, some enlightened Taos citizens spray painted Nazi swastikas and the word “Nazi” on the gravestones of Kit and Josepha Carson in the Taos cemetery.

Noted Taos resident and celebrated novelist John Nichols had paved the way for such acts by his casual comparisons of Carson to Hitler and Eichman. Harry Walters, director of the museum at the Navajo Community College, declared in 1993 that defending Carson “is like trying to rehabilitate Adolf Hitler.” Arizona State University Professor Peter Iverson, in his 2002 history of the Navajos, criticized scholars like Tom Dunlay who dared to present a reasoned defense of Carson. Such sentiments were repeated on the floor of the New Mexico state legislature in 2002 by Sen. Leonard Tsosie, who effectively blocked state monument designation for the Kit Carson Museum in Taos by comparing the frontiersman to the Yugoslav president and mass murderer, Slobodan Milosevic.

Nichols and Tsosie not only disregarded the reality of history by their statements, but they also trivialized the victims of true genocide. The 23 Navajos Carson reported slain in Canyon de Chelly hardly amount to genocide. Even the hundreds of deaths encountered on the Long Walk and at Bosque Redondo, which Carson had nothing to do with, fail to compare to the incredible slaughter then routinely occurring on Civil War battlefields far to the East. American soldiers killed in 1863 at Gettysburg far exceeded the entire population of the Navajo Nation in 1864. Numbers are a false measurement of suffering, but they can provide some context in history. And in this case, they certainly should discredit the misnomer of genocide that many have applied to Carson’s campaign.

Carson was not interested in killing Navajos but rather was determined, in his own ethnocentric way, to save them. “It is of the utmost importance and should never be lost sight of, that every promise however trifling should be religiously kept,” he lectured the federal government. “In this way I am confident that in a very few years they [the Navajos] would equal if not excel our industrious Pueblos, and become a source of wealth to the Territory instead of being as heretofore its dread.”

Carson knew that the Navajos must be turned from the warrior’s path if they were to avoid extermination. What is fascinating today is the remarkable historical amnesia on the part of the Navajos and others regarding the well-documented warrior tradition of that tribe. The modern perception of Navajos as peaceful shepherds, silver artisans and weavers totally neglects their colorful past as the masters of the Southwest. In the 20th century, Navajo warriors have reaffirmed this grand tradition on the battlefields of WWII and on countless foreign battlefronts since. The Navajos, rightfully proud of their modern veterans, have seemingly forgotten these earlier warriors.

Two versions of the past are not necessarily exclusive. To the Navajo people, the story of Canyon de Chelly and the Long Walk remain a time of intense pain. They blame Kit Carson for that pain. He was their friend who came to fight against them. But in reality, they were fortunate that it was Carson, who knew and understood them, and not another soldier, like Sheridan or Custer or Miles—for the consequences would have been far worse. Unlike many Indian tribes, the Navajo still reside in their homeland, practicing a political and cultural autonomy that makes them remarkable. They avoided the dislocation suffered by other tribes by making their peace with the invading Americans in 1864. That transition, brought on by Carson, was indeed painful, but it made them stronger and ultimately preserved their nation.

Monuments to a Troubled Past

New Mexico has enthusiastically supported the creation of a memorial at Bosque Redondo for the Navajo victims of the Long Walk, and the state’s congressional delegation has also given strong support to the National Park Service for the creation of a Long Walk National Historic Trail. The Bosque Redondo Memorial was dedicated amidst much ceremony in June 2005, and the Long Walk Trail should be established this year. It is certainly fitting and proper that these commemorations take place.

While the state and federal governments have concentrated on Navajo history, the New Mexico Freemasons have raised private funds to restore Kit Carson’s adobe house in Taos. The house and museum opened in 1952, but the adobe had deteriorated so much and funding was so problematical that it shut down in 2004. After a $300,000 investment by the Masons, the museum and historic home officially reopened in September 2005.

Perhaps the official government commemoration of the tragedy of the Long Walk and Bosque Redondo will finally lead to a healing period for the Navajo. In turn, the newly refurbished Kit Carson home in Taos may help to educate the public about the major contributions to history by this greatest of all the frontiersmen. Between these two New Mexico monuments to a troubled past, a new, more balanced and shared history may yet emerge.

Kit Carson was neither saint nor sinner. He put it best in his own simple words: “I do not know whether I done rite [sic] or wrong, but I done what I thought was best.”

Paul Hutton is a professor of history at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.