“Free Ice Water. Wall Drug.”

“Free Ice Water. Wall Drug.”

Millions of motorists have seen this sign or its hundreds of variations. You can spot Wall Drug signs worldwide, even at the South Pole. As I drove west on Interstate 90, one sign in particular brought a smile to my face: “Wall Drug. Western Art.”

The town of Wall, north of Interstate 90 at the edge of South Dakota’s Badlands, is home to Wall Drug. Pharmacist Ted Hustead and wife Dorothy moved to Wall in 1931, buying the town’s only drugstore. Business was slow until 1936, when Dorothy came up with an idea to attract travelers from Highways 16 & 14—put up signs advertising free ice water. The signs were similar to the Burma Shave signs that told a story or rhyme, sign by sign. Dorothy’s slogan was: “Get a soda… Get root beer… Turn next corner… Just as near… To Highway 16 & 14… Free Ice Water… Wall Drug.”

As soon as the Husteads planted the signs, travelers began pouring into the store and the traffic never stopped. As the years progressed, they hired more staff and expanded the operation, until today it is more than just a drugstore, although you can still sip on free ice water or a steaming hot five-cent coffee. The Husteads sell Western jewelry, leather goods, clothing and books. But one of the top attractions is the Western Art Gallery Dining Room, where the road-weary traveler can order a buffalo burger and a Coke, and eat his meal surrounded by one-of-a-kind Western art.

Life doesn’t get much better than this.

Art History Lessons at Wall Drug

“Most people who come to the store have blinders on,” Ted Hustead says. “They walk through here, and they don’t look. But every now and then, we’ll get someone in who will say, ‘This is the most unbelievable collection of art I have ever seen.’ Or ‘Do you know this is the greatest illustration collection in the country?’ You get people like that who just go on and on.”

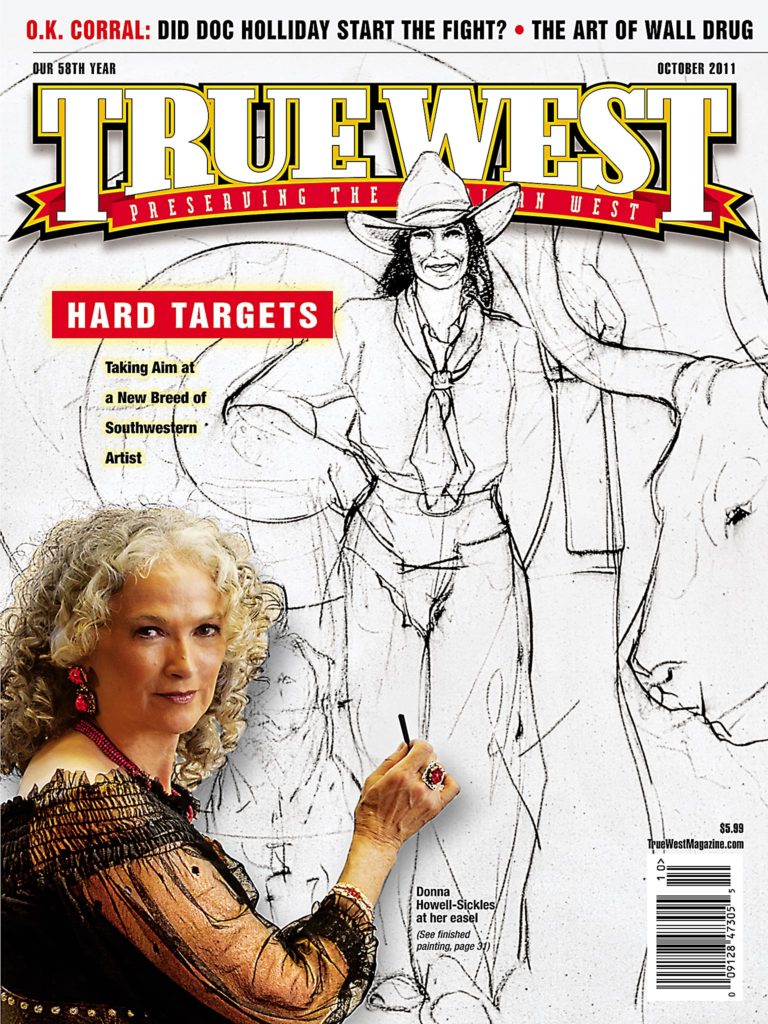

We like it when Ted Hustead goes on and on about Wall Drug’s art collection—all original works, no prints. In fact, that’s why Jim Hatzell and I were visiting with Ted, the grandson of Ted and Dorothy, and Wall Drug’s president. Jim had agreed to guide me on the Western art we’d be seeing at Wall Drug (he holds a degree in illustration from the American Academy of Art in Chicago, Illinois). Many True West readers know Jim’s work well; they voted him “Best Living Western Photographer” in 2009. Quite a few of today’s top Western artists know Jim as the director of the Artist Ride, held each August at the nearby Shearer Ranch along the Cheyenne River.

Jim knows Ted is not just blowing smoke about the art gallery. “I heard the same thing from the Artist Ride artists,” Jim says to Ted. “All these artists stop in at Wall Drug, and they go crazy over your collection.”

Anyone dining at Wall Drug’s café gets his first taste of just how special that collection is. The menu lists a few of the historical masters whose artworks can be found along the walls: “Please look for N.C. Wyeth, Harvey Dunn, Benton and Matt Clark, Harold von Schmidt, Morton Stoops, Will James and Frank McCarthy to name a few.”

Yet, how exactly did Wall Drug’s art collection get started?

“I think the first painting ever purchased, my grandfather bought it over 50 years ago,” Ted says. “It was an Andrew Standing Soldier painting. Andrew Standing Soldier painted the Native Americans as they were transitioning into cowboys on the reservation. He’s probably the most famous Native American artist coming out of South Dakota after Oscar Howe. We have eight Andrew Standing Soldier paintings.

“My father, Bill Hustead, is the one who really put the collection together. He started buying art in the late ’60s. He didn’t want just Western art, he wanted attractive art. He built the Art Gallery Café in the early ’70s. He wanted a restaurant the family, the town and he could be proud of.

“My father got into illustration art at a time when illustration art really wasn’t appreciated as much as it is now. People got over the fact that it was artists for hire, instead of an artist doing it for a higher purpose.”

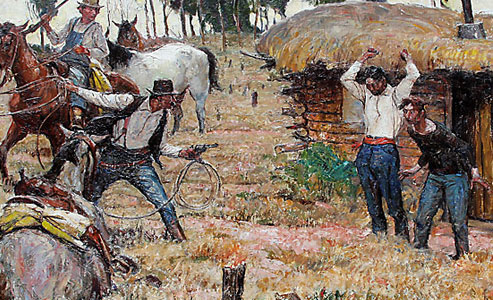

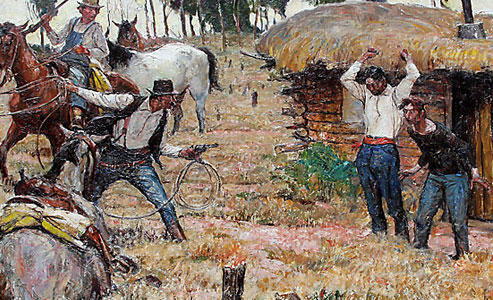

Ted now keeps the collection going. “The last Harvey Dunn painting I bought, Apprehending the Horse Thieves, is our best Dunn,” he admits. “You can stand far away and see the picture in sharp detail, then walk up close and see his impressionistic style.”

Of the 10 Dunn paintings in the store’s collection, one of his favorites, and his dad’s favorite too, is Prairie Homestead—a painting of Dunn’s boyhood home.

“Most illustrative artists don’t paint anymore, it’s all digital photography,” Ted says. “It’s a lost art. These paintings have a cultural value now. Norman Rockwell and the other illustrative artists tell the story of America.”

“That’s right,” Jim agrees. “Cowboy art originated in America and not in Europe. For instance, [look at] John Ford’s John Wayne cavalry films. Ford had a large collection of Frederic Remington paintings. He told his wardrobe people and cinematographers, ‘I want the scene set up like this painting.’”

When it comes to illustration art, the man who set the scene was Howard Pyle. “He started the Brandywine School of Art where N.C. Wyeth and Harvey Dunn studied,” Ted says. “If you want to rank the illustration artists, it would go something like this:

• Norman Rockwell (he painted 322 covers of Saturday Evening Post)

• J.C. Leyendecker (321 Saturday Evening Post covers)

• Howard Pyle (Father of illustration art; “I’d love to have one of his paintings,” Ted admits.)

• Maxfield Parrish

• N.C. Wyeth

• Dean Cornwell (check out Opening Shot)

• Harvey Dunn

• Frank Schoonover

“I think Harvey Dunn is right up there with Wyeth,” says Mike Huether, Wall Drug’s general manager, who Ted called over to join us. “But Wyeth got his name out there and was more popular. Dunn is every bit as good as Wyeth.”

“They all vacationed together in Colorado,” Jim says.

“I think it was Trinidad, Colorado,” Mike replies. “There’s a little bar there, where N.C. Wyeth, Harvey Dunn and the others used to

party. The town has several Harvey Dunn paintings.”

“N.C. Wyeth was supposed to have had the greatest collection of props and costumes out

of all those guys,” Jim says. “They all used Wyeth’s props and costumes, and they all modeled for each other. You see them in each other’s paintings.”

We were about to see one Wyeth painting that was Ted’s favorite

of all the artworks at Wall Drug. But before he led us to it, he

took us on a guided tour of the Western Art Gallery, where four dining rooms feature more than 300 pieces hanging on the black walnut walls.

Showcased in the slide show are Ted’s favorite paintings at Wall Drug.

Photo Gallery

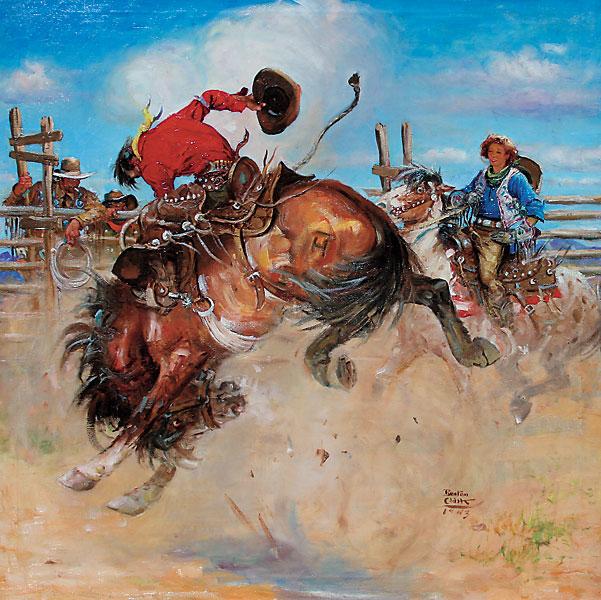

“People come through and see our artwork, and come to find a lot of it is very personal to them,” says Ted, as we stop at Bronco Buster, painted by Benton Clark.

“He really does just a beautiful job,” Ted says. “The other Clark, the one I showed you, the man and woman in the wagon? The woman who looked like Jane Russell? This is his brother. Their dad was a saddle maker, so the details on the saddles are exquisite. The reason is they grew up helping their father make saddles.”

“Notice the brand?” Jim asks. “You’re not going to see a lot of cowboy paintings where the horses are branded. You can tell these guys were ranchers, because they got all the important items on there.”

As Ted Hustead led Bill Markley and Jim Hatzell on a personal tour of his favorite paintings, Bill spied one he especially liked, Interrupted Supper by Herbert Morton Stoops.

Ted led us to another favorite painting, Gerald Farm’s Mixed Emotions. It shows a woman who has just tacked up a notice for a revival on the outside wall of a saloon. The expressions on the bystanders’ faces vary according to their sentiments.

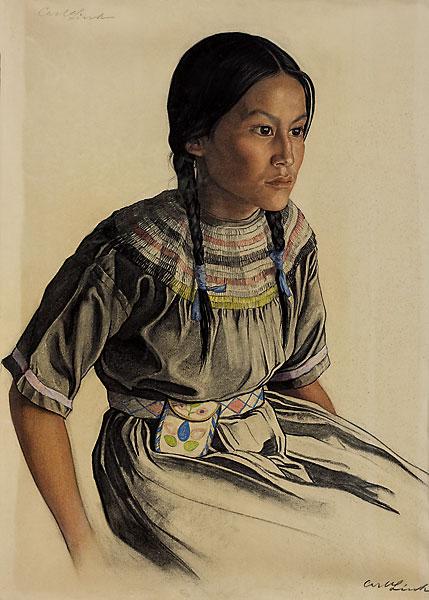

“We have a Carl Link,” Ted says. “He painted for Coca Cola, and he is most famous for painting the classic Santa Clauses with the rosy cheeks and horn-rimmed glasses….Link went to Montana in the ’30s and painted Native Americans. He did this beautiful charcoal and pencil piece of this Native American girl, she’s gorgeous; she’s beautiful. The paper is so old, it’s turned yellow, but nothing has changed on her.

“I was in a New York illustration house, and Walt Reed and his son Roger pulled down everything they thought I would be interested in. As I was walking out, I see this Native American girl, and I ask, ‘What is that?’

“Walt says, ‘Well, that’s a Carl Link.’

“I asked, “Where did you get that?’

“He said, ‘It was de-acquisitioned by the National Cowboy Hall of Fame [known today as the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum].’”

“The Cowboy Hall of Fame actually got rid of something?” Bill asks.

“Yeah!” Ted says. “I ended up buying it.”

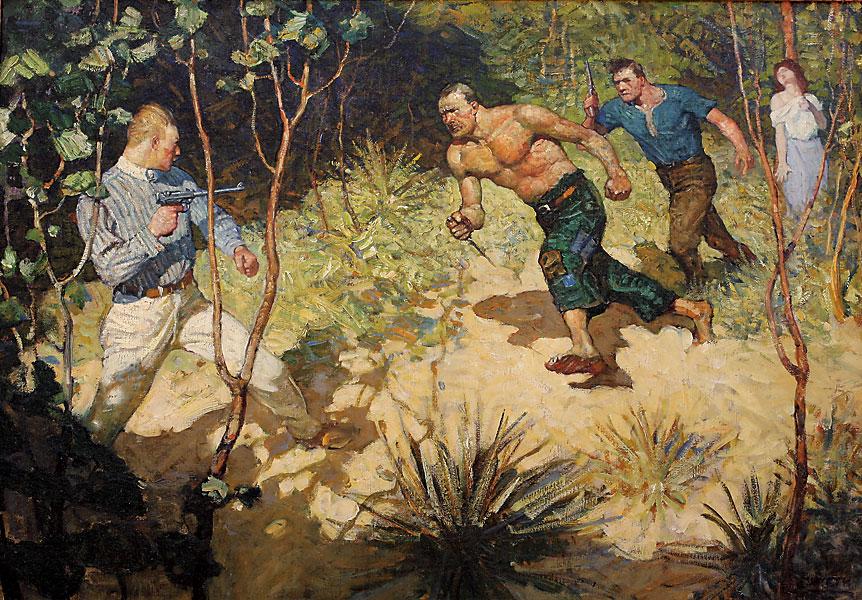

“Punching it Out, another Harvey Dunn,” Ted says. “This depicts the conflict between the cattlemen and the sheepherders. Of course, the sheepherders wanted open range, and the cattlemen wanted to fence it to keep the sheep out.”

“And this is a Gerald Farm again, Tea for Two,” Ted says.

“It’s one of the favorites,” Mike chimes in.

“We get lots of people who tell us they love it,” Ted says. “I had one guy come up to me, and he said, ‘It means so much to me.’ I asked, ‘Oh, like what?’ He said, ‘Youth and the elderly. Innocence and experience.’ He had all these comparisons.”

Ted Hustead loves telling folks about the original artwork in the Western Art Gallery Dining Room. Ted explains the background of Harvey Dunn’s Apprehending the Horse Thieves to visitors as they enjoy their meal.

– All photos by Sara Sharp / Wall Drug –

Ted stops in front of his favorite, The Devil’s Whisper, by N.C. Wyeth, which appeared in the December 13, 1919, issue of Collier’s weekly magazine.

“Let me tell you a little about this one,” Ted says. “This artist, from a Kansas City card company—.”

“Hallmark,” Mike adds.

“He was telling me about the painting. Look how Wyeth draws your attention to this guy on the left, and then here, and then here, and then here,” says Ted, as he points to the characters in the painting. “The Hallmark artist said Wyeth probably knocked this painting off pretty quick, in a few days.”

“This might be one of our Hollywood beauties on the wagon seat back in the ’50s,” Ted says of Matt Clark’s painting The General Store. “Look at the look on her face. The look on her face is like ‘What in the heck am I doing out here in this place? Why aren’t we in St. Louis or Chicago or New York?’ Of course, the man is possessive and protective.”

“Here’s Harvey Dunn’s The Miner,” Ted says. “Harvey Dunn did quite well with light and dark.”

“Yes, that’s amazing work,” Jim agrees. “To paint something like that is a real challenge.”

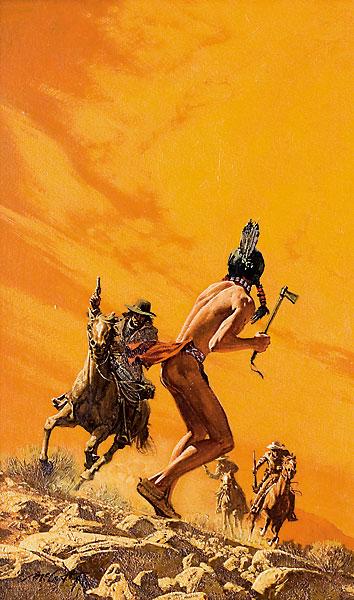

“Glanzman painted this for the cover of a Louis L’Amour book,” Ted says of Louis Glanzman’s Trail of Blood. “He did lots of paintings for magazines. Look at that face. A killer with a gun. See, this guy was a bounty hunter.”

“I love the blood trail and the smoke coming out of the gun barrel,” Jim says. “That tells a story—there’s two horses, one guy.”