First off, there were no male action stars and no hot babes, so there goes the action and sex-comedy crowds.

Look at the four biggest grossing films in the first two weeks The Alamo was released: Kill Bill 2, Hellboy, The Punisher and Walking Tall. Find the prototypical ticket buyer for those films and ask him (and it would surely be a he) if he remembers The Alamo.

When you haven’t got anything to lure the frat-house boys, you need strong critical support. The Alamo, I fear, was doomed on this count before its release. I don’t know if you know film critics, but I do—I even was one for a while—and I can promise you that people who please their bosses by getting their names under rave quotes in newspaper ads are not going to hitch their wagons to what appears to be a falling star—especially when it doesn’t have a name director who a hero-worshiping critic can get behind. Put John Lee Hancock’s name on The Gangs of New York and Martin Scorsese’s on The Alamo, and The Alamo would have drawn passionate defenses from at least half the critical establishment while Gangs would have been ignored.

A failure to release The Alamo last December practically guaranteed that it wouldn’t get good press reception in its severely cut-up form. (We really won’t know how good The Alamo is until it’s finally released in a special edition DVD.) How many reviews did you read that took up at least a paragraph reviewing the film’s “troubled history”? And in truth, that history started earlier, when Disney’s CEO Michael Eisner first announced the project by saying that this version would “capture the post-September 11 surge in patriotism.” You don’t have to be of liberal bent (although many critics are) to find that statement a little crass. Even though the final film was a great deal subtler than Eisner’s remark suggested it would be, many journalists never got that initial impression out of their heads.

Really, though, the question is not why The Alamo didn’t succeed but why anyone would have expected that it would. The Alamo is one of the most visible symbols of Americana, but when have Americans ever really cared much about seeing their own history on screen? (Has there ever been even one feature film about Valley Forge?) In point of fact, no Alamo movie has ever been a big financial success. The Last Command (1955) failed, and the John Wayne film drew as well as it did only because it starred Hollywood’s biggest box office draw and had a huge publicity campaign. On its own merits, Wayne’s Alamo would probably have been as big a failure as the new one. (Yes, there was Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett at the Alamo. But the success of that film was not due to the Alamo but to Walt Disney having turned Davy Crockett into a national craze before the release.)

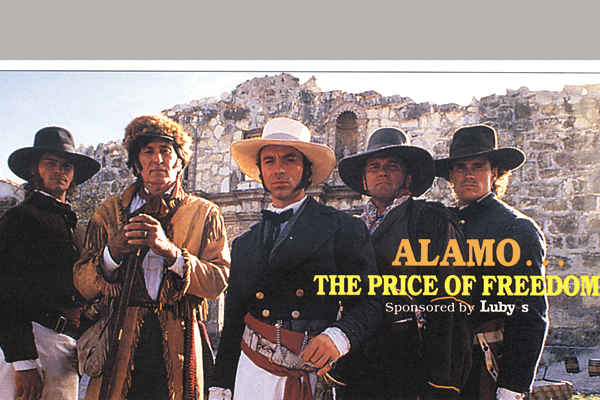

Which brings us to the one group who, if they had rallied in sufficient numbers, might have saved The Alamo, namely older men and perhaps a few women who know something about the history and lore of the subject. Here, after all, was the first and only film to offer realistic, detailed portraits of David Crockett, James Bowie, William Barrett Travis and Juan Seguin, and, for that matter, the Alamo itself. It is and will probably remain the only film to give any indication of the political complexities that lead to the battle, the only film to show the Mexican Army’s tortuous march to Bexar through the mountains in winter and the only film to offer a realistic Santa Anna and his relationships with his officers. It’s the only Alamo film to humanize the average Mexican soldier. It’s the only film that has ever given the viewer a realistic idea of the final assault itself (easily the most sensational nighttime battle scene since Glory).

And what happened? The Alamo nerds picked it to pieces because the chapel wasn’t quite in the right place, because every Mexican didn’t have quite the right uniform or because their favorite minor personage was cut from the film. Once again we see that curious phenomenon where the most historically accurate film on a subject is the one most brutally hammered by those you’d expect to appreciate it most.

The vast majority of Americans really know very little about the Alamo, and the ones who do tend to be proprietary to an absurd degree about the subject: if they can’t see their vision on screen, they don’t want any vision at all. For all their talk of historical accuracy, the buffs would, if you press them, prefer the sugarcoated myths of Disney and Wayne. Not that I don’t understand the appeal of those myths; I cherished them in my youth and still do. It’s sad that we can’t forge new myths out of historical realities, that we can’t see our old heroes as the flawed men they were and still accept them as heroes.

A poignant and much overlooked scene from the movie suggests itself here. The night before the assault, Jason Patric’s Jim Bowie and Patrick Wilson’s William Travis make their final peace with each other. “Buck,” says Patric, “if you live five more years, you just might be a great man.” “I fear,” says Wilson with a smile of resignation, “that I will have to settle for what I am now.”

So must we all. If we can no longer accept heroic, imperfect men as heroes, then we deserve no heroes at all.

Allen Barra is a former film critic for Newhouse Syndicate newspapers and currently writes a column on historical films for American Heritage magazine. He is also the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp: His Life and Many Legends.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Dena Newcomb / Touchstone Pictures –