It was quite natural for Wyatt Earp to gravitate to Gower Gulch, the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street in Hollywood, where unemployed Southwestern cowboys gathered daily in search of work in the new moving picture industry. Many old pals from his Arizona, Nevada and Alaska days were there. They would swap tales, warmly recalling the dead past as old men so often do.

It was quite natural for Wyatt Earp to gravitate to Gower Gulch, the intersection of Sunset Boulevard and Gower Street in Hollywood, where unemployed Southwestern cowboys gathered daily in search of work in the new moving picture industry. Many old pals from his Arizona, Nevada and Alaska days were there. They would swap tales, warmly recalling the dead past as old men so often do.

They also took note of the growing popular interest in all things Western, for as the generation that had tamed the West began to fade away, the public could not get enough of their adventures—both real and imagined. The movies offered hope for one final payday for old men desperate to support themselves in their waning years. Buffalo Bill Cody, Charlie Siringo, Emmett Dalton, Henry Starr and Bill Tilghman all tried their hand at the newfangled moving pictures. Earp, always on the lookout for the main chance, saw Gower Gulch as one last boomtown.

Earp met several important Hollywood players, for stories of his Western adventures had circulated throughout the new film community. Directors Alan Dwan, John Ford and Raoul Walsh all sought him out.

Ford, who knew how to spin a tall tale with the best of them, claimed a warm Earp friendship. “I knew Wyatt Earp,” he told film historian and director Peter Bogdanovich in 1967. “In the very early silent days, a couple of times a year, he would come up to visit pals, cowboys he knew in Tombstone; a lot of them were in my company. I think I was an assistant prop boy then and I used to give him a chair and a cup of coffee, and he told me about the fight at the O.K. Corral. So in My Darling Clementine, we did it exactly the way it had been.”

Of course, historical accuracy is not among the many virtues of Ford’s transcendent 1946 version of the Tombstone saga. So either Earp or Ford, or both, could not get the story straight.

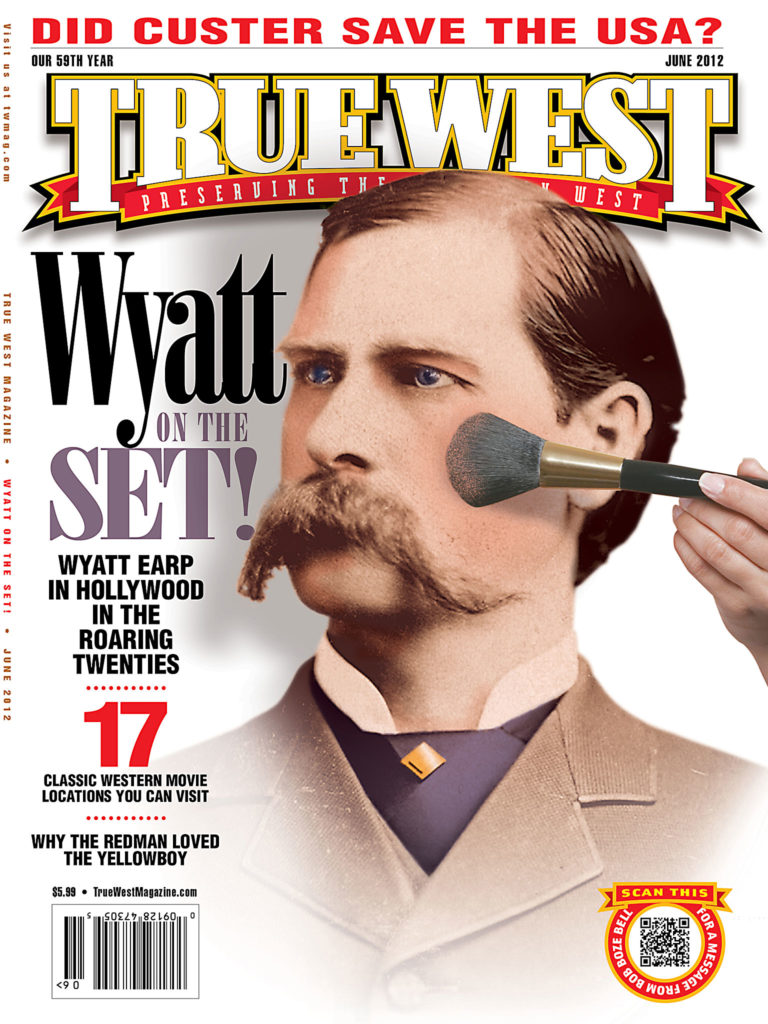

Earp’s closest friends in Hollywood were William S. Hart and Tom Mix, the two leading Western stars of the silent era. Earp had hopes of having his Western exploits, or his version of them, brought to the screen. He had been stung by several books and articles that had cast him and his Arizona adventures in a bad light. Hart had written the editor of the Los Angeles Times in 1922 to correct an outrageous bit of Wild West doggerel that the newspaper had published on Earp, leading Wyatt’s wife, Josephine, to thank him: “I feel deeply indebted to you for your kindness to us. It was a mighty big thought of yours and we highly appreciate it.”

Earp hoped that Hart might help bring his life story to the screen, writing in July 1925: “I am sure that if the story were exploited on the screen by you, it would do much towards setting me right before the public which has always been fed up with lies about me.”

Hart could not have sold Earp’s story to the studios, even if he had wanted to. By 1925 his star was in decline. That year Hart’s final film, Tumbleweeds, was released.

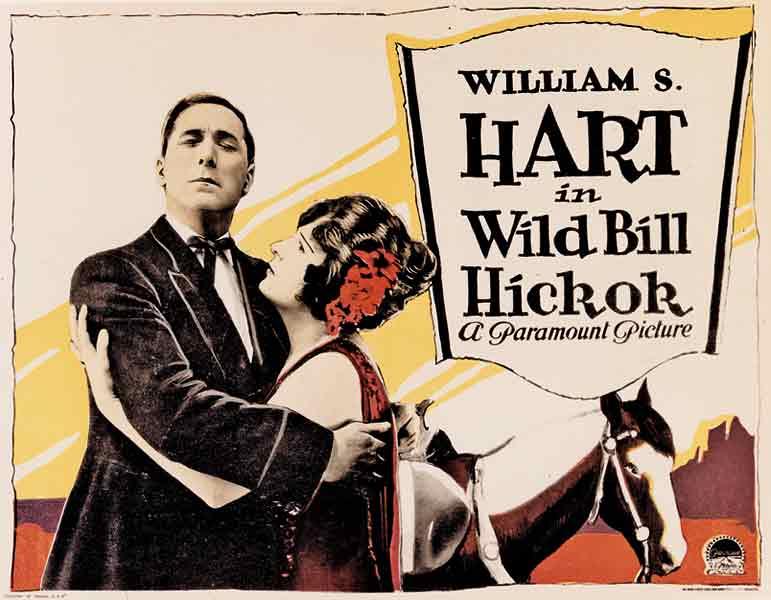

While Hart never developed the Earp story into a film, he was the first to introduce Earp as a character in a film. The seven-reel epic Wild Bill Hickok, released by Paramount in 1923, featured both Earp and Bat Masterson as important characters. It was also the first film to portray Doc Holliday on screen.

Hart wrote the original story, which J.G. Hawks turned into a film scenario, centering on Hickok’s return to gunfighting in order to assist the “Dodge City Peace Commission” of Masterson, Earp, Holliday, Charlie Bassett, Luke Short and Bill Tilghman in cleaning up the wild cowtown. (Hickok, Holliday and Tilghman were not historically part of the group.) The usual romantic entanglements made the job all the more difficult for Hickok, but, of course, he prevailed over the villain in a climactic final showdown.

“Back in the days when the West was young and wild, ‘Wild Bill’ fought and loved and adventured with such famous frontiersmen as Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp,” ran promotional copy for the film over Hart’s byline.

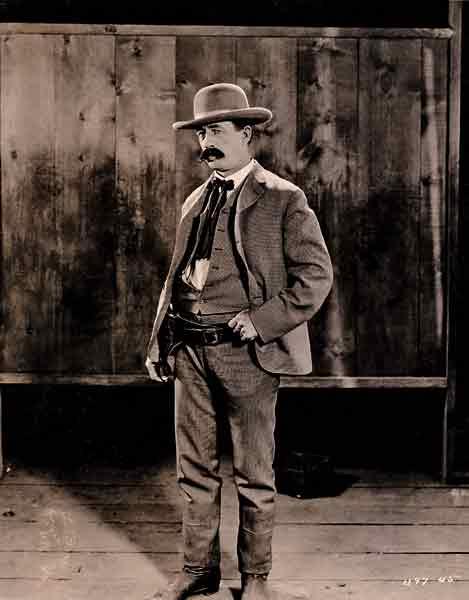

Actor Bert Lindley portrayed Earp, described in the promotional copy as “deputy sheriff to Bat Masterson of Dodge City, known as one of the three greatest gun-men that ever lived, along with Bat Masterson and ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok.”

Since Hart knew both men we may assume that considerable care was given to finding actors who closely resembled the men they played. Hart had earlier described himself as a “mere player” and “imitator” compared to Masterson and Earp: “[T]hese names are revered as none others. They are the last of the greatest band of gunfighters—upholders of law and order—that ever lived….Let us not forget these living Americans who, when they pass on, will be remembered by hundreds of generations. For no history of the West can be written without their wonderful deeds being recorded.”

Earp was naturally flattered by Hart’s portrayal of him on film, but there is no evidence he visited the set or consulted with Hart in any way. He did not help in promoting the film, as Bill Tilghman did when it played Oklahoma City.

After seeing the film, Josie wrote Hart a gushing letter on December 18, 1923: “Just a line to congratulate you upon your new picture ‘Wild Bill Hickok.’ I saw it twice with several friends and each time the house was packed. When you appeared upon the screen the applause was wonderful. Am happy to say that you have staged a remarkable ‘come back.’”

Audiences around the country, film critics and studio bosses did not share Mrs. Earp’s enthusiasm for the film. Its box office failure helped to end Hart’s already fading career.

Hart’s film failed to bring Earp the fame, redemption and financial security he craved. The old frontiersman had been correct, however, when writing Hart in 1925 that the movies might yet set the record straight. When Earp died at his rented Los Angeles bungalow, with Josephine at his side, on January 13, 1929, he could not have imagined that Hollywood would make him into a towering international legend.

With over 30 Earp films to date, Hollywood ended up most instrumental in creating and nurturing the image of Earp as the archetypical frontier lawman.

As an honorary pallbearer at Earp’s funeral, Hart helped to lay the real man to rest. But with his 1923 film Wild Bill Hickok, he had given birth to the legendary celluloid marshal.

Paul Andrew Hutton is distinguished professor of history at the University of New Mexico. His latest book is Western Heritage from University of Oklahoma Press.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton unless otherwise noted –

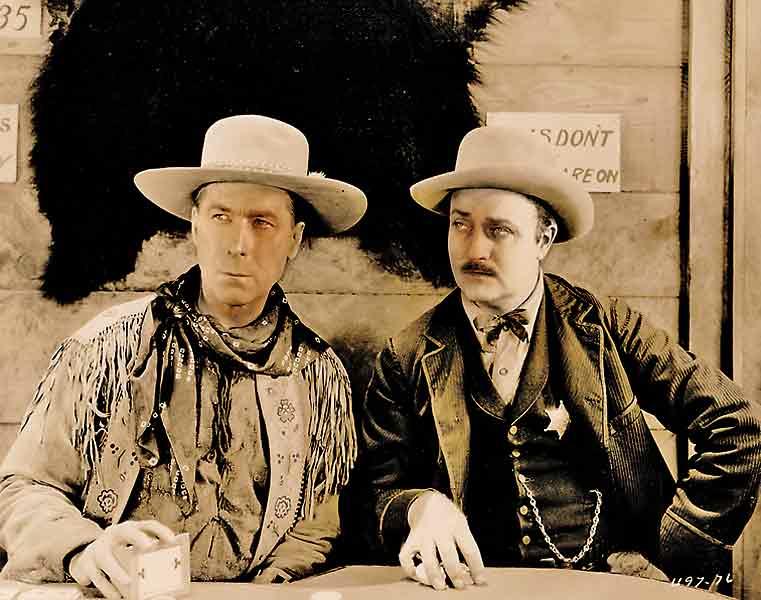

The studio caption reads: “The Dodge City Peace Commission meets the pompous buffalo hide buyers, the silk hat brigade, from Boston.” William S. Hart as Hickok, Jack Gardner as Masterson and Bert Lindley as Earp make up the commission, with unknown actors in the group playing Doc Holliday, Bill Tilghman, Luke Short and Charlie Bassett.

– Courtesy William S. Hart Collection, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History –