Geronimo. It is a warrior name for the ages—standing comfortably alongside the likes of Achilles, Leonidas, Genghis Khan, Patton and Rommel in its power—a storied name invoking cunning, courage, tenacity and uncompromising ferocity.

Geronimo. It is a warrior name for the ages—standing comfortably alongside the likes of Achilles, Leonidas, Genghis Khan, Patton and Rommel in its power—a storied name invoking cunning, courage, tenacity and uncompromising ferocity.

On the territories of New Mexico and Arizona, and across northern Mexico, it was a synonym for terror throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

In WWII, it became a famed battle cry for American airborne forces as they hurled themselves into the sky to descend upon their foreign foes—a 20th-century version of “Remember the Alamo!”

During the turbulent 1960s, when Berkeley street folk squatted on a vacant lot belonging to the University of California, renaming it “Power to the People Park,” and posted leaflets bearing Geronimo’s image alongside the declaration “Your land title is covered with blood,” it was double-edged, both a statement and a warning.

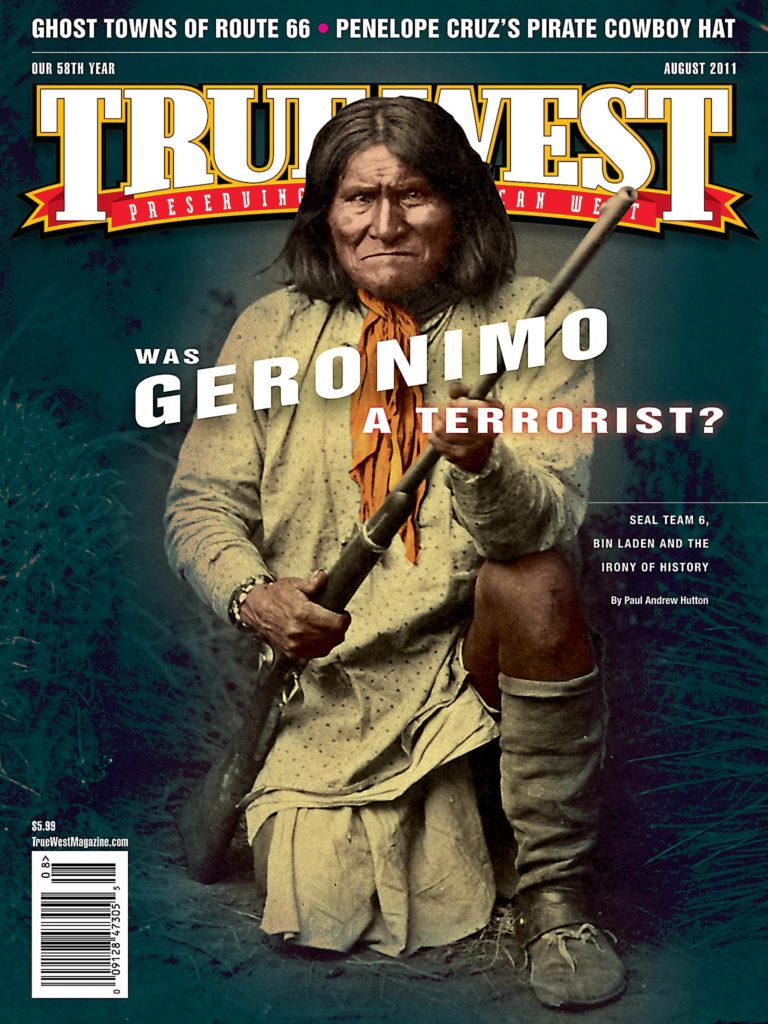

After 9/11, posters and T-shirts bearing the famous C.S. Fly photograph of Geronimo and his fellow warriors, and the words “Homeland Security: Fighting Terrorism Since 1492” became popular.

When U.S. troops invaded Afghanistan, they established Camp Geronimo as a forward base.

On May 2, 2011, when Navy SEALs finally killed the elusive terrorist mastermind Osama bin Laden, they sent back the message “Geronimo EKIA.”

The resulting outcry over the use of the Geronimo code name proved an embarrassment for a White House that prides itself on its racial sensibilities. Military authorities backpeddled, quickly claiming that it was the code name for the mission, not the terrorist target himself. That semantic distinction did not satisfy American Indian activists and their political supporters. New Mexico Democratic Sen. Tom Udall denounced the code name at a Senate hearing: “I find the association with bin Laden to be highly inappropriate and culturally insensitive. It highlights a serious issue…a socially ingrained acceptance of derogatory portrayals of indigenous peoples.” Harlyn Geronimo, Geronimo’s great-grandson, denounced the use of his ancestor’s name as well: “Obviously, to equate Geronimo with Osama bin Laden is an unpardonable slander of Native America and its most famous leader in history.” The dustup then conveniently became the centerpiece of the U.S. Senate’s Indian Affairs committee hearings on racial stereotyping of indigenous peoples.

Be the term a slander or a homage to a storied warrior, the use of Geronimo’s name by the heroic Navy SEALs who killed Osama bin Laden is reflective of the famed Apache’s transition into a historical icon of considerable symbolic power. From a renegade warrior, hated by settlers on both sides of the international border and finally tracked down by his own people, Geronimo has morphed into a patriot leader who led the final resistance to preserve his land and culture. Forgotten now is the misery, death and deportation he brought on the Chiricahuas, as well as the innocent American and Mexican victims of his raids. The story of that transition is a fascinating tale of historical amnesia and the shifting popular concepts of our shared national history.

A Warrior is Born

The grandson of the great Bedonkohe Apache chief Mahko was born in the early 1820s on the headwaters of the Gila River along what is now the New Mexico-Arizona line. Both states now claim him, although neither territory wanted him 125 years ago. His family named him Goyahkla—“One Who Yawns.” His people followed Mangas Coloradas, moving easily both north and south of the new political line that ran through the heart of their traditional country after 1848. Goyahkla became a leading warrior in the many raids that the mighty Mangas led deep into Mexico.

These nomadic raiders made a keen distinction between war for booty and war for vengeance. They soon had good cause to seek the latter. Janos, in the Mexican state of Chihuahua, was a favorite haunt of Mangas and his people, for the local Mexicans provided an eager market for their stolen booty, which was in turn sold to unsuspecting third parties in El Paso, Texas. In March 1851 Mangas and his warriors were enjoying the hospitality of their Janos business partners when Sonoran militia under Col. Jose Maria Carrasco attacked their village, slaughtering the defenseless Apache women and children. Among the dead were Geronimo’s aged mother, young wife and three children. Thus did vengeance become the driving passion of his life. Near the end of his life he was asked if he had any regrets. “I’m sorry I did not kill more Mexicans” was his simple reply. He soon led a bloody vengeance raid deep into Mexico that won him his Mexican name, Geronimo. He emerged from it as a great war leader, even credited with mystical powers, but he was never a chief like Mangas or Cochise.

He was at the July 1862 Battle of Apache Pass with Mangas and Cochise. After the 1863 murder of Mangas by New Mexico troops at Pinos Altos, Geronimo raided south constantly, often in the company of the equally hostile Juh, refusing to abide by the 1872 peace treaty between Cochise and Gen. O.O. Howard.

In 1877 Indian agent John Clum and his Apache police captured Geronimo at Warm Springs Agency, northwest of modern-day Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, and transported him in chains to San Carlos in Arizona. Soon released from imprisonment he bolted San Carlos with Juh to join Victorio in his 1879 war. In 1882 he and Juh led the stunning raid on San Carlos that liberated the dead Victorio’s people, now led by Chief Loco. Loco and others later claimed that they had been kidnapped, not rescued, and they blamed Geronimo for the sufferings afterward endured by the tribe. General George Crook’s 1883 campaign into the Sierra Madre forced Geronimo back to San Carlos, but he remained there only a few months. He blamed his outbreak on an old enemy, the enigmatic scout Mickey Free.

Crook was committed to the use of Apache scouts, and historians have since continually praised him for this innovation. This particularly annoyed his close friend and military superior Lt. Gen. Phil Sheridan. Sheridan felt that more direct action should be taken against Geronimo to quickly solve the problem. In retrospect, when one considers all the carnage and suffering that followed (especially for the Chiricahuas), perhaps he was right. The tenacity of the Americans and the Apache scouts convinced Geronimo that he could find no sanctuary. At first agreeing to surrender to Crook, Geronimo got drunk and bolted at the last minute. This cost Crook his command.

General Nelson A. Miles took command in Arizona, making a great show of force with his regular troops to satisfy both Gen. Sheridan, who distrusted the Apache scouts now more than ever, and the hysterical territorial press that was clamoring for the extermination or the removal of the Chiricahuas from Arizona. By the summer of 1886, Miles had 5,000 American troops (a full quarter of the U.S. Army) in pursuit of Geronimo and 34 Apaches. The national press breathlessly followed the story. Miles quietly used Crook’s Apache scouts, now led by Lt. Charles Gatewood, to flush out Geronimo and convince him to return to Arizona. Geronimo finally agreed to surrender in September 1886.

A Rising Star

Geronimo and his renegades, along with 500 of the peaceful Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apaches, including several of the loyal Apache scouts, were to be imprisoned in Florida. The farther east the prisoners traveled the less hostile became the crowds who came to gawk at them at train stations. When the train stopped in San Antonio, Texas, the local newspaper reported that the “bloodthirsty villains are gawked at, covered with given flowers and delicacies, as if they were heroes.” At Fort Pickens in Pensacola Bay, Florida, the captive Apaches instantly became a tourist attraction. “You can go over to Santa Rosa Island, see Fort Pickens and Geronimo,” declared the Pensacola Commercial, “and gather beautiful shells and marine curiosities on the beach.” The local press was outraged when the Indians were moved to the supposedly more healthful climes of Mobile, Alabama, in May 1888. “Just think of it, our Big Injun, and large-sized curiosity, Geronimo, together with those held with him at Fort Pickens were conveyed to Mobile,” lamented The Pensacolian.

The folks in Mobile were elated. “The placing of the Indians at Mt. Vernon will add greatly to the attractiveness of that place as a Sunday school picnic resort,” gleefully proclaimed the Mobile Register. Not all visitors were as smitten with Geronimo; one observed that the Apache was “about as mild mannered a man as ever scuttled a ship or cut a throat and for that matter butchered defenseless women and children.”

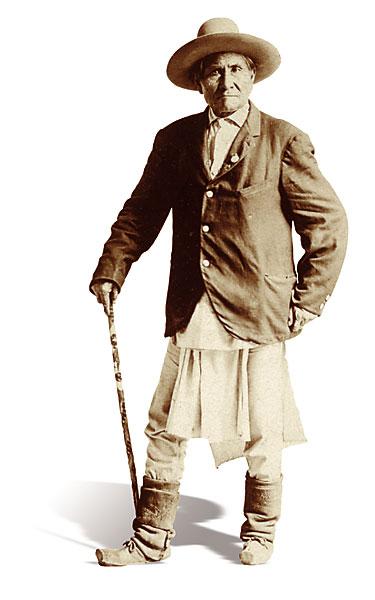

In 1894 the government moved the remaining Apache prisoners to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Tuberculosis had taken a fearful toll on them in Florida and Alabama so that only 300 remained, and many of those were children born during the period of captivity. Geronimo remained a celebrity of sorts, especially as memories of his wartime atrocities faded. He was exhibited at the 1898 Omaha exhibition, the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York (where President McKinley was assassinated), and the 1904 St. Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition. At the latter Geronimo had his own booth, where he sold autographs for 10 cents and photographs for $2. “The old gentleman is pretty high priced,” noted exhibit organizer S.M. McCowan, “but then he is the only Geronimo.”

“I often made as much as two dollars a day, and when I returned I had plenty of money,” Geronimo recalled of his time in St. Louis. Indeed, at the time of his death he had an estate worth several thousand dollars (so the famous photo of him in a top hat at the wheel of an automobile—immortalized in Michael Martin Murphey’s 1972 hit song “Geronimo’s Cadillac”—has considerable truth to it).

Geronimo’s greatest triumph as a celebrity came when he marched in President Theodore Roosevelt’s March 1905 inaugural parade. He rode alongside Quanah Parker down Pennsylvania Avenue, not far behind the President. Woodworth Clum, son of the Indian agent who had once captured Geronimo and a member of the inaugural committee, stood next to the President as Geronimo passed the reviewing stand in front of the White House. “Why did you select Geronimo to march in your parade, Mr. President?” Clum asked. “He is the greatest single-handed murderer in American history.”

“I wanted to give the people a good show,” the President replied.

It was a grand show indeed, and Geronimo would capitalize even more on that celebrity. Like other frontier heroes Davy Crockett, Black Hawk, Kit Carson and Buffalo Bill, he wrote an autobiography (he dictated it through a translator to Lawton, Oklahoma, schoolteacher S. M. Barrett). Like most such works his 1906 tome was filled with self-justification, although it also contained much valuable information on Apache life. Equally important in establishing his reputation were memoirs by those who had battled him—Britton Davis, Tom Horn, John G. Bourke, John Bigelow, Anton Mazzanovich and Nelson Miles.

On a cold February morning in 1909 Geronimo rode into Lawton to sell some bows and arrows. With the proceeds he bought whiskey and became so drunk that he fell off his horse on the way home. Laying half submerged in a creek all night, he contracted pneumonia and died on February 17. It was a sad ending for the man who arguably was the most famous American Indian who ever lived.

Popular Culture Wars

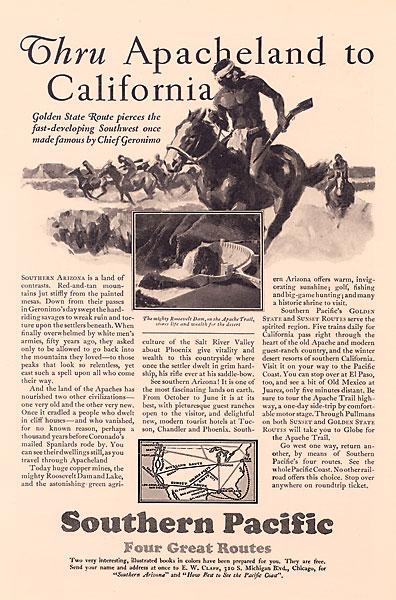

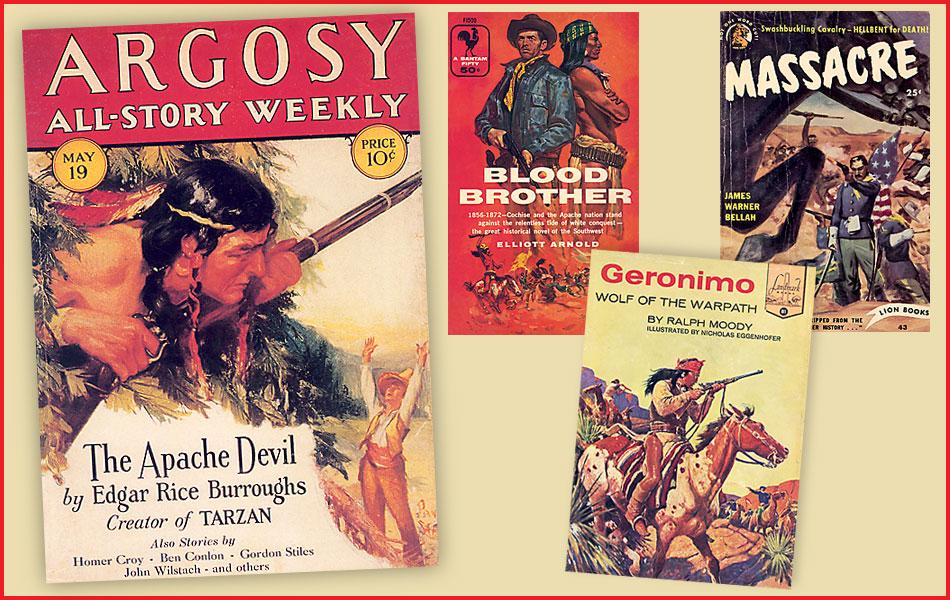

Geronimo and the Apache Wars were already topics of popular fiction before the old warrior’s death. Charles King, the 5th cavalry officer-turned-novelist, used Arizona as a setting for a dozen of his 50 novels on the military frontier (his novels, in turn, influenced 20th-century writers and filmmakers such as James Warner Bellah and John Ford). The writings and artwork of Frederic Remington also shaped public opinion around the heroic soldiers and stoic natives of the desert. Edward S. Ellis in his 1908 novel Trailing Geronimo, Everett T. Tomlinson in his 1920 potboiler The Pursuit of the Apache Chief and Forrestine C. Hooker, a frontier army brat who married a famed Arizona cattleman, in her 1924 novel When Geronimo Rode all painted the Apache warrior as the darkest of bloodthirsty villains.

A defense of Geronimo came from a rather surprising author in 1927. Edgar Rice Burroughs, the creator of Tarzan, had engaged in several forlorn pursuits of the Apache Kid as a 7th Cavalry private at Fort Grant, Arizona, before a heart condition led to his discharge in 1897. Now a master of pulp fiction, he intended to write an Apache trilogy featuring Geronimo as the adoptive father of his white Indian hero Shoz-Dijiji, but he became so exasperated with Argosy magazine’s criticism of his positive portrayal of the Indians that he finished only two books: 1927’s The War Chief and Apache Devil, first serialized in Argosy All-Story Weekly in 1928 and then published in hardback in 1933.

In the Burroughs books Geronimo seeks peace, but is forced onto the warpath by repeated white duplicity. In Apache Devil he explains his frustration to Gen. Crook: “Usen seems to have made one set of laws for the Apaches and another for the white-eyed men. It is right for the white-eyed men to come into the country of the Apaches and steal their land and kill their game and shut the Apaches up on reservations and shoot them if they try to go to some other part of their own country; but it is wrong for the Apaches to fight with the Mexicans who have been their natural enemies since long before the white-eyed men came to the country…Yes, Geronimo hears; but he does not understand.”

Burroughs’ interpretive stance, so firmly in the James Fenimore Cooper tradition of Indian-themed fiction, was carried forward by talented novelists such as Will Levington Comfort in Apache, his 1931 novelization of the life of Mangas Coloradas, and Paul I. Wellman in Broncho Apache, his 1936 saga of the renegade Massai (later filmed as Apache in 1954 with Burt Lancaster as Massai and Monte Blue as Geronimo). This trend reached its climax, both in terms of literary quality as well as cultural influence, with the 1947 publication of Elliott Arnold’s Blood Brother, the classic tale of the friendship between Cochise and Tom Jeffords that brought a brief peace to Arizona. It was filmed as Broken Arrow in 1950 by Delmer Daves, starring James Stewart as Jeffords and Jeff Chandler as Cochise, while Jay Silverheels portrayed the recalcitrant Geronimo. The casting of Chandler, a white actor, and Silverheels, a mixed-blood Mohawk from Canada, was a return to Cooper’s good/bad Indian dichotomy from Last of the Mohicans with the heroic Uncas and the evil Magua.

Broken Arrow, a commercial triumph, led Hollywood to embrace a far more positive view of Indians on the silver screen. Burned by public reaction to social commentary films on the black civil rights question, filmmakers like Daves retreated to the safer climate of the Western to make their pleas for racial justice. Broken Arrow’s impact in film was akin to the stunning shift in American cultural views of Indians wrought by Dee Brown’s bestselling Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee in 1970. In countless Westerns since the silent era Hollywood had treated Indians as part of a harsh landscape to be overcome by heroic white pioneers. While Westerns had long been populated by noble red men, crooked Indian agents and venal whiskey traders, few films before Broken Arrow attempted to fully develop the basic humanity of Indian characters.

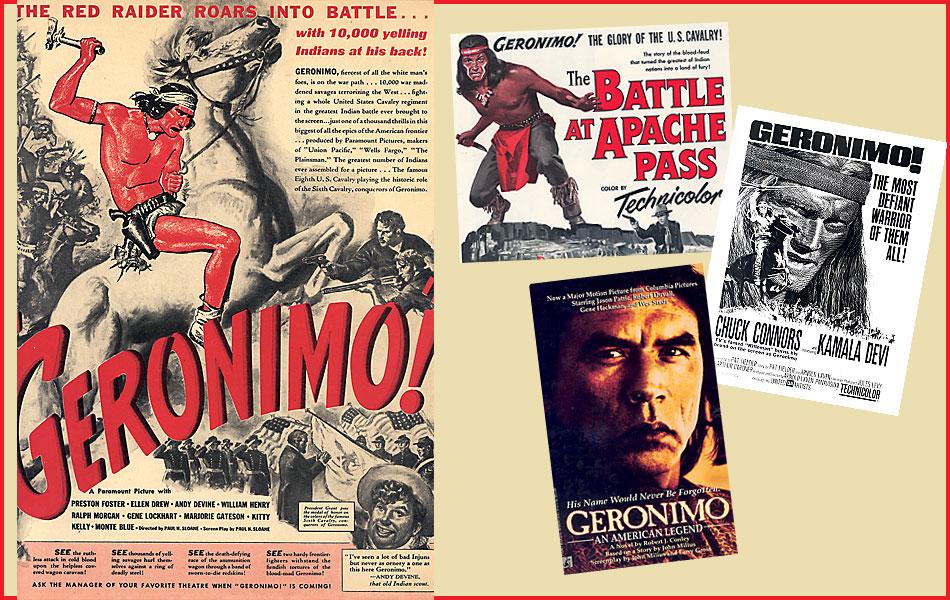

In these early Westerns Apaches were generally portrayed as more cruel and savage than Plains tribes like the Sioux and Cheyenne. For example, in John Ford’s Stagecoach in 1939 it is Geronimo’s outbreak that shadows the film’s drama. Chief White Horse, in a non-speaking but ominous role, had an uncanny resemblance to the real Apache warrior. The success of Ford’s film led to a major revival of big budget Westerns and made John Wayne a star.

Films could also change the course of history. For 1939’s Geronimo, Paramount’s publicity department gave wide circulation to the story that paratroopers at Fort Benning had viewed the movie before a test jump and used its name as a battle cry. This was altogether fitting since the plot—a simple love story between Preston Foster and Ellen Drew—was a commentary on the coming world war, with Geronimo’s Apaches as stand-ins for the German fascists. The airborne battle cry quickly spread to all five airborne divisions. The 501st Parachute Infantry Battalion adopted Geronimo’s name on its unit insignia patch in 1941. Lieutenant Col. Byron Paige, of the 11th Airborne Division, even wrote a song—“Down from Heaven”—about the Geronimo battle cry.

Down from Heaven comes Eleven

And there’s Hell to pay below

Shout “Geronimo, Geronimo”

It’s a gory road to glory

But we’re ready here we go

Shout “Geronimo, Geronimo”

As the gallant men of the 101st Airborne Division prepared themselves to truly drop into Hell on the eve of D-Day, many cut their hair into Mohawks and marked their faces with Indian warpaint in homage to the warrior tradition of Geronimo.

With WWII over, the Apaches returned as the foe in two of John Ford’s cavalry trilogy—1948’s Fort Apache and 1950’s Rio Grande, both based on James Warner Bellah short stories. Few authors ever matched the vitriolic anti-Apache tone of Bellah. He began his 1951 novel The Apache with: “It can be the phase of the moon that maddens Apaches, or a word from the memory of a medicine chief, or a strange flower by the trailside, or an omen of blood in a stone; because Apaches hate life and they are the enemies of all mankind…that is what Apache means: enemy.”

The 1960 Disney film Geronimo’s Revenge would be the last villainous portrayal of Geronimo, as Hollywood screenwriters joined with their literary cousins in portraying the Apache warrior as a heroic defender of native rights against the duplicitous white invader. Chuck Connors was cast in the title role of the 1962 film Geronimo, where his warrior spirit was finally compromised by his desire to provide peace for his people and his family. Similar heroic portrayals of Geronimo were presented on television in 1979’s Mr. Horn, 1990’s Gunsmoke: The Last Apache, 1993’s Geronimo starring Joseph Running Fox and a 1988 PBS American Experience special. All of these shows emphasized Geronimo’s spiritual side over his warrior qualities, and in each one he was the doomed heroic protagonist.

Walter Hill’s Geronimo in 1993, Hollywood’s final homage to the great warrior, was written by John Milius (of Apocalypse Now, Conan the Barbarian and The Wind and the Lion fame), so audiences might have expected a more realistic and violent portrayal of the native hero. The nervous studio softened the script into yet another stereotypical Uncas-like portrayal. Wes Studi, who had portrayed Magua so brilliantly in Michael Mann’s classic 1992 version of Last of the Mohicans, was reduced to a rather mild-mannered Uncas in Hill’s film. Geronimo, the greatest of warriors, had become too dangerous a topic for Hollywood to handle with any true realism. Better to have aliens or Orcs as your movie villains.

Fiction writers marched in lockstep behind the saintly Geronimo image, especially after the Vietnam-era shift in the national popular culture view of Indian history. Hunter Ingram’s 1975 novel Fort Apache set the perfect self-loathing tone when one character proclaims to an army officer: “Have you ever stopped to realize that the Caucasian race is the scourge of the earth? The Apache kills on an individual basis. The white race kills on a mass basis.” In Ingram’s novel, as well as Robert Vaughan ’s 1983 Savages, Geronimo wants only peace and justice, but is forced onto the warpath by the murderous whites. Forrest Carter, now notorious for his faked bestselling 1976 memoir The Education of Little Tree, published his Geronimo novel Watch for Me on the Mountain in 1978. His Geronimo has some real grit (Carter was the author of the brutally realistic novel The Vengeance Trail of Josey Wales), but is also a deeply spiritual leader with magical powers. He is portrayed as an Apache Moses and, like the old prophet, cannot be humbled by his captors (in this case John Clum and Naiche): “His hands were bound with chains, and the soldiers led him by a rope looped around his neck…His eyes fastened full on Naiche’s. The eyes gave no evidence of his humbled condition; they flashed black and fanatical. He said nothing. He was Geronimo.”

The Patriot

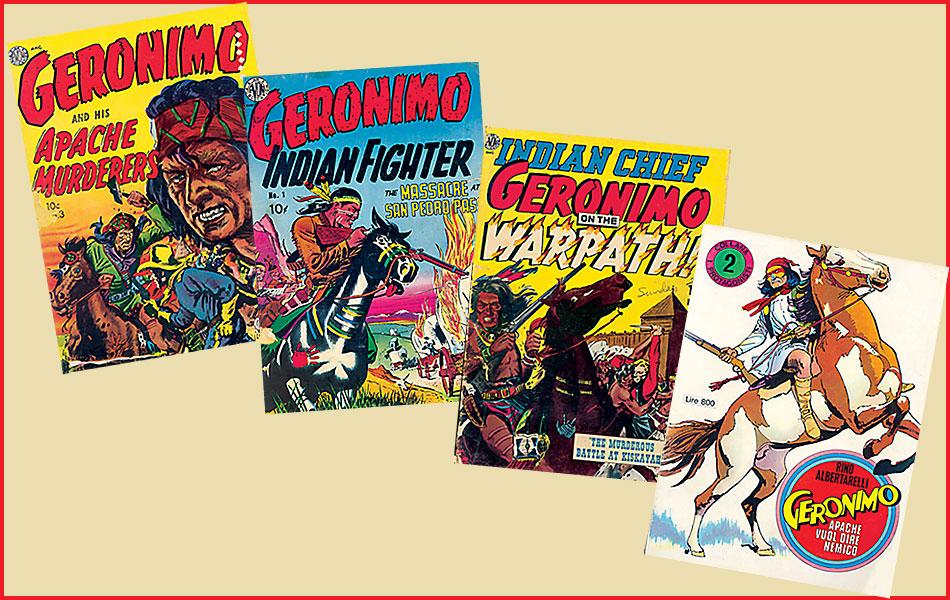

Throughout the last quarter of the 20th century even comic books, which had inherited the sensational graphics of the pulp magazines, shifted from bloodthirsty Geronimo to the peacemaker Geronimo. Children’s biographies followed suit, presenting a string of increasingly noble Geronimos to inspire the youth of America.

The U.S. government, in what might easily be viewed as acts of more hypocrisy than contrition, honored Geronimo with a 1993 postage stamp. A February 2009 U.S. House resolution declared him a “spiritual and intellectual leader” who “led his people in a war of self-defense.”

The old warrior must be spinning in his grave. But wait—is he really there? A 2009 lawsuit by Harlyn Geronimo claimed that his ancestor’s skull had been stolen by the Skull and Bones Order at Yale University. Harlyn’s desire to move Geronimo’s remains (with or without the skull) from Fort Sill to New Mexico has led to a nasty feud between the Oklahoma and New Mexico descendants of the Apache warrior.

So the transition from bloodthirsty terrorist to patriot chief is complete. Now officially sainted as a native “spiritual and intellectual leader” by the U.S. Congress that had once sent a quarter of its military forces to destroy him, Geronimo—“He Who Yawns”—has certainly had the last laugh. Peace to his bones—wherever they are.

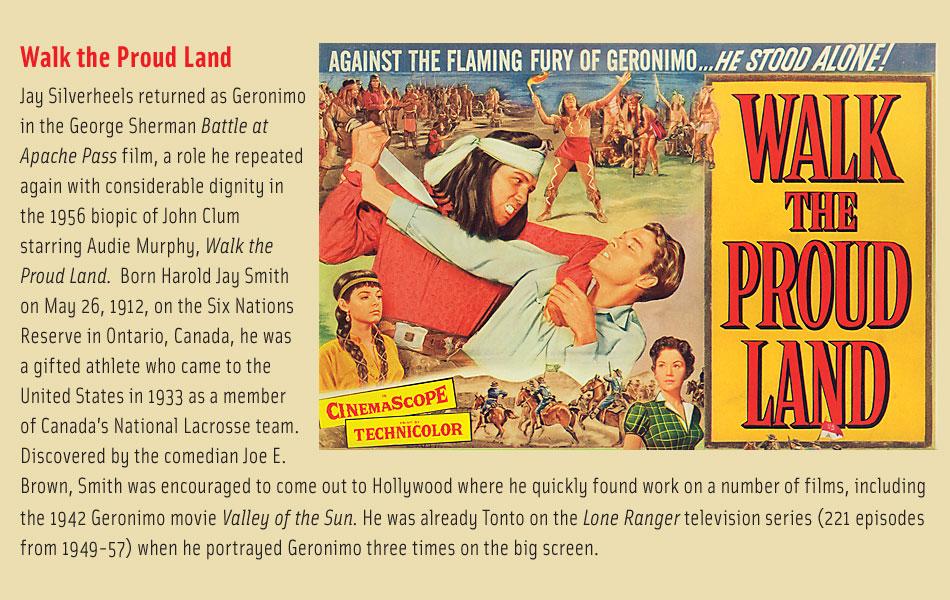

Walk the Proud Land

Jay Silverheels returned as Geronimo in the George Sherman Battle at Apache Pass film, a role he repeated again with considerable dignity in the 1956 biopic of John Clum starring Audie Murphy, Walk the Proud Land.

Born Harold Jay Smith on May 26, 1912, on the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario, Canada, he was a gifted athlete who came to the United States in 1933 as a member of Canada’s National Lacrosse team.

Discovered by the comedian Joe E. Brown, Smith was encouraged to come out to Hollywood where he quickly found work on a number of films, including the 1942 Geronimo movie Valley of the Sun. He was already Tonto on the Lone Ranger television series (221 episodes from 1949-57) when he portrayed Geronimo three times on the big screen.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –

– All photos True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –

In 1886, Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly accompanied Gen. George Crook to Cañon de los Embudos in Sonora, Mexico, and took a series of photographs of Geronimo and his warriors before the surrender. These rank among the greatest history photographs ever made. Shown here are (from left) Yahnozha, Chappo, Fun and Geronimo. After 9/11 the image was used on t-shirts and posters proclaiming “Homeland Security: Fighting Terrorism Since 1492.”

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –

– Courtesy Paul Andrew Hutton –