The dawning of the 20th century brought little improvement to the notorious reputation Arizona had earned during the tumultuous years of outlawry and the Indian Wars. The close proximity to Mexico and the rugged mountain wilderness in the eastern part of the territory made Arizona the sanctuary of choice for outlaws who had been driven out of other parts of the Southwest.

The dawning of the 20th century brought little improvement to the notorious reputation Arizona had earned during the tumultuous years of outlawry and the Indian Wars. The close proximity to Mexico and the rugged mountain wilderness in the eastern part of the territory made Arizona the sanctuary of choice for outlaws who had been driven out of other parts of the Southwest.

The remoteness of the terrain made pursuit and apprehension of these desperadoes next to impossible. Local ranchers lacked the ability to combat the gangs who brazenly rustled cattle on both sides of the border. Cattle rustlers operated in broad daylight and even bragged about it. Many ranchers feared the outlaws so much that when a posse did enter a remote area, they were reluctant to point fingers, for fear of retribution after the lawmen left.

County lawmen were not legally allowed to cross into another county in hot pursuit. Residents desperately cried out for a force of territorial rangers who would not be bound by county lines.

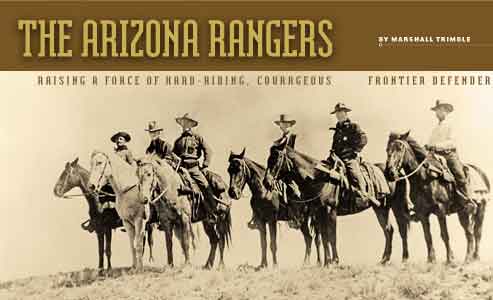

In 1901, Gov. Nathan Oakes Murphy decided to take strong action against the smugglers and rustlers by organizing a company of lawmen patterned after the storied Texas Rangers. Succumbing to pressure from the troubled parts of the territory, the legislature passed a bill to establish the Arizona Rangers on March 21.

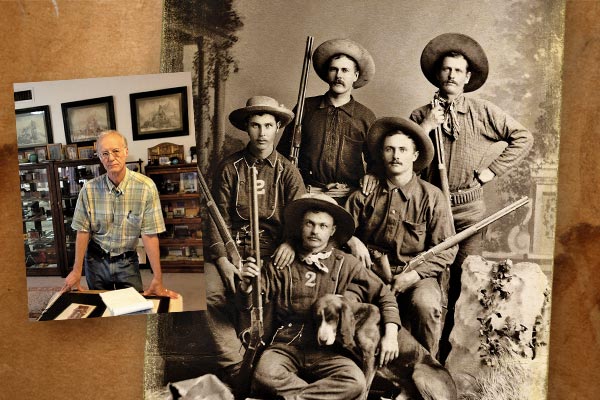

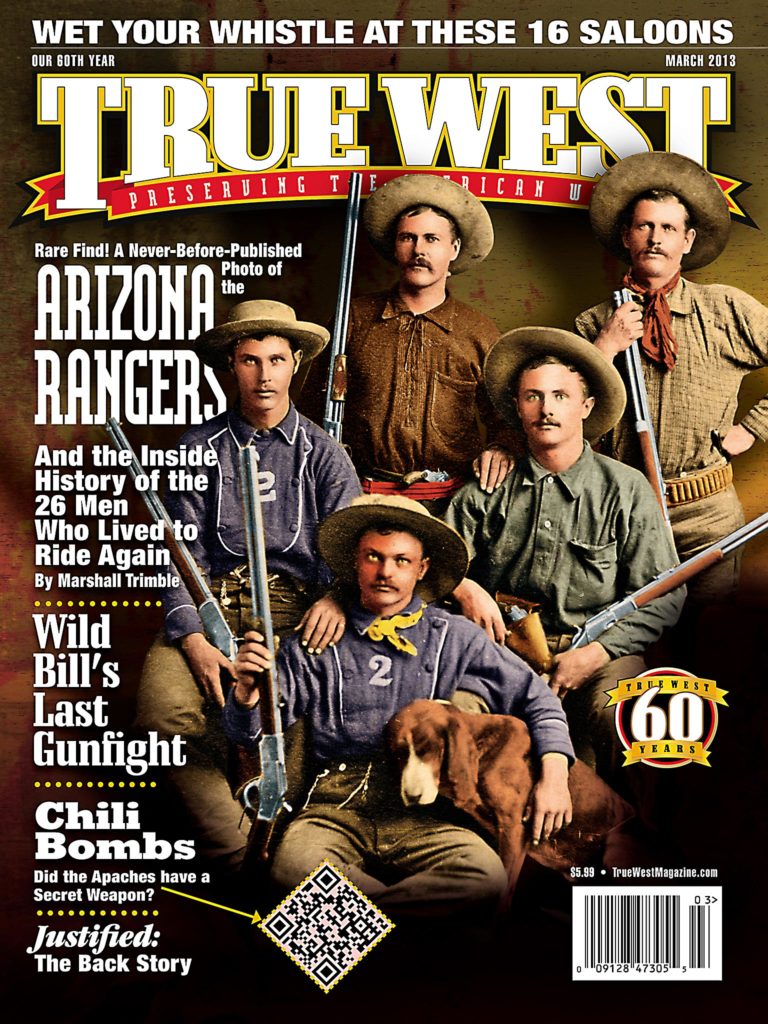

They were mostly colorful, hard-riding cowboys. Some were former soldiers with a natural ability to handle firearms. All were excellent horsemen, trackers and well-suited to take on the tough job against the Mexican border smugglers and large outlaw gangs that were still terrorizing the border country, even as the Old West was fading from reality into myth.

The governor’s first chore was to hire a leader. He needed a man with a proven ability to handle the task. He persuaded Burt Mossman to ramrod the outfit; Mossman was the former superintendent of the Aztec Land and Cattle Company, better known as the Hash Knife.

Using the old adage, “it takes a thief to catch a thief,” Mossman set about putting together a tough bunch of lawmen. Not that they were former outlaws themselves, but more than one likely had taken a step or two on the wrong side of the law.

During the next few years, the Arizona Rangers would be the darlings of the press. But the storied Arizona Rangers of 20th-century fame weren’t the first to bear the name Ranger in the territory.

Arizona’s First Rangers

Arizona’s first Ranger may have been one of the founders of Phoenix, Jack Swilling.

In 1858, he joined Arizona’s first gold strike on the Gila River, a few miles east of Yuma. Frequent Tonto Apache raids on the prospectors led to the forming of a militia called the Gila Rangers. The men elected Jack leader.

On January 7, 1860, while leading a punitive expedition against Apache Tonto raiders, Swilling and his Rangers came upon the Hassayampa River, previously unknown to white men. The area was too remote and dangerous to explore for gold, but Swilling would return at a later date. Meanwhile, new gold discoveries in the Pinos Altos region in May 1860 drew him to what is today western New Mexico.

That year, a group of citizens proposed creating an Arizona territory that included all of New Mexico, roughly south of the 32nd Parallel. Provisional governor, Dr. Lewis Owings of Mesilla, authorized the raising of Rangers to protect the settlers from bands of marauding Apache. The well-known frontiersman Jim Tevis, who spoke the Apache language, was ordered to raise the first of three companies of Arizona Rangers. He headed to the gold camp at Pinos Altos to recruit Rangers and to prospect.

The gold rush incurred the wrath of Mangas Coloradas and his Mimbres Apache who began attacking the prospectors and settlers. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the fighting between the North and South was of little relevance to the prospectors at Pinos Altos, who were busy defending themselves against the Apache.

Sherod Hunter, a rancher in the Mimbres Valley, joined the Arizona Rangers at Mesilla in May 1861. Shortly thereafter, military governor John Baylor appointed him captain and gave him orders to raise a company of Arizona Rangers for frontier defense.

On July 18, 1861, Swilling was appointed lieutenant of Capt. Tom Mastin’s Arizona Rangers at Pinos Altos. By August, Hunter, Tevis, Swilling and the Rangers had been mustered into the Confederate Army. The following February, the three officers led a 100-man cavalry into Tucson and raised the Confederate flag over the Old Pueblo.

The Confederates were driven out of Tucson a few months later. Many, including Hunter and Tevis, went back to Texas to join the fighting. Swilling, who had joined the Rangers to fight Apaches rather than Yanks, chose to remain. (He would later guide the famous mountain man Joe Walker back to the Hassayampa River, where they made a rich gold strike that brought about the founding of Prescott.)

Militia Rangers

During the years following the creation of the Arizona Territory in 1863 and the gold discoveries, the clashes between Indians and whites increased. Most of the violence took place along Lynx Creek, the Hassayampa, Verde, Gila and Salt Rivers and their tributaries. During those years, the Indians lived on the reservations and the whites occupied the land, but the times, they were a-changing.

A bill was introduced in the territorial legislature to raise a force of 100 Rangers—but it was defeated by one vote. The captains would have received $5 a day and the privates $3. The issue was money; the cost was prohibitive, $150,000 annually, while tax collection amounted to only $1,400.

Over the next few years, militia groups were organized at Wickenburg, Tucson and along the Gila River. These consisted mostly of Mexican, Pima and Maricopa Indian volunteers. They served and fought bravely for little pay. Despite their success, in the fall of 1866, they were disbanded. The raiding and depredations continued.

The call went out to raise another force of Rangers. A public meeting in Prescott on November 23, 1866, approved the raising of a company of 30 men to serve a three-month tour of duty. Tom Hodges, a local bartender and rough-hewn frontiersman, was named captain.

The Rangers immediately went on a campaign. In a savage battle near Prescott, they killed 23 Indians, including women, children and elderly. “Hurrah for the Yavapai County Rangers” reported The Prescott Miner, in praise of the carnage.

The campaign trail was long, tedious and dangerous. Enthusiasm evaporated quickly since the men were serving without remuneration. With the exception of a few punitive expeditions that were rarely successful, the citizens had to depend on the Army for protection.

Other groups of Rangers followed in the ensuing years. By April 1882, Gov. Frederick Tritle had authorized the first company of Rangers in Tombstone, with John H. Jackson as its captain. In May 1882, ex-Army Capt. Bill Ross, unhappy with the ineffective actions of the Army, organized the Tucson Rangers, some 50 hard-riding frontiersmen, to go on the offensive. Funded by local merchants, the Rangers had to subsist without the help of Apache guides. When they rode into Mexico, they were taken prisoner by the Mexican Army. They returned from the fiasco, unarmed, humiliated, weary and worn from their unauthorized raid across the border. Forced to ride some 300 miles through Apache-infested country, the resourceful captain had his men cut short poles and lay them across their saddle horns in a successful ruse to fool the Indians into believing they were armed.

On April 3, 1883, the citizens of Tombstone, goaded by the local press, declared they had no faith in the Army’s ability to contain the Apache and decided to raise a force of Rangers. Putting their faith in a “well-known scout” named Texas Charlie, who had seen lots of Apaches in the Sulphur Springs Valley, the force planned a punitive expedition to the San Carlos Indian Reservation. On their way north, the Tombstone Rangers met an Indian gathering mescal. They fired several shots in his general direction, fortunately missing their target. He fled north, and they fled back to Tombstone. Lieutenant Britton Davis wryly reported the Tombstone Rangers proved to be “of the same general character as the Globe Rangers and under the same….brand of stimulant.”

The Globe incident Lt. Davis referred to took place during the July 1882 Apache outbreak at Cibicue, when 11 men making up the “Globe Rangers” took to the field fully equipped with an ample supply of whiskey. Along the way, they stopped for a siesta and forgot to post guards. The stealthy Apaches slipped into their camp and ran off with all their horses. The Rangers were forced to sore foot it all the way back to Globe.

The 20th-Century Rangers

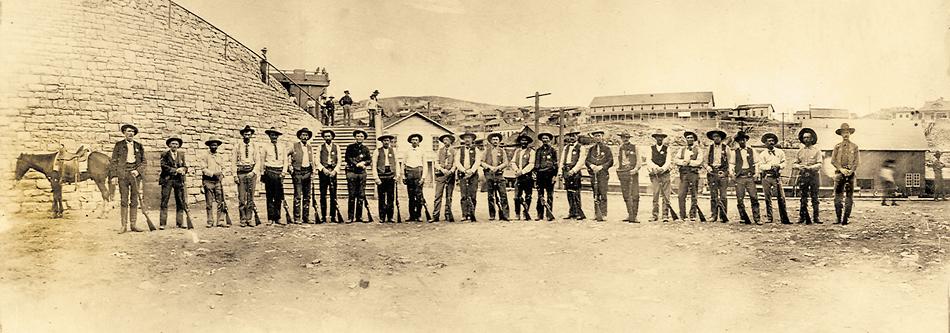

The new, improved 20th-century model Arizona Rangers under Capt. Mossman met their first challenge in 1901, when they locked horns with the notorious Bill Smith Gang in the rugged White Mountains. After Ranger Carlos Tafolla was treacherously murdered by the gang leader, Mossman and his men ran the gang to the ground, decimating their ranks until Smith left for other parts.

Mossman’s greatest personal victory was his daring pursuit and capture of Augustine Chacon, who once bragged he had killed more than 50 men.

Former Arizona Rough Rider Tom Rynning replaced Mossman as captain in 1902. He would lead the Rangers until 1907, when Harry Wheeler, rising through the ranks, took over. The colorful Wheeler was a bold, fearless man who killed four men in the line of duty. Famed Texas lawman Jeff Milton called him the best man with a gun he’d ever seen, and he’d seen some good ones, including John Wesley Hardin.

The last of the large outlaw gangs in Arizona met their demise in 1908, when a force of Rangers invaded their lair. The fight ended when Wheeler killed chieftain George Arnett in a gunfight.

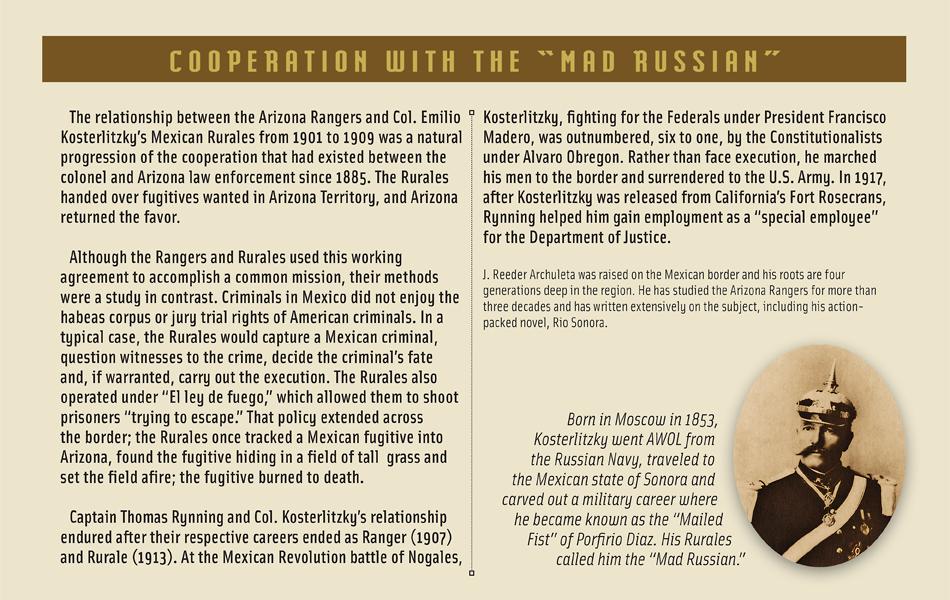

The Rangers also worked in close cooperation with Col. Emilio Kosterlitzky, the Russian-born head of the Mexican Rurales, to deal with smugglers and cattle rustlers. An outlaw on the run from the Rangers might think he was safe drinking with a pretty senorita in a Mexican cantina, then wake up the next morning in a Bisbee jail wondering how he got there. The girl had slipped a pill in his drink. Then one of Kosterlitzky’s men tied up the sleeping outlaw, slipped a gunny sack over his head and delivered him to a Ranger waiting on the other side of the border. The tactic worked well for both sides and relieved the officers of bureaucratic red tape.

Other times, however, relations between the Mexican border police and the Rangers had dire consequences.

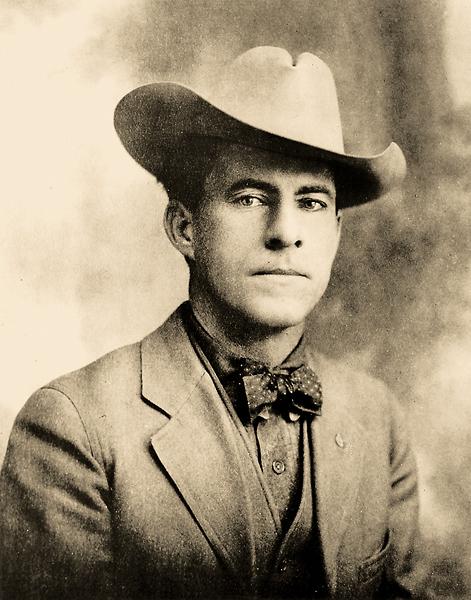

Besides Tafolla, Jeff Kidder was the only other Arizona Ranger killed in the line of duty. Author Robert DeArment rated him as one of the 12 most underrated gunfighters in the West.

Kidder joined the force in 1903. Packing a pearl-handled, nickel-plated Colt .45, he often worked alone on the Mexican border to control cattle rustlers and smugglers. He had a number of clashes with gun smugglers, and he was supposedly marked for death by the Mexican border police who were involved with the smugglers.

Kidder and three other Rangers were commissioned by Gen. Luis Torres, commander of Sonora’s northern district, to operate across the border. His reputation as a pistoleer along the border grew with each arrest he made; in 1908, he was promoted to sergeant. Kidder was also becoming a thorn in the side of the Mexican border police.

On the evening of April 4, 1908, Kidder slipped across the border at Naco to meet an informant. During an argument with a cantina girl whom he believed had picked his pocket, two Mexican cops burst in with pistols drawn and opened fire, knocking him to the floor. Kidder pulled his pistol and wounded both officers.

Bleeding badly, he struggled to his feet and tried to make his way to the American side, but he was blocked by Mexican line riders armed with Winchesters. A brief gunfight ensued. With his pistol empty, Kidder yelled, “All in.”

The officers pistol-whipped him as they dragged him to the local jail where they stole his valuables and refused medical aid. Kidder lived just long enough to tell his side of the story to Deputy U.S. Marshal John Foster.

After Kidder’s death on March 8, Gen. Torres ordered the Ranger’s body returned to the American side. However, no charges were filed against the officers who perpetrated the brutal murder of a fellow lawman.

Both Kidder’s and Tafolla’s names are etched on the marble walls at the Arizona Peace Officer Memorial in the plaza of the state capitol in Phoenix.

Partisan politics, not ruthless outlaw gangs, brought about the demise of the Rangers the following year. On February 15, 1909, the Rangers were disbanded for a number of reasons. Democrats accused them of supporting Republican candidates. Some counties resented being taxed while other counties were getting the most benefit from the Rangers.

The Old West was passing from reality into the realm of romance. Like the gunfighters who had tamed the cowtowns, the Rangers, too, had outlived their usefulness to a society that was looking ahead to statehood—a society that wanted no vexing reminders of its raucous past.

Marshall Trimble is the Official Arizona State Historian and the author of numerous Arizona history books. For further reading on the Arizona Rangers, he recommends The Arizona Rangers and Captain Harry Wheeler: Arizona Lawman, by Bill O’Neal, Arizona Rangers, by David DeSoucy, and The Conquest of Apacheria, by Dan Thrapp.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

– Courtesy Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography, VintagePhoto.com –

– Courtesy Carol Woolfolk –

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –