Ever heard of Elias Whitcomb?

Ever heard of Elias Whitcomb?

The Old West is full of brave Indian fighters who settled our country, yet never made dime novels or campfire songs. Whitcomb was one who escaped notoriety despite his outrageous exploits and tight links with notorious killers enshrined forever in books and films.

His pleasant presence might be what has kept him out of the annals of history. Said cattle baron and banker John Clay, “Somehow, amid the rougher side of life which you meet on the frontier, Whitcomb ever remained the innate gentleman.”

The man had plenty of opportunities to become larger than life. In 1857, at the age of 24, he left the plush life outside Boston to drive an ox team from Leavenworth, Kansas, to New Mexico Territory.

He figured one pair of shoes and one of boots would last him the nine-month round trip. Some pals bet him a new hat he’d need more. On his trip, Whitcomb loaned his boots to a friend, who lost one. Then his shoes gave out.

“To keep my word and win the bet, I concluded to walk barefoot from Ft. Union, New Mexico, to Leavenworth, Kan.,” he wrote later. “Behold me walking barefoot over prickly pears, stopping ever and anon to pull a pricker from my feet.”

A thousand-mile walk with no shoes—not so much for a new hat as to remain a man of his word.

Up in Smokeat Slade Station

Whitcomb also narrowly escaped becoming a casualty of one of the West’s most famous stage stops.

After a couple of years working for freighters to and from Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming, Whitcomb began trading with emigrants. In the spring of 1861, he moved his store to a station on the toughest portion of the Overland Stage route, between Fort Laramie and Salt Lake City—Horseshoe Creek Station, manned by Alfred “Jack” Slade.

The son of an Illinois congressman, Jack supposedly killed his first man at 13, although Slade biographer Dan Rottenberg has found no evidence to support this claim. Despite a drunken temper and penchant for gunslinging that would get him hanged by vigilantes just three years after moving to Horseshoe Creek, Jack was instrumental in opening the American West. He operated Horseshoe as a telegraph station and a stop on the Pony Express (William “Buffalo Bill” Cody claimed he rode for Jack in his youth). More important, he kept the Overland out of Confederate hands on the eve of and during the Civil War. He did this mostly by reputation; folks had heard he hanged horse thieves and stage robbers on sight.

“Never youth stared and shivered as I did when I heard them call him Slade!” wrote Mark Twain after an August 1861 visit to Horseshoe Creek Station.

In the winter of 1861, Jack’s mail agents massacred a family, leaving the children to die of exposure, because the father had allowed a former mail agent and suspected murderer to lodge at his road ranch. “[Jack] began to evince the demoniacal disposition which finally brought him to the gallows,” Whitcomb told his daughter in 1906.

But Whitcomb also saw the good in Jack, known as a faithful husband and decent man when sober. For instance, Jack adopted the five-year-old boy who, alone, survived the deaths of his other family members.

Jack liked Whitcomb. Often, he showed up at Whitcomb’s place to play cards and invariably drank too much. But not everyone was a fan of Whitcomb’s. “Mrs. Slade conceived the idea of getting me out of the way, for she thought that if Slade had to go farther for his whisky, she would have fewer quarrels with him,” Whitcomb recalled.

One night, while Jack was in Julesburg on business and his men were on a drinking spree, Jack’s wife, Virginia, told them to burn Whitcomb out. One broke away to warn Whitcomb; he and his savior barely made it out alive.

“My house was burned to the ground, I thus losing all of my earthly possessions, excepting a few horses and cattle which were grazing up the creek about 25 miles,” Whitcomb said.

The boys were so drunk and wild that they started for the haystacks, meaning to burn the station too. Horrified, Virginia grabbed a pistol and threatened to shoot the first man who approached.

Once the men sobered up, they were ashamed. Their leader tried to kill Jack as he came off the stagecoach, before he could be killed first.

Whitcomb had lost about $4,000 (roughly $100,000 today) as a result of the fire. Not only did he not exact revenge, but he took the rare high road.

Jack was “very indignant.” “[He] discharged every man who was implicated in the affair,” Whitcomb recalled. “I prevailed upon him to withdraw his order to discharge the men, as I considered their discharge would do me no good and do them much harm.” Jack retained his men, upon promises of good behavior. He never knew of his wife’s agency in the matter, unless his wife acknowledged it to him.

Battling Hostiles in Fort Collins

This kind of selfless decency, added to ridiculous courage, is also why a street in Fort Collins is named for Whitcomb.

He made his way to the Colorado post after a few years trading in Wyoming, belly-full of the mounting odds of being shot, scalped and mutilated.

The Indians killed five soldiers guarding the mail line at Piney Station and a sergeant at Medicine Bow, Whitcomb recalled of the increasing bloodshed in 1865.

The carnage forced the Overland Trail’s relocation from the North Platte River to a course along the South Platte in northern Colorado, formerly called the Cherokee Trail. Whitcomb moved, as well.

The Overland’s new mountain headquarters were on the banks of the Cache La Poudre River, which French-Canadian trappers had named two decades earlier. Six miles down river of today’s Laporte, the military reestablished Fort Collins after it flooded in 1864, just before Whitcomb moved to the area. Whitcomb was celebrated as one of the first residents. He claimed land on which he grew potatoes and cut wood to haul to Fort Laramie for the government.

In this first white settlement north of Denver, most of the fur trappers had American Indian wives. Whitcomb was no exception in the community. He had taken as his wife a teenaged half-Ogallala Sioux named Katherine Shaw. She bore him four daughters between 1863 and 1873. The first was just three years old in ’67 when they buried her in a still-existing grave near present-day Buckeye, Colorado.

It’s not hard to imagine how little Katya was killed. Indians commonly stole Whitcomb’s wagonload of potatoes en route to Fort Laramie, as well as any horses he dared keep around. They were so hostile that, in July 1868, he squired his family to Laporte for safety. Just one day after returning to his ranch in August, 18 warriors attacked as he and his men were cutting hay two miles up a canyon.

Whitcomb didn’t retreat; he gave chase. When an Indian shot his companion in the shoulder, Whitcomb loaded him on horseback and made a break for the ranch.

Cattle King’s Gentle Side

After the first Longhorns were driven up from Texas in 1866, Whitcomb ventured into the cattle trade. He took one of the first herds of Texas cattle into what became Wyoming Territory in the late 1860s; within a decade, he grazed thousands of cattle from east of Fort Collins to north of Cheyenne, Wyoming, where he moved in 1874.

Around him, pioneers were discarding their “squaws” and packing them off to the reservation. Whitcomb, ever the gentleman, offered his wife a choice. He would outfit her with ponies on which she and their children could return to her tribesmen, or she and the girls must ditch the moccasins and robes in exchange for white ways.

She spent one night away and then returned for the rest of her life. She and her two eldest daughters attended finishing school in Boston. She was allowed to keep a tipi in the yard of their Cheyenne mansion for her relatives when they visited.

Whitcomb was kind to her relatives, even going so far as to raise one who would grow up to become a famous Indian Wars scout. Around 1862, the Whitcombs took in eight-year-old Baptiste Garnier, the son of Katherine’s sister or cousin.

Known later as “Little Bat,” he was born at Fort Laramie around 1854 to a Sioux mother who died when he was eight. His French-Canadian father had been killed by Cheyennes in 1856.

Garnier stayed with the Whitcombs until he was 18, after which he became a U.S. cavalry scout. Frank Grouard, who guided with Little Bat on the Crook expedition of 1876, deemed him the most talented stock trailer and hunter the Rocky Mountains had ever seen. Those were rich words by Grouard, the scout who some believe brought about the Army’s killing of Lakota leader Crazy Horse.

After a Nebraska bartender brutally murdered Garnier in 1900, Garnier was lauded for “bringing peace to the frontier.” He was remembered for his honesty, which no doubt was honed by Whitcomb.

Oldest Range War Vigilante

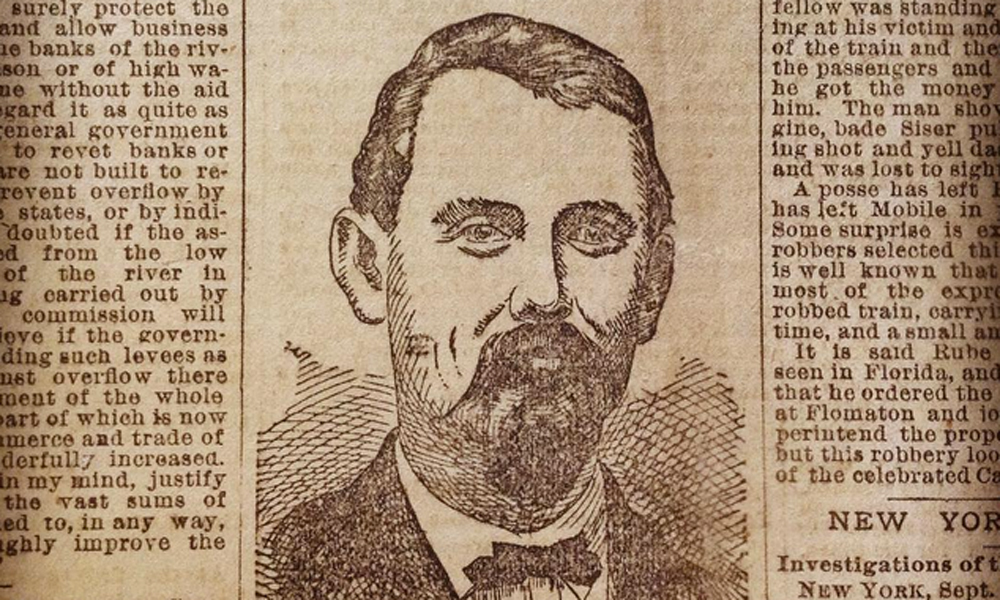

By the 1880s, Whitcomb’s reputation as a cattle baron led Wyoming’s most prominent stockmen to hire him as a stock detective. Working to eradicate “rustlers,” he became close to stock detective Joe Elliott, who called him “Uncle Whit,” and Tom Horn, who named his favorite horse “EW” after Whitcomb.

Not only did Whitcomb appreciate the considerable nerve of killers Horn and Elliott, but he saw them as the perfect gentlemen they sometimes were, just as he had Jack Slade. The big-hearted Horn apparently adored children, while Elliott was described as reserved, well-read and a respecter of law and authority.

To be sure, Whitcomb had his own contradictory personality. He was more than tolerant of frontier vigilantism, yet was an irrepressible spoiler of his three daughters. As they came of age in the late 1880s, he secured each girl her own large ranch along the Belle Fourche River.

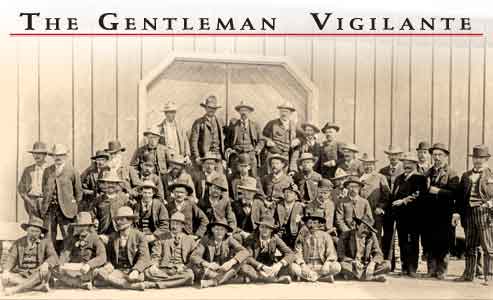

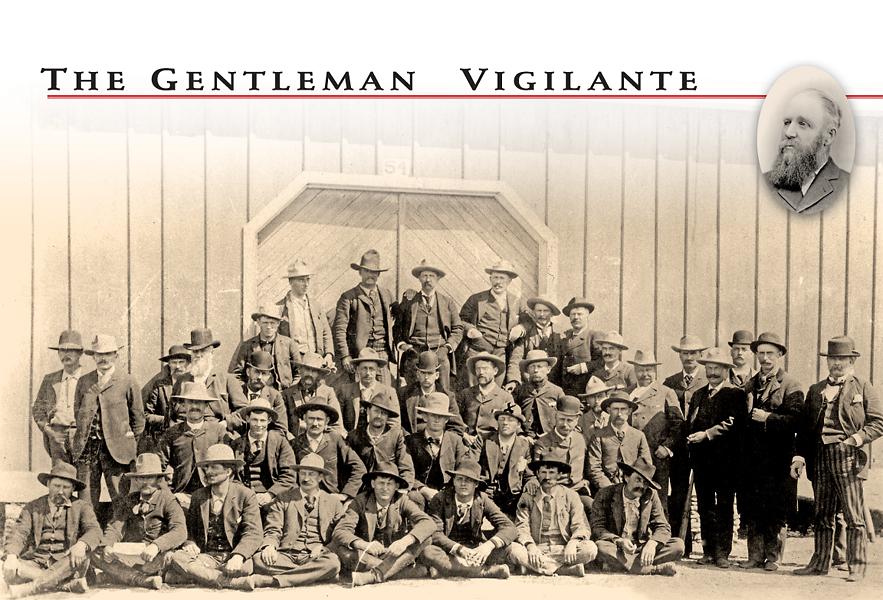

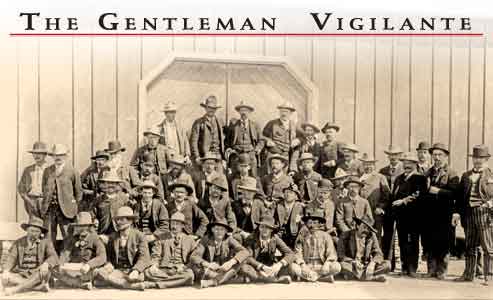

By 1892, his conviction was as strong as it had been on his long barefoot walk. Despite his gallant snow-white beard and age—nearly 60 years old—Whitcomb rode with the vigilante “invaders” of the Johnson County War a hundred miles through hunger and vicious snowstorms, intending to do away with stock rustlers.

Cattle baron Charles Oelrichs praised Whitcomb as an excellent horseman in his old age, riding “with a long stirrup and his back as straight as a ramrod.”

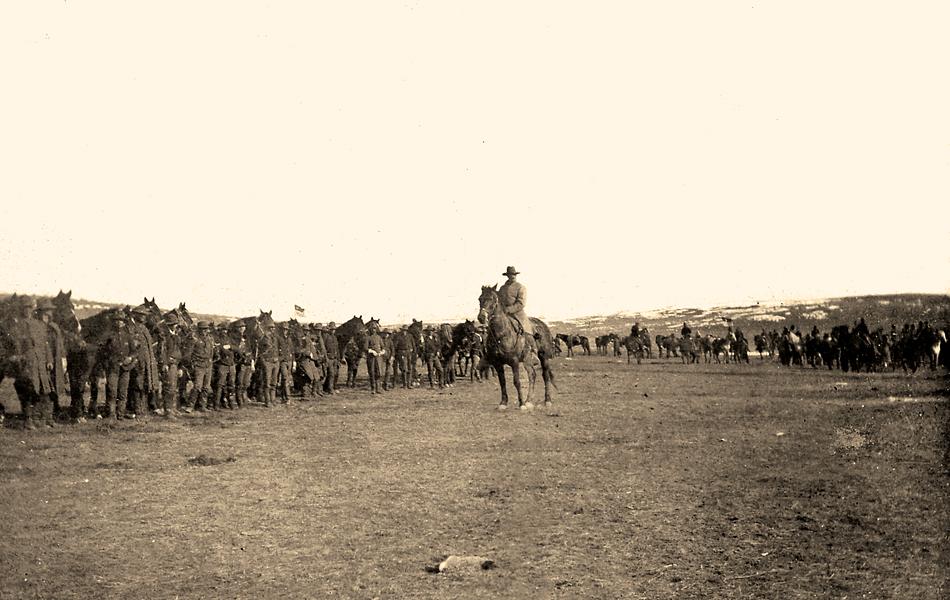

A sense of propriety had enticed Whitcomb to join in the Johnson County War; he simply couldn’t abide thieves. Even after the U.S. Cavalry captured him and the other cattlemen and jailed them at Fort D.A. Russell after they had killed cattle ranch lessees Nate Champion and Nick Rae, the people of Fort Collins sympathized with him.

“It would be extremely hard to convince the people of this county that he and the others were activated by unworthy motives,” reported The Fort Collins Courier, which deemed the war an “unfortunate expedition.”

End of the Trail

For the next several years, Whitcomb rode the range looking over his shoulder for retaliation. None ever came.

Nor did immortalization, except for a 1971 induction into the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum’s Hall of Great Westerners in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

To be fair, the Colt pistol Whitcomb carried in the Johnson County War brought $10,000 a few years ago when privately sold by his 84-year-old great-grandson. But that value was more about the infamous range war than the oldest gentleman who fought in it.

Perhaps the lack of notoriety could be attributed to the cattle baron’s mild mannerisms. A neighbor once wrote of Whitcomb, “He was just the opposite of what one would expect in a man who had battled all the elements of those rugged times. Not loud, profane, coarse or boastful.”

Or maybe folks abided by his wish, to close his eyes in their last long sleep, “content to be forgotten by the generations yet to come.”

Ironically, Whitcomb’s life ended with the kind of flourish he never invited, but fully embodied. At 81, the horseback gentleman was struck dead by lightning while rounding up bulls on his Wyoming ranch. He was reportedly buried astride his horse in a true Sioux-style funeral in 1915.

A graduate of the University of Wyoming, Julie Mankin discovered E.W. Whitcomb’s story while reporting on Wyoming’s historic ranches for The Gillette News Record.

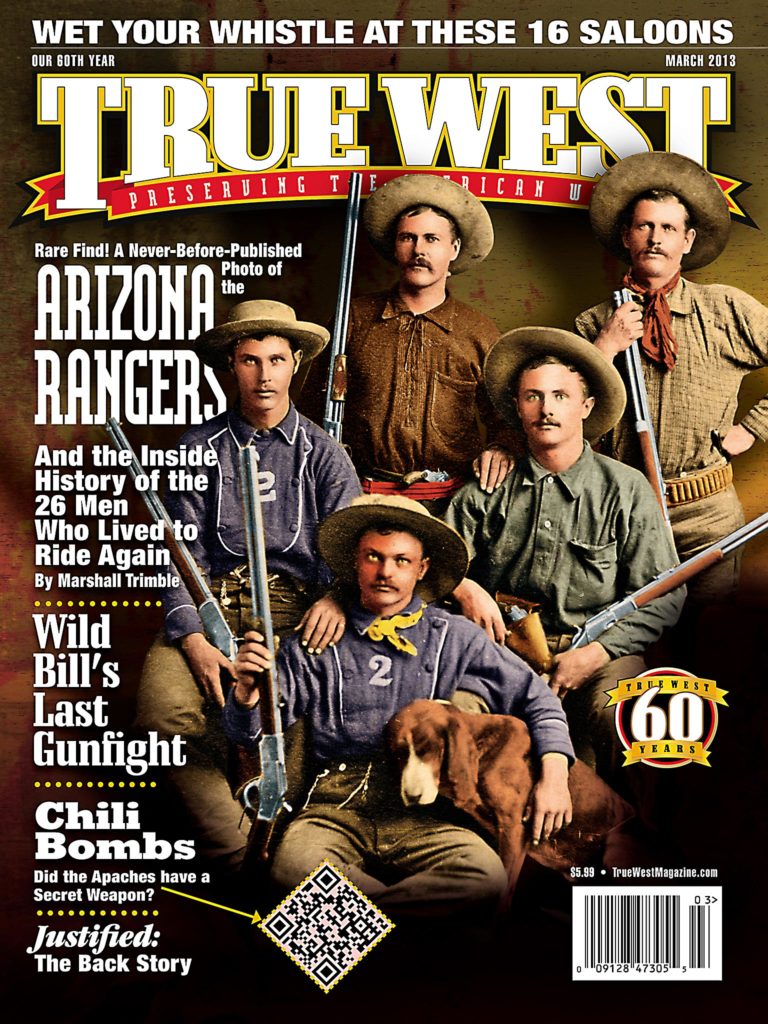

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Fort Collins Museum of Discovery; Katherine illustration courtesy Wyoming State Archives Neg. 14968 –

– Courtesy Wyoming State Archives: Johnson County War Invaders Neg. 9516; Whitcomb inset Neg. 24616 –

– Courtesy Wyoming State Archives Neg. 21993 –

– Courtesy Fort Laramie NHS –