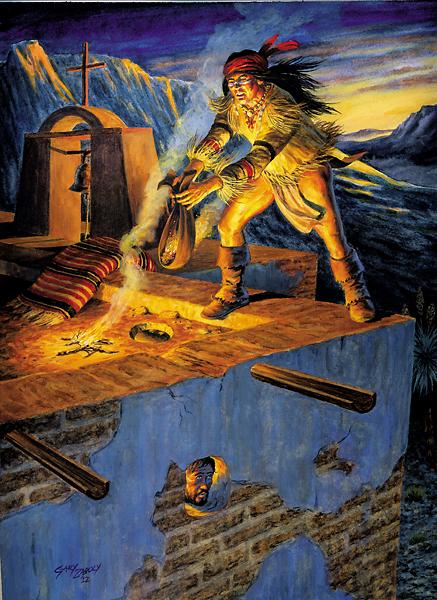

Geronimo’s segundo and half brother, the warrior known as Fun, climbed stealthily to the earthen roof of the iglesia (church).

Geronimo’s segundo and half brother, the warrior known as Fun, climbed stealthily to the earthen roof of the iglesia (church).

Kaytennae had already knifed to death the Mexican standing guard at the adobe. The others, mostly Chiricahua and Bedonkahe, were waiting in the darkness until finally, the community of hated miners all gathered within the confines of the small adobe. The Apaches got to work, barricading the entrances with heavy logs and rocks.

Now came the most important part of their daring plan, for which any mistake meant death to the captive women and children they were attempting to rescue. They waited silently, desperately, until Fun’s work was completed so they could execute the second part.

Fun had cleverly ground hot chili pods, to which he added a flammable shaved wood mixed with pine sap (ocote). Taking the pods from his heavy buckskin shirt, Fun rubbed fire sticks against the lethal mix and quickly lit a fire. He let it smolder a moment; then he dropped it into the barricaded building from a hole he had dug earlier. After he covered the opening with a blanket, Fun slipped back into the shadows.

The crowded miners panicked as they tried to break their way out of the smoky structure. The chili smoke bomb acted much like today’s tear gas used to control crowds or pepper spray used to create chaos; it gave off toxic, choking, burning smoke and a penetrating chili smell that destroys the nose membranes.

As confusion reigned, the Apaches quietly and methodically killed the guards by the adobe compound where their families were imprisoned. They also stole supplies and ammunition, plus leather bags of gold and silver that had already been packed for a mule pack train trip to Chihuahua City.

Heading to Juh’s stronghold at the top of the zigzag trail near Blue Mountain, the Apaches felt much relief. Though they had lost two valiant men in the attack, they knew that a great celebration would occur because of this daring escapade.

This had been a rescue like no other. During the final years of the Indian Wars, the Apache normally had to be alert at all times. Yet this was not “hit and run,” as were most of their strikes. The strategy had required observation, planning and timing. No Mexicans would dare follow the Apaches into their lair at the top of the Blue Mountain. The bleached and broken skeletal remains at the bottom of the trail were proof that no one could breach the stronghold; Juh had his watchful guards cast planted boulders upon any trespassers or rain down arrows on any who looked like they might survive the first onslaught.

The Apaches had spent weeks searching for the women and children, brutally kidnapped while out gathering mescal. When scouts brought word that the women and children

were working in the mines lugging

loads of ore and rock, vengeance was the only thought that boiled up in their angry minds.

No man could stand to see his women and children crowded into corrals or sent off as slaves or to fates even worse than death. No warrior people would accept this terrible scenario, and the Apaches were no different.

The Apaches found a way to communicate to the captives that help was to come, soon, so that they would not starve themselves. Facing slavery was worse than death, so the women usually refused to eat.

While the scouts observed the site where their loved ones were being held captive, they noted that, on the seventh day of the week, all the people but the guard went inside an adobe structure in the town square.

For this daring raid, the Apaches turned to a clever weapon within their war chest. The chili smoke bomb might sound benign, but if you have ever roasted and peeled green chili or red peppers, and gotten the smoke or even the smell in your nose, then you know that, Wow, sometimes it can bite!

Chili has been used for centuries in all parts of the world. The Aztecs and Peruvian Indians used the burning and blinding smoke as a weapon. Today, India’s government military establishment still uses hot chili peppers to stop elephants from entering communities, and as crowd control or a method to

fight terrorism.

The chili bomb thrown by the Apaches was not the last threat to this village. After the dramatic rescue, deliberate rock and earth slides totally destroyed the hated pueblo. Some believe the mountain village was Lost Tayopa, a gold and silver mining community hidden within the rugged barrancas of the Sierra Madre that to this day has never been relocated. Spanish documents and Jesuit maps indicated the former richness of the region. Slaves were always needed to do the heavy work and to run the creaking ore arrastras.

Adventure-driven people have combed the Sierra Madre in search of this famed series of mines to no avail. When asked, the Apaches did not know the name of the pueblo, only that it no longer existed.

Tragically, where the Apaches had once held sway over a vast array of desert and mountain lands, the hated Mexicans and whites were developing mining communities throughout the mineral rich mountains. Above all else, the Apache held great disdain for miners because they grubbed in the bowels of Mother Earth for the yellow and silver iron. Gold was sacred to their god, Ussen; it was unacceptable to use, except in dire times.

The rescue might have been lost to history, if not for the Apaches’ ancient oral history tradition. Juh asked Warm Springs Chief Nana to relate the story around campfires, most memorably for that first celebratory occasion in Juh’s stronghold. He declined, and Geronimo, instead, described the bravery of Fun, Kaytennae and Martine.

One of those present at the victory celebration was Ace Daklugie, son of Juh and nephew of Geronimo. He was among the surviving prisoners of war who made it back to New Mexico in 1913. During the early winter months of 1955, just prior to his death, he related the chili bomb raid to famed author Eve Ball.

Back in Juh’s stronghold, the Apaches felt vengeance had been delivered. Though they had lost two in the daring rescue, the women and children’s shining and happy faces that night were reward enough.

Lynda Sánchez, of Lincoln, New Mexico, has been to Juh’s Stronghold in the Blue Mountains. A member of Western Writers of America, she has written four books and she contributes to New Mexico Magazine, Arizona Highways and True West.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection; inset True West Archives –

– Illustrated by Gary Zaboly –