True West Magazine’s annual award given to towns that have made an important contribution to preserving their pasts and to sharing their town’s historical relevance to our nation.

True West Magazine’s annual award given to towns that have made an important contribution to preserving their pasts and to sharing their town’s historical relevance to our nation.

10. GRAPEVINE, TX

“We’ve got two gunfighters. Y’all want to buy them?” Mayor William D. Tate asked the Grapevine City Council last summer.

The mayor had just finished his pitch for a gunfight re-enactment that would take place every day at noon and 6 p.m. to draw people to downtown during mealtimes. Usually a proposal to host gunfights would not be surprising for a historic Western town, but this one had a twist: the train robbers would be animated. Even more, only the computer designed by LifeFormations of Bowling Green, Ohio, would determine whether Sam Bass or the other robber bit the bullet, as they shot it out in the 120-foot clock tower being built for the new Convention & Visitors Bureau.

We won’t find out until this year if these robot gunfighters make a bang with Grapevine’s 50,000 residents and its visitors, but the quaint town has proved its charms in other ways.

The 1859 farm started by Thomas Jefferson Nash is still the place to go to learn about beekeeping and hand cranking ice cream. But the acquisition last year of two buildings may allow the Grapevine Heritage Foundation to keep the farm open five days a week. The soil conservation building and 1890s Estill cottage could provide the 5.2-acre farm the entryway it needs to control access. Kudos to David Kemplin, the city’s historic restoration coordinator, for stepping in to save the petite, 732-square-foot cottage from the wrecking ball.

The biggest change was the more than $1-million restoration of the former offices of the Grapevine Sun newspaper, which 19-year-old Benjamin R. Wall had started in 1895. With its welcoming brick parapet, the 1897 building restored by Phil Berkebile is now home to the only art gallery in Texas that focuses exclusively on Western Art. Hanging on the walls of the Great American West Gallery these days are works by Bill Anton, Martin Grelle and Roy Anderson.

One of the best parts about living here is that residents can head southwest to Fort Worth in true Victorian style, via the Grapevine Vintage Railroad, with its operational diesel and 1896 steam locomotives.

With the cattle drive at Stockyards Station a train hop away, folks might make it back home in time to catch the 6 o’clock robot gunfight.

9. BISMARCK, ND

At Sandbag Central, on Tuesday, May 31, 2011, a 40-mph-plus gusting wind chilled the 52-degree air around 16-year-old Bismarck High School student Liz Mizell. Shoveling next to Mizell were 43-year-old Waylon Hedegaard and his 13-year-old son Reilly; these two had been filling 30-pound sandbags in eight-hour shifts, seven days running. Their home by the Capitol was safe, yet both felt they had to pitch in. “This is our community,” Hedegaard, a union boilermaker, who took a vacation to work at the site, told The Bismarck Tribune. “We strongly believe it’s time to pull together.”

He was right. The Missouri River was on its way. Time was just about up.

The next day, for the first time since Garrison Dam was built in 1953, the dam’s spillway gates opened to release water from the bulging Lake Sakakawea, which had risen precipitously due to Montana rainfall. Just a few days earlier, the residents of Bismarck, North Dakota, had found out that the Missouri was expected to crest to 20 feet—four feet above flood stage.

For hundreds of Bismarck homeowners, and thousands of others in the region, a rushing river of tears was spilling out of those gates.

Bismarck’s neighbors along the Missouri also raced against time to fight this onslaught of water. Staff emptied Fort Mandan of its guns, uniforms and buffalo robes, while sculptor Tom Neary moved his 1,400-pound steel canine, Seaman, away from the riverbank to rest by the steel feet of Lewis & Clark.

Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park closed, postponing its Custer celebration to August. Its Lewis & Clark Riverboat did not make any trips down the Missouri. By November, the boat was still stuck in a sandbar and the foundation was trying to recoup its lost $375,000 revenue by scheduling 2012 cruise reservations for earlier than usual. The foundation fears it may not survive.

As water ravished destruction all around him and beyond on one June day, Mark Armstrong, the Burleigh County commissioner, stood on the shore of Bismarck’s Centennial Beach, filming the latest victim: a building floundering in the river. It was the 1911 Northern Pacific Railroad depot, which former Mayor “Hawk” Haakenson had moved to these shores from nearby Wilton. It later became Captain Meriwether’s Landing Restaurant, serving food to folks taking a trip on the Lewis & Clark Riverboat. The restaurant had been out of business for about three years.

Armstrong kept his camera aimed at the depot, as the Mighty Mo thrashed against it. Not all history can be saved. But one Bismarck man still took the time to pay his tribute.

8. DODGE CITY, KS

Dodge City knows how to get you out of a rut.

It’s no secret that this Kansas town is home to the longest clearly identifiable section of the Santa Fe Trail, but now visitors can truly grasp the context of what they are seeing as they stare out at the deep gouges cutting this vast prairie.

Updated and new signs at the ruts help visitors make the choice Santa Fe traders did: should we travel the Mountain Route (and view sites such as Bent’s Old Fort) or the Cimarron Route (and visit sites like McNees Crossing, in New Mexico, then Mexico)? Another sign shares Dodge City area trail sites, such as the 100th Meridian Marker and the 1865 Fort Dodge.

Santa Fe Trail Association President Jim Sherer and Boot Hill Museum Director Lara Brehm were on hand for the unveiling of their pride and joy last September. Fittingly, the first people to visit the new ruts exhibit were trail enthusiasts in town for the Santa Fe Trail Symposium.

Yet Dodge City certainly was not in a rut last year. The town’s 28,500 residents and its visitors had plenty of Old West events to attend (who could miss a Bull Fry?). They also got healthy helpings of Harvey Girl history at the Santa Fe Depot from author Steve Fried, and of the 1878 “drive-by” shooting of Dodge City’s saloon singer Dora Hand from authors Chris Enss & Howard Kazanjian.

Coming soon to Dodge: a life-sized statue of Doc Holliday at a card table, with three empty seats, to give folks a fun photo opportunity. He’ll join the statue of Wyatt Earp, who the dentist helped defend from some bloodthirsty cowboys, thus cementing their lifelong friendship.

7. ST. LOUIS, MO

Everyone knows why St. Louis is the nation’s Gateway to the West (Cliff Notes version: it’s where Lewis & Clark began the nation’s first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast).

But in 2011, this city reminded us why St. Louis is also Baseball’s Gateway to the West. In October, two brilliant batches of baseball games were played. The first, on October 15, took place beneath the Gateway Arch, home to the impressive Museum of Westward Expansion.

Wearing bib front shirts with a large U, the Union nine utterly destroyed its competitors. One match was close (Unions got 7 against the Brown Stockings’ 6), but the other one was brutal: Unions scored 19 runs against the Perfectos’ 5. Shawn “Pebbles” Beach topped them all with his four runs, while Jim “Noodles” Stockglausner followed with three. By the end of the game, every Union player had scored at least one run.

The Union vintage base ball team takes its name from the Union team that played here as early as 1860. Merritt W. Griswold, who had moved to St. Louis the year before, started up what most credit as the city’s first ball club, the Cyclones. The July 9, 1860, match at Lafayette Park between the Cyclones and the Morning Stars is said to be the first match game played west of the Mississippi River according to the rules of the National Association.

One member of his Cyclones team, Frederick Benteen, would even teach baseball to his 7th Cavalry troops, which is how Gen. George Custer ended up watching ball games while touring the Black Hills in 1874. Fast forward to 2011, and the Cyclones are still playing at Lafayette Park.

Two other vintage ball teams playing St. Louis these days are the Brown Stockings, founded in 1875, and the Perfectos, founded in 1899. Actually, historically, the Perfectos used to be the Brown Stockings. When owner Chris von der Ahe’s ballpark burned down during an April 1898 game with Chicago, he lost the team to the Robison brothers, who owned the Cleveland Blues. The brothers changed the name of the St. Louis team to the Perfectos and switched the team’s brown color to red. In 1900, the players earned a new nickname: Cardinals.

Fast forward to 2011 and the next big batch of games in October: the Cardinals play a seven-game stretch against the Texas Rangers and win their 11th World Series.

St. Louis is truly a town that celebrates its heritage—even when it comes to baseball.

6. SANTA BARBARA, CA

At the Santa Barbara Courthouse, Laurie Rasmussen’s harp processional bounces joyously off the terra cotta floor tiles as she plays Felix Mendelssohn’s “Wedding March.” About 75 wedding guests chat happily beneath 1,000-pound wrought-iron chandeliers, a hand stenciled ceiling and the room’s showstopping mural: 6,700 square feet of Spanish Colonial history hand painted by Dan Sayre Groesbeck, from Vizcaino’s visit to the coast in 1602 to John C. Fremont’s 1846 journey over San Marcos Pass.

Yet a fire in the courthouse attic in January 2010 almost put a halt to the pairs of lovers who wanted to proclaim their love for each other amid such majesty. Smoke was causing acid to continually burn holes into the mural’s unvarnished paint. Patty West and her team at the South Coast Fine Arts Conservation Center took up the job to remove the smoke and restore the mural. By the time 2011 rolled around, wedding bells were ringing.

Santa Barbara certainly has a love for its art. Take Ellen Durham, who runs Santa Barbara Walking Tours. She shares the stories of public artworks, like Lori Ann David’s Syuxtun Story Circle, while also pointing out hidden gems, such as the sign marking the 1861-1901 stagecoach stop.

Even the Chumash Indians who lived here from the 1300s-1800s were artists. Their red-and-black pictographs are vividly splashed against canyon walls at Painted Cave park.

The town’s Spanish Colonial charm extends from its art to 1830s La Huerta-style landscaping by Jerry Sortomme to the 1782 El Presidio de Santa Barbara. The last military outpost built by Spain in the New World is interpreted and operated by the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation, a 1963 nonprofit honored in 2011 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The nonprofit recently acquired the last remnant of the city’s Chinatown, Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens. Its next major project is working with the California State Parks to develop the Santa Ines Mission Mills— two 1820s fulling and grist mills—near the town of Solvang.

The most festive and fun reminder of the town’s rich heritage came during last year’s 225th anniversary of the Santa Barbara Mission. Back at the courthouse, in the August heat of the sunken gardens, young and old twirled around in bright folklorico dresses and decorative shawls for Old Spanish Days, dancing and singing to songs from the city’s pastoral era.

5. RUIDOSO, NM

Fourteen years have passed since cowboy picker Ray Reed showed up in his Winnebago at the Ruidoso Downs Race Track in Ruidoso, New Mexico. Although this cowboy from a pioneer New Mexico family died in 1998, his legacy lives on in the Lincoln County Cowboy Symposium.

The heritage celebration might not be what it is today without Gene Hensley’s request for help promoting his racetrack. Ray drove from ranch to ranch to recruit horses for a quarter horse race, the All American Futurity that is still held at the tracks every Labor Day.

Then in 1989, Ray performed at the first National Cowboy Symposium in Lubbock, Texas. He was so energized by the experience that he wanted to bring the celebration of cowboy life to Lincoln County, immersing it with the stories of outlaw Billy the Kid, cattleman John Chishum and the Lincoln County War. He came up with the idea to celebrate the region’s various cultures with cowboy musicians, Hispanic mariachi bands and Mescalero Apache singers and dancers. And, like everyone knows, the way to a cowboy’s heart is through his stomach, so he topped it all off with a chuckwagon contest.

The festival grew so big, it outgrew the Glencoe Rural Events Center, where it was first held in 1990. As the owner of a large race track, Hensley paid tribute to his old friend by moving the celebration to his track in Ruidoso. Come October, cowboy culture just bursts at the seams there with 23,000 people; event organizer Sunny Hirschfeld admits attendance for the past few years is “pretty much the max we can hold at the facility. We are full up.”

Out of Ray’s dream to celebrate cowboy life has come many other great treasures for Ruidoso. The stories of Billy the Kid and his ties to Lincoln County are shared at the Ruidoso River Museum. The region’s Indian, Hispanic and pioneer cowboy cultures are all showcased at the Hubbard Museum of the American West. The local SASS club dubs itself the Lincoln County Regulators, after the deputized cowboy posse that wanted to avenge the 1878 death of rancher John Tunstall. Ruidoso has clearly earned its spot among the Billy the Kid towns, like Lincoln, featured on the Billy the Kid National Scenic Byway.

And you might just hear some Western swing tunes from Ray’s old friends, Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, playing on W105. For nearly a decade, Joe Baker has been keeping Western Swing on the forefront, during his weekly Backforty Bunkhouse Show.

4. OKLAHOMA CITY, OK

On a sloping Montana meadow, with a backdrop of the flat-topped Square Butte that Charlie Russell had replicated with his paint strokes, some serious museum honchos were huddled inside a canvas tent, forging a deal with a tight-knit group of cowboy artists.

Then they had to strap on some guns, jump on horseback and screw on their courage. After convincing the Cowboy Artists of America to return home to Oklahoma City, the museum honchos knew they could take on a cowboy mounted shooting contest. They had already shot high and scored a big win for the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Craig Clemons, chief development officer, Leslie Baker, director of marketing, and Jo Dahl Creech, executive administrative assistant, returned to OKC with the best prize that came out of the June trail ride, which the Cowboy Artists hosted at Mike and Sheila Ingram’s Bell Cross Ranch in Cascade.

After the National Cowboy Hall of Fame had opened in June 1965, Joe Beeler, whose works were presented in the museum’s first one-man exhibition, convinced Dean Krakel and art director Jim Boren to also host the Cowboy Artists of America. Beeler had just formed the group with Charlie Dye, John Hampton and George Phippen. The museum agreed, and the first show opened on September 9, 1966.

For their eighth exhibit, the artists broke away from the museum to host the show at the Phoenix Art Museum in Arizona.

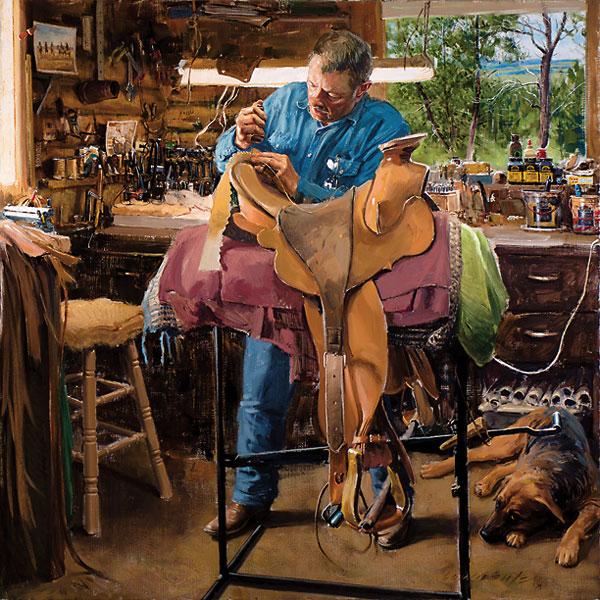

In 2011, after nearly 40 years in Phoenix, the Cowboy Artists returned home to the impressive institution now known as the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Yet the museum did more than bring this 22-member group back; it combined forces with the Traditional Cowboy Arts Association to create a joint exhibition, “Cowboy Crossings,” in October. This meant that Pedro Pedrini’s take on an 1850s California don’s saddle mingled with Loren Entz’s oil painting, Bill Allison, Saddle Maker, Roundup, Montana (which took the gold for that category and was featured on the event poster; see photo). The inaugural event brought in more than $2.2 million in sales.

Cowboy culture of the American West has always been the museum’s strong point; by returning to its roots, the museum has lifted itself up to the next level. Oklahoma City is certainly the happier for it. Even The Wall Street Journal took note last year of the $45.7 million positive economic impact the museum brings to Oklahoma City each year.

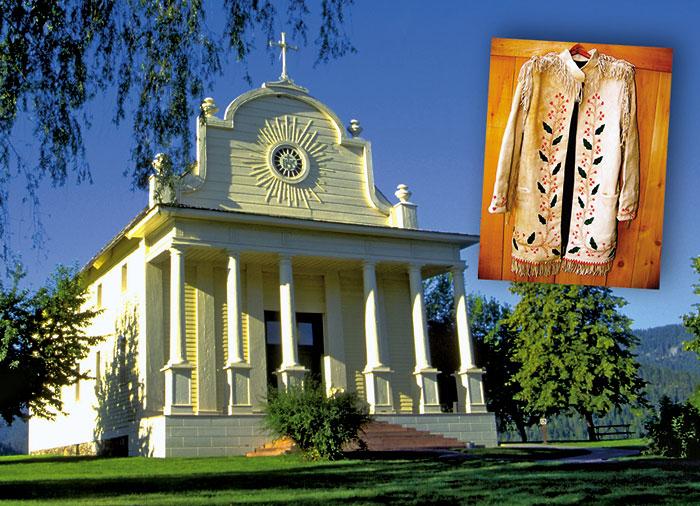

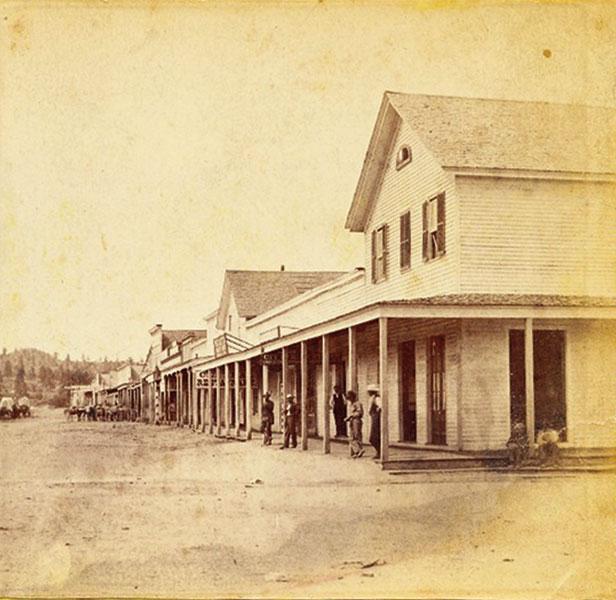

3. COEUR D’ALENE, ID

Along a rocky shoreline of Coeur d’Alene Lake, young couples, teenagers and matronly ladies walk their dogs, while pygmy nuthatch songbirds run head-first down Douglas-fir trunks.

German immigrant Tony A. Tubbs might not have foreseen that Coeur d’Alene, Idaho’s 46,000 residents would find this rock peninsula a haven for their 17,000 dogs, but he did have a love of sharing Tubbs Hill with his neighbors. After he came here in 1882 to file a gold claim, he opened the south side for the public to enjoy; it certainly is a friendly, hospitable spot these days.

Northwest of Tubbs is a floating boardwalk, where steamboats once docked to transport gold miners and supplies. You might think you’re seeing the ghost of a steamboat captain when a white-bearded man, clad in a blue coat and a captain’s hat, passes by you downtown. You’re not. His name is Robert Singletary, and he is the town’s walking treasure.

To mark the 150th anniversary of the Mullan Road, this past July, the former music and history instructor at North Idaho College led a hike along a portion of the 1859 wagon road that stretched from Walla Walla, Washington, to Fort Benton, Montana; the group ended up at Fourth of July Pass, where Mullan and his men had etched into a white pine: “M.R. July 4, 1861” (the stump is on display at the Museum of North Idaho).

But history tours are not limited to anniversaries; last year, Singletary brought back his guided bus tours to historic sites in Silver Valley and Coeur d’Alene. Among those sites is the Cataldo Mission, Idaho’s oldest building, where Singletary educates his guests on Jesuit Father DeSmet’s fateful meeting with the Coeur d’Alene Tribe.

Now, the Coeur d’Alene Indians are sharing their own stories of DeSmet; last year, they found a permanent home for their $3.26 million project, “Sacred Encounters,” at the 1853 mission. The 50,000-square-foot exhibit showcases videotaped interviews with tribal elders, a letter by DeSmet, century-old dolls made by the tribe and even a re-creation of the mission on Christmas Eve 1842.

Back in Coeur d’Alene, Singletary can also bring Fort Sherman to life. Dressed in a heavy wool colonel’s uniform, he shares the history of this 1877 fort abandoned by the Army after troops were sent to fight in the 1898 Spanish-American War. Three of the fort’s buildings still stand: the chapel, the officers quarters and the powder magazine. North Idaho College is presently renovating the interior of the brick powder magazine.

In Coeur d’Alene, history does not go to the dogs. Although you might find some Labradors trotting by on a few of the historic trails.

2. LEADVILLE, CO

The grueling climb up Columbine Mine, which tops out at 12,570 feet, is on the bucket list for the toughest mountain bikers. Olympic gold medalist Lance Armstrong even admits he rediscovered his love of long days on a bike while competing in the Leadville 100.

You see, Leadville has a knack for capitalizing on its riches. Yet the 10,000-feet-high town puts its highest aims at celebrating the silver and gold riches that founded it.

The town’s love for its breathtaking environment and its mining heritage can make for a happy marriage. When 29-year-old Kathleen Gouldy of Alisa Viejo, California, and her boyfriend Tom Wallis competed this past August in the bike race, their home away from home was the majestic Delaware Hotel. The 1886 downtown hotel had been celebrating its 125th-birthday all summer: fast draw competitions, a Molly Brown weekend, Victorian teas and discussions about Leadville’s legendary characters, like Silver King Horace Tabor who died penniless in 1899.

But like in any marriage, complications can arise. Leadville, itself, has been on quite a climb. Since 1983, citizens have been battling the Environmental Protection Agency in a fight to maintain the historical character of their home. But this town has survived booms and busts, and the 2,740 folks who live here know how to persevere. One of their biggest accomplishments is a trail that doesn’t usually make the national news: the 12.5-mile paved Mineral Belt Trail, which parallels California Gulch, the site of the city’s first gold strike. You can see the old Tabor General Store, mining tails jutting out from the road and dilapidated mining buildings sticking up against the Sawatch range of the Rocky Mountains. Conceived in 1994 and dedicated in 2000, this silver thread now binds the mining heritage that is at the core of Leadville.

This past September, the EPA gave the town good news. The community’s efforts on the California Gulch (and we mean community, everyone pitched in here) has been a success for the residential areas of Leadville.

Although some battles were won and lost here that not everyone is happy about, Leadville has fought the good fight to preserve its history. Through it all, the town has never forgotten its true riches. In 2011 alone, their focus on history was evident with the renovations of the Delaware Hotel and the 1878 Healy House (next to the log cabin of one of Colorado’s first millionaires). Colorado Mountain College’s local campus offers a preservation degree with hands-on experience restoring the 1872 Hayden Ranch. Tabor Opera House is working to restore its theater sets dating back to 1879, even while it entertains with musical performances and Silver Boom lectures. And every March, horse and rider teams still pull skiers down Harrison Avenue, like the cowboys who started the tradition in 1949.

Best of all, no matter where you are in Leadville, most of the buildings you see were built between 1880 and 1905. Even a simple stroll puts you back in the Victorian era.

#1 TOWN OF THE YEAR

PRESCOTT, ARIZONA

“There is something better than making a living—making a life.”

Sharlot Hall wrote those words on the opening leaf of the diary she carried during her 1911 trip to the Arizona Strip, which Utah wanted to annex.

Both the sheriff and the stockman warned her, “Don’t go.” They had no guidance to offer about the roads, water or lay of the country. But Sharlot was determined to find that “stray history, no matter how hard it might be to round up,” so she hired guide Al Doyle in Flagstaff and set off.

“We carried grain for the horses for a month, a water barrel to tide us over the desert stretches which we were told might be long, and the lightest camp outfit that it seemed possible to get on with,” wrote Sharlot, on what had to be one hot July day.

She was not about to let rough roads keep her from collecting the stories of Arizona’s mining camps and towns. After all, the people had trusted her with an important duty by electing her Territorial Historian of Arizona in 1909, making her the first woman to hold public office in Arizona.

The stories and pictures and artifacts Sharlot gathered over the years would inspire her to open up a museum in Prescott in 1928; the Sharlot Hall Museum remains the heart of this town, which was founded as Arizona’s territorial capital the year after an 1863 gold rush.

We don’t doubt that Sharlot’s heart would have been warmed by the fact that 100 years after statehood, Prescott owes much of the past decade’s efforts to preserve the town’s history to yet another woman: Nancy Burgess.

In fact, the museum’s director, John Langellier, presented her the town’s highest honor, the Sharlot Hall Award, at a dinner held last August for the Western History Symposium at Hotel St. Michael.

Now retired from her post, the former interior designer and paralegal was hired in 1991 to serve as Prescott’s historic preservation specialist. During her tenure, she documented more than 700 buildings, sites and objects for the National Register of Historic Places—most of them in Prescott. You have her to thank for the city’s impressive historic marker program, and she was the champion behind rehabilitating the Elks Opera House. The $2 million renovation of the 1905 theatre unveiled in 2010, the same year the Sharlot Hall Museum opened its grand “Buffalo Soldiers” exhibit at Fort Whipple.

She is like Sharlot, too; she also finds joy in hearing stories from Arizona’s pioneer families, and she has an impressive collection of early Prescott photos and postcards.

But Burgess would be the first to admit she did not do it all alone; the people of Prescott—42,000 strong—encouraged her vision and helped her every step of the way. Just last year alone, local groups collaborated to showcase Prescott and Yavapai County history from 1864-1912 (groups: Victorian Society, Prescott Regulators and Their Shady Ladies, Western Heritage Days and the Prescott Film Festival). Last October, the Arizona Women’s Heritage Trail launched its “Historic Women of Prescott” walking tour.

Summer brings heritage celebrations. The 1888 rodeo is still held during the Fourth of July, while the cowboy poets gathering is in August. Western art lovers can shop at the outdoor art sale in May to raise funds for the Phippen Museum, and at the Indian art markets hosted by the Smoki Museum in May and Sharlot Hall in July.

So where else but Prescott would Arizona kick off its celebration of statehood? Last September found Whiskey Row transformed into a massive Western village with re-enactments. So many of its 70,000 festivalgoers dressed up in territorial fashion that folks felt like they had stepped back in time—which was the point, of course.

Actually, any time of the year that you visit Prescott feels like a journey to the niceties and charms of Victorian life. The people who live here always seem to be willing to stick their necks out for each other and to share Prescott’s history, and their own stories.

Surveyor Robert Groom would be proud of how the town square he platted in 1864 still remains such a busy center of business and pleasure. Next time you visit, we recommend you raise a drink to him, and to all of Prescott’s citizens, at the 1877 Palace Saloon along Whiskey Row.

Photo Gallery

Grapevine: Grapevine Vintage Railroad

Prescott: Arizona’s Centennial Kickoff Celebration

– Sharlot Hall courtesy Library of Congress –

– Whiskey Row courtesy Nancy Burgess –