After the 13 Colonies rebelled against King George III, fife, drums and trumpets kept field commands attune to men in the heat of combat or on the march.

After the 13 Colonies rebelled against King George III, fife, drums and trumpets kept field commands attune to men in the heat of combat or on the march.

So it was that military music became part of the national heritage. Indeed, U.S. Army bands would serve in the War of 1812, the 1846-48 clash between Mexico and the U.S., and most notably during the Civil War from 1861-65.

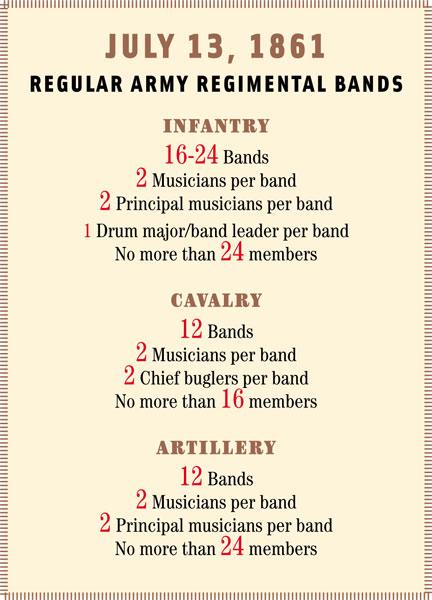

At the beginning of the duel between North and South, few military bands existed beyond those regiments posted to the frontier, the U.S. Military Academy and those groups associated with a handful of state and local militia outfits. Within a few months, however, the U.S. Congress authorized the creation of additional regimental bands for the Regular Army. This law was acted on by the War Department 150 years ago, on July 13, 1861.

As in the past, the field musicians served as a means of conveying signals in battle and performed certain ceremonial functions such as guard mount. The regimental bands remained a source of morale and entertainment. The latter group had other duties as well, especially if deployed in a combat zone where they might be pressed into service on stretcher duty or other non-musical functions.

A few bands remained in the West. For the most part, however, bandsmen and field musicians were found in the Union volunteer units. At one point, as many as 213 regimental bands served in the volunteer and state organizations.

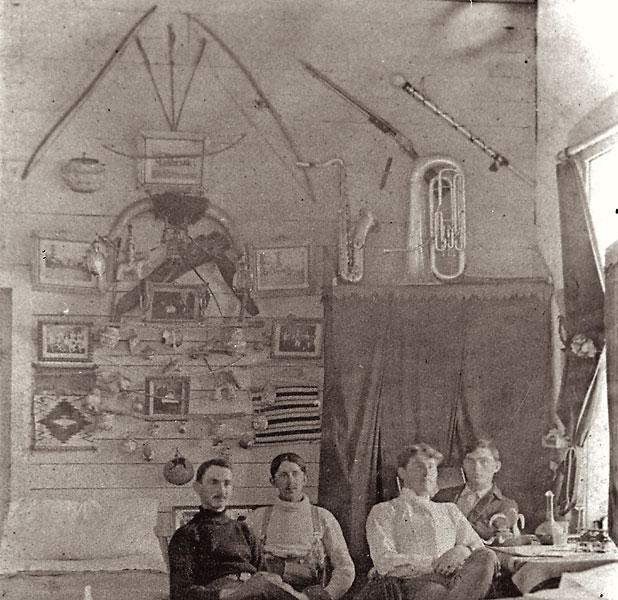

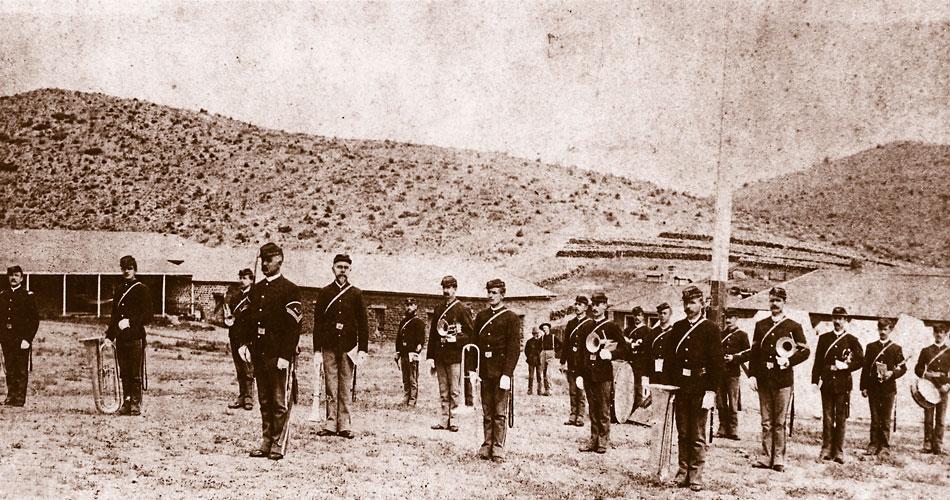

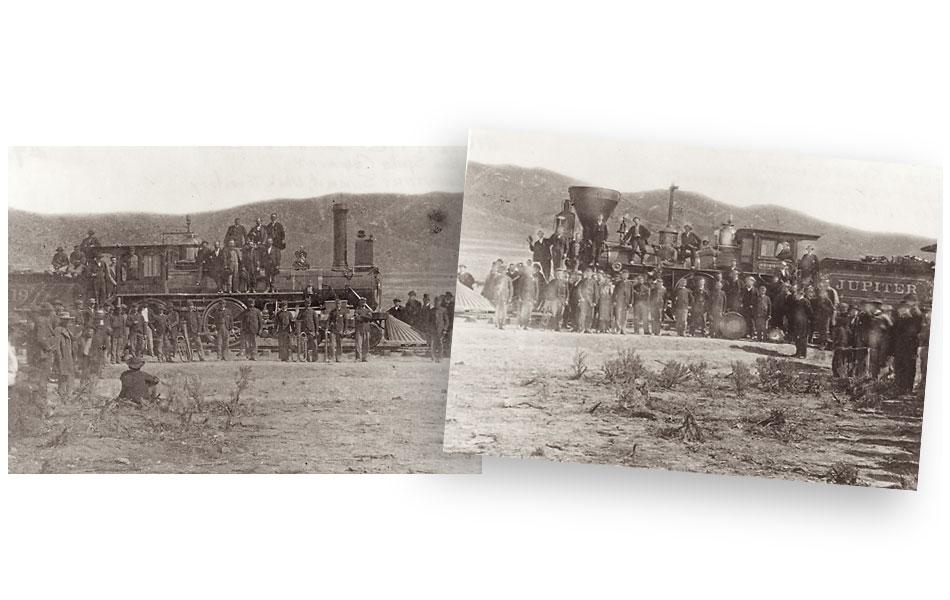

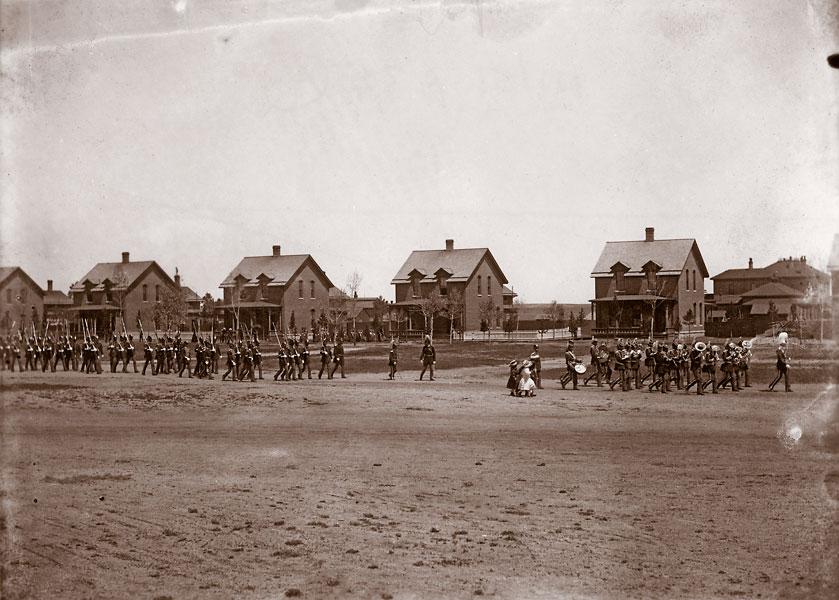

When the Civil War ended, however, the nation turned its eyes westward. The U.S. Army bands were sent there to provide music for parades and ceremonies. They brought culture and the trappings of civilization to the frontier. The bandsmen did much to foster relations between army garrisons and civilian communities, providing entertainment as concerts and playing for dances.

Army musicians rode with George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry at Washita, where they played in weather so cold, their lips froze to the mouthpieces of their instruments. Fortunately for these martial musicians, they did not accompany the regiment to the disastrous defeat at Little Big Horn in 1876, or they may well have been “Custer’s last band.”

The repertoires varied greatly depending on the resources and talents of those who headed the bands. Patriotic tunes, including “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” often found favor alongside marches and quicksteps, such as “10th U.S. Cavalry March” and “Annie May Quickstep.” Popular dance tunes played at “hops” ranged from “The Girl I Left Behind Me” and “Garry Owen,” the aire associated with the 7th Cavalry, to the “Palmyra Schottische” and “Soldaten Lieder Waltz.” Hymns and religious songs sometimes were played as well. Among them were “May Heaven’s Graces” and “Nearer My God to Thee.” Of course, a great many classical and orchestral transcriptions could be heard, with everything from a H.M.S. Pinafore potpourri to “The Light Cavalry Overture” being fair game.

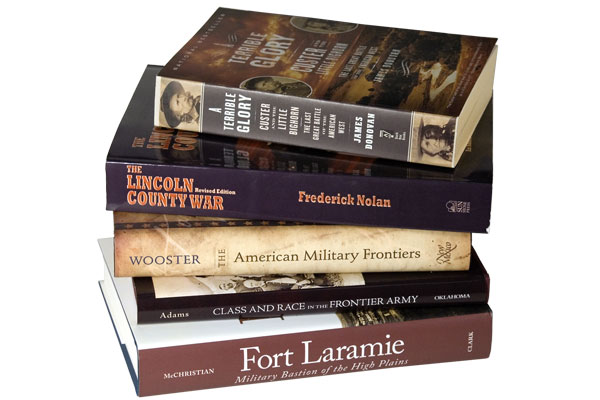

As with most of the requirements to maintain a regimental band, the instruments had to be bought with funds that were not from government sources. As such, the quality and types of instruments varied, but clarinets, cornets, trombones, tubas and various types of drums were staples in the regimental bands.

At the company, troop or battery level, fifes, drums and bugles were the norm. Although these instruments could be used for entertainment, they served a more practical function. Their main use was as a means for commanders to signal orders over the din of battle. In fact, John Martin was assigned to accompany Custer’s battalion on June 25, 1876, and he survived by a quirk of fate when he was sent with a message to Capt. Frederick Benteen to “Come on…Be quick” and bring the ammunition that never arrived.

When it came to entertainment on the frontier, army musicians were an important part of the rank and file. They not only provided communications in combat, but also livened up the often monotonous garrison life with their colorful tunes.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy U.S. Army Military History Institute –

– Courtesy Society of California Pioneers –

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy Utah State Historical Society –

– Courtesy National Archives –

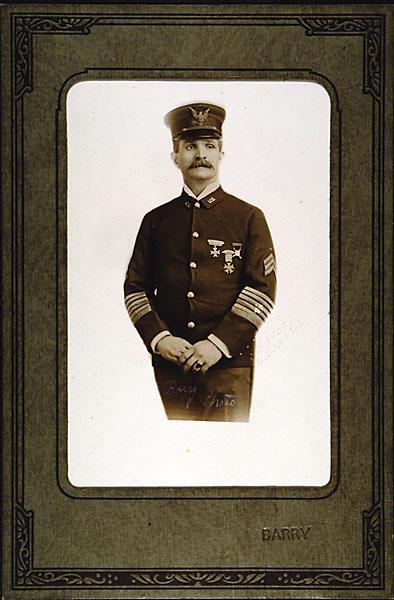

After coming to the U.S., Giovanni Martini changed his name to John Martin and served as George Custer’s orderly trumpeter on that fateful day at Little Big Horn.

–Courtesy Glen Swanson-

– Courtesy Kansas State Historical Society –

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution –

– Courtesy U.S. Army Military History Institute –

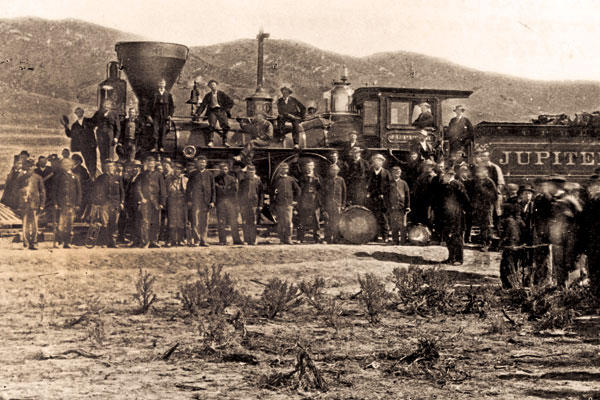

– Courtesy Golden Spike National Historic Site –

– Courtesy Wyoming State Archives –