The sign above the building front is optimistic, to say the least: Most Interesting Spot. Where Real Indians Trade.

The sign above the building front is optimistic, to say the least: Most Interesting Spot. Where Real Indians Trade.

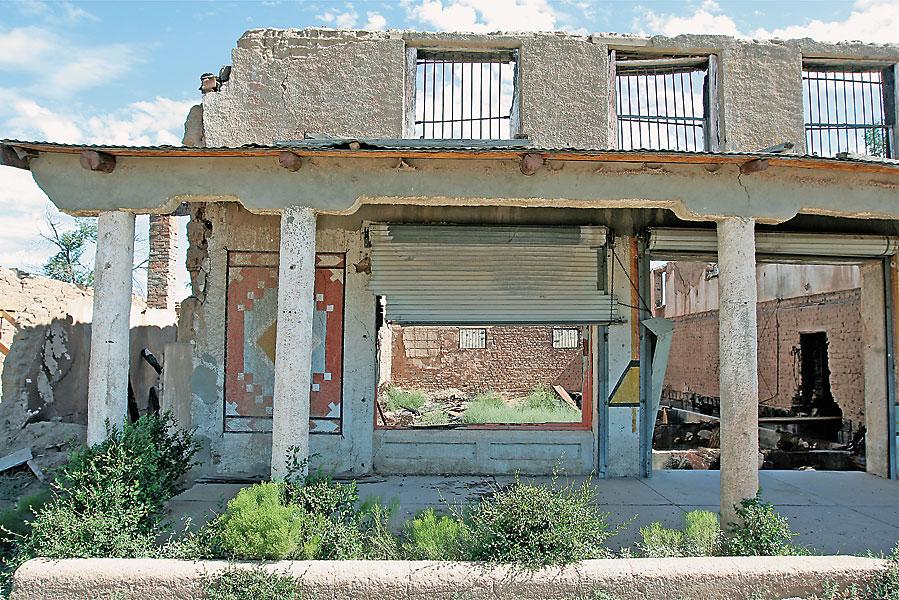

Nobody trades at the Kewa Pueblo Trading Post in northeast New Mexico nowadays. It’s a burned out hulk, with no roof or floor, just some walls

barely standing.

But commerce and business and art may thrive here once again, thanks to a federal grant and progressive thinking from the local Indian tribe.

The trading post dates to 1881, when it was built at a relatively new stop—called Domingo—along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway line. Most customers were locals, trading crops or art or money for basic goods.

Rebuilt in 1922, the post began catering to tourists, showcasing and selling American Indian jewelry and art. But Route 66 traffic slowed down after WWII—especially after Interstate 25 was built about six miles east of the pueblo.

The trading post closed in 1995. A fire almost totally destroyed the place in 2001.

But over the past 10 years, many folks at the Kewa Pueblo (formerly Santo Domingo) have had some big ideas for the historic trading post. Artisans could make and sell pottery, jewelry, weavings—not the tourist trap stuff, but the authentic, high quality goods. Perhaps native chefs could cook bread and traditional foods.

For those folks, 2010 was a big year.

First, in March, the New Mexico Rail Runner Express commuter train opened a station at the Kewa Pueblo. Each week, thousands of people traveling between Albuquerque and Santa Fe go within a few feet of the trading post—people who just might want to take a short stop or a day trip to see the place when it’s rebuilt.

In July, the federal Economic Development Administration allocated $1 million for the restoration of the trading post. Kewa Pueblo tribal officials say the money will cover everything from architectural design to developing a business plan to actually rebuilding the post.

The tribe has faced challenges with the project, says Kenneth Pin, the Kewa Pueblo planning director. It took some time to find an architect with experience working on historic structures (the trading post is on both the national and state historical registers). And the design was a problem. Although the tribe has plenty of photos of the outside of the 1920s post, it has no interior shots. The tribe’s luck changed a few months ago. “They had shot a movie in there back in the ’70s with Anthony Quinn,” Pin explains. “It’s called Flap. So we’ve looked at the DVD.”

Preliminary construction work has also come from unusual sources. Last April, a youth church group from Wellesley, Massachusetts, spent a few days making adobe blocks. Soon after, about 25 white-collar executives came to the pueblo for a community service project. They, too, got down in the dirt and learned how to make adobe bricks the old-fashioned way: by hand.

Between the two groups, the project ended up with about 800 blocks. The trading post needs somewhere near 4,000 blocks, but the tribe hopes other organizations will also volunteer their time to making adobe.

Kewa Pueblo officials hope future visitors to the trading post will learn about the local culture, keeping its history and traditions alive. But the project also carries a practical aspect. Increased tourism would bring new jobs (Pueblo officials estimate that the trading post alone could create 30 positions). Plus, new revenue streams—tourism—could bring much needed money to the area. Pin says more than a third of the residents are under the poverty line and unemployment is at 60 percent.

Construction crews are due to begin work late this summer. Pin believes the project could be finished as early as next spring.

If the dream is rebuilt, the Kewa Pueblo Trading Post will once again be a “Most Interesting Place,” one where real Indians and tourists trade.

Photo Gallery

The Kewa Pueblo Trading Post was virtually destroyed in an arson fire 10 years ago. Volunteer groups are helping to clear the rubble in preparation for opening the post for business once again.

– By Kate Nash / The New Mexican –