A young affluent St. Louis boy, born 150 years ago, who grew up in a wealthy suburb of Missouri, Charlie Russell made his dream finally come true in 1880 when he arrived in Helena. Joining him in Montana Territory were professional photographers who either had set up studios at military forts or towns,

or were itinerant. Many traveled the countryside snapping images of natural wonders, railroads, ranches and roundups.

The early photographs were taken with cumbersome, heavy wood cameras with poor quality lenses on glass plates, originally with wet emulsions that had to be developed on site. Contact prints were made by laying photographic paper on the glass negative and letting sunlight develop the image. Later, dry plates permitted development long after a picture was snapped.

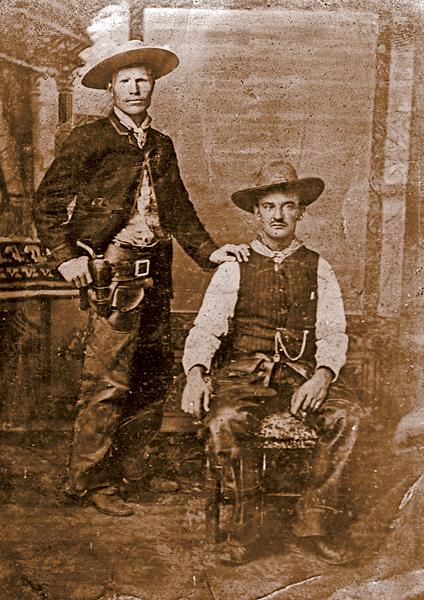

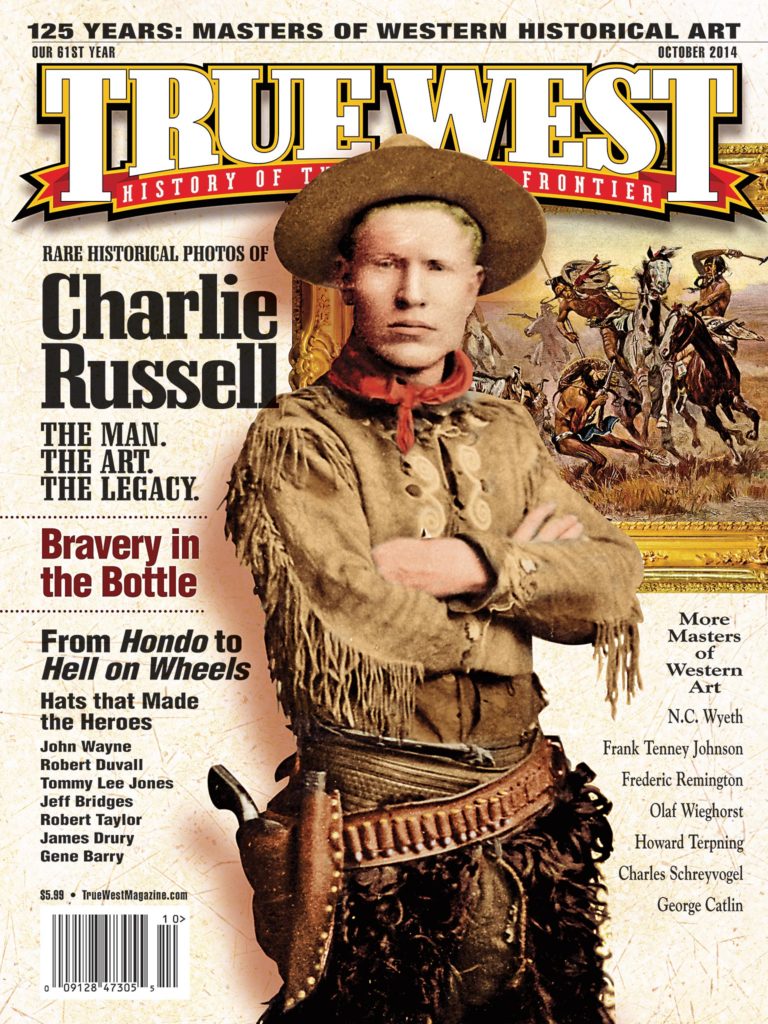

It was very fashionable for cowboys, when they had a break, to head to town and have their pictures taken. Photogenic and unforgettable in his cowboy costumes, Charlie enjoyed his visits to the photographer’s studio. He eagerly mailed pictures of himself back home to validate his status as a real cowboy to somewhat skeptical parents and friends. Charlie donned his best outfits for these occasions, but to avoid looking too much like a tenderfoot, he allowed his unruly bangs to roam wherever they wanted on his forehead.

The first amateur photographs of Charlie were taken around 1890 with a Kodak No. 2 mail-order camera that produced circular prints. He is seen smiling and holding a bucking horse model. George Eastman sold Kodak cameras to the public for the first time in the late 1880s. The camera came already loaded with film and was sent back to the factory in Rochester, New York, for processing. It was then reloaded and sent back along with the prints to the owner. The circular film was soon replaced by rectangular film used in a Kodak No. 3 in the early 1890s. Millions of Kodak cameras were sold to enthusiastic Americans. Even then, most of the photographs of Charlie were taken by professional photographers.

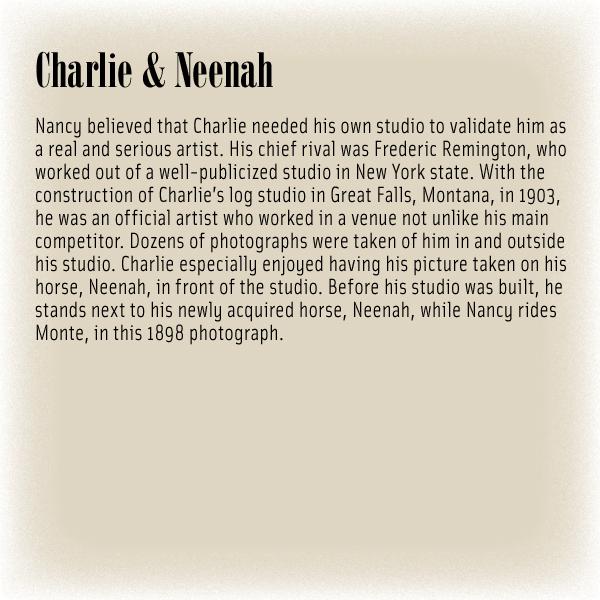

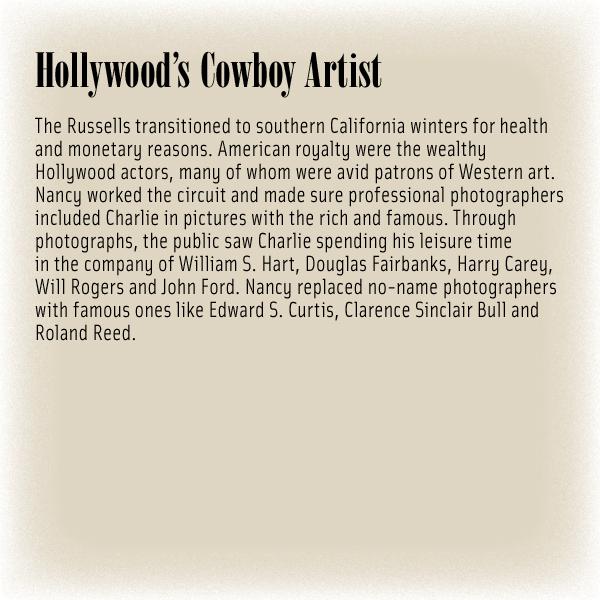

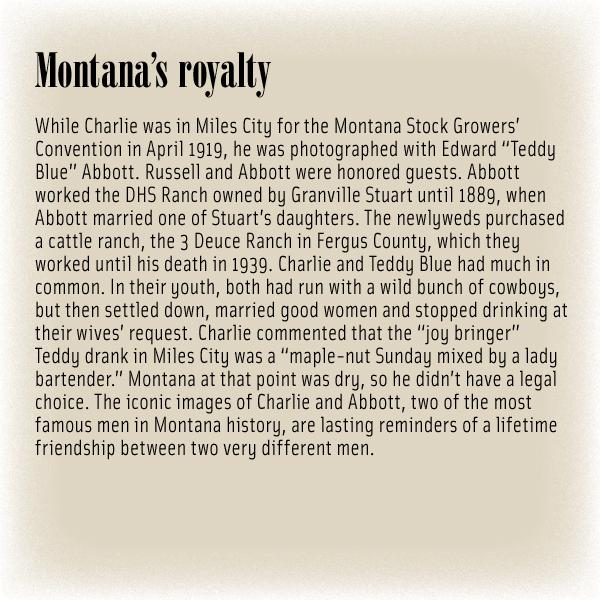

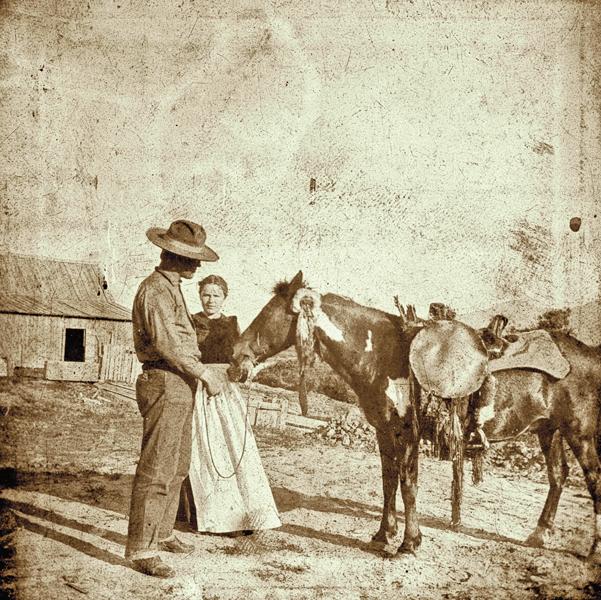

It was not until after he married Nancy in 1896 that more “Kodak moments” took place. Nancy grew up in Kentucky, a slave state that remained in the Union, but was actually represented on the Confederate flag during the Civil War. She was acutely aware of the power of photography. Nancy enthusiastically embraced photography from an early age. She owned a Kodak camera and enjoyed receiving, sending and trading pictures. All images of Charlie were taken with black-and-white film because color film was not widely available until around 1930. Colorized photographs were achieved by tinting black-and-white prints in the photographer’s studio. Charlie’s wagon boss maintained complete control of the distribution to the public of any images snapped of her famous husband.

Russell’s meteoric rise was due not only to the genius talent of the cowboy artist, but also to the business acumen of his manager wife. Nancy successfully used photographs of Charlie to promote his art nationally. A Russell painting was often associated with an image of the artist. In contrast, most contemporary artists were unknown to their patrons, but they didn’t have Nancy Russell.

Through photography, Charlie was famous even before he was great, monumental while still drawing breath, apotheosized while still very much alive. Photographs capture a moment that is gone forever and is impossible to reproduce. They keep a moment from running away. Photography needed a great subject, and in Charlie Russell it got one.

This edited excerpt is courtesy of Charles M. Russell: Photographing the Legend, by Larry Len Peterson and published by University of Oklahoma Press, in 2014, in honor of Russell’s 150th birthday.

Photo Gallery

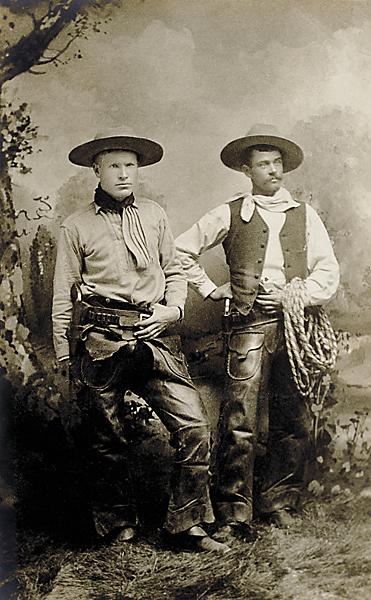

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.7648.1) –

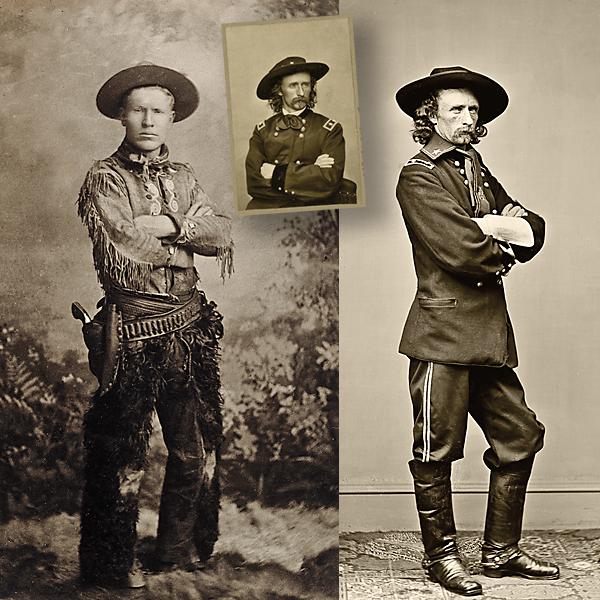

The Custer pose: Charlie and Ensign Sweet pose like Custer and Libby (previous slide). The original tintype was made in White Sulphur Springs, Montana, circa 1888.

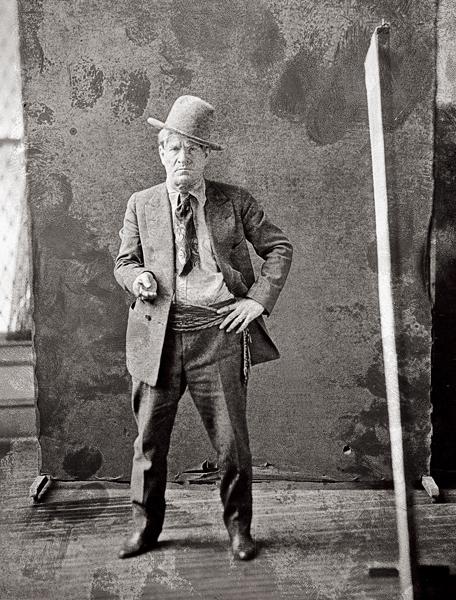

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.5674a) –

Charlie stands in his Hollywood cowboy stance at Federal Schools of Art in Minneapolis in 1922, four years before he meets his maker on October 24.

– Courtesy Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, Montana (Lot 9, box 1, f3.04) –

Norman Forsyth’s 1909 stereograph of Charlie mounted at the Pablo Buffalo Roundup is considered the most valuable one in the roundup set.

– Courtesy Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, Montana (ST 001.027) –

Charlie, painting inside the studio, 1910.

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.271.19) –

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.7647.7) –

Charlie made it to the film set of A Poor Relation, and he poses with Will Rogers on the Goldwyn Studios doorstep for one of the most famous and reproduced images of the cowboy artist. Their remarkable likeness would easily convince someone that they were brothers. The celebrated photograph was taken in 1921 by Clarence Sinclair Bull, who was born in Sun River, Montana, not far from Great Falls, the same year Charlie and Nancy were married.

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.262.81) –

After meeting Charlie in 1902, in Great Falls at the Grand Opera House, William S. Hart remained a close friend to Charlie (the actor sits next to Charlie in Los Angeles in 1920) and to Nancy long after Charlie had died. In the final months of Nancy’s life, Hart became a weekly visitor up to her death on May 23, 1940. She was buried next to Charlie in Highland Cemetery in Great Falls.

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.29.275.7) –

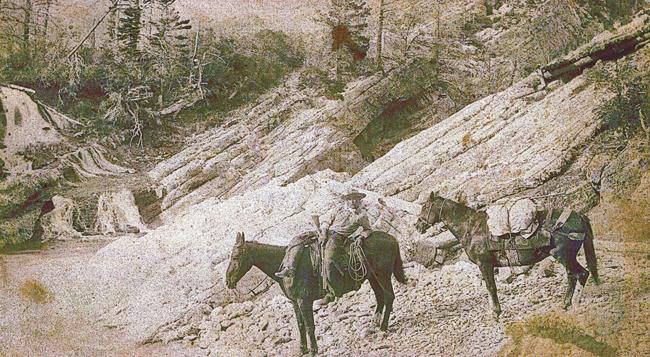

Taken in Montana’s Badlands before Charlie married Nancy and around the time of his first amateur photographs, circa 1890, this cabinet card shows Charlie mounted as he holds a rifle and the lines to his packhorse.

– Courtesy Jim and Fran combs Collection, Great Falls, Montana –

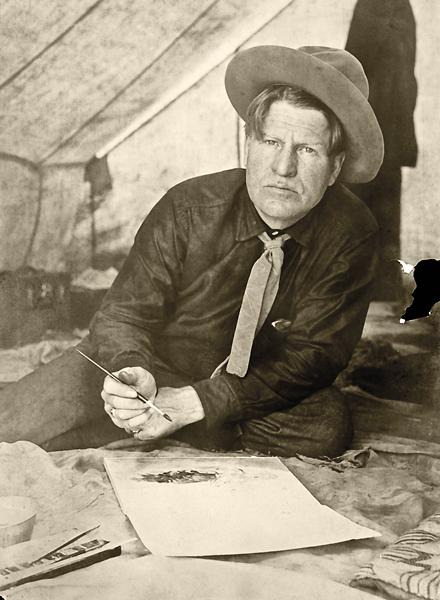

Charlie paints a watercolor in his tent at the Pablo Buffalo Roundup (one of four painted on site) in this M.O. Hammond photograph taken on May 25, 1909.

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.5672a) –

After Charlie arrived in Helena, Montana, in 1880, one of the first studio photographs taken of him portrays a confident cowboy posing with arms folded, just like Mathew Brady’s 1865 photographs of Custer.

– Russell photo Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.5667a); Custer photos Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.5647a) –

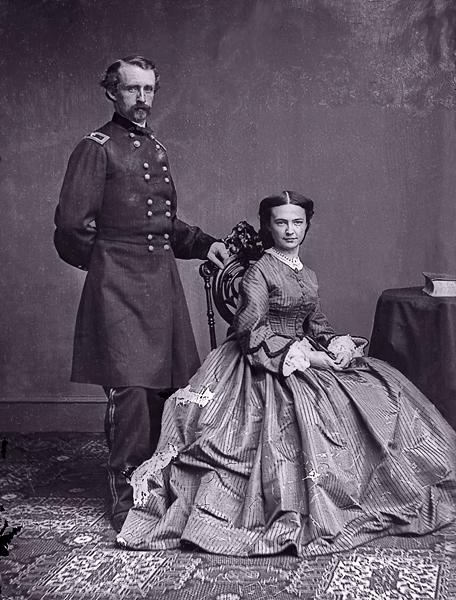

George Armstrong Custer and wife Libbie were photographed by Mathew Brady in 1864 in New York.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

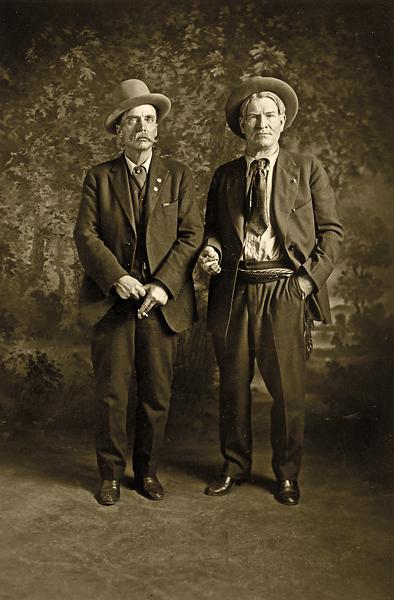

– Courtesy Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library Digital Collection, University of Montana, Missoula, Montana (010344) –

– Courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.5761a) –

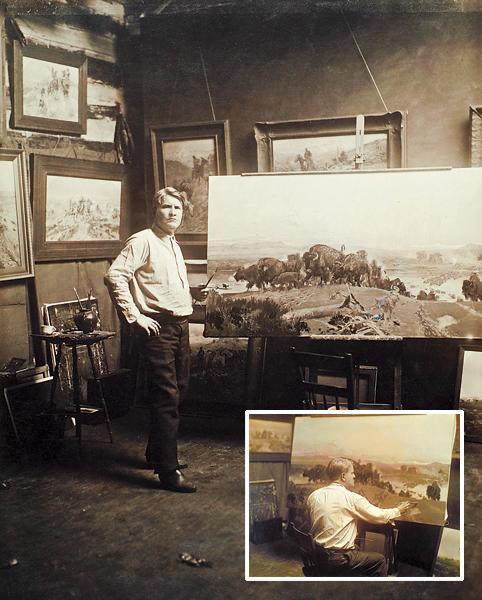

When the Land Belonged to God and Charlie Russell, in his log cabin studio, photographed by N.D. Stark in 1914.

– Left Courtesy Charles M. Russell research collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.5650a) / inset courtesy Charles M. Russell Research Collection, Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, Oklahoma (TU2009.39.5909a-b) –