The life of a frontier soldier in the American West involved more combat with boredom than forays against hostile tribesmen. Troopers adopted a variety of healthy ways to while away the endless hours of routine garrison duty, but for those with an inclination for alcohol abuse, whiskey offered an easy escape.

The life of a frontier soldier in the American West involved more combat with boredom than forays against hostile tribesmen. Troopers adopted a variety of healthy ways to while away the endless hours of routine garrison duty, but for those with an inclination for alcohol abuse, whiskey offered an easy escape.

In the case of Lt. Lovell Hall Jerome, accounts of heavy drinking are evident in many parts of his service record. Jerome’s 1875 report of the “battle” of Blackfoot Pass brings to light his possible skirmish with the bottle rather than braves.

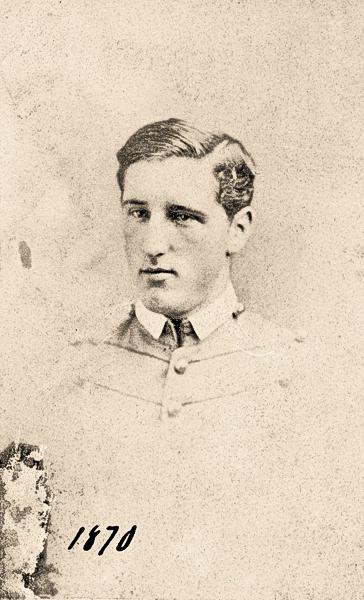

Born on August 6, 1849, into a wealthy New York family, Jerome grew up enjoying a life of ease. In addition to money, the Jeromes also had tremendous political influence. Some family members became especially prominent, such as his cousin Jennie, who married Lord Randolph Churchill and became mother to future British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. As a member of such a privileged family, Jerome gained a coveted appointment to the U.S. Military Academy in 1866. We can only guess if he began his apprenticeship as a heavy drinker at West Point, but after Jerome’s graduation in 1870, he certainly began his lifelong battle with booze.

Jerome received his commission as a second lieutenant and orders to join the 2nd U.S. Cavalry at Fort Ellis in Montana Territory along with classmates Charles B. Schofield and Edward J. McClernand. En route to their various assignments, many of the 1870 graduates passed through Omaha barracks in Nebraska. The three Montana-bound shavetails also stopped at the garrison where, in McClernand’s words, the “hospitality…for our preceding classmates continued to flow in our honor, and the post was indeed a merry place.”

The new officers consumed so much of the liquid cheer that they delayed their departure for days. The commanding officer had to order them to leave.

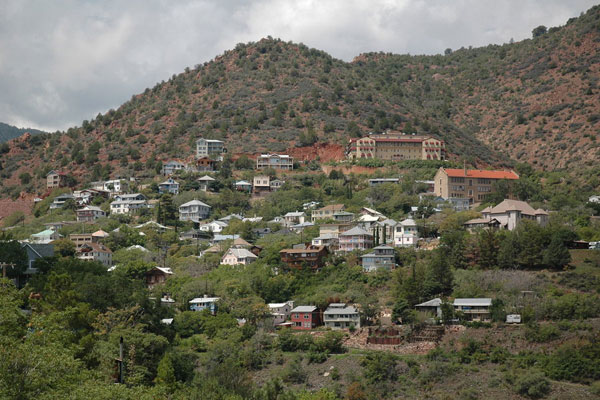

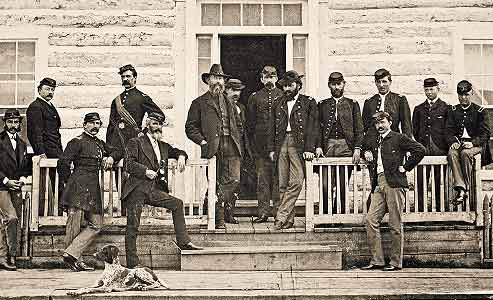

The military had established Fort Ellis in 1867 as a response to settlers’ imagined fears of an Indian invasion. Although the nearby hamlet of Bozeman never experienced an Indian attack, residents harped on the danger while also cheerfully selling whiskey to the idle soldiers every payday. Troopers didn’t even need to ride to town because the post sutler offered refreshment in a barroom inside the fort.

Peter Koch, the sutler’s clerk, described the situation as Jerome found it: “It is inspection day at the fort today, and the officers are here now on that duty, inspecting a few bottles of Champagne and some cigars, which is altogether one of their most important duties every day. They have never anything to do, except when officer of the day, drilling is something unknown, and consequently they have to drink whisky and play cards to kill time.”

Jerome’s defeats in his skirmishes with liquor are well documented. While on leave in 1872, he made New Year’s Eve visits to more than 100 New York City families and, according to a later newspaper interview, “does not remember if he took a drink at every house he visited, but thinks it very likely.”

Like most alcoholics in the 19th century, Jerome tried to fight alone what he perceived as a weakness, once reflecting that “as the habits of dissipation…grew upon me, my associates dropped off.”

Trying to hide the effects of his drinking from his superiors, and the cost of it from his father, became increasingly difficult for Jerome. Bozeman resident William W. Alderson recalled a bartender once confronted Jerome with a liquor bill that exceeded $500 and threatened to send the bill to the lieutenant’s father. After Jerome begged the man to send it to his mother instead, the invoice was quietly paid.

Desperate for money on another occasion, Jerome turned to gambling with humiliating results. He was slapped and kicked by an outraged Bozeman faro dealer when he discovered the young wastrel lacked the money to back any of his bets.

During the summer of 1875, Fort Ellis’s commander decided to establish a camp at Blackfoot Pass in the Bridger Mountains, some 30 miles northeast of the post. The purpose of the camp was to monitor Indian movements, even though troops were likely to only see hunting parties heading to the buffalo plains.

When Jerome led a detachment to the camp on June 14, the men began their march from Fort Ellis at 8:00 a.m. Yet their lieutenant quickly left the column to, in his own words, “attend to some important private business.”

What that business could have been is unknown, but the prospect of two boring weeks at a remote mountain pass could have motivated any officer so inclined to seek out supplies not provided by a quartermaster. Regardless of the nature of his “private business,” Jerome failed to rejoin his command at Blackfoot Pass until 10:30 the next night.

For the next several days, Jerome sent troopers over the pass and down into the Shields and Yellowstone River Valleys to monitor Indian movements. The men returned each time, seeing nothing more than a herd of ponies. Although we have no way of confirming that the lieutenant spent his time tippling while these patrols did their work, at midnight on June 23, he took an action that calls into question any officer’s sober judgment.

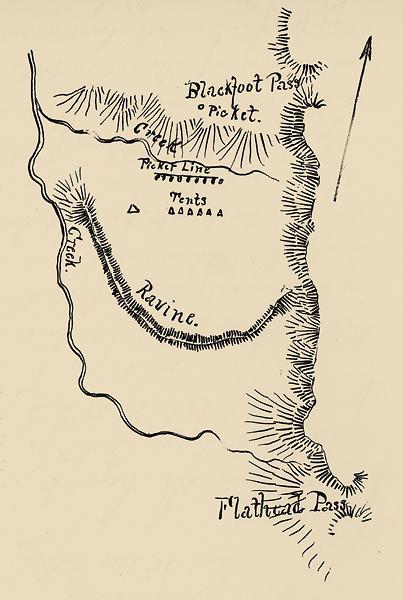

“The camp was aroused by the tramp of horses passing by it through the ravine to the east of it,” Jerome wrote. He ordered his slumbering men to awake and form a skirmish line facing what he “supposed to be a party of Indians forming and coming steadily, noiselessly and slowly towards camp from the south side.”

Without waiting to see the approaching horses, Jerome ordered his men to fire four volleys into the darkness. When they did, he was satisfied that the “advancing party fled through the ravine by which they had come in.”

Unfortunately, about an hour later, the sound of horses returned. But this time, the shaky lieutenant could see in the pale moonlight the horses were simply some of the ranch ponies his men had spotted earlier that week; two of them lay dead on the ground.

Since the enlisted men had only carried out his orders and could provide witness to their ill-advised nocturnal volleys, Jerome had little choice but to be honest in the report he wrote on June 28 after returning to Fort Ellis. He even drew a map of the “battlefield,” along with a description of the brand markings on the two casualties. Record books confirm the dead ponies belonged to the H.H. Clark Ranch, located more than 60 miles to the northwest of Jerome’s camp. How the horses had wandered that far remains a mystery, as does Clark’s failure to press a claim against the government for the wanton destruction of his property by a nervous junior army officer.

Fortunately for Jerome, rumors that month of Sioux advancing toward Gallatin Valley helped panicky Bozeman citizens overlook his incident. A June 18 letter by newspaper editor John Bogert to the Fort Ellis commander discussed Indian signs discovered near Crow Agency, located roughly 100 miles southeast of the Blackfoot Pass camp. He ridiculously suggested the Crow might be forming an alliance with their traditional enemies, the Sioux. Bogert told his readers Jerome’s “affair was unfortunate, but we cannot blame Lieut. Jerome for his course—it being the only one any vigilant officer should have adopted.”

The Army apparently agreed because records do not cite Jerome ever faced censure for his part in the debacle.

In the years following, Jerome continued to battle for sobriety. In February 1877, he narrowly avoided a court martial by signing a pledge to never drink again. Even if he kept his promise, Jerome displayed another lapse in judgment later that year during the Nez Perce War.

When Col. Nelson Miles cornered Chief Joseph’s band at the Bear Paw Mountains on September 30, the Indians dug entrenchments and prepared for a siege. During an uneasy truce the following day, Miles had a brief parlay with Joseph and decided to detain the chief.

Jerome, either by order or on his own authority, scouted the enemy positions, successfully returned to his own lines and then “let his curiosity lead him back again, even though the interpreter warned against it.”

Because Jerome clumsily stumbled into the hands of the Indians, Miles had no choice but to release Joseph in exchange. Although Jerome tried to later portray his role in the prisoner swap as a courageous act of self-sacrifice, his misadventure undoubtedly outraged Miles by complicating the colonel’s attempt to bring the siege to a rapid conclusion.

Whiskey resumed its role as Jerome’s main enemy later in 1877, when he took six month’s leave starting in November. In New York City, he checked into the Sturtevant House hotel for a riotous debauch that ended only when he developed a case of the delirium tremens.

In May 1878, Jerome returned to active service at Fort Snelling before moving on to Fort Custer and Fort Ellis. At each place, he was found drunk on duty. The Army finally had enough of the lieutenant when he borrowed $86 from a private and failed to repay it. Lieutenant Gustavus C. Doane passed the hat among his fellow 2nd Cavalry officers to repay the hapless enlisted man and then filed formal charges against Jerome.

Jerome’s court martial conviction occurred in January 1879, but he was allowed to resign before the sentence was approved. He returned to New York to face his family and then, incredibly, rejoined the Army in 1880. Assigned to the 8th Cavalry in Texas, Jerome wrote he was determined to “win my commission back or never return,” but his battle against alcohol continued to go badly. After being caught several times for drunkenness on duty, he faced court martial at Fort Duncan in January 1882. He was again allowed to resign.

Once he returned to civilian life, Jerome straightened up a bit. Family connections got him government positions in Texas and Arizona. In 1886, when companies of the 2nd Cavalry camped temporarily at Fort Bowie, Jerome visited his former comrades. Doane, who had filed charges against him, wrote to his wife that Jerome “…is in the custom house detective service, has a good place, and is doing well…. He was very friendly and appeared to be glad to see all of us.”

By 1888, Jerome had returned to New York to live off investments. He called himself “Colonel” and attempted unsuccessfully to get a commission as a brigadier general of volunteers during the Spanish-American War. When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, Jerome brashly petitioned for a Medal of Honor for his 1877 field service. Perhaps hoping that time had obscured his true record, the former hostage received a disappointing reply from Roosevelt who bluntly stated Jerome had done “nothing to show that you distinguished yourself.”

Toward the end of his life, Jerome continued to emphasize his self-styled heroism as a volunteer hostage during the Nez Perce War as well as fought his unsuccessful battle against the bottle. In 1933, a reporter who interviewed Jerome said that he daily “drank as much beer as he wanted, no more, and no less.”

By then The New York Times had begun putting Jerome’s bogus title of colonel in quotation marks, even as the newspaper continued to praise him for his hostage experience and lauded his efforts to organize a West Point reunion. Charitably, the newspaper referred to the termination of Jerome’s service as his “retirement” and never mentioned his less savory career skirmishes. In that sense, when Jerome died on April 17, 1935, he could claim partial victory in his lifelong struggle with alcohol, perhaps hoping the accounts of his confused action in the “battle” of Blackfoot Pass would die along with him.

Professor Kim Allen Scott is the university archivist at Montana State University Library in Bozeman. His in-depth biography of Gustavus Doane, Yellowstone Denied,was published by University of Oklahoma Press in 2007.

Photo Gallery

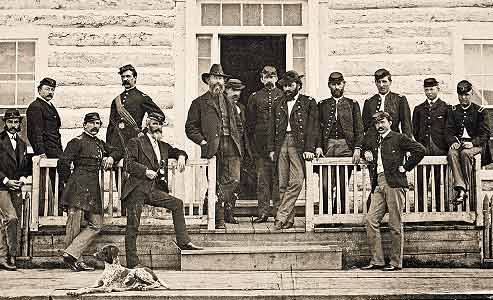

– Courtesy National Archives, Washington, D.C. –

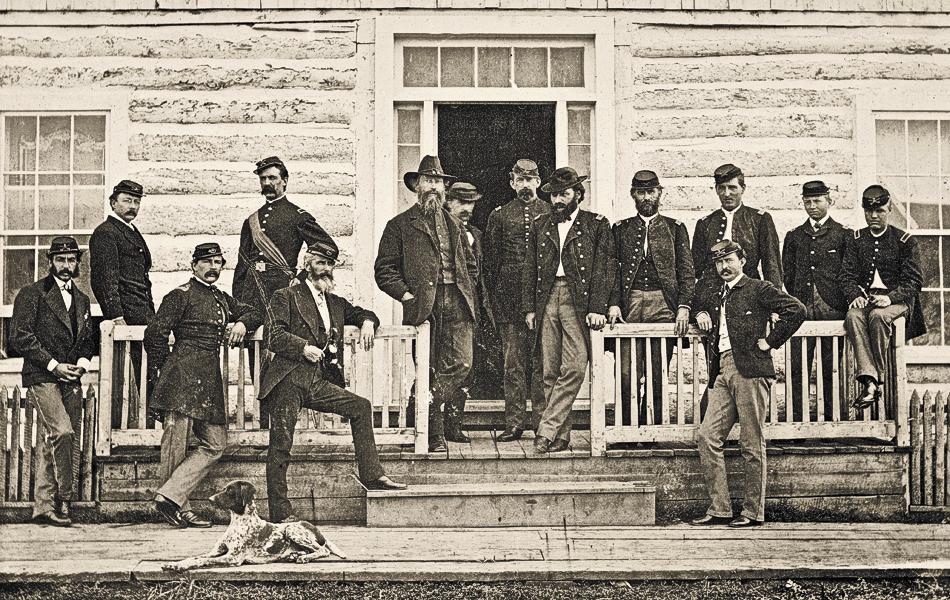

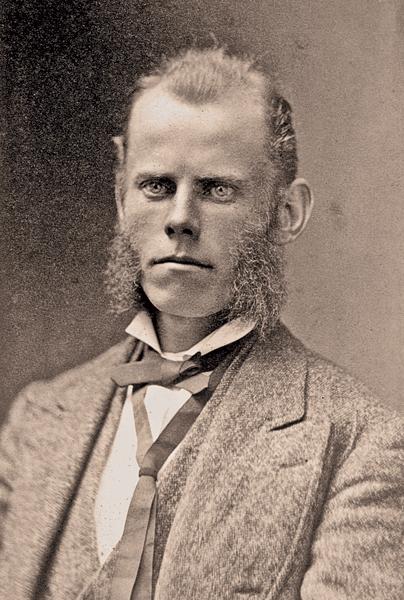

– Courtesy Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman, Montana –

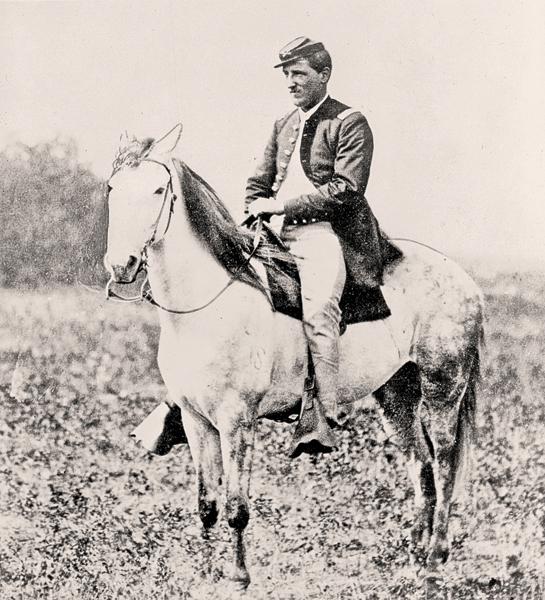

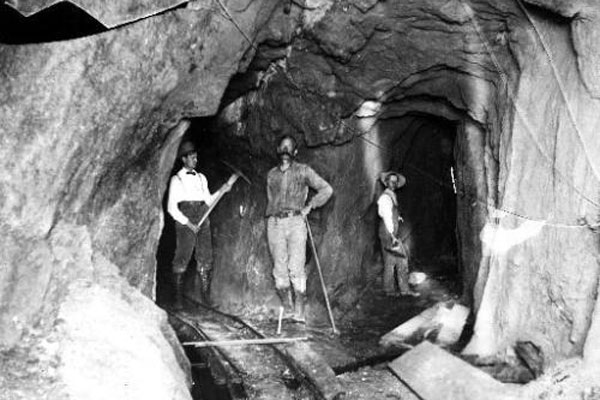

– Courtesy Montana Historical Society, Mrs. John Sloane, New York City –

– Courtesy Montana Historical Society, Mrs. John Sloane, New York City –

– Courtesy Montana State University Library –