The last great year for Western movies was 1969, which saw the release of three classics: The Wild Bunch, True Grit and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (all three films feature actor Strother Martin in memorable roles). Getting three terrific Westerns in the same year seemed exceptional at the time, and it now seems beyond imagination.

The last great year for Western movies was 1969, which saw the release of three classics: The Wild Bunch, True Grit and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (all three films feature actor Strother Martin in memorable roles). Getting three terrific Westerns in the same year seemed exceptional at the time, and it now seems beyond imagination.

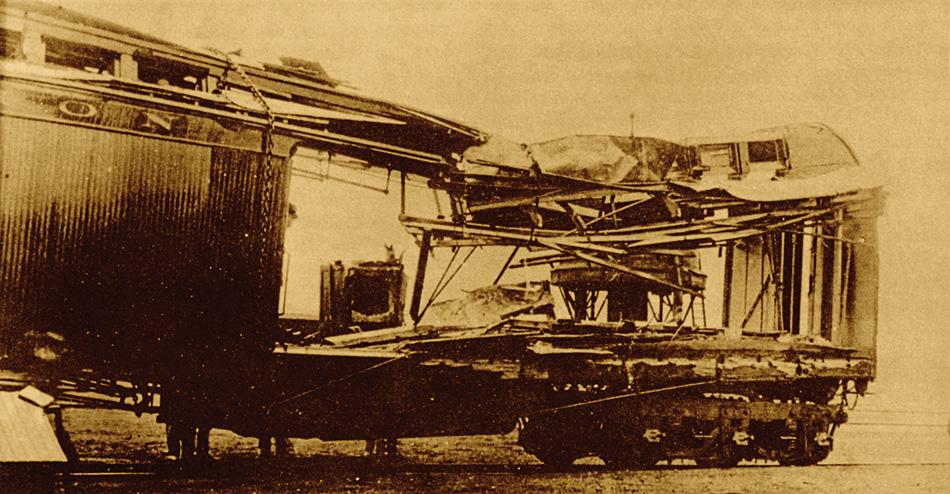

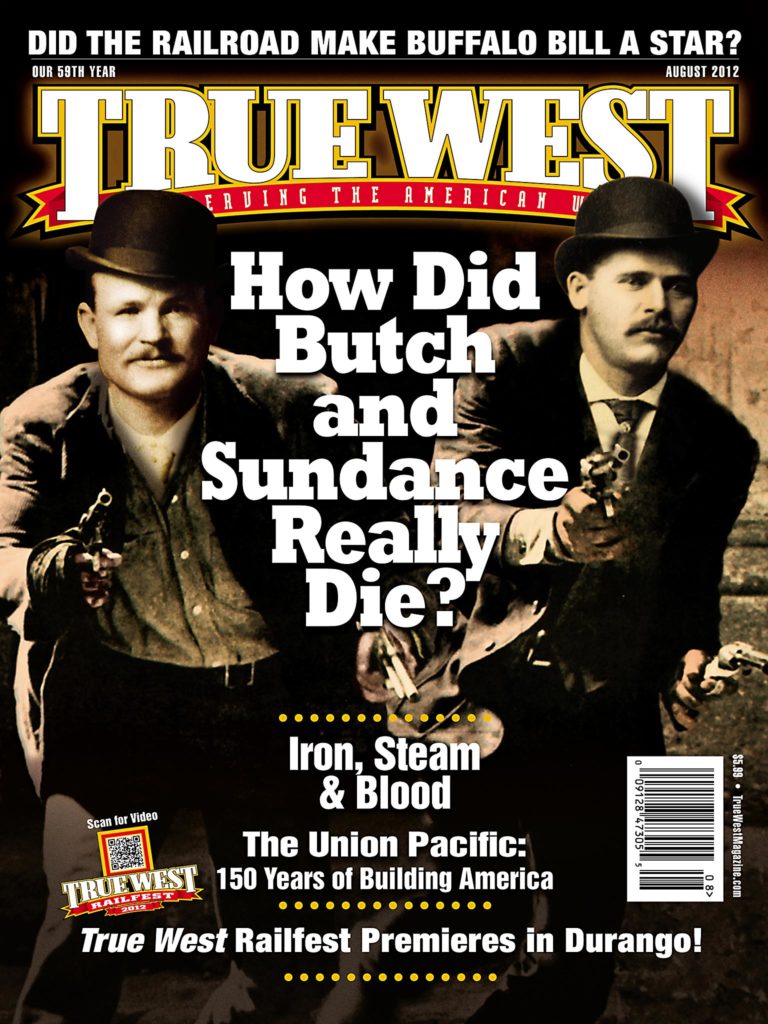

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid tells the story of two real-life outlaws who were members of the Hole in the Wall Gang, otherwise known as the Wild Bunch, in the late 1890s. No doubt these men had grit—true grit.

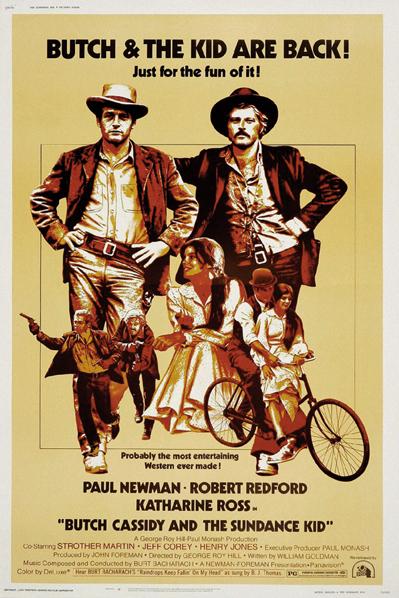

The film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was an instant classic nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Picture, then went on to win four: Best Original Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Original Song and Best Original Score.

Nevertheless, a lot of movies have been nominated for, and won, Oscars that were completely forgotten within a couple of years. That’s not the case with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; it’s a truly beloved movie that never stops being shown, and in 2003, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically and aesthetically significant.”

So what is it about this film that makes it so significant? Historically, it’s not all that accurate; culturally,

it’s about outlaws who terrorized the West (and South America) for nearly 20 years, robbing banks and trains, and killing any number of innocent people; aesthetically, it’s a beautiful piece of filmmaking, but so are a lot of films that are quickly forgotten. Honestly, I don’t think any of those reasons answers the question of why this film remains so popular.

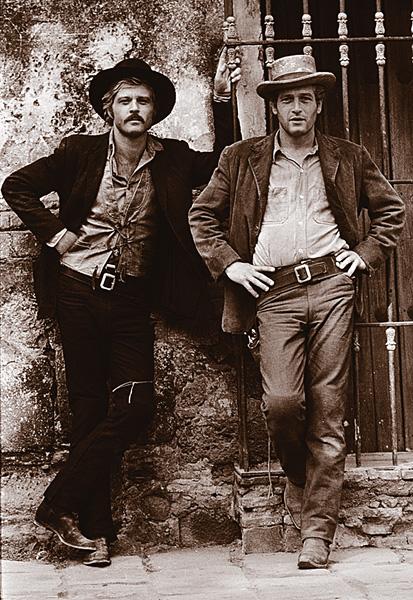

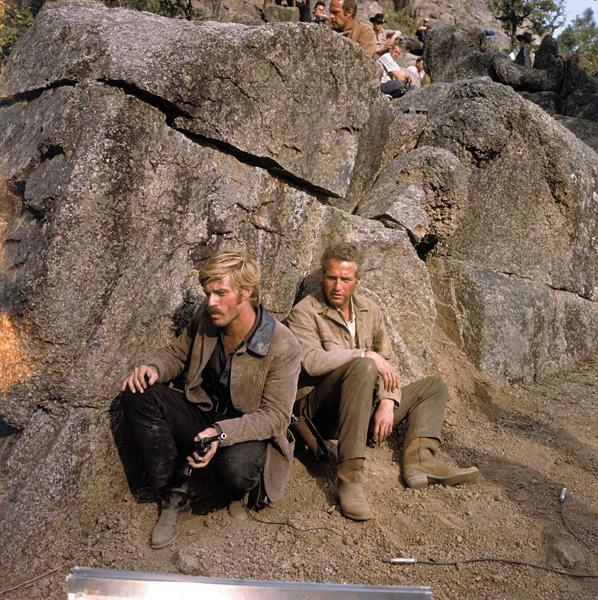

First, it’s funny, and consistently so from the beginning to the end. The film has an amused, almost joyous tone, incongruously set against the milieu of robbing banks and trains. Second, such amazingly strong chemistry exists between Paul Newman’s Butch and Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid that it’s a pure delight to be in their company. Although the characters as written completely complement each other—Sundance is a great shot, Butch isn’t; Sundance has killed a lot of men, Butch hasn’t; Butch is an idea man, Sundance isn’t; Butch is upbeat, Sundance is rather serious—in both cases each one appears to reserve an unshakable respect for the other’s capabilities.

The part of the Sundance Kid, a man of few words, was originally offered to Steve McQueen, an actor I think would have been a good choice. But Paul Newman and McQueen couldn’t settle on the billing. (This issue would reemerge six years later when the two actors co-starred in Towering Inferno. They solved the problem by putting McQueen’s name first and Newman’s name higher.)

The part was next offered to Jack Lemmon, of all people, and thankfully he turned it down because he didn’t like riding horses.

So the part of the Sundance Kid was finally offered to the up-and-coming young actor Robert Redford. But Redford was anything but an overnight sensation. For seven years his career had been a series of false starts, with him starring or co-starring in one stinker after another, like Situation Hopeless–But Not Serious, Inside Daisy Clover, The Chase and the particularly dreadful This Property is Condemned. The fact that he didn’t become a star after the hit 1967 film Barefoot in the Park (a part he’d already played on Broadway) was almost inexplicable. That film did, however, ultimately lead to him getting the part of the Sundance Kid, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Newman, co-executive producer of the film, made a number of inspired choices, first and foremost being the hiring of director George Roy Hill. Hill was an interesting man: a Navy fighter pilot in both WWII and Korea, he retired from the military with rank of major, went into directing TV and theatre, then made his movie directorial debut at the age of 40. Although none of the films he’d made prior to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid even hint at how good he would soon become, he had received good reviews and made money with silly nonsense like Thoroughly Modern Millie. With Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, however, Hill really exerts a strong cinematic influence throughout the film, using interesting angles and compositions, slow motion, long telephoto lenses and one lengthy montage done entirely with sepia-toned still photos.

The incredibly talented cinematographer Conrad Hall had already worked with Paul Newman on Harper and Cool Hand Luke. Newman knew a talented person when he saw one, and Hall was the perfect man for the job; his photography is absolutely gorgeous and deservedly won him the Oscar. Mr. Hall would win the Oscar again 30 years later for American Beauty.

But as great as Newman, Redford, Hill and Hall all were, the key aspect of the whole film was William Goldman’s brilliant original screenplay, for which he won his first Oscar (the second was for All the President’s Men). Goldman, the guru and old man of the sea of screenwriters, and the author of the standard text about what it’s like to be a screenwriter in Hollywood, Adventures in the Screen Trade, became interested in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in the late 1950s. In a burst of inspiration in 1966, he knocked out the script in four weeks, then was paid the astounding sum of $400,000 for the script (that’d be equal to $2.77 million today).

Goldman’s script creates a relationship between the inspired, indefatigable, idea-ridden Butch, and the tight-lipped, stoic, crack-shot Sundance—while they’re being chased by a posse all over hell and creation—that’s extremely funny, highly enjoyable and ultimately moving. As top-notch as the entire production was around it, Goldman’s script was the core of the whole project. Everyone knew it, then did him the great service of not screwing it up.

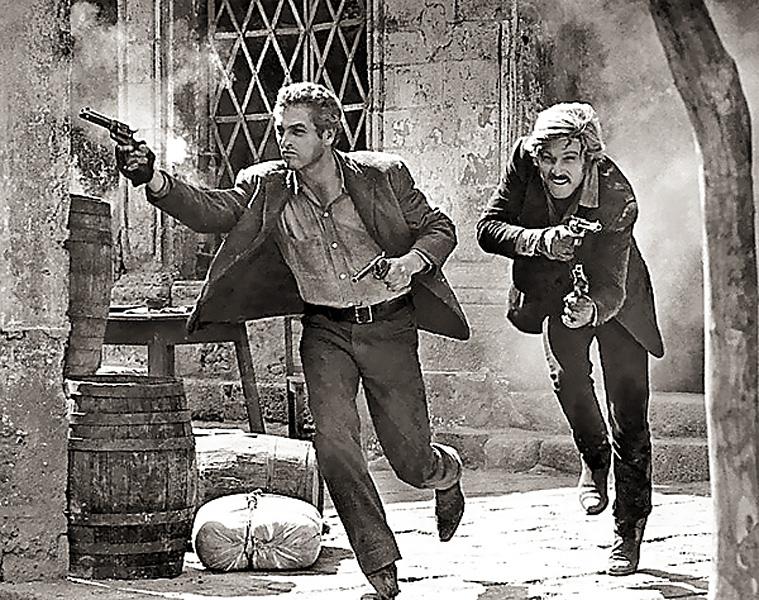

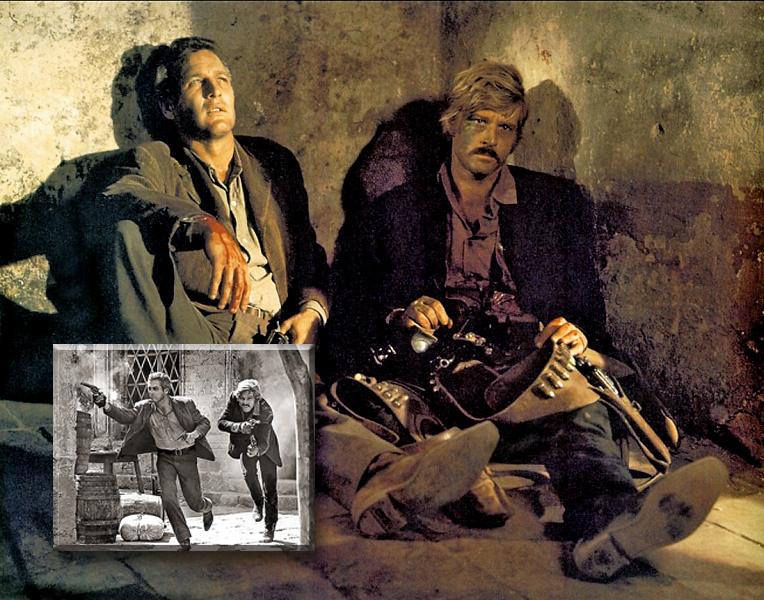

In the last shot, as Butch and Sundance are both wounded several times each and, unbeknownst to them, are being surrounded by hundreds of Bolivian soldiers, Hill, Hall and the famous special effects man Albert Whitlock pull off an astounding, completely unnoticeable effect. Butch and Sundance step forward out of a doorway, each with two guns blazing, and this scene freeze frames into the shot that would become the movie poster. But then our view of the two men begins to pull back and back and back until we’re watching them from across the whole town. Well, if the film were rolling and it wasn’t a freeze frame (or they had gone and bothered to invent digital effects), then they could have just used a giant zoom lens and zoomed back as far as they wanted. However, since we’re starting on a freeze frame of the two men filling the frame, what are we pulling back to? How can there be so much image all around them to reveal? The film is only 35mm wide after all.

What Whitlock did was photograph the two men exiting the doorway from across the town with a large-format 8×10 still camera. The photograph was put on an animation stand, and the animation camera was zoomed all the way in to the shot of the two men holding their pistols. But since it’s such a high-quality photo, the image is reasonably sharp, and the pull-back is finished on the photo. It’s an incredibly clever, subtle effect and a powerful finale.

Sadly, however, the scene is flatly untrue. Instead of hundreds of Bolivian soldiers there were in fact three, plus their commander, who enlisted the aid of several local townspeople in surrounding the boarding house where the bandits were hiding. The two outlaws, who were never officially identified as Butch and Sundance, proceeded to have a protracted shoot-out that lasted well into the night. Finally, after the shooting had stopped, a scream was heard from within the boarding house, followed by a single gunshot. Moments later there was another gunshot. When the dead bodies of the two men were inspected, both with many bullet wounds and each with a bullet wound to the head, the assumption was that one of the men shot the other man, possibly to put him out of his misery, then subsequently committed suicide by shooting himself in the head. The unidentified dead bodies were buried in unmarked graves in the town of San Vicente.

As they say in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Goldman wrote the legend, not the facts, and it plays beautifully. This is a Hollywood Western after all, so I don’t think anyone really expects all (or any) of the facts to be true anyway.

The film’s ending, though, is spectacular, violent and highly amusing, not an easy trio of emotions to juggle. Not only do Butch and Sundance get shot hundreds of times—at least, that’s what it sounds like—but they’re funny right up to the last second. This is a magical balancing act that only the very best in the business could possibly get away with, and they do, brilliantly. Even though Butch and Sundance are anti-hero outlaws, the film manages to build up a tremendous sense of empathy for them. When the picture freezes and we hear volleys of rifle fire, we sort of feel like we’ve just lost two of our best friends.

My only real gripes with the movie are Burt Bacharach’s silly, dated Oscar-winning score and the overly-cute, utterly extraneous Oscar-winning song, “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head.” However, since the music is so typical of the time, 1969 (Woody Allen’s movie that year, Take the Money and Run, has a similar score), I’m nostalgically transported back to a time when

they actually made three great Westerns in one year.

Josh Becker is the internationally-known director of Xena: Warrior Princess and Hercules, has directed seven feature films and has been a proud member of the Directors Guild of America for 19 years. His latest book is Going Hollywood by Point Blank.

“</p>”</p>”</p>”</p>”</p>”

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation unless otherwise noted –