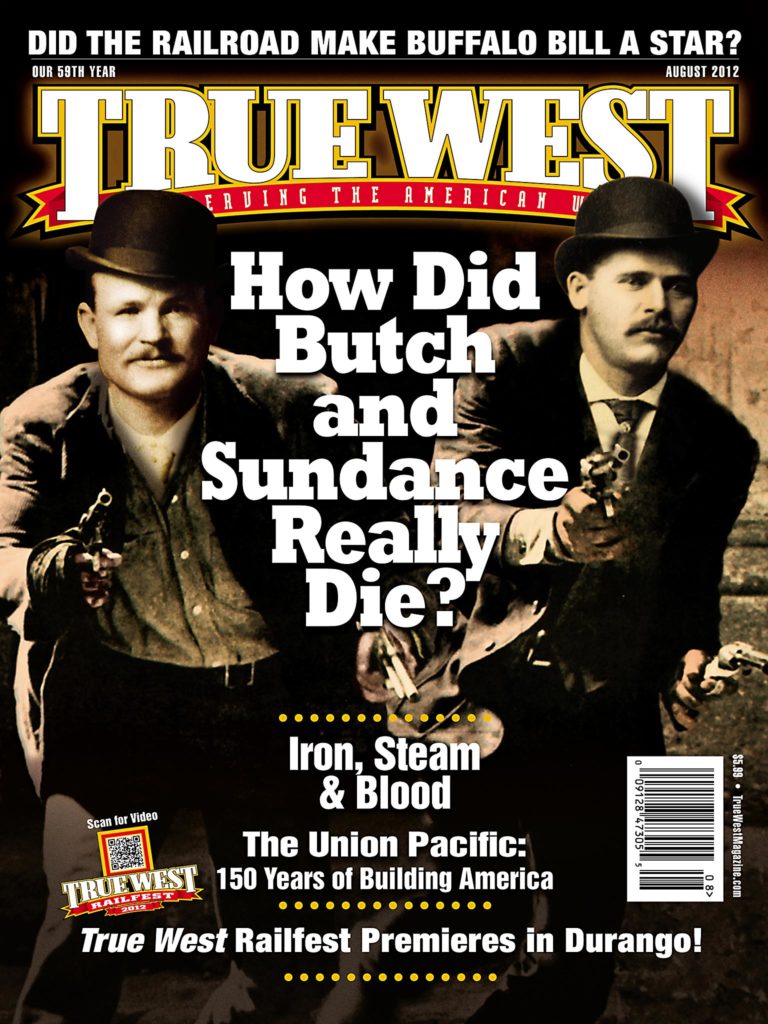

In the year 1869, dime novel king Ned Buntline aspired to write one of his corkers about Frank North, the famed scout and Indian fighter who was known as the “white chief of the Pawnee.”

In the year 1869, dime novel king Ned Buntline aspired to write one of his corkers about Frank North, the famed scout and Indian fighter who was known as the “white chief of the Pawnee.”

The two met to talk it over. North turned down the exposure: “If you want a man to fit that bill, he’s over there sleeping under the wagon.”

The snoozer was Buffalo Bill Cody.

If anybody was the anti-Cody, it was North. He usually dressed in cowboy duds or business suits or military uniform, not buckskin. He was a successful merchant in addition to his frontier exploits. And, as the story (which may or may not be true) suggests, he wasn’t a publicity hound.

But if not for a show North and his Pawnee friends had organized on behalf of the Union Pacific Railroad in 1866, Cody might have been little more than a second-rate actor, telling whoppers on stages across America.

The Union Pacific’s Monumental 100th Meridian Excursion

North and his family moved from the East to Nebraska when he was 16. A quick study, he learned the Pawnee language and, in 1860, became a clerk and interpreter at the tribal agency near his home in Columbus. The Indians, who had always been friendly toward the U.S., trusted him—so much so that at the Army’s request, he formed a company of Pawnee scouts in 1864. Scouting was only part of the duty; North’s group also fought other Indians, mostly Cheyenne and Sioux, traditional enemies of the Pawnee. (The scouts were so successful that the military would call on their services through 1877.)

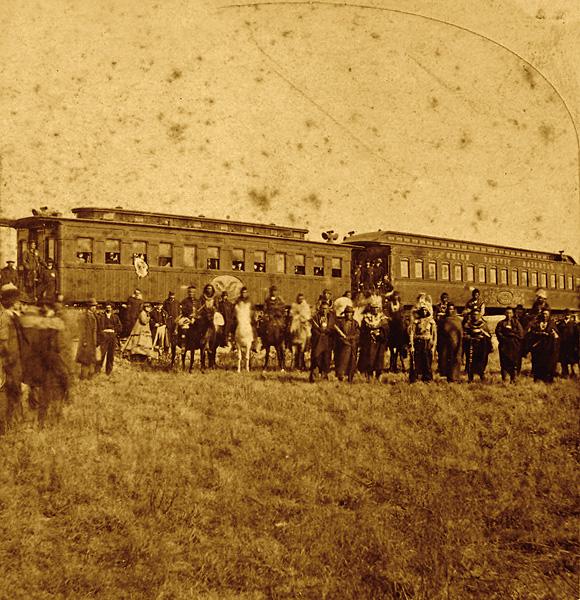

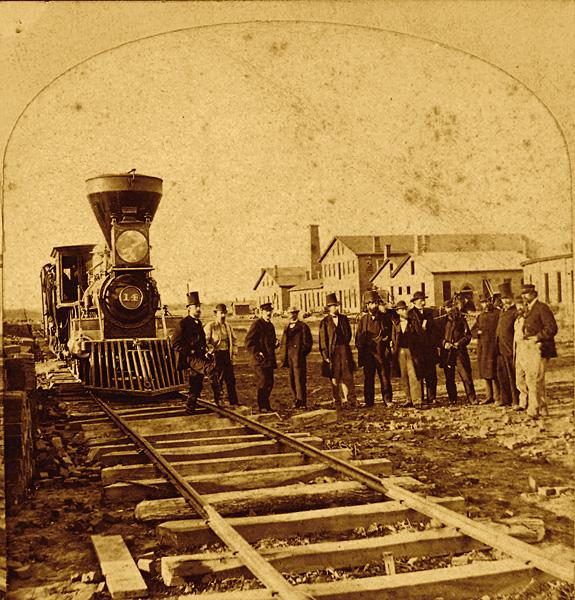

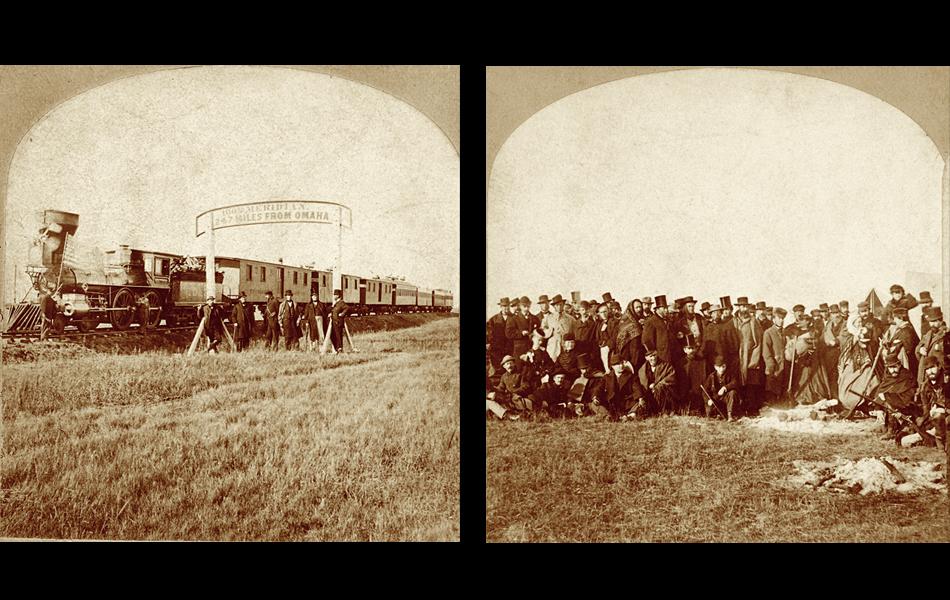

In 1866, North and his Pawnee were given a special job. The Union Pacific was going to reach the 100th Meridian—247 miles west of Omaha, Nebraska—on October 5, ahead of schedule by a year. As stipulated in the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, passing the 100th Meridian gave the Union Pacific the irrevocable right to continue westward as part of the Transcontinental Railroad project. Union Pacific mastermind Thomas Durant felt the Pawnee could help make the commemoration of the early achievement of this milestone monumental.

To show off his new toy to various powers-that-be, Durant put together an excursion of dignitaries from government, business and society (including railroad coach magnate George Pullman, future President Rutherford B. Hayes and several U.S. senators and congressmen) to ride the rails from Chicago west to the 100th Meridian. Durant planned nothing short of a traveling party with plush accommodations, the finest of wines, gourmet meals, lively entertainment—the works. What better way to entertain his privileged guests than to showcase performances by the very same Pawnees who were helping to build the railroad?

On October 23, the visitors settled just west of North’s home base of Columbus, where a huge tent city had been erected. Each tent was comfortably furnished with hay mattresses, buffalo robes, homespun blankets and lighting. Another gigantic tent served as a dining hall.

As evening approached, the lady and gentlemen spectators moved a short distance from the camp to observe a group of Pawnee, performing what was described as a war dance. They witnessed “wild and hideous yells, grotesque shapes and contortions that have ever been witnessed by a civilized assemblage in the night-time upon the plains…,” wrote Union Pacific Consulting Engineer Silas Seymour.

The excursionists were suitably impressed. But even more amusements awaited them.

The next morning’s wake up call consisted of war cries and yells, again courtesy of a number of North’s Pawnee braves who were running through the tent city. A little later, the dignitaries watched a mock battle between Pawnee and “Sioux” (other Pawnee dressed as their enemies). The combatants shot off firearms with blank cartridges and arrows with blunted tips. Observers were astounded by Indian horsemanship and courage.

Most talked about the Union Pacific excursion for years afterward, and newspapers carried stories covering the affair. North and his Pawnees had clearly left a good impression on the railroad. The next year, the Pawnee were promoted from day laborers helping to build the tracks to guards hired as scouts. Thanks to the act of 1866 authorizing President Andrew Johnson to “enlist and employ in the Territories and Indian country a force of Indians, not to exceed one thousand, to act as scouts…,” Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman could hire more effective manpower to guard the Transcontinental Railroad. As a result, Col. Christopher C. Augur had called on North in February 1867 to organize the new Pawnee battalion.

The superintendent of the Union Pacific, C.G. Hammond, also wanted to hire the Pawnee to guard the railroad against Sioux and Cheyenne war parties who were firing on his trains and piling ties on the tracks to block passage. He wrote to House Representative Oakes Ames of his belief that the Pawnee “will go where white soldiers cannot, and have so much experience that they can trace the most intricate movements of the enemy and give notice of hostile parties, always in advance of any information otherwise obtained.” For Hammond, these Pawnees were the most cost-effective means of controlling hundreds of miles of railroad.

The Inspired Showman

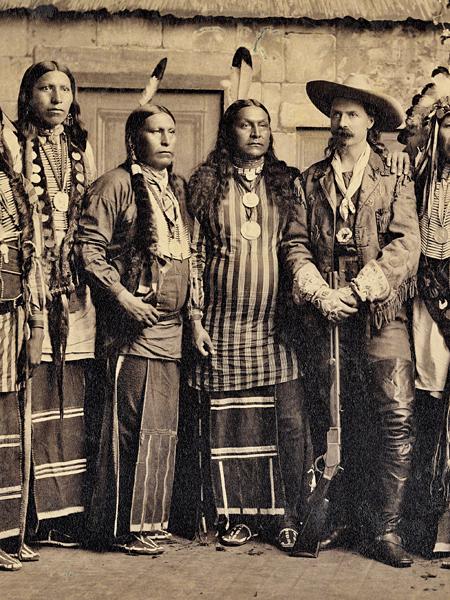

No one can say for sure if Cody ever read any accounts of that unique excursion. What we do know is that, over the years, North and his scouts continued to perform similar exhibitions for other dignitaries, hunting parties and even Union Pacific construction workers. By 1869, Cody and North had become friends and were serving together as scouts and Indian fighters. Over an evening campfire, North likely shared with Cody his story of that first excursion featuring his impressive and entertaining Pawnees.

In any case, Cody was present on June 8 at Fort McPherson when Maj. Eugene Carr’s companies of the Fifth Cavalry, including the Pawnee, performed a military drill. “They were well mounted,” Cody said of the Pawnees, “and felt proud of the fact that they were regular United States soldiers.”

At the dance held later on that night, Cody remarked at how “accomplished” the Pawnee danced, compared to dances he had seen by other Indian tribes.

Within two years, Cody was ready to see if he could make an even bigger show out of these Indian amusements. Cody solicited Pawnee scouts to “ambush” him and a client during a buffalo hunt. The joke almost backfired; the frightened hunter ran to a nearby Army outfit for help, and Cody had to stop the troops from attacking the friendlies.

But Cody was not discouraged. Dressed in his buckskin costume, as he had on that hunt, he continued to tell stories that amused his clients. By the next year, Cody had acquired the skills needed to stage Indian shows across the country.

Cody’s friendship with North continued. In 1877, the two partnered in a Nebraska ranch (it lost money, and they sold it a couple of years later). Ranch life didn’t suit Cody: “There is nothing but hard work on these round-ups,” he noted. But he observed a number of cowboy competitions along the way—roping, bronc and steer riding, shooting and more, and he saw how entertaining these displays of skills could be for an audience.

The pure genius idea of combining Indian exhibitions with cowboy competitions would take six years to develop before Cody brought his show to the arena. In 1883, he unveiled “Buffalo Bill and Dr. Carver’s Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition.” That first show program included an account of the 100th Meridian excursion undertaken by the Union Pacific in 1866.

North again had played a major part in Cody’s creation. He had rounded up the 36 Pawnee performing the Indian roles, he displayed his own riding and shooting talents, and he offered up his home in Columbus to host the rehearsals. In addition, he was undoubtedly responsible for hiring the Pawnee interpreter from the Indian Territory reservation: Gordon Lillie, a 23 year old from Illinois. (This man would soon be dubbed “Pawnee Bill” and put on his own Wild West show; he would even briefly join forces with Cody in 1908.)

The 1883 exhibition didn’t go over so well. Neither Cody nor Carver were businessmen, and several of the performers (including the namesakes) missed gigs because of drunkenness. However, North stuck by his old friend. They got rid of Carver, brought on manager Nate Salsbury, got sober (for the most part) and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West moved into the realms of fame, fortune and legend.

Losing Their Allies

Alas, North’s time spent enjoying the successes of the show was relatively short. In July 1884, while the Wild West was playing in front of a sellout crowd in Hartford, Connecticut, North was performing with several Pawnee when he was suddenly thrown from his horse. An Indian riding behind him tried to veer off, but there wasn’t enough time. The mount stomped on North’s back, breaking seven ribs and causing severe internal injuries.

For days, doctors believed North was on death’s door—but he fooled them. He not only survived the incident, he went back to work for Cody (behind the scenes only; his performance days were over).

But the injuries had weakened his system. In early March 1885, North became ill in St. Louis, Missouri. By the time he returned home to Nebraska, he was suffering severe asthma attacks. In the late afternoon of March 14, a few days after his 45th birthday, Maj. Frank North shuffled off this mortal coil.

Life with the show took a turn for the worse for the Pawnee as well. Within three months of North’s death—maybe it was coincidence, maybe not—Cody hired famed Lakota Sioux Chief Sitting Bull for the show. The aged warrior only spent one season with Cody, but the experience marked a shift in the program: the showman began replacing the Pawnee performers with Sioux. In Cody’s mind, why not showcase real Sioux in “re-creations” of famous Indian battles that involved the Sioux?

Within 15 years, the Pawnee population had shrunk to 633 as

the tribe was decimated by disease and poor living conditions. That would have bothered North—a lot. He probably wouldn’t have cared

that Cody’s historical star eclipsed his own. But without North, his Pawnee scouts and especially the 1866 excursion performances hosted by

the Union Pacific, William F. Cody might have been stuck telling stories around campfires.

Additional reading: Mark van de Logt’s War Party in Blue (University of Oklahoma Press) tells the story of Frank North and the Pawnee Scouts.

Sidetracks

The date was July 1, 1862, and the country was consumed by the blood and thunder of the Civil War. Almost lost in the news of the day: President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act, which set in motion the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad.

The Act also incorporated the Union Pacific Railroad, which means the Union Pacific is celebrating its 150th birthday this year. Most of the commemorative events will be held in towns west of the Mississippi, where the bulk of the railroad’s operations still run.

Museums are taking notice too. This year, the entire first floor of the Union Pacific Railroad Museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa, has been transformed into an exhibit sharing the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. The museum is also hitting the rails with a traveling exhibit that will share the passenger experience through artifacts and a 65-inch touch video screen with a map showing the Union Pacific system from 1869 to the present. Meanwhile, photographs by the man who was present at the launch, A.J. Russell, are on exhibit at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska,

through September 16.

Shared here is a calendar of towns celebrating the Union Pacific’s 150th birthday:

July 6: Pocatello, ID

July 8: Boise, ID

July 10: Spokane, WA

July 13-14: Portland, OR

July 13-19: Omaha, NE (screenings of 1939 film Union Pacific)

July 18-29: Cheyenne, WY (Cheyenne Frontier Days)

July 24: Salt Lake City, UT (Days of ’47 Parade)

July 24: Omaha, NE (“Great Big Rollin’ Railroad” Competition Judging; contest ends July 1)

Aug. 9-19: Des Moines, IA (Iowa State Fair)

Aug. 24-Sept. 3: Grand Island, NE (Nebraska State Fair)

Sept. 7-8: Boone, IA (Pufferbilly Days)

Sept. 9: Ames, IA (Ames Whistle Stop)

Sept. 14-16: North Platte, NE (North Platte Rail Fest)

Sept. 22: Ogden, UT

Sept. 23: Elko, NV

Sept. 26: Sparks, NV

Sept. 28-30: Sacramento, CA

Oct. 27-28: Houston, TX

Visit UP150.com for the updated calendar

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Museum & Grave –

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Andrew J. Russell (American, 1829-1902) Collection, Union Pacific Railroad Museum –