Successful literary collaborations are rare. A few exceptions can be found, such as Mark Twain & Charles Dudley Warner (The Gilded Age), Charles Nordhoff & James Norman Hall (Mutiny on the Bounty), Lou Abbott & Bud Costello (“Who’s On First?”), Randy Roberts & James Olson (A Line in the Sand), and they usually involve just a single genre.

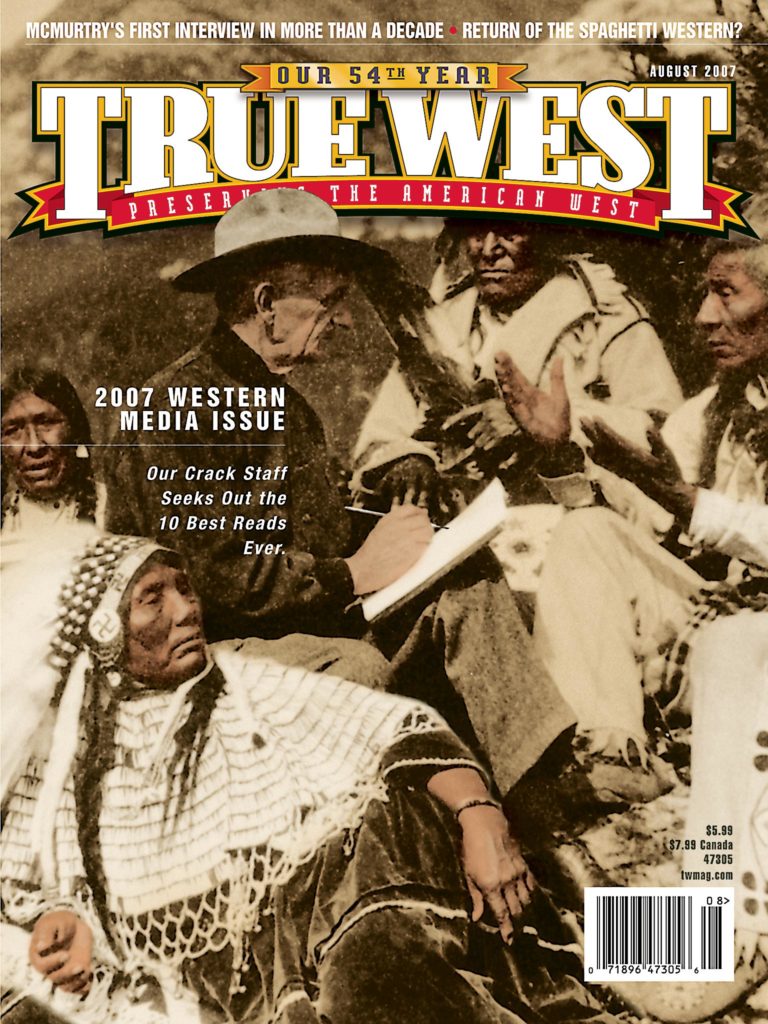

Successful literary collaborations are rare. A few exceptions can be found, such as Mark Twain & Charles Dudley Warner (The Gilded Age), Charles Nordhoff & James Norman Hall (Mutiny on the Bounty), Lou Abbott & Bud Costello (“Who’s On First?”), Randy Roberts & James Olson (A Line in the Sand), and they usually involve just a single genre.

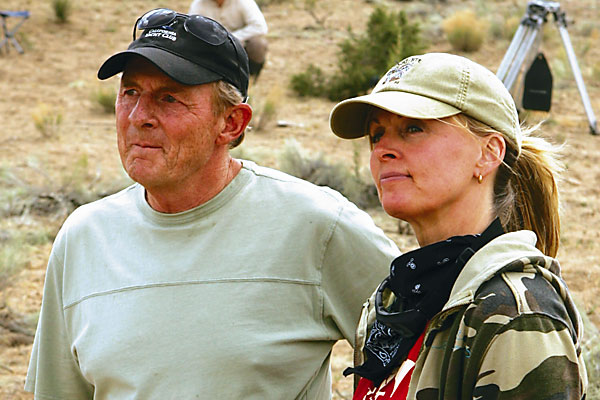

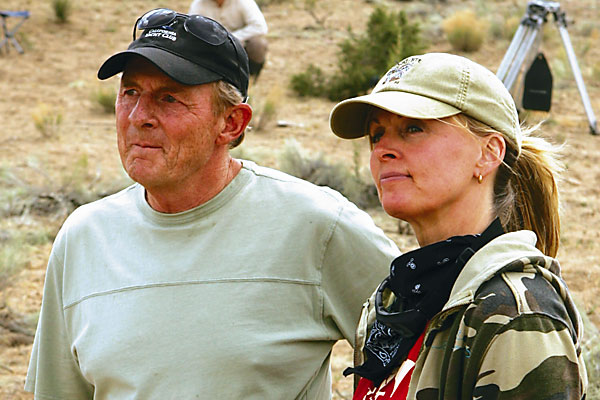

Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana have mastered two mediums—fiction (the novels Pretty Boy Floyd and Zeke and Ned) and film (their Academy award-winning screenplay for Brokeback Mountain, adapted from Annie Proulx’s short story).

While working on the set for the upcoming CBS miniseries, Comanche Moon (which they’ve adapted from McMurtry’s novel, a prequel to the hugely successful Lonesome Dove), they granted True West this interview—McMurtry’s first in more than a decade.

TW: Diana, your short story, “White Line Fever,” is set in the contemporary West and shows a remarkable empathy with a pregnant girl who strikes out on her own to make a new life in Arizona. On the novels and screenplays you’ve collaborated on with Larry, do you look immediately to the female characters involved or are you drawn to the males, as well?

Diana: Larry seems to feel I have an affinity for the male characters in projects we cowrite, but I think that’s because he feels more for women characters. When I create fiction, I can’t recall that I feel more drawn to the men; what I do feel is that I am the character I happen to be writing. I feel whatever it is they’re feeling, as if I am the man or the woman or the child, whatever sex or age the character happens to be.

Trying to explain where fiction comes from is difficult, if not impossible. It comes from some obscure place in one’s imagination. I just know that when I’m engaged in the act of fiction writing, the world I’m creating is as real to me—sometimes more real—than the world around me.

TW: When do the two of you decide to work on projects together? What decisions are involved? Do both of you get an equal vote as to what works and what doesn’t?

Larry: It’s a totally democratic process. In essence, for us, it’s meant taking what comes our way. About the only job we’re turned down was The Return of Rin Tin Tin, and if it should come around again, which it might, we’d probably take it.

Screenwriting jobs don’t grow on trees, no matter how popular you’re considered to be. We avoid purely speculative jobs that are not likely to be movies no matter how good the script—but we consider ourselves lucky to have been offered projects that we can execute effectively as screenwriters—and see them get made.

Diana: Ditto as to most of what Larry said, except we don’t take everything that comes our way. There have been several projects I wanted to do that he simply batted away … except for Brokeback Mountain. I insisted he read the short story, although he doesn’t read short fiction (because he says he can’t write it).

When Larry writes alone, he is much more elaborative in his prose. When he writes with me, however, it’s much more skeletal. I take his pages (usually five a day) and fill them in, delete, add pages, add narrative … then print my pages, which he gets in the evening and has for his morning writing. We do that, every day, until we have a first draft.

Most of the time, it’s totally democratic, but we’ve had some Olympic-sized arguments about specific things—like the ending for Pretty Boy Floyd. Larry says he has no memory of that, but I think it’s because he lost that one.

TW: I don’t know that it’s true Larry can’t write short fiction—Comanche Moon clocks in at only 700-plus pages. That’s short by the standards of some of Larry’s novels, and certainly compared to War and Peace.

Larry: I’ve written several books shorter than Comanche Moon—including the very slender When the Light Goes, just published. But they aren’t short stories or short fiction. The only short story I’ve ever written, published in the Texas Quarterly long ago, is called “There Will Be Peace In Korea.” Tommy Lee Jones has done a fine reading of it on audio book.

Diana: Short stories are much more demanding than novels; they require a kind of precision not necessary in long-form prose. It’s easier to meander around in a novel, certainly. Larry, basically a wanderer himself, enjoys the more forgiving form of a novel.

TW: For the miniseries, did you have to cut any major characters or plot lines for the series?

Diana: It wasn’t so much that we had to give up major characters or story lines; it was that the last part of the novel is so unrelentingly grim that we found it necessary to newly imagine a large portion of Part Three of the miniseries.

TW: A couple of decades ago, in his book of essays on Texas, In A Narrow Grave, Larry wrote, “The figure of the Westerner is gradually being challenged by more modern figures. At the moment, the Secret Agent seems to be dominant.” James Bond is still with us. Last year, he made a big comeback in Casino Royale. The Westerner, in one form or another, is still very much with us—whether in your novels, in the success of HBO’s Deadwood and in films as varied as Brokeback Mountain, Open Range and The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada. Do you think the Westerner will continue to have a future? If so, in what ways will he or she have to adapt?

Larry: I don’t think much about the figure of the Westerner. There’s a good piece in the Spring 2007 issue of the Claremont Review of Books on myself and the rest. It’s by Douglass Jeffrey. It’s good. Give it a look.

Diana: The Westerner will always be with us, in one form or another, since [he’s] such a vital part of America’s history. The notion of an adventurous loner, free of restriction, a risk-taker, someone who lives by the seat of his pants, so to speak, is integral to the romantic notion, right or wrong, of what it means to be a man in this country that it continues to exist in both literature and film: war stories; spy stories; stories about space and astronauts; even historical works, as in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator; or the neurotic criminals in The Sopranos and even the couple in Mr. and Mrs. Smith—a sort of contemporary version of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (but with the female counterpart much more prominent, active and “modern” than Etta Place, as embodied by the Angelina Jolie character). The Westerner will never disappear entirely from our consciousness. As Larry himself [has] said, he initially wrote Lonesome Dove as an anti-mythic Western—but readers everywhere read it, loved it and embraced the myth even tighter than before.

TW: Between fiction, film and TV, you two are becoming a light industry. Besides Comanche Moon, what are you working on for the immediate future?

Diana: We’re working on Boone’s Lick, a novel of Larry’s that was published in 2000, for Tom Hanks to star in, tentatively scheduled to begin filming later this year, as well as two-hour pilots for ABC and FOX … it’s good to be busy!