The first white men in the Rocky Mountains were trappers who became known as Mountain Men, arriving decades before Lewis and Clark.

The first white men in the Rocky Mountains were trappers who became known as Mountain Men, arriving decades before Lewis and Clark.

Many were of French descent and came by way of Canada. These men were loners who lived off the land and trapped beaver—the Mountain Man’s gold. They lived more like the Indians they married and with whom they traded rather than their own people. An insatiable desire to see what lay beyond the horizon and to find new streams to trap made them explorers, as well. Their annual Rendezvous provided them the time to not only trade and sell their furs but to develop virtually their own language and culture of storytelling, frolicking, drinking and dancing.

Hundreds of the Mountain Men swarmed over the vast areas of the West from 1800-40, and the beaver were virtually eradicated, much like the buffalo would be 40 years later. The demand around the world for stylish top hats constructed of beaver “wool” made the trapping and trading of beaver pelts profitable, until silk replaced it.

The Mountain Men then turned to other occupations or made homes among the Indians. Some, the ones remembered today, were employed as scouts and guides for government exploration and surveying parties, the military, hunting expeditions and westward moving immigrants. Eventually, many of these men became farmers, ranchers, businessmen and, except for a very few, moved into anonymity.

Englishman George Frederick Ruxton gives a clear word-picture of the typical Mountain Man: “The costume of the trapper is a hunting shirt of dressed buckskin, ornamented with long fringes; pantaloons of the same material, and decorated with porcupine quills and long fringes down the outside of the leg. A flexible felt hat and mocassins clothe his extremities. Over his left shoulder and under his right arm hang his powder horn and bullet pouch…. Round the waist is a belt, in which is stuck a large butcher knife in a sheath of buffalo hide, made fast to the belt by a chain or guard of steel, which supports a little buckskin case containing a whetstone. A tomahawk is also often added; and, of course, a long heavy rifle is part and parcel of his equipment. I had nearly forgotten the pipe holder, which hangs round his neck.”

Ruxton’s description is supported by the art of Alfred Jacob Miller, one of the few artists to paint the Mountain Men from life in their heyday and in their mountain environment. The clothing varied little from that worn by the Indians. The white men seem to have preferred a brimmed hat to the coonskin hat of the Eastern frontier or the Indians’ more decorative, but less protective, head gear. Sometimes the men concocted all sorts of fur and cloth wraps for their heads. Hats seem to have been a favorite for variety and innovation throughout the Old West.

We like to picture the Mountain Man with a full beard. (No self-respecting re-enactor today would dare not have a beard.) Miller and other early artists invariably painted them with long unkempt hair, often with a mustache, but rarely with a beard. One wonders why these men would take the time to shave frequently in the wilderness. Later artists, who never saw them in life, painted them with the full beard.

As to the character of the Mountain Man, Ruxton was not exactly kind. “Their wish is their law … people fond of giving hard names call them revengeful, bloodthirsty, drunkards, gamblers…. Their animal qualities are undeniable. Strong, active, hardy as bears, daring, expert in the use of their weapons, they are just what uncivilised white men might be supposed to be in a brute state.” And yet, many of the Mountain Men became peaceable citizens when civilization came.

Photography arrived in America in the early 1840s, at the very end of the Mountain Man era. The existing photographs are portraits of old men, taken long after they had retired from their trapping days. Still, the rugged life they had lived and their strong character are visible in these photos.

William Bent

Historian Dan Thrapp called William Bent “one of the frontier’s major figures.” Born into a prominent St. Louis family, Bent turned to trading on the Arkansas River after first trapping in the mountains of the Southwest. His fort, constructed in 1835, became the principal trading and meeting point for trappers, traders and Indians. Bent was strongly allied and influential with the Cheyennes. His three sons, from Cheyenne mothers, were caught in the tragic Indian-white relations of the time, all three being at the Sand Creek massacre—two with the Cheyenne and one with Chivington. William’s partner and brother Charles was the first governor of New Mexico after its conquest by the U.S., and he was slain in the Taos uprising of 1847. This photo appears to be one of only three known: two portraits, plus a distant shot of Bent with some of his Cheyenne friends. Bent died in 1869.

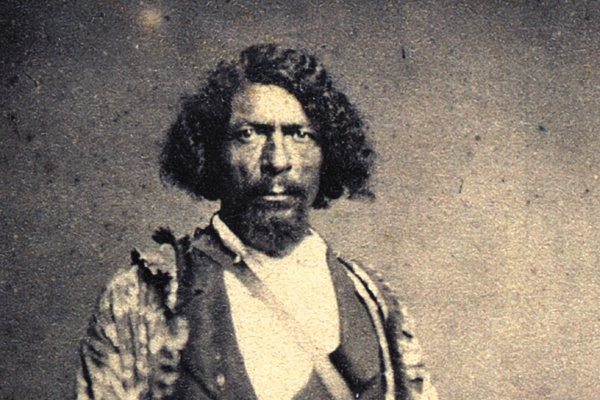

Pierre, Rocky Mountain Trapper

This sketch by Alfred Jacob Miller depicts Pierre as a young, smooth shaven man, with his mule close by. Pierre wears fringed buckskins and a wide brimmed hat.

James Baker

A late-comer to the fur trade, Jim Baker joined the American Fur Company in 1838 at the age of 18. After two years of trapping in the Green River Country and a brief return to Illinois, he joined with Jim Bridger’s band of trappers. Baker was adopted into the Shoshoni tribe and became known as the “Red Headed Shoshoni.” After his adventures in the mountains and service with the military as interpreter and guide, Baker settled in the Denver area following the 1859 Colorado gold rush. This photograph was taken in Denver in the early 1880s, when Baker would have been about 64. As his biographer Nolie Mumey put it, “Baker was as rugged as the mountains where he had spent most of his life. His wrinkled face and forehead contained lines chiseled by nature; his many adventures were clearly written on his bronzed features.”

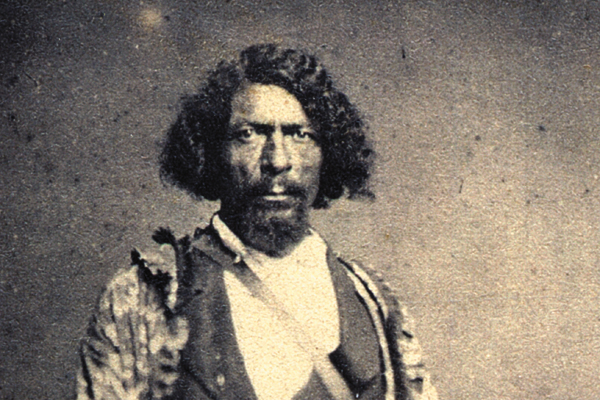

Mariano Medina

Although they welcomed the Mountain Men in Taos and Santa Fe, few Mexicans were trapping beaver and trading furs in the mountains. One exception was Mariano Medina, a native of Taos, who became a successful Mountain Man in the company of Americans. He roamed much of the Rocky Mountains and eventually settled in northern Colorado. As with most of the Mountain Men, he took an Indian wife. Medina is described as a small man, spry and active, with black hair. His dress varied from the American Mountain Man, leaning toward the Mexican fashion. This original photograph is from a stereoview, probably dating circa 1870. Stereoviews were commercially produced for sale, indicating that Medina had acquired some recognition as a pioneer. Or maybe his image was sold because he presented a colorful appearance.

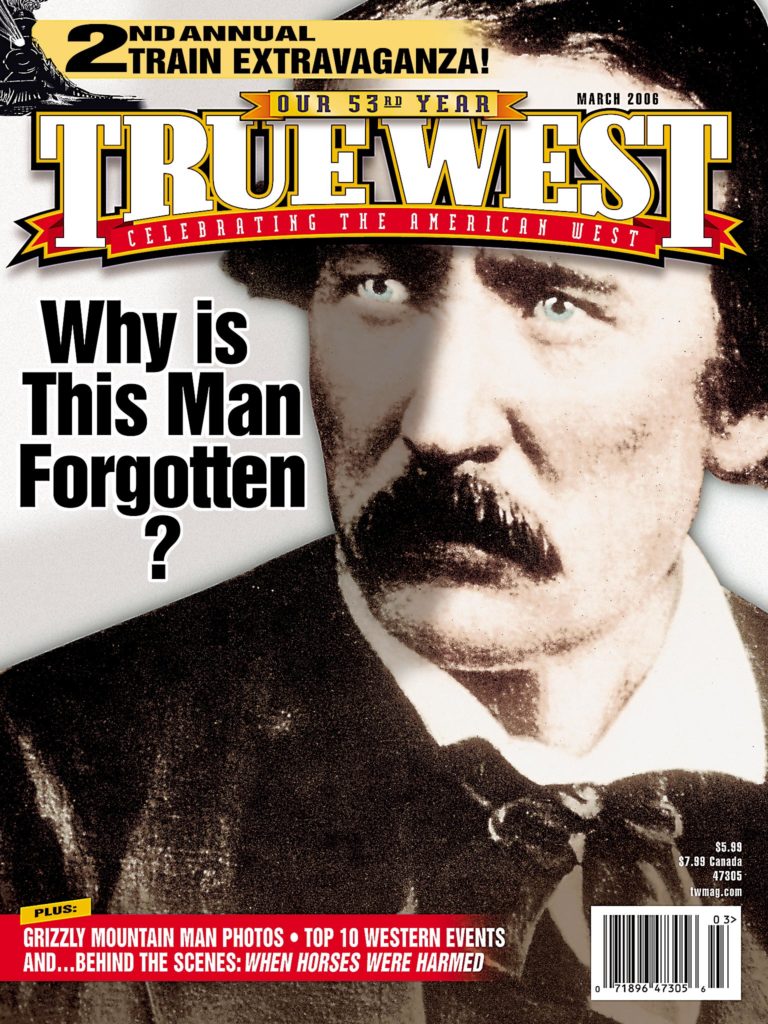

James Bridger

Next to Kit Carson, perhaps the most famous Mountain Man is Jim Bridger. He was only 18 years old when he joined the Ashley fur trading venture in 1822. His experience in the fur trade (including encounters with grizzly bears, Indians and Mormons) was followed by service as a guide for numerous expeditions. His knowledge of the Rocky Mountains was said to be unsurpassed. But Bridger was also famous for spinning unbelievable, but sometimes true, tales of the Yellowstone Country. He married three women from the Flathead, Ute and Shoshoni tribes, fathered several children and retired to his farm in Missouri, dying there in 1881 at the age of 77. This photo, one of only two known images, is said to have been taken circa 1866, when he would have been 62 years old.