On September 20, 1886, 383 men, women and children of the Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apache bands arrived in Jacksonville, Florida.

On September 20, 1886, 383 men, women and children of the Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apache bands arrived in Jacksonville, Florida.

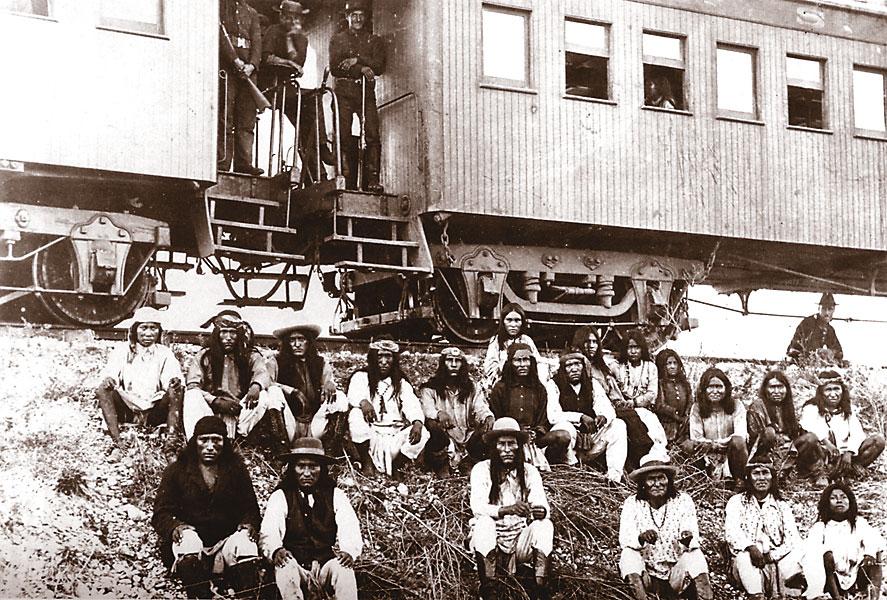

They were on their way to prison in St. Augustine aboard a special train of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe line. When they detrained to walk to the ferry that would carry them across St. Johns River, they attracted hundreds of onlookers just as they had at each stop on the 2,000-mile route from Holbrook, Arizona.

As elsewhere along the way, the mood among the locals resembled a crowd at a carnival sideshow. Jason Betzinez, a member of the Warm Springs band, later said, “we were stared at by throngs of people at every station where the train stopped. Apparently they regarded us as some kind of wild animals.”

A reporter from Jacksonville’s Times-Union wrote this about the new arrivals. “A more dirty, disgusting, strong scented mass of humanity never alighted from a train in Jacksonville. And the stench that came from the cars was worse than ever came from a nest of ten year polecats.” He did not report on why the train cars and the prisoners smelled that way.

They had made the two-week trip from southern Arizona with the windows of their 10 coaches nailed shut. Fresh air couldn’t enter the cars, but clouds of black smoke from the engine did. Their sanitary facilities consisted of buckets that were rarely emptied. Unfamiliar with the tins of food they received as rations, the Apaches either refused the contents or they ate them after they had spoiled.

Salmonella, choking smoke, strong odors, heat and the swaying motion of the cars made people sick. The results combined with urine and feces from the overflowing buckets until the floors were awash with the mix. Even after hosing down the cars at some stops, the stench remained overpowering. In spite of that, the captives were told that anyone who opened a window would be shot.

Most of these Apaches had been living peacefully, trying to farm the parched lands set aside for them on the San Carlos and White Mountain Reservations. Rough country made the reservation boundaries impossible to seal off, however, and some young men took advantage of the system. When cold weather came, they slipped into their families’ camps and received govern-ment rations. In the spring, they left and went back to stealing the White settlers’ livestock.

Removing the warriors’ families to the other side of the Mississippi River provided a solution. Governmental suspicion and the Arizona settlers’ animosity ran so deep that even Apaches who had scouted for the U.S. Army were sent east as prisoners. Still wearing their blue uniform blouses, they and their families rode with the people they had helped the soldiers hunt.

The Army scout Chatto arrived in St. Augustine with 13 of his people three days before this group. Soldiers had stopped his train on the way back from Washington, D.C., and turned it around to deposit him, under guard, in St. Augustine. To the end of his life, he wore safety-pinned to his coat the silver peace medal awarded to him in Washington.

Castillo de San Marcos

The Apaches’ destination was a 200-year-old stone fort that hulked above the marshes on the western shore of Matanzas Bay like a relic from medieval times. Beyond the marshes stretched cypress swamps, scrub oak thickets, pine barrens and a formidable expanse of Spanish bayonet and saw-toothed palmettos that sheltered snakes and scoffed at axes.

The Spanish called the fort Castillo de San Marcos, and its basic design was elegantly simple. Its inward-sloping stone walls formed a square with an arrowhead-shaped bastion at each corner. A gull’s-eye view was that of a four-pointed star. A deep moat surrounded it. A drawbridge and sally port served as the fort’s only entrance. By the mid-1800s, the moat was dry and stock grazed there.

In 1586, Francis Drake began the tradition of sacking St. Augustine. Raids by other sea-going entrepreneurs followed. When English pirates burned the town yet again in 1668, the Spanish decided they needed better protection than their rotting palisade of palm logs.

In 1671, they built kilns to fire a quick-setting lime from oyster shells. On nearby Anastasia Island, laborers cleared the dense brush covering bedrock formed a million years earlier when the Atlantic Ocean covered Florida. The sedimentary limestone was studded with delicate pink and lavender coquina shells. The workmen rough-cut two-by-six-foot blocks of coquina, then dressed them out and transported them to the site.

The project employed Spanish stonecutters, blacksmiths, teamsters, quarry men, lime burners and overseers. The rest of the work force consisted of Guate, Timicua and Apalachee Indians, Spanish soldiers and convicts, black slaves, free blacks and mulattos, and English prisoners of war. For 90 years, construction started, stopped, then started through pirate raids, famine, illness, marrow-stewing heat, hurricanes, labor shortages, mutinies, lack of funds and British incursions.

By 1736, James Oglethorpe had extended his Georgia colony’s border to within 35 miles of St. Augustine. To guard against British ships lobbing cannonballs into the fort, the Spanish added eight arched

vaults along the east curtain. Workers leveled off the tops of the vaults by filling the crevices between them with coquina shells and tabby mortar, and then tamping it down. The resulting terreplein or gun deck would hold heavy artillery. Arranged around the courtyard inside were latrines, guardrooms, smithy, storerooms, chapel, magazine, kitchens, a jail and soldiers and officers’ quarters.

When Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1821, the Americans renamed the castillo Fort Marion in honor of the Revolutionary hero, Gen. Francis Marion. By 1886, Fort Marion was falling into ruins. Appropriations for its repair had been stalled in a Senate committee for two years. Perhaps President Grover Cleveland wanted to force the legislation to a vote when he chose Fort Marion over the larger Fort Pickens in Pensacola.

Fort Marion had served as a prison before. In the late 1830s, it had held Seminole and Miccosukee prisoners of war. In the 1870s, people of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Caddo, Kiowa and Comanche nations were kept there.

Pestilence in St. Augustine

In April 1886, the Chiricahua Chief Chihuahua and 77 of his people arrived. When they had boarded the train in Holbrook, no one told them where they were going, how long they would stay or what they would need, so they brought everything they had. Their baggage consisted of “square packages tied with ropes; black tin cans and buckets and pots; packages of splendidly tanned and highly ornamented skins; bundles of dried meat, sacks of meal, coats, odd-looking blankets, and a variety of other plunder.” In St. Augustine, Negro porters jeered as they loaded the “plunder” onto wagons for transport to the fort.

The Times-Union reporter described Chihuahua’s people as they detrained: “dirty, ragged, half-clad, and with long unkempt locks of coarse black hair flying loose about their heads. In their eyes, they were typical savages. First came the men, each with shoulders and head wrapped in a blanket and all marching with expressionless faces and stately gait; then came the young bucks with less dignity and fewer blankets, as well as fewer clothes of any kind; then straggling along one by one, came the young women, girls and children … lastly came the old women, each hugging a baby or bundle.” As they filed across the fort’s drawbridge, the loud squeal of the windlasses pulling it up behind them must have startled them.

The men and boys were given fishing tackle and instructed to haul their rations from the bay. Apaches, however, believed they would assume the characteristics of what they ate, and fish would cause them to become speckled. The taboo extended to snakes, and to the pigs who ate them. The government did not acknowledge the Apaches’ cultural restrictions and continued to try to make fish and pork the basis of their diet.

When asked by the Secretary of War what preparations would be necessary to accommodate 400-500 more prisoners, the fort’s commanding officer wrote back, “Fort Marion is a small place…. Would recommend no more Indians be sent here.” In spite of that, hundreds were rounded up from the San Carlos Reservation. By November 1886, 502 prisoners and their army guards occupied an area encompassing less than an acre.

A number of teachers, including nuns from the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, gave instruction to the children in Math, English and the American way of life. To pass the time, the men played cards and engaged in archery contests and ball games in the dry moat. The women wove baskets and made moccasins and toy models of their cradle boards to sell to the tourists.

Twelve children were born at the fort. Geronimo remained at Fort Pickens in Pensacola, but his pregnant wife, Ih-tedda, was sent to St. Augustine. She named the child Marion. Other babies born there included Chihuahua’s daughter, Coquina; Chief Pedro Juan’s daughter, Marion Juan; and John Loco, son of Chief Loco and his third wife, Clee-hn.

When the army’s Sibley tents arrived, the Apaches were moved from the cavernous bombproofs and up the fort’s only flight of stone steps to the terreplein. There they settled into their tent camp overlooking Matanzas Bay. A lot of rain falls in Florida. The bricks and mortar of the gun deck where the Chiricahuas slept were almost always wet.

North Florida is cold and damp in winter, and the ocean wind had nothing to stop it from sweeping across the terreplein. The government never got around to supplying clothing for its charges. The Apaches, especially the children, shivered in the same clothes they had been wearing when soldiers loaded them onto the trains in Arizona.

Many of them fell sick with malaria, and 18 died within three months. Even though Fort Marion’s medical officer examined everyone each morning, another government policy exposed his charges to diseases for which they had no immunity. Rather than keeping the prisoners off-limits, the authorities promoted them as an attraction. Hundreds of St. Augustine residents and tourists mingled with the Chiricahuas in their camp on the terreplein. The outsiders added to the overcrowding, and they brought diseases with them.

The Apaches, with an armed escort, were also allowed to go to the beach or roam St. Augustine. Many of them sat for portraits at a studio on St. George Street. They became celebrities of a sort, but they also carried more illnesses back to the fort. Dysentery, bronchitis, malaria, neuralgia and tetanus spread, but the worst of the afflictions was tuberculosis.

Disease, exposure, bad food and the destruction to their way of life took a toll equal to that of the warfare the Apaches had waged for decades. The herbs that the Apaches had depended on for generations were not available, but the eldest healer, Ramon, improvised a water drum by stretching a soaped rag across an old kettle. He led men dressed and painted as G’an, Mountain Spirit dancers, in a ritual intended to drive away evil spirits.

Eventually, newspaper reports of illnesses and deaths at Fort Marion caught national attention. Herbert Welsh of Philadelphia’s Indian Rights Association came to study the situation. His report criticized the conditions at the fort and included outrage over the treatment of the Apache scouts. It stirred up so much public sentiment that the governmental bureaucracy began to react, although with its usual sluggishness.

On April 27, 1887, the Apaches left Fort Marion by train for Mount Vernon, Alabama. Those at Fort Pickens were also sent to Mount Vernon, and Geronimo was finally reunited with his family. The Chiricahuas were freed in 1913, but Geronimo never saw his homeland again; he died in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in 1909.

Lucia St. Clair Robson is the author of Ghost Warrior, the story of Lozen of the Apaches, and Ride the Wind, winner of the Western Writers of America’s Golden Spur Award.

Photo Gallery

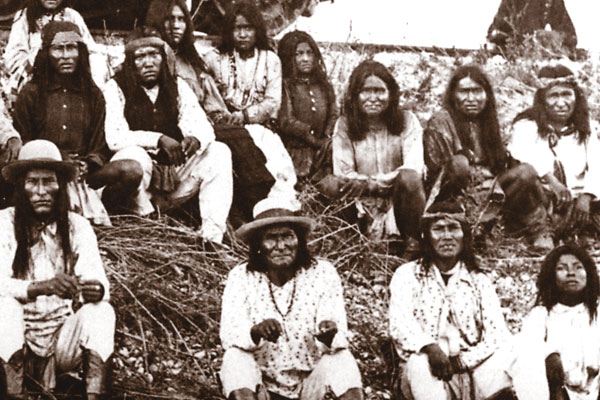

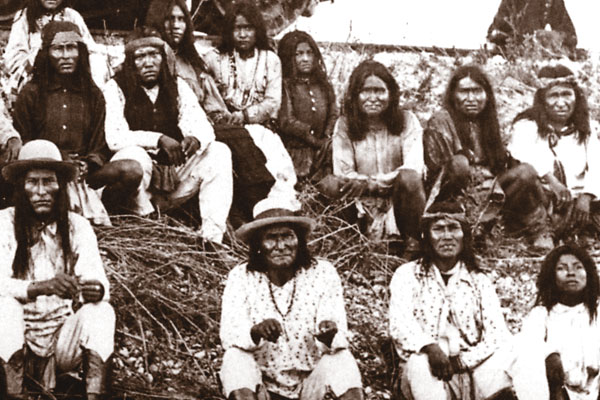

In 1886, nearly 400 Apache prisoners were transported to Florida via train. One band is shown above, with Geronimo seated in the first row, the fourth from left.

– True West Archives –