Under the category of weird but true, the Old West offered enough episodes to fill a sensation-mongering newspaper. Make that 100 newspapers.

Under the category of weird but true, the Old West offered enough episodes to fill a sensation-mongering newspaper. Make that 100 newspapers.

Some of these tabloid treasures involved the quest for love and romance, while others highlighted the grimness of death by hanging. But all of them paint the West as one weird place.

The Lunacy of Love

How to find true love? Men and women ask that question today, just as they did on the frontier. Sometimes the search for a squeeze led to events and people bizarre enough to revisit a century or more later.

Remember Groucho Marx’s wisecrack about never joining a club that would have him for a member? Bad guy Black Jack Ketchum would’ve understood that. After feeling the sting of a woman’s rejection, the hard-drinking outlaw beat himself silly with a pistol and a lariat, only confirming his former paramour’s stellar judgment.

We have to wonder if Phillip “Doboy” Taylor’s girl questioned her own sanity in marrying such a blood-soaked, Texas warrior. Taylor was a major player in the Sutton-Taylor feud, but he found time to get hitched. He held his wedding on horseback on a broad prairie, in case any Suttons showed up to arrest him. Honeymoon? The bride and groom repaired to the Taylor gang’s hideout for some semi-public canoodling.

Bobby Gill and his gorgeous lover Susy Haden, a Creole maiden, suffered the same indignity, according to the Dodge City Times of March 24, 1877. Several drunks, planning to retrieve Gill, rode to Haden’s home and burst in on the couple as they occupied “positions … of such delicate nature as to entirely prohibit us from describing in these chaste and virtuous columns.” In language typical of those Victorian times, the paper reported that the men “dragged [Gill] from the

downy couch.”

While we understand the appeal of solid sack time, we also root for true love, and the stranger the better. The story of Lalu Nathoy, a Shanghai-born Chinese girl, certainly qualifies. Legend has it that her destitute parents sold her, after which she wound up an indentured dance hall hostess called Polly—basically a slave—in Warrens, Idaho, in the early 1870s. Fortune turned when her Chinese owner used her to sweeten the pot in a poker game with saloon owner Charlie Bemis. Charlie won Polly and began keeping domestic with her. They married in 1894. At Charlie’s death in 1922, they’d been together, faithfully, more than 50 years—thanks to some lucky cards in a poker game.

But the elixir of love sometimes proved poisonous, as Tombstone, Arizona, resident Bill Kinsman learned. In 1883, somebody played a practical joke on ol’ Bill, posting a notice in the Tombstone Epitaph announcing Kinsman’s intention to marry May Woodman. An astonished Kinsman took out a blurb of his own, stating that he had no such plans, and that was that. Out of her mind with humiliation, May tracked down Kinsman and shot him dead.

Steve Long, a deputy in Laramie, Wyoming, crossed his woman and paid the ultimate price, too. After discovering that Long, her fiancé, had a part-time job as a thief, she blew the whistle, and vigilantes promptly stretched his neck from a telegraph pole. His gal-pal’s reaction? She erected a monument to the memory of the fellow she’d sent to eternity.

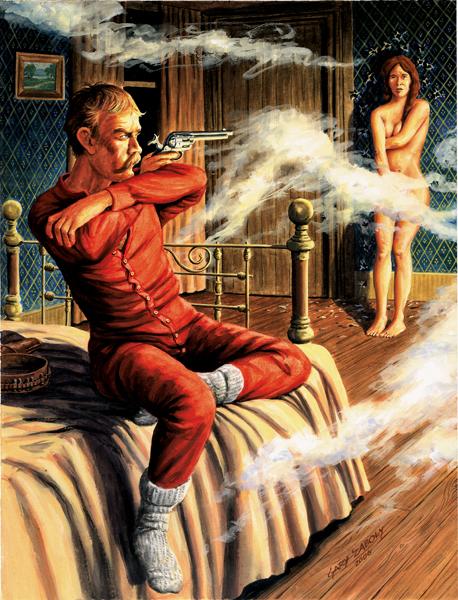

Or take the case of Buckskin Frank Leslie. He was an Army scout during the Apache wars, frontiersmen, raconteur about Tombstone and occasional killer whose serial womanizing, combined with an unquenchable thirst for bug juice, led to some truly memorable nocturnal episodes.

These included the charge that Frank forced his wife, May Killeen Leslie, to stand against their bedroom wall while he outlined her with bullets fired from his .44. Once out of ammo and suitably, ah, prepared, Frank ordered his wife into the marital sack. This strange practice earned May the nickname Silhouette Girl. Mollie Williams, the girl Frank married a few years later, suffered an even worse fate. He shot this “target girl” in the head, killing her.

The legendary soldier and Texas Ranger William Bigfoot Wallace also had one shot at love in his lifetime. It didn’t work out, but it produced a wonderfully strange story.

After falling for a girl in Austin, he got sick and lost all of his hair. Unwilling to allow his gal to see him bald as an onion, Wallace fled to a cave in the mountains to grow his hair back. He had his own special seeding technique. Bigfoot killed bears and rubbed the grease from their carcasses onto his pool-table head, then washed it off with soap and water. “In time, this treatment produced a fine, soft fuzz, or down, on his bare cranium, so he looked like a young buzzard,” wrote Stanley Vestal in his 1942 biography of Wallace. “But at last his hair began to sprout. It was puny and considerable scattered at first. But afore long, it came out thick as a horse’s tail.” One day a friend visited Wallace’s cave with news that his sweetheart had married another man. Bigfoot’s temper rose, along with his young dander, and he made a remark that still resonates for aggrieved bald men today. “I’m glad she’s gone,” he barked. “A woman that can’t wait till a man’s hair grows out, I don’t want.” Bigfoot spent the rest of his life alone, happy and hairy.

Stretching Necks and Belief

Hangings gave the frontier West its best original theater. Nothing could beat a length of rope tossed over a tree limb or creaking gallows for drama, humor, great dialogue and, of course, weirdness.

The trouble with the normal frontier hanging is precisely that word—normal. The bad guy stood before his marble-eyed executioners, the trapdoor swung open and hell gathered in another rascal.

It was a glorious event, don’t mis-understand, a real community festival. But it lacked style. We much preferred hangings that followed no script, in which the whole blasted thing was botched. Call them neck stretchings with a twist.

Take the case of the notorious killer Deacon Jim Miller, who met his end in Ada, Oklahoma, in 1909, when vigilantes lynched him. Evidently hoping to look dapper for the buzzards, human or otherwise, Miller asked to be hanged with his black hat on.

William Fredericks stood on the gallows in California in July 1895, and unlike others facing that fate, didn’t prattle on about God or family. After reading from a paper detailing his crimes, Fredericks offered to sell the list for $100. Those in attendance maintained stunned silence at his incomprehensible hucksterism. Sure, he’d killed two men—a sheriff in Nevada and a bank teller in San Francisco—but who did he think he was, John Wesley Hardin? The megalomanical murderer lowered his asking price to $20. When it became evident the strange auction would end with no sale, the executioners dropped the trapdoor.

The 1878 hanging of noted gunfighter Bill Longley didn’t go so well, which is why we remember it here. First, he sang “Amazing Grace” in his Lee County, Texas, cell prior to climbing the death platform. That alone could generate enough community disgust to wish for a man’s demise. Then, when he dropped to the bottom of the scaffolding, Longley’s knees hit the ground, preventing the requisite neck snapping. They had to do the whole darn thing over again.

These mulligans happened with relative frequency in the Old West.

Theodore Baker’s two hangings took place months apart. The first occurred when citizens of Colfax County, New Mexico, swung him from a telegraph pole for killing a farmer. He was cut down before his heart stopped and shipped to the New Mexico Penitentiary, where, on May 6, 1887, experts did the job right.

But Baker left a lasting legacy when he described the experience of being hanged: “My senses left me for a moment and then I awakened to what seemed to be another world. The sensation was that everything about me had been multiplied a great many times. It seemed that my five executioners had grown in number until there were thousands. I saw what seemed to be a multitude of animals of all shapes and sizes.”

We know the identity of those animals, too—the snaggle-toothed humans surrounding him.

Then there were the folks who didn’t get a second drop. The first was bad enough.

Consider Edward Fulsom, who met death in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in 1881. So skinny was this murdering horse thief that the drop failed to snap his neck, after which onlookers waited an agonizing 63 minutes for his heart to stop.

The grossly overweight John Thornton, also hanged at Fort Smith, had the opposite problem. When he sailed through the trapdoor, his head nearly came off. It remained attached to his massive torso only by a few stubborn tendons.

The last words of the doomed usually ran along two tracks. Either the fellow folded up like a cheap suitcase and apologized, always dull as a derby in our book. Or he savaged his executioners, which we much prefer.

Jack Gallagher stood before vigilantes in Montana in 1864 without a shred of remorse. In his last words, Gallagher barked, “I hope forked lightning will strike every strangling … of you.” History doesn’t record the missing words. Fill in your favorite obscenity.

Martin Ubillos seemed delighted to be meeting his executioner in Yuma, Arizona, in 1905. As the sheriff slipped on the noose, Ubillos smiled, prompting the sheriff to ask what was so funny. Glancing up the hill at Yuma Territorial Prison, his hellish former home, Ubillos said, “You have to go back up there. I don’t.”

The soon-to-be-dead often proclaimed innocence, explained their crimes or said goodbye—to mothers, prostitutes, old pals. Most of these remarks missed oratorical eloquence by a horseback mile. But a few put butterflies in your belly.

In Oregon in 1850, five Cayuse Indians, including Chief Tiloukaikt, were hanged for the murder of missionaries Narcissa and Marcus Whitman. The Indians had surrendered to prevent retribution against their tribe. Tiloukaikt explained his actions, saying, “Did not your missionaries teach us that Christ died to save his people? So we die to save our people.”

When it comes to final verbal exertions, don’t forget John Childers. He was an ordinary throat-cutter whose only memorable utterance occurred after the noose went around his neck in Fort Smith, Arkansas, in 1873. Standing beside Childers on the platform, Marshal John Sarber promised the outlaw a reprieve if he’d roll on his criminal pards. But he refused.

“Didn’t you say you were going to hang me?” asked Childers, defiantly.

“Yes,” Sarber said.

“Then why the hell don’t you do it?”

He did. On his feet or swinging in mid-air, John Childers was a stand-up guy.

His death scene even acquired a Biblical air when, as Glenn Shirley described in his book, Law West of Fort Smith, a tremendous clap of thunder shook the earth as the trapdoor swung open and lightning burst from the heavens. A terrified woman shouted, “John Childers’ soul has gone to hell! I done heerd the chains a-clankin’!” Then a hard rain drenched everyone in the crowd, as if cleansing them of the sin of curiosity.

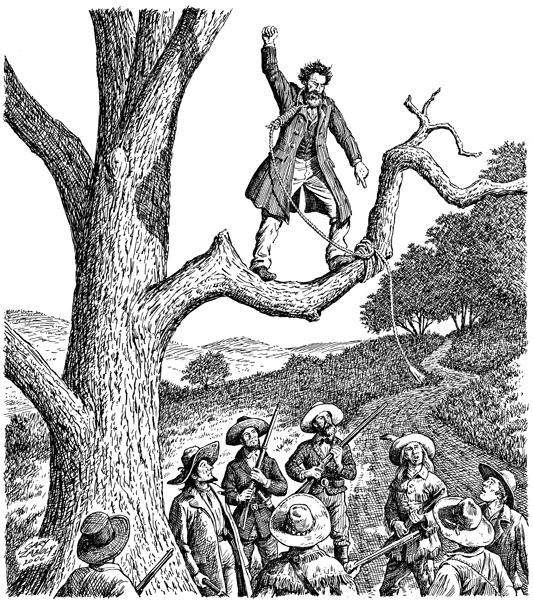

But no bad guy went down with more style than John Langford, who died near Pond City, Kansas, in 1869. With vigilantes all around, his fate certain, the defiant Langford told his executioners to back off, that he’d hang himself. According to a Leavenworth newspaper, he pulled off his boots, fastened the rope around his own neck, climbed a tree and jumped, depriving his killers of a sublime pleasure. Prior to this, the vigilantes had asked Langford if he’d like to make peace with his Maker, to which he replied that “if he had a Maker, he was a damned poor one.” He then told the vigilantes that he’d “meet them all in hell, but none of them should gain admission except with hemp ropes ornamenting their necks.”

Langford is our kind of guy. He helped make the Old West very weird.

Tucson-based Leo W. Banks has been writing about the West, and laughing about its weirdness, for 30 years.

Photo Gallery

– All illustrations by Gary Zaboly –