Alaska and the Canadian Northwest remain dangerous country. People get eaten by bears. They die of exposure. Probably a few are trampled by hordes of tourists departing cruise ships and are buried underneath the mud, never to be seen again.

Alaska and the Canadian Northwest remain dangerous country. People get eaten by bears. They die of exposure. Probably a few are trampled by hordes of tourists departing cruise ships and are buried underneath the mud, never to be seen again.

No surprise then that The Bride and I have been in Alaska less than 15 minutes before the first injury occurs. The Bride has sprained her ankle, stepping off the curb while loading her backpack into the shuttle at Juneau International Airport.

“Bummer,” says the receptionist at the emergency clinic.

The idea, of course, was to follow the route of the Klondike Stampeders, the guys and gals of 1898 and the great gold rush, and avoid Robert Service poetry.

So much for hiking the Chilkoot.

Juneau, You Know

Juneau wasn’t on that trail. Its rush came 18 years earlier when gold was discovered in 1880, and the state capital is a good place to brush up on Alaska history. An excellent first stop is the Alaska State Museum, which has been housing artifacts since 1900. For the mining experience, check out the Last Chance Mining Museum & Historic Park and the AJ Mine/Gastineau Mill Enterprises, Southeast Alaska’s lone hard-rock gold-mine tour. You might even hear someone reciting Robert Service verse. And the historic Alaskan Hotel & Bar is a great place to wind down, although those stairs can be hard on a sprained ankle.

Bum ankle or not, our destination is Skagway, so we hop (literally, in The Bride’s case) aboard the Alaska Marine Highway System. The ferry has been shuttling folks since 1963, providing Inside Passage service from Skagway to Bellingham, Washington, and Prince Rupert, British Columbia. It’s about 51?2 hours from Juneau/Auke Bay to Skagway, with a pit stop in Haines, giving The Bride time to rest her ankle and watch orcas.

A Short History

Our trip started in Seattle before taking an Alaska Airlines jetliner to Juneau and its deadly curbs. After all, Seattle was the supply center and a major embarking/

debarking port for the horde of stampeders. That history is dutifully recorded at Seattle’s Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park, while the surrounding Pioneer Square area remains interesting, historic and exciting.

A Tagish Indian named Skookum Jim found paydirt on a Klondike drainage in Canada’s Yukon Territory on August 14, 1896. Partner George Carmack took the largest claim for himself, arguing that officials would never let an Indian record the discovery claim. Jim and Dawson Charlie took the lesser claims. Word spread quickly, the creek was renamed Bonanza and by Christmas, some 3,000 miners had flocked to the Klondike. In the summer of ’97, steamers such as the Portland and Excelsior brought gold to the States.

The rush was on! Many Klondikers took the water route, steaming from Seattle to St. Michael, Alaska, on the Bering Sea, and then up the Yukon River to Dawson City, Yukon Territory. Others journeyed by land across Canada—and this was before the Alaskan Highway was built. Most prospectors, however, steamed up the Inside Passage to Skagway or Dyea, where their adventures truly began.

Wild About Skagway

Even in the summer, Skagway is a fairly sleepy town—until cruise ships arrive. Then you get a feel for what it was like during the stampede. About the only thing missing is Skagway’s notorious Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith swindling newcomers. Soapy’s here, of course, buried in the Gold Rush Cemetery. So is Frank Reid.

In the summer of ’98, vigilantes got tired of Smith’s rule and held a meeting. Smith went to the docks to break it up. There he met Frank Reid. Words were exchanged. So was lead. Within minutes, Smith and Reid, who, according to the headstone in the cemetery “gave his life for the Honor of Skagway,” lay dying.

Yet the story of Soapy Smith is only a small—but quite popular—chapter in Klondike history. There was much more to this adventure, and Skagway is full of it. The town is home to its own version of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park. Skagway’s unit includes a seven-block section of town, plus the nearby Dyea townsite, part of the White Pass Trail and 17 miles of the legendary Chilkoot Trail.

Historic sites in downtown Skagway include the Arctic Brotherhood Hall, the Mascot Saloon, the Golden North Hotel and Jeff Smith’s Parlor. You’ll probably hear someone reciting a Robert Service poem. Unavoidable, it seems. With luck, though, the White Pass and Yukon Railroad will drown out any poetry.

The toughest stretch for many stampeders came early, either on the Chilkoot Trail out of Dyea, about nine miles north of Skagway, or the White Pass Trail from Skagway. The Chilkoot was one brutal hike, too steep for pack animals. White Pass was brutal for beasts. More than 3,000 animals, overloaded and overworked, died on the route. Dead Horse Gulch was aptly named.

Both Dyea and Skagway vied for the title of Gateway to the Klondike, but Skagway won because of the White Pass and Yukon Railroad. As The Bride will attest, a train ride is easier on a sprained ankle.

Hear the Train A-comin’

It was called “the railway built of gold,” and the narrow gauge railway certainly was an engineering marvel. Construction began on May 28, 1898, and thousands of men braved brutal conditions, including temperatures as low as 60 below, to complete a track that would climb nearly 3,000 feet in 20 miles, with hairpin turns, steep grades, two tunnels and plenty of bridges and trestles. On July 29, 1900, the railroad reached Carcross, 110 miles away, in the Yukon.

Since 1988, the train has operated for tourists, carrying passengers from Skagway to White Pass Summit in Bennett, British Columbia. The trip takes you past Gold Rush Cemetery, Inspiration Point and several reminders of the hardships on the trail such as Black Cross Rock, where two railroad workers were buried under a 100-ton chunk of granite on August 3, 1898.

At White Pass, Canadian Mounties allowed only stampeders with one ton of supplies (enough, in theory, to last a year) to proceed. International borders being what they are today, tourists aren’t allowed to disembark the train in British Columbia, so they take snapshots before the train returns to Skagway.

Cruise ships have landed at Skagway, and thus begins another adventure: Trying to escape tourists, which is hard to do in July. The Bride gamely takes advantage of her newly purchased walking stick and limps to our rental car, and we take off on Highway 2, following a newer version of the Klondike Trail.

O, Canada!

It was approximately 550 miles from Skagway to Dawson, across Lakes Bennett and Lindemann, and through some spectacular, if formidable, country. With its walls of basalt, Miles Canyon looks treacherous from above. I can hardly imagine how it looked to stampeders facing the current in their handmade boats. Even if they survived the canyon’s whirlpool, they still had to face Squaw Rapids and White Horse Rapids, and other dangers up the trail.

I’m more concerned about surviving tour buses. Every time we stop, we have a few minutes to ourselves before the roar of evil diesel engines portends tons of modern stampeders. Just up the road at Whitehorse, however, I don’t mind tourists so much.

We’re at the S.S. Klondike National Historic Site, taking the tour with another American family and some Canadians. The Americans are moving from Alabama to Fairbanks. The teenage daughter looks particularly bitter (from hearing one too many Robert Service poems, perhaps?).

The sternwheeler S.S. Klondike II came along far too late for the gold rush. Launched in 1937, she made her last run up the Yukon River in 1955 before Parks Canada restored her to her 1937-40 looks. Yet the park’s a great introduction to life on steamboats, and the upper Yukon became the major riverboat route for the stampeders of ’98.

From Whitehorse, the Klondike trail heads on north, ending, of course, at Dawson. The boomtown was everything Skagway wasn’t, thanks to the no-nonsense rule of Mounties.

Dawson City—End of the Trail

Dawson and vicinity pay high tribute to the gold rush era—visitors still pan for gold at Claim No. 6 or get panning lessons at Claim No. 33—but Dawson also honors the literary world.

Johnny Horton aside (and he was singing about the Nome rush, a few years later), how much would we remember about the Klondike if not for Jack London? For that matter, historians and history buffs owe a great deal of thanks to Pierre Berton and his seminal 1958 work The Klondike Fever.

Jack London came to the Yukon in September 1897 only to find his fortune later in fiction (Call of the Wild; White Fang). He lived on the North Fork of Henderson Creek, where trappers happened upon an abandoned cabin in 1936 and discovered London’s signature on the back wall. The Jack London Cabin was re-created in Dawson from the original logs of that cabin—another replica was built in Oakland, California, London’s hometown—and today, the cabin sits next to the Jack London Museum operated by the Klondike Visitors Association.

Pierre Berton grew up in Dawson, leaving at age 12, and the Pierre Berton House, operated by the Berton House Society, houses a Writer-in-Residence Program that gives Canadian writers the chance to work in a “remote northern” location. Well, Dawson’s certainly that.

Oh, yeah, you’ll hear a lot of Robert Service poetry in this town, too. Be careful. This is dangerous country.

Visit “Website Extras” at twmag.com to read Johnny Boggs’ take on Robert Service.

Whatever you do, don’t get Johnny D. Boggs started on his fishing adventures in Alaska unless you really like to hear about fighting 30-, 28- and 26-pound salmon (The Bride, bum ankle and all, landed a 28-pounder!).

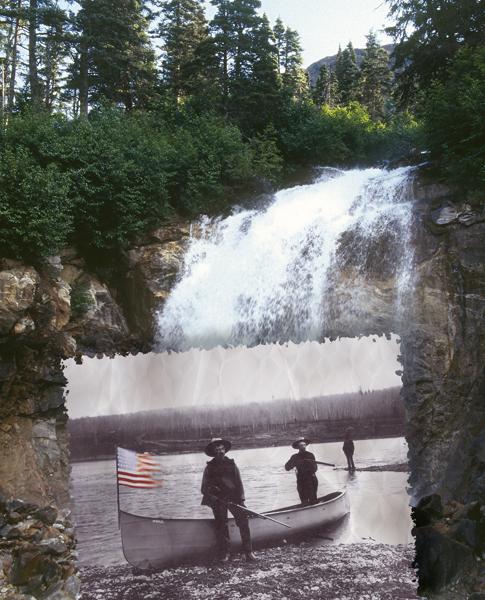

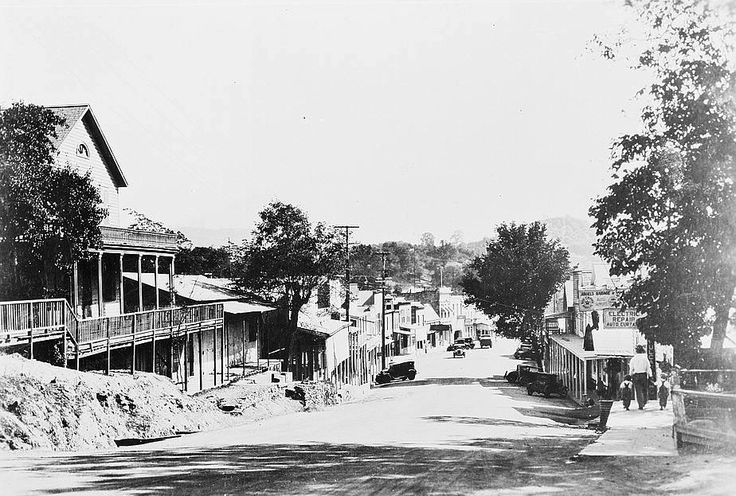

Photo Gallery

– All images by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted; Center photo: True West Archives –