Johnny Cash is playing on the ol’ stereo. Okay, so that’s not news—his music is practically always playing on the stereo.

Johnny Cash is playing on the ol’ stereo. Okay, so that’s not news—his music is practically always playing on the stereo.

But this is appropriate because I’m listening to Cash’s 1964 masterpiece, Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. Crank it up.

Now I will tell you, buster,

That I ain’t a fan of Custer’s,

And the general,

He don’t ride well anymore.

Okay, so I always crank it up. Like most songs on Bitter Tears, “Custer” was written by Peter LaFarge, the Nargaset Indian adopted by Pulitzer Prize winner Oliver LaFarge. Those songs did a lot for the Indian movement during the 1960s (LaFarge also wrote Cash’s hit “The Ballad of Ira Hayes”) before LaFarge died of—take your pick—a stroke, drug overdose or suicide in 1965 at age 33.

LaFarge helped found the political activist group Federation for American Indian Rights, and I’m thinking he would be proud of what has happened at Little Bighorn National Battlefield Monument just off I-90 in southern Montana.

Keep in mind that the name was once “Custer National Battlefield” from 1946-91. Often overlooked were the Sioux, Cheyenne Arapaho and Crow until June 25, 2003, when a crowd gathered around the new Indian Memorial, not far from Custer’s Last Stand Hill. The circular monument honors both the Indian defenders as well as the scouts who worked for the Seventh Cavalry during the famous 1876 battle. Lakota actor and activist Russell Means showed up for the dedication ceremony and to get his name and photo in the papers. Okay, so that’s not news, either.

Maybe LaFarge wouldn’t be so pleased with the memorial. Heck, maybe Means should come back to drum up some more publicity for native causes. It’s a beautiful summer morning, but there are only two people hanging around the Indian Memorial. One of them happens to have Johnny Cash in his car stereo. The other is a park ranger. Across the road, busloads of tourists are strolling around Last Stand Hill, snapping pictures of the headstones of soldiers and the big monument that always reminds me of that great Twilight Zone episode from Season Five (“The Seventh is Made Up of Phantoms”).

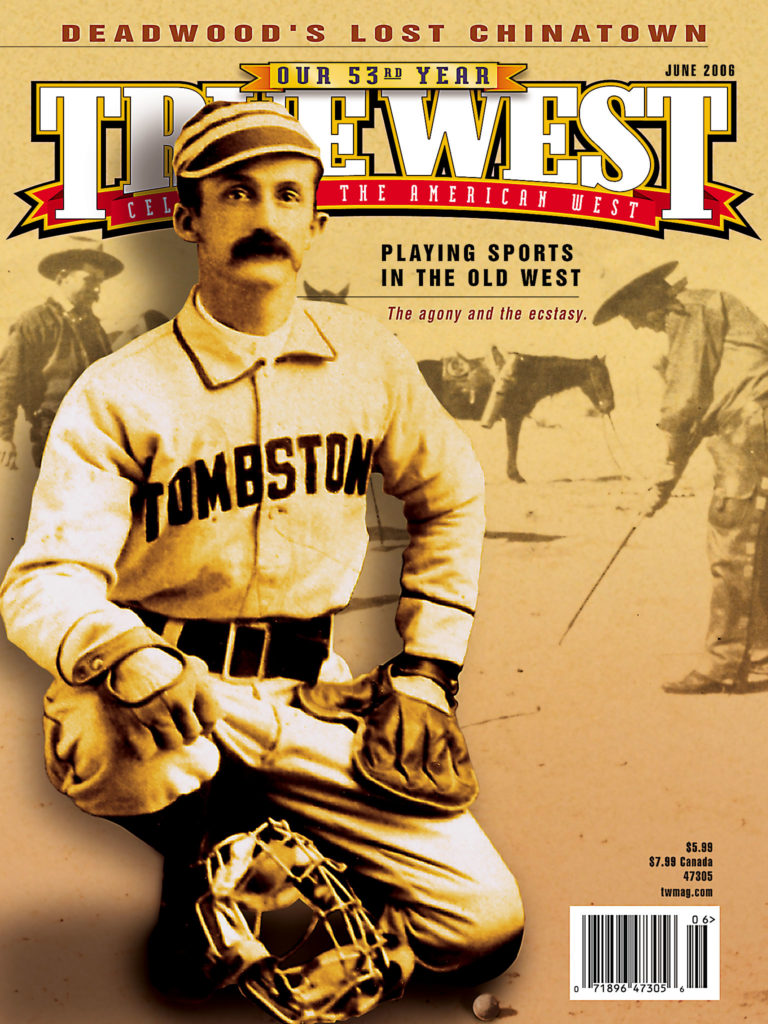

Time to go. I zip down I-90 and cross the border into Wyoming. Only 70 miles from the Little Bighorn, Sheridan is cowboy country. Buffalo Bill Cody hung his hat at the Sheridan Inn. Sheridan is the land of the Bozeman Trail. It’s the home of the King’s Museum, just behind King’s Saddlery, with its great collection of Western art, artifacts and some 500 saddles. Sheridan is also home to the Trail End State Historic Site, the 1913 mansion that was once home to John B. Kendrick, a poor Texas cowboy who pulled himself up by the bootstraps to become a successful Wyoming rancher and U.S. senator.

This is also Peter LaFarge country. That’s because before making a name for himself as a protesting Indian folk singer/songwriter, LaFarge worked as a cowboy and rodeo rider.

Cash is playing on the ol’ stereo again. Okay, so he’s practically always blasting on the stereo. But this is appropriate because now I’m listening to Cash’s 1965 masterpiece, Johnny Cash Sings the Ballads of the True West. Crank it up.

Stampede!

They’re comin’ up the draw.

Stampede!

Three thousand head or more.

Here they come a-smokin’ fire,

Boys, you better earn your hire.

Stampede!

And hell to score.

In this country, on this road trip, there’s a LaFarge song for every stop.

Road warrior Johnny D. Boggs recommends the Historic Sheridan Inn in Sheridan.