Then the rattling of the coach, the clatter of our six horses’ hoofs, and the driver’s crisp commands, awoke to a louder and stronger emphasis; and we went sweeping down on the station at our smartest speed.”

Then the rattling of the coach, the clatter of our six horses’ hoofs, and the driver’s crisp commands, awoke to a louder and stronger emphasis; and we went sweeping down on the station at our smartest speed.”

What better way to travel a Renegade Road than with Mark Twain, even if he went roughing it on the central route from Missouri to California via Denver and Salt Lake City, while my assignment covers John Butterfield’s original path, south through Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California. Even if I have no plans on roughing anything, especially me.

The Overland Mail Company came into existence in 1857 when Congress authorized mail service to the Pacific Coast: twice-a-week service with delivery taking no more than 25 days. (If only my bosses could get my check to me in no more than 25 days.)

Traveling the Overland Mail Company route could begin in St. Louis (via railroad to Tipton, Missouri) or Memphis, Tennessee. St. Louis has the Cardinals, the Gateway Arch, a great zoo and god-awful humidity. Memphis has FedEx (since we’re talking about the mail), barbecue, Blues, Graceland and god-awful humidity. By default then, we’ll begin in Fort Smith, Arkansas, where the St. Louis/Tipton and Memphis routes converged.

Fort Smith blends Old West history with Old South charm (except for all those obnoxious Razorback fans). It has Fort Smith National Historic Site, with Hanging Judge Isaac Parker’s courtroom and 1886 gallows restored for history buffs. There’s no Overland Mail museum, but the city does have a trolley museum and carriage tours—and god-awful humidity, though not quite as god-awful as you’d find in St. Louis or Memphis.

Stagecoach Jam

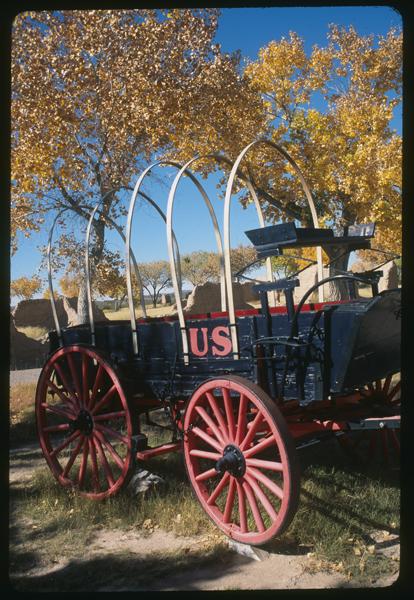

Stations were built at about 20-mile intervals, and the company had a year to get things ready for the first run. On September 15, 1858, the first Overland journey began, 2,800 miles to San Francisco, California, with coaches running day and night.

With a $600,000 contract, Butterfield and his associates purchased 250 stagecoaches and 1,800 horses and mules, and hired 1,200 men as superintendents, guards, blacksmiths, clerks and drivers.

The drivers had to cover about 60 miles (armed guards, 120 miles). For $200, passengers could travel from St. Louis to San Francisco (shorter routes were about 15 cents a mile). Those Concord coaches could get crowded, too. As a San Antonio Herald reporter noted in 1858, “To make excellent jam; squeeze six or eight women, now-a-days, into a common stage-coach.”

Roughin’ It in Oklahoma

The route covered 197 miles in Oklahoma, from Walker’s Station at the old Choctaw Agency to Colbert’s Ferry on the Red River. About all you’ll find are historical markers as you travel the trail. Geary’s Station lies under Atoka Reservoir near Springtown, but most stations (Holloway’s, Pusley’s, Blackburn’s, Waddell’s, etc.) are remembered by markers; you’ll do some roughin’ it traveling to many of the markers the major highways bypassed.

Yet, there are some interesting sites to visit along the way: Robber’s Cave State Park near Red Oak, a former hideout of Jesse James and home to Holloway’s Station near the “Narrows”; Lutie, home to Riddle’s Station and the Old Riddle Cemetery; Boggy Depot State Park near Boggy Depot; and Fort Washita, not far from Durant, an 1842 fort built to protect the Five Civilized Tribes from Plains Indians.

From Colbert, the trail crossed the Red River into Texas. Originally, the stages ran to Sherman, west to Gainesville and on toward Jacksboro and Newcastle, but the route eventually dipped from Sherman south to Denton, and then over to Decatur and Jacksboro (check out Fort Richardson, now a state park) and Newcastle.

The Overland Trail covered a lot of forts in Texas. One of my favorites, and among the most overlooked old Texas forts, is Phantom Hill near Abilene. Cool name. Cool ruins. Cool cactus. Not as much god-awful humidity.

Not the Prettiest Town, But …

In fact, Abilene is one of Texas’ most underrated burgs. The city’s top-notch custom bootmaker (Alan Bell) and plenty of attractions should please adult and children visitors.

The city didn’t come along until the Texas and Pacific Railroad came through in 1881—too late for the Overland, but Frontier Texas!, a multi-million dollar history/entertainment facility downtown, lets visitors get up close with the region’s history between 1780-1880.

Just down the pike, nearby Buffalo Gap Historic Village offers re-creations of West Texas of 1883, 1905 and 1925, complete with 15 historic structures, including log cabins, a schoolhouse, railroad depot and the 1879 Taylor County Courthouse.

Take U.S. 277 past Fort Chadbourne near Bronte and into the bustling Texas town of San Angelo. Then ride along U.S. 67 and 385 toward Girvin. Historical markers (at a roadside park on 67/385 south of Crane and another on F.M. 11 north of Girvin) note the importance of Horsehead Crossing, the famous ford of the Pecos River and a crackerjack Elmer Kelton novel (which has nothing to do with the Overland Mail Trail, but we like to give Elmer free press).

Choices … choices …

Horsehead Crossing is important because here is where the trail split again. The original route turned north, to Emigrant Crossing, the Pinery, Guadalupe Pass, Hueco Tanks and into El Paso. This is a great trip. Spend time at Guadalupe Mountains National Park and visit the ruins of the Pinery Station, and hike up McKittrick Canyon or Devil’s Hallway. Then swing down past the Salt Flats with another good hiking venture at Hueco Tanks State Historic Park before entering El Paso.

The later route continued southwest toward Fort Stockton, which was established in 1859 to protect the stagecoach route, and then on through some of Texas’ most spectacular country: through Fort Davis, Van Horn’s Wells, San Elizario and into El Paso. This is a great trip, too. You should definitely hang out in Fort Davis and visit the Fort Davis National Historic Site and the Overland Trail Museum (one of the few museums along the trail actually named after that trail!). Then swing north to Van Horn before picking up I-10 and heading west into El Paso.

Land of Enchantment

From El Paso, the trail entered New Mexico Territory. Las Cruces/Mesilla is always a fun stop, if only for food at La Posta de Mesilla. Built in the 1840s, the compound is said to have become an Overland station. Later, it was home to the Corn Exchange Hotel. Forget Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, Albert Fountain, John Butterfield and the other historical figures who passed through here. The greatest of them all had to be Katy Griggs Camunez, who started La Posta de Mesilla Restaurant in 1939. (Can you say Banquette Elegante and a cranberry margarita?)

I like New Mexico’s brief trail because these stagecoach stations had the coolest names. Cooke’s Spring. Soldier’s Farewell. Steins isn’t so bad, either. It’s a ghost town off I-10 near the Arizona border, although the town didn’t come around till the Southern Pacific came in 1880. Shakespeare, near Lordsburg, is also a favorite among ghost-town buffs.

In Arizona, the trail cut through San Simon and Apache Pass, so plan on visiting Fort Bowie National Historic Site. A hiking trail takes visitors past the station ruins on the way to the weathered ruins of the old fort, originally established in 1862 and moved to a nearby hill six years later.

Tucson Pampering

For convenience (and gas), head back to I-10 from Fort Bowie via Willcox and continue west to Tucson. The Westward Look Resort in Tucson was not a station, and that’s too bad. We still might be riding stages to California had John Butterfield hired Jamie West as his executive chef. Forget hardtack, jerky, pork, beans and coffee (not to mention sharing coffee cups). Forget the San Francisco Bulletin journalist who wrote, “there is no place between Los Angeles and El Paso where a decent meal can be procured” or the Frenchman who called one meal along the trail “distressingly bad.” Forget your diet (especially after La Posta, too). The Westward Look is a great place to recharge your batteries because it’s still a long, long way to the end of the line, and southern Arizona can tax even the heartiest driver.

If you need to burn off those calories, swing into Picacho Peak State Park, site of the most Western of all Civil War battles, not that it was much of a battle. Then it’s on west along Interstates 10 and 8 to Yuma, where you can thank God there is no god-awful humidity. “It’s a dry heat,” the skeleton says on a popular T-shirt.

Yuma is desolate, but the Yuma Territorial Prison State Historic Park is a cool (figuratively, of course) stop. A ranger keeps saying he’ll tell me the true story of the pen. One of these days, I’m going to take him up on that offer—maybe during the winter.

From Yuma, the trail crossed the Colorado River into California. If you feel like wimping out, you can take I-8 to San Diego (great town) then shoot up I-5 to L.A. and the 101 to San Jose and San Francisco. That’s not exactly the Overland Trail, but it is convenient, or as convenient as California traffic ever gets.

I mention this alternative because the Overland Trail didn’t make things easy in California, even if Butterfield did follow established roads: Indian Wells, San Felipe, Warner’s, El Monte, Widow Smith’s, Firebaugh’s Ferry, Pacheco Pass. And you thought Soldier’s Farewell was hard to find?

California Dreaming

Exit the interstate west of El Centro at Ocotillo—the road less traveled these days winds through some mighty interesting country. You’ll head through Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. Along the way, there’s the reconstructed Vallecito Station, a home station during the Overland days, at a county park near Agua Caliente Springs.

Near the intersection of Highway 78, you’ll find the San Felipe Valley station. Julian, San Diego County’s one and only Gold Rush town, is a worthy rest stop before pushing on north to Oak Grove. So is the historic Warner Springs Ranch in Warner Springs, situated on the old Overland road. In Oak Grove, the old Oak Grove station still stands on Highway 79, although it’s a renovated store these days.

Eventually, though, one has to fight congestion and headaches. John Butterfield would never have met his deadline had his drivers been forced to deal with Orange County/L.A. County traffic. But if you get through to L.A., make sure you stop at the Autry National Center. The exhibits are always first-rate.

From L.A., we push on north, through Merle Haggard/Buck Owens Country: Bakersfield, Tulare and Visalia, where the Tulare County Historical Society preserves regional history at the Museum of Tulare County and with historical markers throughout the area, several of those designating the stagecoach stations. Another good stop is up the road in Fresno, where the Fresno Historical Society operates the Kearney Mansion Museum. All right, M. Theo Kearney had nothing to do with the Overland Trail. He made his fortune in raisins.

I like raisins. If you prefer barley, there’s the Butterfield Downtown Brewery, where you can claim to be researching Butterfield’s route.

Winding Down

After a few beers and a good nap, our focus must return. The road is almost trailing to an end, but one important stop can be found at Pacheco State Park, 24 miles west of Los Banos. The last remaining portion of the El Rancho San Luis Gonzaga land grant, this 6,890-acre preserve (donated in 1992) includes part of the Overland route. A line shack dating to the days of Monterey County cattle king Henry Miller can be found on the grounds.

Alas, you’ll have to fight more traffic in San Jose and, finally, the trail’s end in San Francisco. Before calling it quits, make sure you stop at the Wells Fargo History Museum and the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society.

Although the first run made the journey successfully, the original Overland route was doomed. Butterfield’s company had spent more than $1 million before the first stagecoach left, and critics blasted the trail’s oxbow course, arguing for a more central, direct line. The outbreak of the Civil War would force the change and abandon the southern route for the central trail, but even that would be short-lived. With completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the Overland Mail Company had outlived its usefulness.

But what a legacy it left.

As Mark Twain once wrote, “It was fascinating—that old Overland stagecoaching.”

Photo Gallery

– Above: True West Archives –

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –