If Vera McGinnis’ love story were a Country Western song, it would go something like this: “He dragged her heart around that ring, that handsome cowboy dark and lean; but settling down was not his thing, by the time she knew, she was a Rodeo Queen.”

If Vera McGinnis’ love story were a Country Western song, it would go something like this: “He dragged her heart around that ring, that handsome cowboy dark and lean; but settling down was not his thing, by the time she knew, she was a Rodeo Queen.”

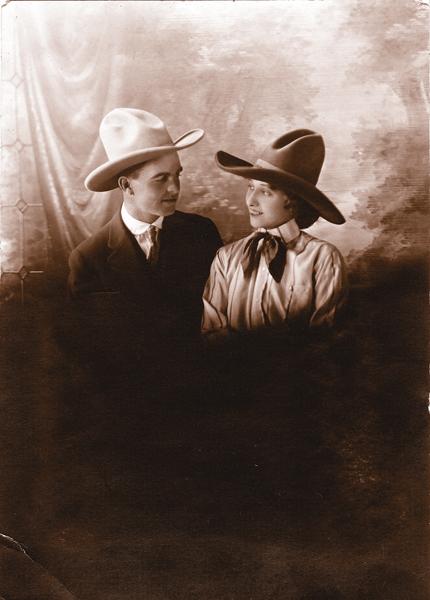

Vera’s “undoing,” as she’d later joke, began with a crush on one handsome cowboy and ended with marriage to another.

The first heartthrob was Art Acord, who showed up in Utah for Salt Lake City’s 4th of July Frontier Day Celebration in 1913. He was a Western picture and rodeo star she had met in Hollywood, and she always liked the “big blond Don Juan.”

Vera was working in Salt Lake as a stenographer, her first real job. She claimed to be 18 (but really was 21), was pretty as a picture and was thrilled at Art’s attention, not knowing he was really playing big brother.

Art was most excited because a “real hand” named Earl Simpson was coming to compete in the rodeo. “Art seemed altogether too interested in what I was going to think of Earl,” she’d write years later in her autobiography, Rodeo Road:?My Life as a Pioneer Cowgirl.

And then she got her first glimpse of the man who’d drag her heart around. Earl Simpson had sparkling black eyes, straight black hair, a cleft chin and was “a bit more reserved without a horse under him.” Vera was instantly hooked and besides, she fell in love with his horse. Shy Earl used nightly rides on Black Bud as a courting help, but Vera was too young and naive to the ways of cowboys to understand. She wanted a man to tell her how he felt and Earl wasn’t a tellin’ type.

She complained to Art, “He doesn’t know I’m here.” Art laughed and told her, “I’ve a hunch Simpson’s got some Indian blood way back and it crops out in his courtin’. Try ridin’ along as silent as he is. He’ll thaw out.”

Vera bet on it: given the chance to jump into Earl’s world, she leapt.

Toward the end of the rodeo run in Salt Lake, Vera overheard a promoter wishing he had another girl rider for a relay race, and she instantly volunteered. She’d ridden bareback and sidesaddle as a child but hadn’t been on a horse in years and wasn’t from the ranching life as were most girls in the rodeo. But that didn’t dim her enthusiasm, although she was about the only one excited.

Art thought the idea was absurd. “I’m thinking she’d make a better singer than she would a cowgal, with them canary legs,” he said. But the rodeo promoter took Vera up on her offer, and although she had no idea how to ride a relay race, she got some help and competed the next day.

She wore blue ribbons in her hair and a khaki divided skirt with a plain white shirtwaist over her Bon Ton corset. If Earl noticed, he didn’t say a thing.

But then, Earl was busy teaching this city girl how to saddle a horse. She found the saddle far heavier than she’d expected, but she soon got the hang of it and earned a smile from Earl. “An electric shock jumped at me that had nothing to do with saddling a horse,” she’d remember.

She ran her first race and came in third.

The next day she quit her secretary’s job and packed her few belongings to join the rodeo circuit that was Earl’s life.

Although they were together every day now, Vera found they had different ideas. Earl saw marriage as “a work-harness slung across his withers.” So at the end of the season—going from Canada to the West Coast—a disappointed Vera went home to Mama in Missouri.

Six weeks later—bored, lonesome for Earl, unsure about her future—Vera got a telegram offering her $50 to ride in a Wild West Show in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was a “step down” from rodeoing, but she needed the experience and the money.

Then a note came from Earl. Nobody else would have called it a love letter, but that’s how Vera read the one page that arrived at the end of the Tulsa show. Earl said he was living in Los Angeles with his partner’s family and they all wanted her to “come join the family.” She took off for the West Coast and in the spring of 1914, married Earl.

They honeymooned on the rodeo circuit: Bakersfield and Stockton in California, Klamath Falls in Oregon.

After the season, she and Earl went to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, looking for a small ranch where they could settle down. Earl dreamed of raising horses, Vera dreamed of raising children. But “Old Dame Rodeo” kept calling them back each season. Finally, Vera pushed Earl to search seriously for a homesite. He found a piece of land near Jackson Hole he thought would be perfect for his barn. Vera wondered where he saw the house, and he vaguely answered “up there somewhars.”

His indifference infuriated her, and she yelled at him, “I want a home of our own, somewhere decent to raise our family.”

As she recalls in her autobiography: “He wheeled on me like I’d struck him. ‘You might as well know now, there ain’t goin’ to be no family.’ And without waiting for my reaction, he walked off down the slope. My anger drained as I sank to the ground in dismay.”

They never went back to Jackson Hole.

A different road

She and Earl wintered in Phoenix in 1916, living in make-shift places and finding funds so low “the bacon was down to hanging on the highest beam.”

Earl wanted to stay in Arizona and race a string of horses he’d put together. She saw that as “crumbs” and left him to follow the circuit by herself. She returned that fall “so thin I had to stand in one spot twice to make a good shadow.” But the rest she needed had to wait because “Earl didn’t hesitate to hang the work collar on me.”

Vera was helping support the family by winning races and exercising horses for paying customers—in between doing all the cooking, cleaning and laundry for Earl and his father. It wasn’t a happy situation; wasn’t a happy home. When Uncle Sam called Earl for WWI, he went off to the army and she moved to Los Angeles, California, with her only possessions—a horse named Casandra and a trunk of homemade costumes.

She supported herself wrangling and working as a stunt double in the movies. “But, I had evidently lost my husband,” she’d recall. “He wrote that the army had turned him down and that was the end of his communications. I watched the mail with a heavy heart as the months went by, but, as he’d so often told me, all I could do was ‘make the best of it.’ And I tried.”

Earl did come back, and they tried parallel lives: her rodeoing each season; him working with actor Tom Mix. They spent their winters in “Mixville,” the actor’s motion picture headquarters.

“My life had ceased to revolve around him,” she’d say. “It didn’t occur to me to give up my career to save my marriage.”

They divorced in 1921, saying they agreed to “preserve our friendship.” But if she ever saw Earl Simpson again in her lifetime, she didn’t bother to mention it when she wrote her life story.

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy of Vera’s grandniece Phyllis Gendreau –