The late November dawn broke cold and foggy.

The late November dawn broke cold and foggy.

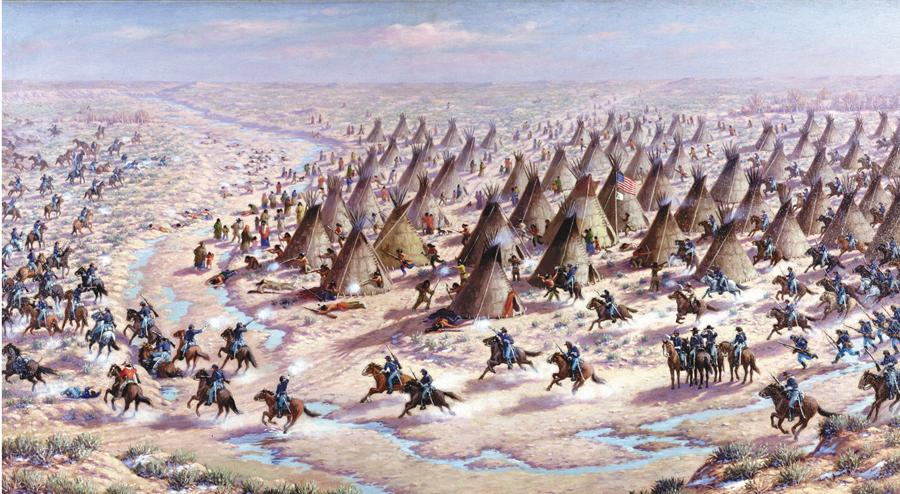

Below the barren Southeastern Colorado plain, some 600 Arapaho and Cheyenne Indians were camped in a ravine alongside a dry streambed called Big Sandy Creek. Six hours later, a quarter of them—mostly women and children—were dead at the hands of a Colorado volunteer militia. In time, the name Sand Creek would become synonymous with massacre.

The 1864 massacre at Sand Creek, more than any other Indian conflict at that time, set the stage for the bloody battles yet to come on the American Plains. Among Indians, it stands as a decisive symbol of white-man betrayal, and among the citizens of Colorado, as the worst tragedy in the state’s history.

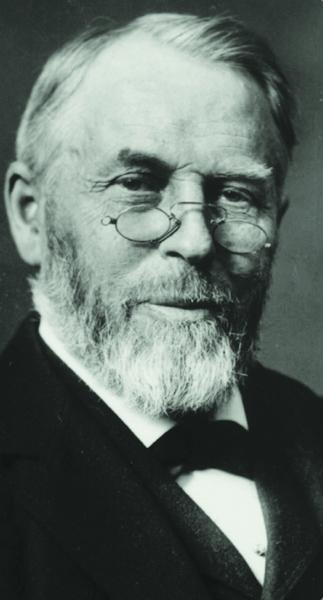

Earlier that year, roving bands of young Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors had raided Eastern Colorado and Western Kansas, causing alarm among the white settlers. Finally, Territorial Gov. John Evans called for a militia to end the Indian problem. The influential press, led by William N. Byers of The Rocky Mountain News, called for the “immediate extinction of the Indians.”

“The most revolting, shocking cases of assassination, arson, murder and manslaughter that have crimsoned the pages of time have been done by the Indians, in former days and recently—nevertheless we are opposed to anything which looks like a treaty of peace with the Indians…. The season is near at hand when they can be chastised and it should be done with no gentle hand,” wrote Byers in The Rocky Mountain News on September 28, 1864, clearly stating the views of many citizens of the Colorado Territory.

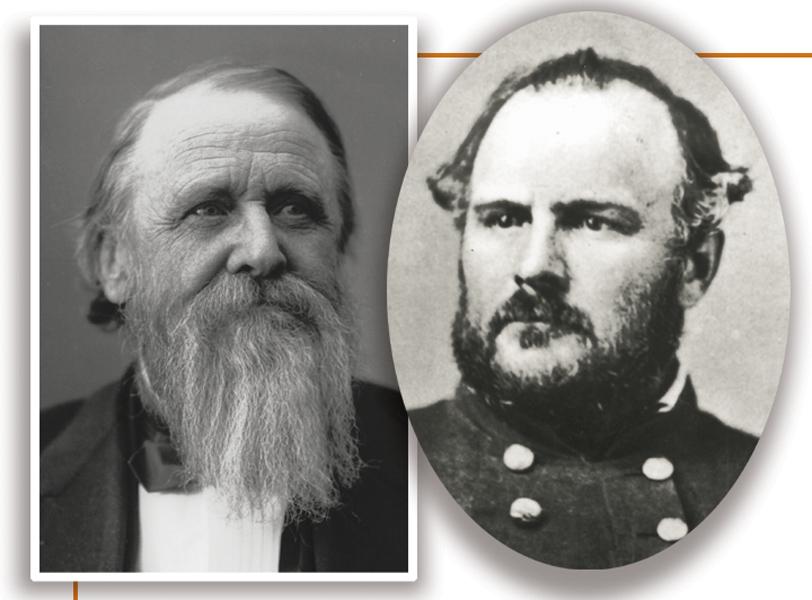

Territorial politics were reaching an explosive level. The powers at large, primarily in Denver, had lobbied Washington a second time for admission to the Union. The stakes were high and the obstacles were numerous. Foremost on the minds of the political hopefuls, particularly Gov. Evans and Col. John M. Chivington, were the recent Indian uprisings. Now, with the support of the influential newspaper editor, the course was clear: eradicate the “Indian problem.”

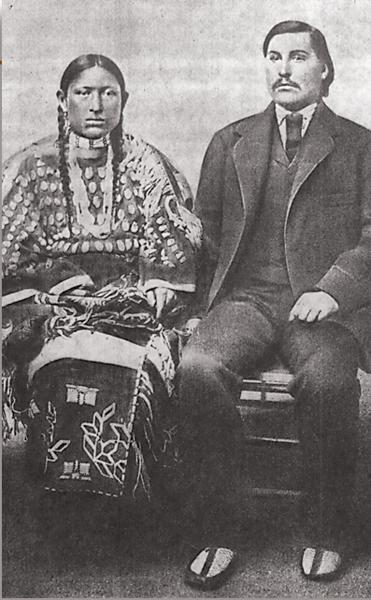

Into this escalating war between the white soldiers and the Indians came the mixed-blood George Bent, who rode with the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers that bloody fall. Torn between the volatile worlds of the white man and the Indian, Bent was the son of fur trader William Bent and his Cheyenne wife, Owl Woman. George was born in 1843 at Bent’s “Old” Fort, the famous trading post his father had built in Southern Colorado along the Arkansas River. His maternal grandfather was Cheyenne Chief Gray Thunder, the Keeper of the Sacred Arrows. At the age of 10, George and his siblings were sent to St. Louis, Missouri, for their education, where they lived with Albert Boone, grandson of the famous frontiersman. In 1861, George enlisted in the Confederate Army, participating in the battles at Wilson’s Creek and Pea Ridge. Taken as a prisoner after the siege of Corinth, he was eventually released because of pressure from his father’s influential friends. Returning to Southern Colorado and his home at Bent’s “New” Fort, 22-year-old George soon found himself in the middle of the oncoming war between the two cultures of his life.

William Bent, the first Indian agent in the region, as well as a friend and supporter of his wife’s Cheyenne tribe, knew that war was coming. No longer able to reason with Gov. Evans or the soldiers at nearby Fort Lyon, William sent his son to his mother’s tribe. George soon learned of the atrocities perpetrated against the Cheyenne by various companies of soldiers, and he began riding with the Dog Soldiers in retaliation.

Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle, widely respected as a fierce adversary of the Pawnee and Kiowa, believed in peace with the white man. In 1861, he had signed a treaty at Fort Wise, promising to remain in the vicinity of the Arkansas River and not to interfere with emigrants along the Smoky Hill Trail, thereby clearing the way for thousands during the Pike’s Peak gold rush.

The Cheyennes soon realized that the dry lands near the Arkansas River held little wildlife and that the white settlers had removed much of the area’s timber. The young Cheyenne warriors, including George Bent, refused to obey the Treaty of Fort Wise and launched raids among the whites.

When the Nathan Hungate family was found murdered just south of Denver, their scalped and mutilated bodies were brought to Denver and displayed to the public. Mass hysteria gripped the town. (The Cheyenne were later found innocent of the murders.)

Governor Evans issued a general proclamation dispatched to the Indian camps by messengers, ordering all peaceful Indians to assemble at Fort Lyon. Those Indians who did not comply would be killed. The order authorized the citizens of Colorado Territory to “Go in pursuit of all hostile Indians on the plains … kill and destroy, as enemies of the country, wherever the Indians may be found.”

Evans also wired an urgent plea to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, requesting authorization for military troops. “Extensive Indian murders, the Indian war begun in earnest,” wrote Evans in his wire.

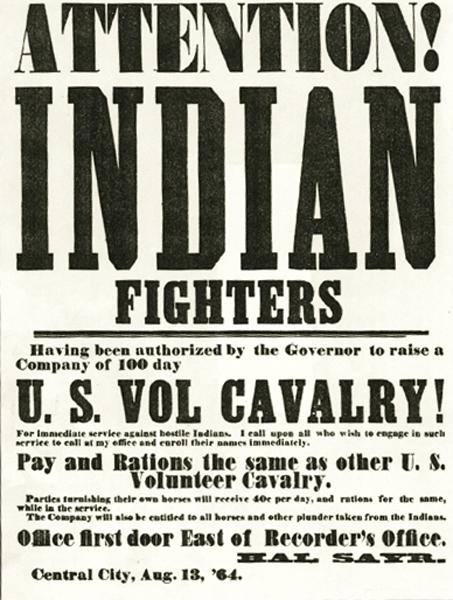

Washington, D.C. gave Evans the authority to enlist citizens for a regiment not to exceed 100 days. In less than a month’s time, the Third Regiment of Colorado Volunteers was assembled under the command of Chivington, a local Civil War hero, who had earned praise for his performance at Glorieta Pass.

While Evans stayed busy in Denver recruiting soldiers, Maj. Edward Wynkoop of Fort Lyon met with Black Kettle, who came to the fort in an effort of peace. After much talk, Wynkoop told the chief to bring his people, along with the Arapaho tribes, to the fort for peace negotiations. When Evans heard of the proposed peace talks, he was enraged. Wynkoop later testified that Evans said “it would be supposed at Washington that he had misrepresented matters in regard to the Indian difficulties in Colorado, and he had put the government to a useless expense in raising the regiment; that they had been raised to kill Indians and they must kill Indians.” But since Wynkoop had made a promise to the Indians, the governor was forced to meet with them.

“War has begun, and the power to make a treaty has passed,” he told the Indian delegation. Chivington ended the peace talks by informing Wynkoop that the Indians “could go to him when they were ready.”

Returning to Fort Lyon, Maj. Wynkoop acknowledged the peace tribes of Chiefs Black Kettle, White Antelope, Little Raven and Left Hand, and he told them to camp at Sand Creek, 40 miles north of the fort, as he didn’t have enough rations to feed all their people. He also supplied them with firearms to hunt game. Shortly thereafter, Wynkoop was suddenly relieved of his command and replaced by the self-centered, pompous Maj. Scott Anthony.

Evans and Chivington now proceeded with their plan. The new regiment was nearing the end of its 100-day service. Evans and Chivington needed a military victory against the Indians for the citizens of Colorado and their own political agenda. In their minds, both causes were the same; the victory would lead to political triumph.

At camp on Bijou Creek, Chivington rallied his men to the task before them. In a venomous speech, frothed with Indian hatred, Chivington ended by spewing: “take no prisoners. Nits make Lice.” Leaving camp, the troops marched doggedly for 200 miles in a severe snowstorm, at times two feet deep.

On the early morning of November 29, 1864, Chivington’s troops, together with the Colorado First Regiment—Maj. Anthony’s troops from Fort Lyon—charged into Black Kettle’s camp. Supporting the armed troops were four 12-lb. howitzers.

When the first shots were fired by the troops, fewer than 100 Indians ran up the creek bed to take cover in the rifle pits. The chiefs and the few warriors in camp defended their people as best they could.

As a military operation, the battle was a horrible bungle. Military command was lost early in the day, as soldiers were caught in their own cross fire. The surprised and ill-armed Indians held their own and kept the soldiers at bay for some time. Meanwhile, nearly 500 Indians, including Black Kettle, escaped across the prairie. Those who could not flee died on the spot.

White Antelope was among the first killed. Once the firing began, he left his lodge with arms extended, in the traditional sign of peace, and he was shot down in a single volley of fire.

Eyewitness testimony estimated the number killed to be just under 200, while Chivington boasted 600 “hostiles” were killed, including Chief Black Kettle. Two-thirds of the dead were women and children.

George Bent later recalled, “I looked toward the chief’s lodge and saw that Black Kettle had a large American flag tied to a lodge pole. The Indians were all running but they did not seem to know what to do. I got my weapons … and joined a group of middle-aged Cheyenne men. We made a stand, but troops came up the west side of the creek and opened hot fire … we ran up the creek with the cavalry following … I was struck in the hip by a bullet but managed to tumble into a hole. Finally they withdrew, killing all the wounded laying in the creek bed.”

As Black Kettle and his wife fled toward the prairie, she was shot. Afterwards, troopers put eight more bullets into her body. A bit later, Black Kettle returned for his wife, and seeing her alive, threw her over his shoulder and ran. By noon, or “when the sun was high in the sky,” recounted the Indians, the battle had ended.

Following the massacre, Chivington received a hero’s welcome in Denver. It took three years before a Congressional inquest denounced him and his actions.

In October 1867, George Bent served as a witness and official treaty interpreter at the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, where the Cheyenne and Arapaho agreed to allow railroads in the Platte and Smoky Hill Valleys, and to end all attacks against white settlers. In addition, the tribes agreed to exchange their land in the Colorado and Kansas Territories for a reservation in the Indian Territory, which was to be bounded by the 37th parallel and the Arkansas and Cimarron Rivers. Among the Cheyenne leaders to sign the treaty were Black Kettle, Bull Bear, Tall Bull and White Horse.

George Bent later commented: “This is the most important treaty ever signed by the Cheyennes, and it marked the beginning of the end of the Cheyenne as a free and independent warrior and hunter, and eventually changed his old range, from Saskatchewan to Mexico, to the narrow confines of a reservation in Oklahoma.”

Colorado author Linda R. Wommack’s latest book is Our Ladies of the Tenderloin: Colorado’s Legend and Lace, and she is currently working on a documentary film of the Sand Creek Massacre for Rocky Mountain PBS.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Denver Historical Society –

– Courtesy Colorado Historical Society –

– Courtesy Linda R. Wommack –

– All photos courtesy Denver Public Library, WHC unless otherwise noted –