Has Hollywood forgotten that the 1903 Western The Great Train Robbery jump-started the movie industry?

Has Hollywood forgotten that the 1903 Western The Great Train Robbery jump-started the movie industry?

When the self-financed Open Range was recently released, Director Kevin Costner said audiences will always be drawn to the genre because “the Western is about feelings of men, how people communicate with each other, about land.” Yet despite Open Range staying on the top-10 list for five weeks and turning a profit, some people in Hollywood aren’t too keen about the genre’s livelihood.

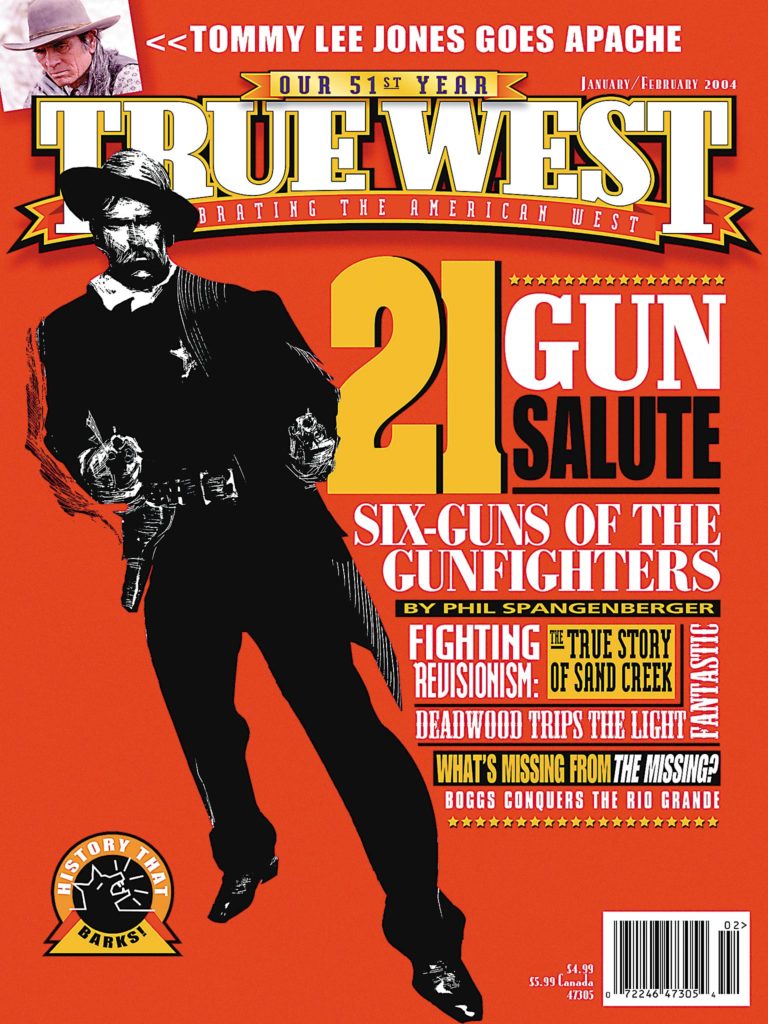

Due out on November 26, The Missing is “a story of healing and reconciliation that also has the twists and turns of a thriller,” says its Academy-award winning Director Ron Howard. “I wasn’t looking to merely exercise an old genre, but rather to tell a story that was relatable on a human level and exciting and suspenseful—but that still treated the period in an authentic way.”

What’s missing from Howard’s statement? One very telling word: Western.

So, is all quiet on the Western front as far as audiences are concerned? Not according to recent upsellers like Costner’s Open Range, hit telefilm Monte Walsh and USA series Peacemakers. Even Steven Spielberg is throwing his hat into the Western ring with a 12-hour epic on the American frontier due out in 2005. Fans still nominate John Wayne to the top-10 movie star list in the annual Harris poll, making him the only deceased actor to win (he ranked sixth in its most recent poll). And dare we forget that the 1990 Dances With Wolves and 1992 Unforgiven were best picture Oscar winners, clear signs that Westerns appeal to modern audiences.

As actor Sam Elliott says about the Western, “I don’t think it has ever fallen out of favor with the general public. It was Hollywood that abandoned it.”

The Missing: A suspenseful “Western” thriller

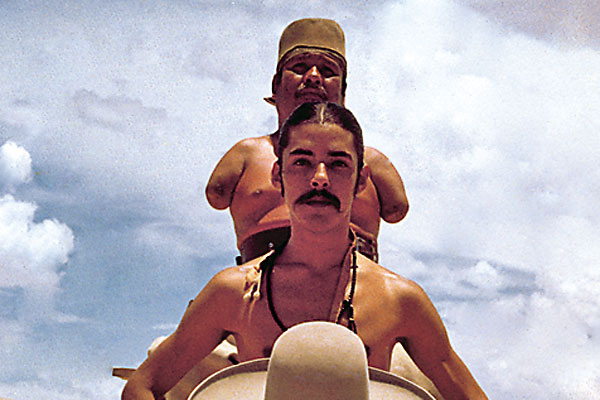

Howard’s The Missing is set in 1885. After 20 years living with the Apaches, Jones (Tommy Lee Jones) gets bitten by a rattlesnake—a bad omen.

“Reuniting with his family is one of many things he must do to save the life of his soul,” says actor Jones about his character. “So when he comes to take care of his family he’s motivated by survival. But anyone who works hard to take care of their family is, whether they know it or not, motivated by survival.”

When Jones returns to salvage his relationship with his daughter Maggie Gilkenson (Cate Blanchett), Maggie’s teenage daughter Lilly (Evan Rachel Wood) is kidnapped by Pesh-Chidin (Eric Schweig) and his gang of white renegades and Native American turncoats. The two estranged family members must rely on each other’s help, even as Maggie’s resentment for Jones threatens to undermine their rescue efforts.

“You never know if they’ll make it. They surprise you in different ways and you’re pulling for them to survive throughout the film in a way that keeps you constantly out of balance and on the edge of your seat,” says Producer Brian Grazer, who like Howard, publicizes the film more as a thriller than a Western.

Just as other Western directors have crafted their films to speak to modern audiences, Howard hired Salvatore Totino as his director of photography because “the scariest, most suspenseful films are the ones that put the audience in the mindset of the characters,” something Howard says Totino masterfully accomplished in Changing Lanes and Any Given Sunday.

“I wanted to approach the Western in a more unconventional and suspenseful way because it’s also a thriller,” Totino says. “The idea was that the style should underscore the emotions and the tension.”

In The Missing, Totino uses different color filters for each New Mexico location so that the various hues underscore the emotion of each sequence. For example, he uses a coral filter for the bloody shoot-out and rescue at Ghost Ranch, while the Zia Pueblo’s tension-filled scenes are overlaid with a blue hue.

Hollywood’s ambivalence toward the Western

Even though The Missing is undeniably a Western, Howard is not the first in Hollywood to shy away from the label.

The ups and downs of the Hollywood Western were discussed among three film historians and authors in a PBS special that aired in August 2003.

Although silent star William S. Hart was discouraged from doing Westerns because the market was saturated, he rejuvenated the genre, said R. Philip Loy, author of Westerns in American Culture, 1930 to 1955. When talking motion pictures began, Westerns died out again “because they are not filmed on soundstages; they’re filmed outdoors in what was then the undeveloped California landscape…. And you can’t get the microphones out there. So the assumption was that you can’t film a sound Western.”

But the Western did come back in the form of inexpensive “B” Westerns. In the 1930s, “the ‘B’ Western began to die out because gangster movies were much more exciting,” Loy said. “And then along comes the singing cowboy and Hopalong Cassidy” and the Western was popular again.

Costner certainly isn’t the first director to buck Hollywood bean counters and follow his dream to make a good Western. John Ford had trouble acquiring financing for his 1939 film Stagecoach. “The big studios didn’t want to finance the Westerns anymore,” said Holly George-Warren, author of Cowboy: How Hollywood Invented the Wild West. “And [Ford] was so interested in the story that he turned into the film that he went for it and, of course, it made the Western comeback huger than ever.”

So, was Henry Fonda right in the 1973 My Name is Nobody when he says that they were all a bunch of romantic fools who still believed that a good pistol and a quick showdown could solve everything? Is the Western label the kiss of death?

The answer is yes, says one film critic. “All the old Western expedients are frayed to a frazzle and audiences have become familiar with them to the point of contempt.”

But if this critic had been right, the Western would’ve bit the dust in 1911, when this review was written.

So don’t worry, Mr. Howard. Even though your secret is out, your film will be the better for it.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Eli Reed/Sony Pictures –