March 6, 1836

Did He Go Down Swinging or Surrendering?

Just after midnight, Gen. Santa Anna orders his 2,064 troops to move toward their assault positions. Select soldados (soldiers) stealthily sneak up on the Tejano sentries, who lie in dugouts positioned away from the Alamo, and slit the guards’ throats.

Just before sunrise (around 5 a.m.) a soldado from the second column yells out “Viva Santa Anna!” His comrades echo the cry. Furious that he has lost the element of surprise, Santa Anna orders his musicians to sound the attack. A rocket battery fires the signal to start the assault.

Four separate Mexican columns surge out of the darkness toward the shadowed walls of the Alamo. Awakened by the shouts, the Texans quickly man their cannons and commence a furious enfilade fire from the church and corral batteries, forcing the attackers coming in from the east to move north.

Musket and cannon fire pour from the walls of the Alamo, and three attacking columns stall at the north wall. The Texans are holding their own and laying down a deadly fire.

Momentum lost, Santa Anna commits his reserves. Grenidiers (grenediers)?and zapadores (sappers)?charge into the fight and finally succeed in breaching the Texan defense. At the same time, the cazzadores (light infantrymen) breach the Alamo’s southwest corner from the west side. The Texans fighting there are quickly overwhelmed and fall back, taking refuge in the adobe apartments, convent and church. Mexican troops pour into the compound unchecked, while others seize the abandoned batteries, turn them around and fire at the retreating Texans with their own cannons.

Hand-to-hand combat is fierce, and the fighting turns especially bloody as the Mexican troops go room to room, overwhelming each pocket of resistance and shooting and bayoneting everything that moves.

Some 60 defenders break out of the Alamo, heading east on Gonzales Road, but Santa Anna’s cavalry is waiting and cuts them down.

An hour after the initial attack, Davy Crockett stands alone, still proudly and tenaciously defending his diminished position (see map, p. 49). A frightful gash angles across his forehead. Holding the barrel of his shattered rifle in his right hand and a Bowie knife dripping with blood in his left, Crockett faces his attackers with the courage of a lion. Twenty dead or dying Mexicans lay beneath his buckskin-clad feet.

The man from Tennessee crouches, daring his attackers to take him. As they move in for the kill, Davy swings wildly with everything he has, until he finally falls, fighting with savage ferocity to his last dying breath. The fight is over.

Well, not exactly

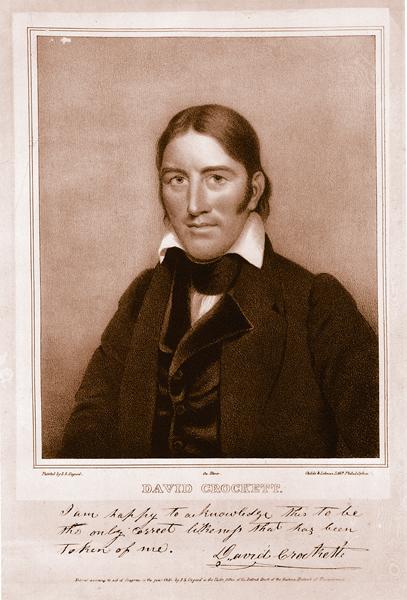

That’s how we in the United States celebrated the death of “The King of the Wild Frontier” for a good part of the 20th century. Exemplifying the Texas creed that you have no business telling a story unless you can improve it, David’s death scenario just kept growing each time the story was retold. (He referred to himself as David, says Alamo historian Alan C. Huffines, who was also a military advisor for Touchstone Pictures’ 2004 The Alamo, see p. 60.)

Then, in 1955, at the height of the Disney Davy’s fame, a purported memoir from Mexico surfaced that had the audacity to claim Crockett had sur-rendered. It wasn’t until an English translation was released in 1975 that the José Enrique de la Peña memoir was belittled and rebuked. But as historians took a closer look at corroborating evidence, Crockett’s dramatic finale began to change.

Let’s take a look at the historical record:

Anglo Accounts

One of the first official reports of the Alamo fight comes from Gen. Sam Houston, writing to the commander at Goliad, March 11, 1836: “After the fort was carried, seven men surrendered and called for Santa Anna and quarter. They were murdered by his order.”

Although Houston doesn’t name Crockett, it is reported from the beginning that a group of Alamo defenders had surrendered.

Here’s a condensed version of one of the first news reports that appeared in the Morning Courier & New-York Enquirer, July 9, 1836:

“Six Americans were discovered near the wall yet unconquered. They were surrounded and ordered by General Castrillón to surrender, which they did under a promise of protection.”

One of the six steps forward with “a bold demeanor.” The troops notice his “firmness and his noble bearing.” Undaunted, “David Crockett” steps forward boldly to face Gen. Santa Anna and looks him “steadfastly in the face.”

“His Excellency,” Manuel Fernandez Castrillón says to his commander. “Sir, here are six prisoners I have taken alive; how shall I dispose of them?”

Santa Anna looks at Castrillón fiercely and replies, “Have I not told you before how to dispose of them? Why do you bring them to me?”

Several junior officers pull their swords and lunge at Crockett and the others, the Mexicans plunging their swords into “the bosoms of their defenseless prisoners.”

Mexican Accounts

Ramón Martínez Caro, Santa Anna’s personal secretary, reports in an 1837 pamphlet published in Mexico that “there were five who were discovered by General Castrillón while the soldiers stepped out of their ranks and set upon the prisoners until they were all killed.”

José Enrique de la Peña’s memoir offers a somewhat different version: “some seven men had survived the general carnage and, under the protection of General Castrillón, they were brought before Santa Anna. Among them . . . was the naturalist David Crockett, well known in North America for his unusual adventures . . . Santa Anna answered Castrillón’s intervention in Crockett’s behalf with a gesture of indignation and, addressing himself to … the troops closest to him, ordered his execution. The commanders and officers were outraged at this action and did not support the order . . . but several officers who were around the president and who, perhaps, had not been present during the moment of danger . . . thrust themselves forward . . . and with swords in hand, fell upon these unfortunate, defenseless men just as a tiger leaps upon his prey. Though tortured before they were killed, these unfortunates, died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.”

Aftermath:?Odds & Ends

Although the David Crockett surrender scenario is still contentious, especially in Texas, author Dan Kilgore concludes, “Four officers and a sergeant—all of whom participated in the assault and observed the final tragedy—specifically identified Crockett as one of the captives.” Kilgore concludes, “Their accounts have come to light over a long period of time, several having surfaced only recently. Any one of them, standing alone, could be subject to question, but considered as a whole, the statements provide stronger documentation than can be claimed for any other incident during the battle.”

Others believe Crockett didn’t even die at the Alamo. In 1840, William White wrote a letter printed in the Austin City Gazette that reported a visit to Guadalajara, Mexico, where a native stated a Texas prisoner had been forced to work in a mine. The enslaved miner was, of course, Crockett. White claimed that Crockett had written a letter to his family in Tennessee and asked White to mail it for him. Even though the letter never arrived, David’s son, John Crockett (a congressman from Tennessee), allegedly started for Mexico to search for his father.

“Too much has been made over the details of how David died at the Alamo. Such details are not important. What is important is that he died as he had lived. His life was one of indomitable bravery; his death was a death of intrepid courage. His life was one of wholehearted dedication to his concepts of liberty. He died staking his life against what he regarded as intolerable tyranny,” wrote James A. Shackford in his 1955 book, David Crockett.

Recommended: How Did Davy Die? by Dan Kilgore, published by Texas A&M University Press and Eyewitness to the Alamo by Bill Groneman, published by Republic of Texas Press.

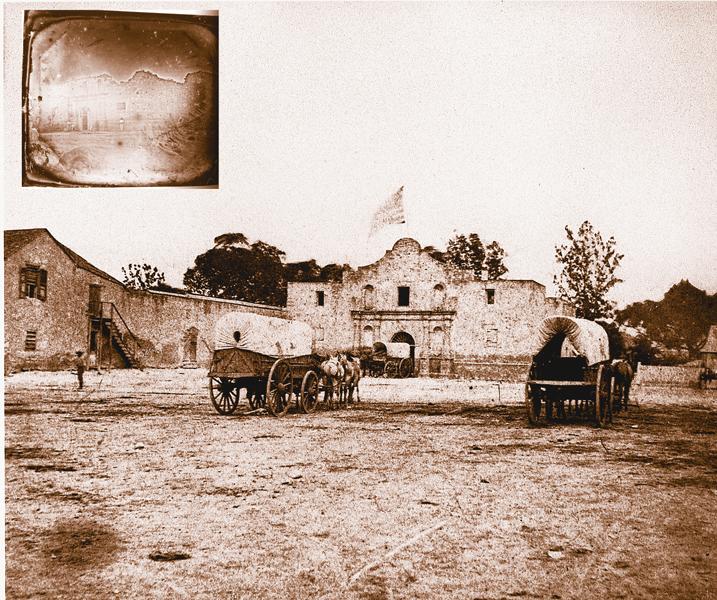

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Paul Hutton –

– Courtesy of the Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin; Below, True West Archives –

– Courtesy David Zucker –

– Courtesy Paul Hutton –