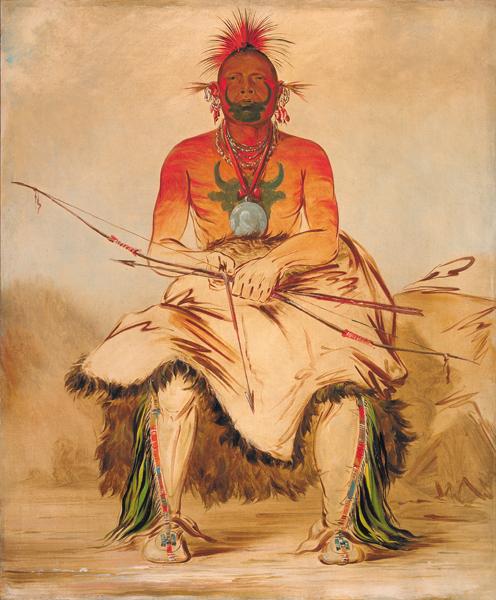

George Catlin’s paintings were predicted to “grow in importance with advancing years, and when the race of which they are the representation will have entirely disappeared, their value will be inestimable,” wrote Smithsonian Director Joseph Henry on December 13, 1873.

George Catlin’s paintings were predicted to “grow in importance with advancing years, and when the race of which they are the representation will have entirely disappeared, their value will be inestimable,” wrote Smithsonian Director Joseph Henry on December 13, 1873.

Today, the paintings’ unquestionable grandeur can be viewed from June-August 4 at the Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, California, which has on loan a portion of Catlin’s original Indian Gallery from the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, on July 26, 1796, Catlin became a lawyer in 1820, before embarking on his art career in 1832 and moving to Philadelphia. When he saw an Indian delegation, Catlin realized that an Indian could be “the most beautiful model for the painter—and the country from which he hails is unquestionably the best study or school of the arts in the world.”

The artist had been supporting himself by painting portraits. During a party at one of his patrons, Catlin met his future wife, Clara Bartlett Gregory, who he married on May 10, 1828. Two years later, Catlin embarked on his first Western journey, leaving his wife behind.

In St. Louis, Missouri, Catlin enlisted the help of 60-year-old William Clark of Lewis and Clark fame. Clark accompanied him to a few Indian treaty councils, and thereafter, Catlin’s career took off. He joined Maj. John Dougherty’s expedition up the Platte River in 1831, painting portraits of the Oto, Omaha and Grand Pawnee tribes. Catlin earned the name Ee-cha-zoo-kah-wa-kon, the Medicine Painter, after painting the Sioux around Fort Pierre (near modern Pierre, South Dakota). In 1836, after visiting Pipestone Quarry (now a national monument in Southwest Minnesota), Catlin sent a specimen to Charles T. Jackson, a Boston mineralogist, who honored the first known white man to see the quarry by naming its soft rock Catlinite.

Catlin opened his Indian Gallery of artwork and artifacts in New York’s Clinton Hall on September 25, 1837. His dream was for the U.S. Government to buy his Indian Gallery for a National Museum, but the outbreak of the Mexican War ended that hope. Six years later, a bill finally came to the floor of Congress authorizing the purchase of Catlin’s paintings, but it lost by one vote.

Catlin was a broken man by this point. His wife had died from pneumonia in 1845; his son, George, Jr., died of typhoid fever in 1847; and his three daughters were taken from him by his wife’s family when debtors called in their loans after the government refused to buy Catlin’s Indian Gallery.

In 1870, Catlin opened an exhibition featuring duplicates of his Indian Gallery (the original gallery had been given to Joseph Harrison, Jr., who paid off some of Catlin’s debts). Although the show was unsuccessful, he was invited the following year to hang his duplicate paintings where he always felt they belonged: the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Catlin died December 23, 1872, never knowing the fate of his beloved Indian Gallery. It did finally become a part of the Smithsonian’s permanent collection, but it wasn’t through an act of Congress. The heirs of Joseph Harrison, Jr. gifted the collection to the museum on May 19, 1879.

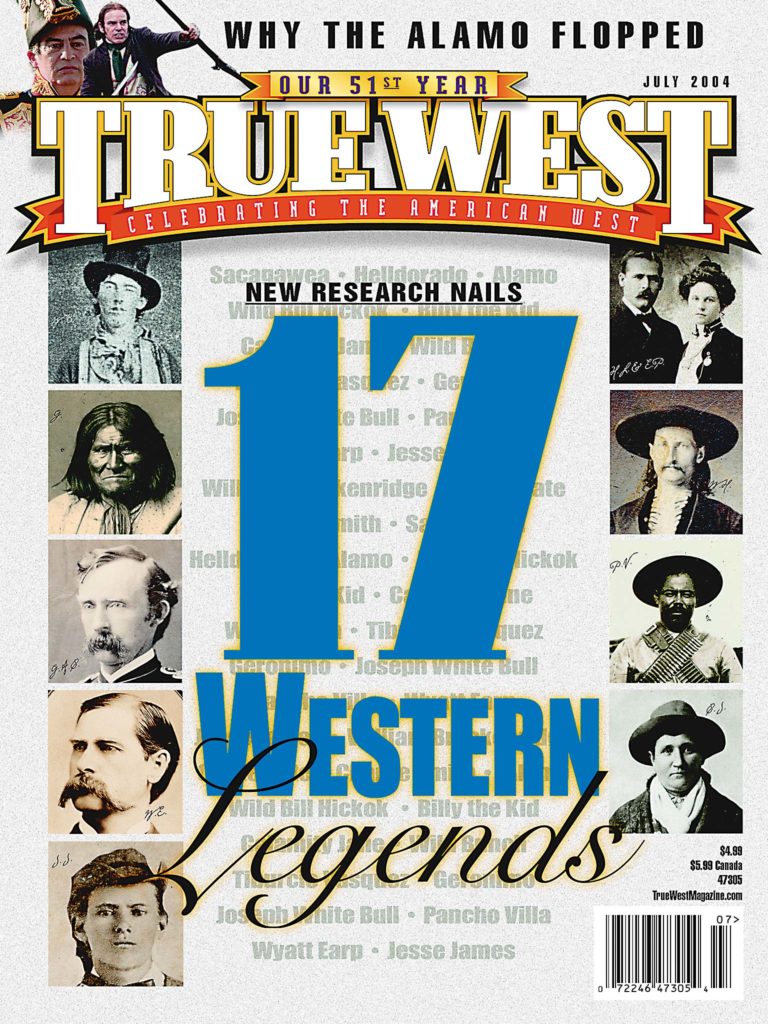

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum –