What was Juan de Oñate thinking when he named the Rio Grande in 1598? Great River? Criminy, at some places it’s not even a mediocre ditch.

What was Juan de Oñate thinking when he named the Rio Grande in 1598? Great River? Criminy, at some places it’s not even a mediocre ditch.

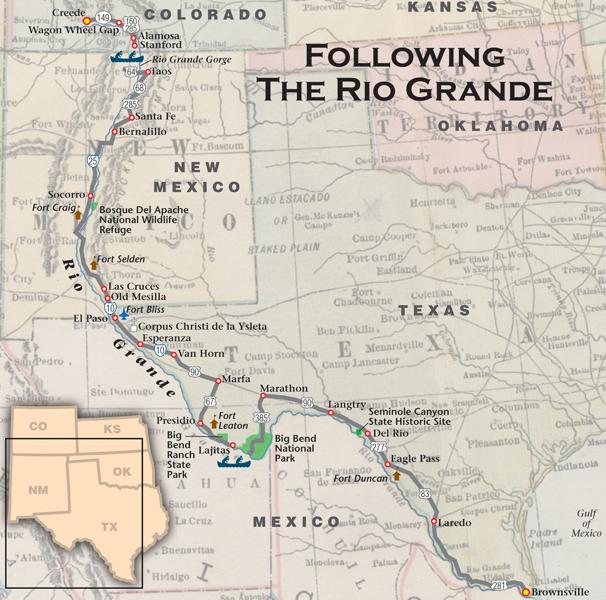

Explorers from Álvar Núñez Cabesa de Vaca (1535-1536) and Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (1540) to Lt. Zebulon Montgomery Pike (1806) and John Charles Frémont (1849) crossed it, but they never deemed it worthy of exploration. No one even thought enough of the Rio to map it until the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the 1853 Gadsden Purchase.

Before Oñate stuck the river with its current handle, it went by several names, including Rio de Nuestra Señora, Rio Turbio, Rio Caudaloso, Rio del Norte y de Nuevo Mexico, Rio de las Palmas, Rio del Norte and, down south, el Rio Bravo. Three British sailors called it the River of May in 1568. To Pueblo Indians, it was Posoge, which means Big River.

Well, since “Big River” is one kick-butt Johnny Cash tune—albeit, about the Mississippi—it’s time to punch in a tape and tame the Rio Grande on a Renegade Road—on land and water—and learn why it’s so great.

Headwaters Country: The Road

The Rio Grande certainly isn’t misnamed, as is evident when you reach its headwaters in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains along the Continental Divide. The scenery around Stony Pass, elevation 12,584 feet, is breathtaking, and it’s here—37º 47’ N, 107º 32’ W—that the river is formed by snowmelt and perpetual springs.

Scenic Highway 149 and then U.S. 160 parallel the river through Creede, Wagon Wheel Gap (where Tom Boggs, fur trader Kit Carson’s brother-in-law and no apparent relation to this hack writer, farmed in 1840) South Fork and Monte Vista to Alamosa.

The off-the-river highlight is Creede. When a silver vein was discovered in 1890, 10,000 prospectors descended into the canyon. In two years, $1,000,000 worth of silver had been shipped, but the boom ended with a wicked fire in 1892 and the Panic of ’93. For a look at Creede’s historical past, drive the 17-mile Bachelor Historic Tour and take a walk through town. Make sure you visit the Creede Historical Society and Museum and the Underground Mining Museum.

South of Alamosa near Stanford is Pike’s Stockade State Historical Monument (open in the summer season only), which has been reconstructed using Pike’s journals. Despite the glory he now gets, Zeb Pike wasn’t so hot as an explorer. Heck, he built the stockade in 1807 because he got lost, accidentally stumbled into Mexican territory and had to wait out the winter.

Ute Mountain Run: The River

Just north of the New Mexico border, I give up the road for a canoe. Wally Cox, master paddler from Dallas, assures me we’ll have a nice float trip through Class II rapids.

What does Wally know?

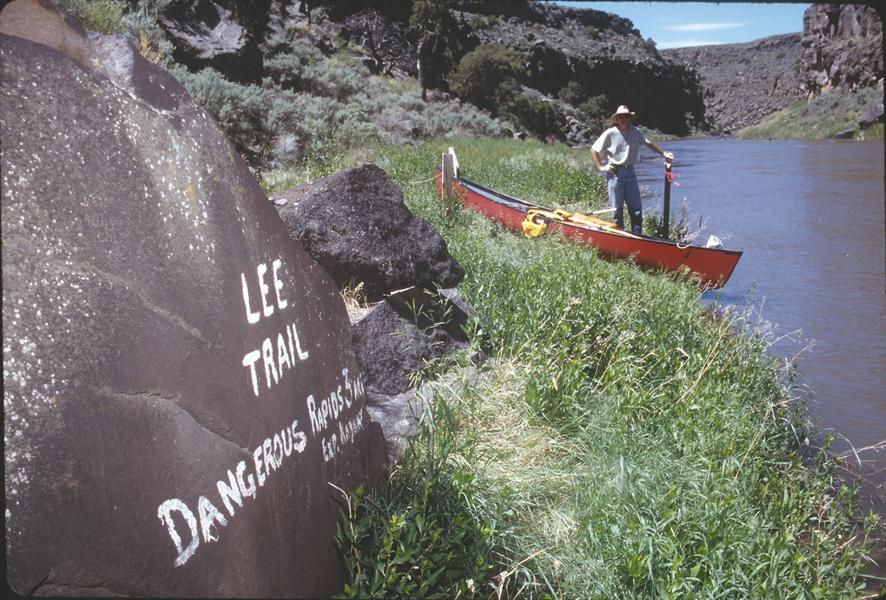

The river shows its power as it cuts a gorge that gets deeper as we journey south. Few people take the 24-mile Ute Mountain Run to Lee Trail—with good reason, too, we’ll soon learn.

This is one of the most pristine sections of the river, with towering canyon walls, falcons, bats—a birder’s paradise. Elk watch us from the banks, then plunge into the river and swim across, wary of our approach.

Class II rapids are typically easy to maneuver. We come close to swamping Wally’s canoe only once. What makes the run difficult is the wind. Deep in the canyon, the wind pushes us back and from side to side but never downstream. Paddle-paddle, pant-pant, paddle-paddle, pant-pant-pant. We’re an exhausted pair of canoers that night when we camp halfway from the takeout at Lee Trail, wondering how bad it’ll be tomorrow.

How bad? Have I mentioned that the takeout is a quarter mile of switchbacks up a steep, unimproved trail? Class II rapids, sure, but the takeout is a treacherous Class VI.

Being hardy 21st-century voyageurs, Wally and I succeed and drive into Taos, agreeing that Ute Chief Ouray and Kit Carson probably never traveled that part of the river. They were a lot smarter than we are.

With my arm muscles screaming from continual paddling, it’s time to recuperate. For the next two days, my diet will consist of Gatorade and Ibuprofen.

Taos to El Paso: The Road

Taos is a fine place to recover. You can get a feel for the frontier at the excellent Kit Carson Home & Museum and La Hacienda de los Martinez, a restored Spanish Colonial rancho. Even if you don’t like art—why are you in Taos?—stop off at the Millicent Rogers Museum and the Harwood Museum of Art. Before leaving Taos, take a bird’s-eye view of the river from the bridge over the Rio Grande Gorge (U.S. 64), then follow the River Road to Santa Fe.

From New Mexico’s capital, it’s an easy course along the river down Interstate 25. In Bernalillo, take time to visit restored Pueblo ruins and the interpretive trail at Coronado State Monument. When he searched for the Cities of Gold, Coronado camped here in 1540.

The next great river stop is south of Socorro at Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge, a popular 57,191-acre sanctuary. Just down the road are the remote ruins of Fort Craig National Historic Site. Five miles north of the fort, Confederate forces commanded by Gen. Henry H. Sibley engaged Col. E.R.S. Canby’s soldiers at Valverde Ford in 1862. The Rebels won the day and marched north before being turned back after the battle of Glorieta Pass, near Santa Fe.

A self-guided interpretive trail takes me around the desolate fort, but before you hazard a trek here, check road conditions.

Much more accessible is Fort Selden State Monument at Radium Springs north of Las Cruces. The fort had a short life. Founded in 1865, it was abandoned in 1877, reoccupied in 1882 during the Apache Wars and then permanently abandoned nine years later.

Like Fort Craig, the adobe walls have not fared well, but Selden features an excellent museum that pays tribute to the Ninth Cavalry buffalo soldiers stationed here during the Apache campaigns.

Two other important stops are the New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum in Las Cruces and the historic plaza in Old Mesilla, where, in 1881, Billy the Kid was tried for Sheriff William Brady’s murder.

Now it’s time to follow the river into Texas.

El Paso to Big Bend: The Road

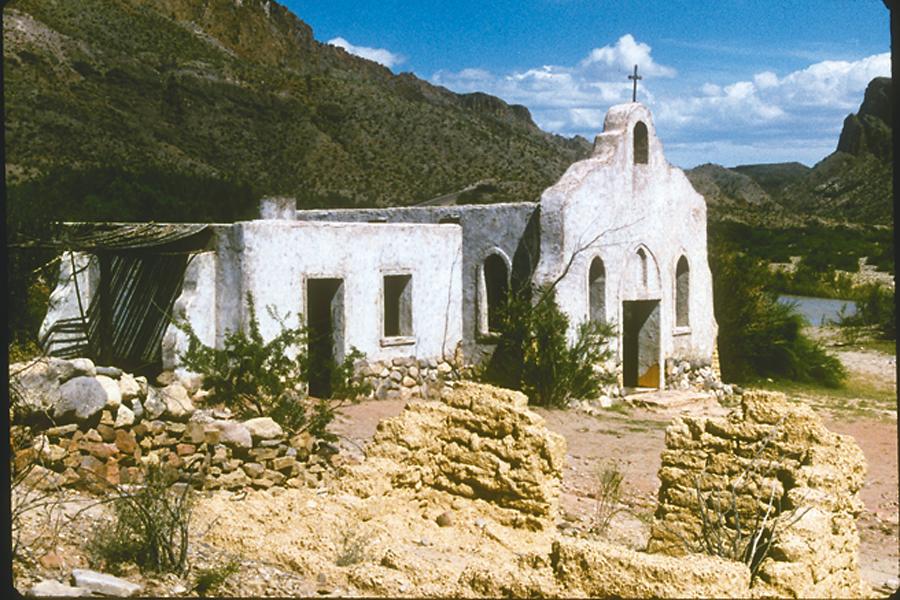

Out in the West Texas town of El Paso, take the mission tour, or if you’re pressed for time, just see the Corpus Christi de la Ysleta, the oldest mission in Texas, circa 1681. Fort Bliss offers the Air Defense Artillery Museum, Museum of the Noncommissioned Officer and Fort Bliss Museum, while the El Paso Museum of History displays a wide array of exhibits from the military to Pancho Villa. Just off I-10, you’ll find Concordia Cemetery, the final resting place of John Wesley Hardin and a who’s who of other not-so-nice gunfighters.

Fill your belly with Tex-Mex chow before heading east on I-10. At Esperanza, we’ll leave the river for Van Horn, then travel south on U.S. 90 to Marfa—where the 1956 movie Giant was filmed—and south on U.S. 67 to Presidio and the Rio Grande. At Presidio, spend time at Fort Leaton, a superb reconstruction of the sprawling adobe compound built by Ben Leaton in 1848. Historians agree that Leaton wasn’t a nice guy, but folks at this state historic site speak Texas-friendly.

From Presidio, I follow the roller-coaster river road through the massive Big Bend Ranch State Park to Lajitas, where I once more leave the highway for the river.

Big Bend: The River

Our guide calls himself Bobski, and I start having doubts about this raft trip. Big Bend is populated with society dropouts and dropouts who have never belonged to any society. But Bobski—“Just Bobski,” he says, when my wife asks for his last name—assures us that he is a capable guide.

And he is.

The river’s low, the Class II rapids barely get you wet and salt cedar ruins much of the scenery, but the float trip into Big Bend National Park is certainly worthwhile.

“That’s Outlaw Cave,” says Bobski, pointing out a cavern high in the rocky canyon wall. “Seems like a dumb name for a hideout. Imagine a posse chasing the outlaws: ‘Where do you think they went?’ ‘I dunno. Let’s try Outlaw Cave.’”

Bobski guides us through deep Santa Elena Canyon safe and sound, and we’re soon free to explore one of America’s most underrated national parks.

Big Bend to Brownsville: The Road

It’s time to leave the river again, drive up U.S. 385 to Marathon and then head east on U.S. 90 to Langtry, home of the Judge Roy Bean Saloon & Museum and now a Texas Visitor Center, which preserves Bean’s saloon, courthouse, billiard hall and opera house. Bean is buried near Whitehead Memorial Museum in Del Rio, but before I reach that city, I want to view the 4,000-year-old rock art at Seminole Canyon State Park, located at the confluence of the Rio Grande and the Pecos River, so I?set up camp there.

From Del Rio, the river cuts south through Eagle Pass, which is home to the museum of circa 1849 Fort Duncan, and Laredo.

My next stop is Brownsville, home of the Stillman House Museum and Historic Brownsville Museum. Nearby are the battlefields at Palmito Ranch, the last engagement of the Civil War, fought a month after Robert E. Lee’s surrender; and Palo Alto, where on May 8, 1846, Gen. Zachary Taylor’s artillery proved more effective than that of Gen. Mariano Arista, thus beginning the Mexican-American War.

The Rio Grande ends its 1,800-mile journey a few miles south at the Gulf of Mexico, and it’s hard not to appreciate the 22nd-longest river in the world. After you’ve traveled the course, you’ll probably have a different view of the Rio Grande. I do.

Juan de Oñate did know what he was talking about. The Rio Grande is unpredictable—violent rushing water in some places, a mere trickle in others. It’s wild and scenic, and a river of controversy with water rights still raging. It’s a river of history, too. Great history.

Yep, the Rio Grande is aptly named.

Johnny D. Boggs recommends that if you take an overnight canoe or rafting trip down the Rio Grande, hang your bear bag before you start sipping brandy.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs –