With all the pomp the Spanish officer could muster so far from present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico, Lt. Facundo Melgares rode into the sprawling Pawnee village along the Republican River in Nebraska in 1806 with 300 uniformed men.

With all the pomp the Spanish officer could muster so far from present-day Santa Fe, New Mexico, Lt. Facundo Melgares rode into the sprawling Pawnee village along the Republican River in Nebraska in 1806 with 300 uniformed men.

The Pawnee village had a population of nearly 1,000, among the estimated 10,000 Pawnees who resided in Nebraska. Melgares’s orders were to keep the peace. North of him, near present-day Columbus, a Spanish force under Gen. Pedro De Villasur had fallen to Pawnee warriors in 1720.

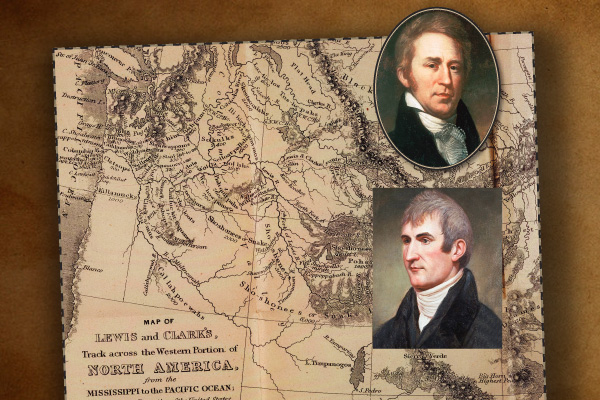

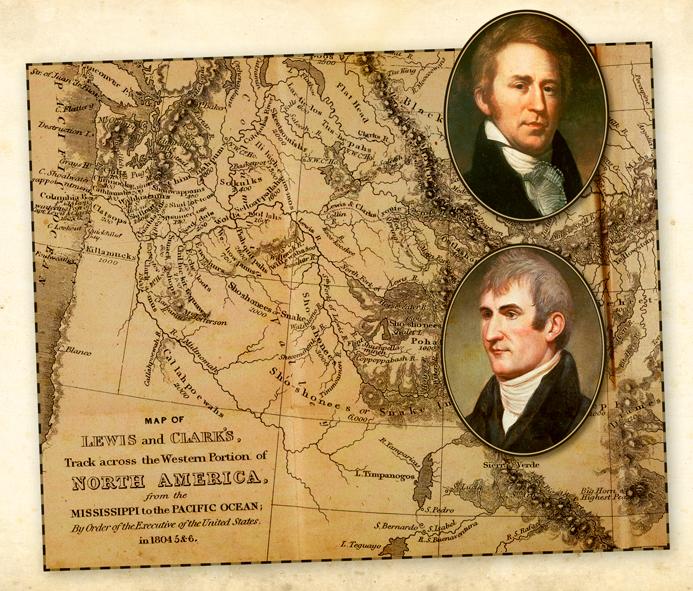

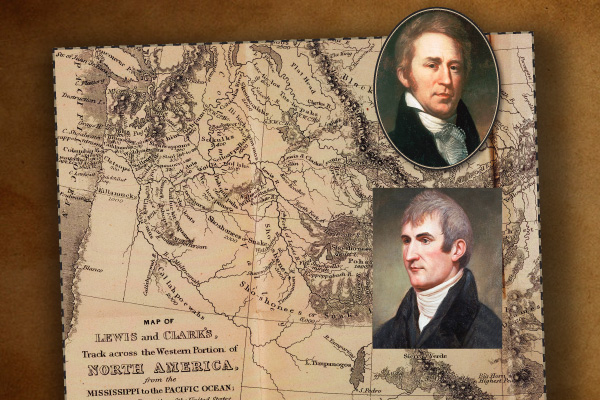

Melgares’s mission was to arrest Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as the explorers made their way back to the United States after trespassing in Spanish territory. Spain did not recognize France’s 1803 sale of the territory to the U.S. since, when Spain sold the territory to France three years earlier, Spain had stipulated it could not be sold to a third party without prior consent.

Spanish fur traders had been working the upper reaches of the Missouri River for decades. Spanish commander Pedro Vial had a map of the West dated 1787 that not only showed the entire course of the Missouri River, but also its source at Three Forks in western Montana. Lewis and Clark would not come across Three Forks until 1805.

After the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, President Thomas Jefferson launched four expeditions into the vast region: Lewis and Clark were to explore the northern region by following the Missouri River; Zebulon Pike was to explore the central region by following the Kansas River; and William Dunbar, ascending the Ouachita, and Thomas Freeman, by way of the Red River, were to explore the southern portion.

When Gen. James Wilkinson, commander of the U.S. Army and a traitorous paid agent of Spain, obtained details of these expeditions (his son James was assigned to the Pike expedition), he passed them on to the Spanish ambassador, Marqués de Casa-Yrujo.

The Spanish ambassador urged Nemesio Salcedo, commandant general of the Internal Provinces, to intercept the expeditions. Vial, the premier mountain man of his time, having lived amongst the fierce Comanche, was the logical man to send out after the Americans.

On August 1, 1804, Vial and Jose Jarvet led 52 Spanish troops and Pueblos out of Santa Fe. Arriving in central Nebraska, Pawnees informed Vial that Lewis and Clark were already ascending the Missouri River. They were less than 100 miles from Vial’s position, but for some unknown reason, Vial returned to Santa Fe.

Salcedo sent Vial to find Lewis and Clark a second time, on October 5, 1805, with 100 men. They encountered armed Indian warriors near today’s Las Animas, Colorado, and, after a give-and-take fight, returned to Santa Fe,

New Mexico.

For a third time, Salcedo sent Vial after the explorers, in April 1806, with 300 men and trade goods for the Pawnees. This time, Vial turned back due to desertions.

Given Vial’s poor results, Salcedo asked the aristocratic Melgares to locate Lewis and Clark before they reached the safety of the United States.

Melgares left Santa Fe on June 15, 1806, with 600 troops. Reaching the Arkansas River near present-day Larned, Kansas, he had 240 men dig in, anticipating the Freeman expedition. Then he and the others aimed north for the Missouri River.

When Melgares arrived at the Pawnee town on the Republican in September, Chief Sharitarish, also known as White Wolf, animatedly opposed the Spanish continuing on. With Lewis and Clark entering the Nebraska area, Melgares was only 140 miles from his quarry. But he risked an armed confrontation with White Wolf if he continued on.

The best he could do was convince the Pawnee chief to fly the Spanish flag and to not allow Americans onto Pawnee lands. He also gave White Wolf Jarvet’s 10-year-old half-Pawnee son and two French trappers whom he had arrested. Melgares began the march back home around September 11.

Two weeks later, Pike and his 20 men arrived. The Pawnees were hostile, so as to honor their agreement with Melgares. Pike calmed them; he even persuaded them to lower the Spanish flag and raise the U.S. flag.

White Wolf opposed Pike going west. Pike ignored his warning and followed the trail left by Melgares to the Arkansas River, where Pike struck west. The Spanish captured Pike and his men on February 26, 1807, and escorted them to Santa Fe, though they were eventually released.

Freeman was also turned back by Spanish authorities at Spanish Bluff near the Oklahoma border in July 1806. But the Spanish never stopped Lewis and Clark.

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. He currently resides in Enid, Oklahoma, and he teaches in Tuluksak, Alaska, part of the year.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

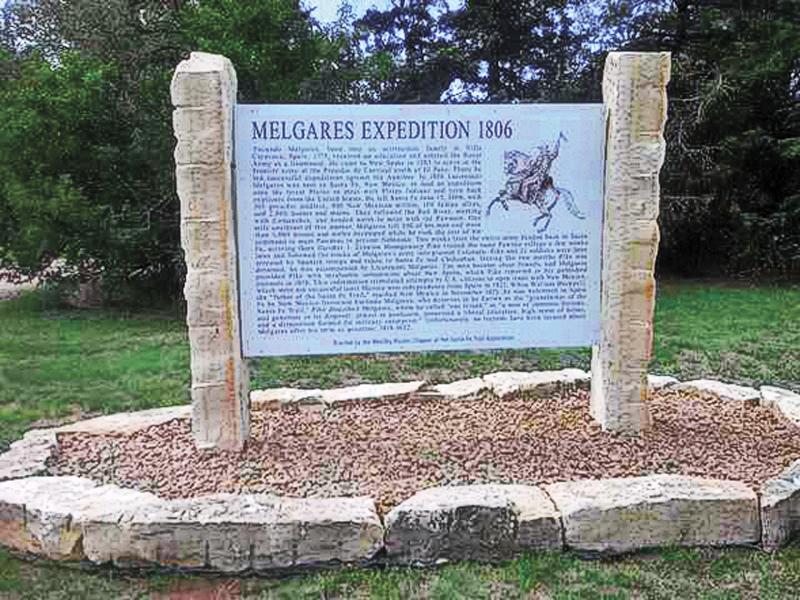

On September 18, Larned, Kansas, dedicated a sign marking the Melgares Expedition and the site where Melgares had left his men to capture an American expedition while he rode to Nebraska to arrest Lewis and Clark. The marker is four miles west of Larned off U.S. 56.

– Courtesy Santa Fe Trail Association –