Bob Wright, one of the earliest residents of Dodge, who stayed on to become the town’s most prominent businessman and political figure, related this first story in his book Dodge City, The Cowboy Capital, published in 1913.

Bob Wright, one of the earliest residents of Dodge, who stayed on to become the town’s most prominent businessman and political figure, related this first story in his book Dodge City, The Cowboy Capital, published in 1913.

Bat Masterson was admired by men for his daring exploits as a buffalo hunter, army scout and lawman, but, as a “well dressed, good looking, perfectly-made man,” he was irresistible to women, who played a large part in the dramatic events of his life.

A woman was a major figure in a bloody shoot-out at the U. S. Army cantonment at Sweetwater, Texas, on the night of January 14, 1876—an event that would become the foundation upon which Masterson’s widespread notoriety as a gunfighter was based. That night Army Corporal Melvin King and civilian army employee Bat Masterson fought to the death with sixguns. A dancehall girl named Mollie Brennan, over whom, by most accounts, the fight was waged, died in the exchange of bullets. In a jealous rage over Mollie’s evident preference for Bat, King is said to have confronted Masterson and the girl in the Lady Gay saloon. As he brandished a pistol, Mollie jumped between the men, in an effort to prevent gunplay. King’s first bullet, a bullet through his mid-section, knocked Masterson to the floor, A second shot struck Mollie and she crumpled, mortally wounded. Bat had his gun out now and, while prone on the floor, killed King with a single shot.

Little is known of Mollie Brennan who died in that roar of gunfire and whose name would be forever linked with the famous Bat Masterson. She reportedly worked as a prostitute in Denison, Texas, before moving on to Ellsworth, Kansas, when that town was enjoying its brief boom as the terminus of the Texas cattle trail. There she hooked up with saloonman Joe Brennan and took his name in a common-law marriage. She later lavished her affections on Billy Thompson, the troublesome younger brother of well-known Texas gambler and gunfighter, Ben Thompson. Late in 1875, Mollie followed Billy Thompson to Sweetwater where he had an interest in a dance hall, and there she met her ultimate destiny.

No charges were brought against Masterson by either the army or civilian authorities for the affair, and, after recovering from his wound, he showed up in Dodge City, where he soon pinned on a lawman’s badge. In 1877, at the age of 24, he was elected sheriff of Ford County, Kansas, headquartered in Dodge. The following year the murder of another well-known woman led to a legendary exploit. The featured singer at The Varieties, a combination saloon, theater and concert hall in Dodge, was Dora Hand, billed as “Fannie Keenan, The Queen of the Fairy Belles.” By all accounts Dora was a beautiful and talented woman. She had appeared in a succession of frontier towns where, according to no doubt exaggerated reports, her charms had precipitated gunfights in which 12 men died. No reliable sources ever linked Bat with Dora romantically, but the handsome young sheriff and the beautiful stage performer were well acquainted, and when she died needlessly at the hands of a wanton killer, Masterson, enraged, was quick to lead a successful search.

James “Spike” Kenedy was the ne’er-do-well son of Mifflin Kenedy, one of the wealthiest and most successful cattle ranchers in Texas, for whom both a town and county were named. In Dodge, young Kenedy got into an altercation with Jim “Dog” Kelley, saloon owner and mayor of the town. The city police told him to “get out of Dodge” and he left, but vowed vengeance. In the early morning hours of October 4, 1878, he again rode into town astride a thoroughbred racehorse and headed straight for the small frame dwelling where he knew Dog Kelley lived. Drawing a Winchester rifle from the scabbard, he deliberately fired four shots into the building, then put spurs to his mount and thundered out of town. What he did not know was that his hated enemy, Kelley, had taken sick a few days before and was then under treatment at the post hospital in Fort Dodge, five miles away. During his absence he had turned over his little two-room cottage to Dora Hand and another variety hall entertainer, Fannie Garretson. Spike Kenedy’s murderous fusillade intended for Kelley resulted only in the death of Dora Hand, who was struck by one of the bullets as she slept, killing her instantly.

Sheriff Masterson organized what the Dodge City Times called “as intrepid a posse as ever pulled a trigger,” including City Marshal Charlie Bassett, Assistant Marshal Wyatt Earp, and Deputy Sheriffs Bill Duffey and Bill Tilghman who rode out on the trail of the murderer. By good guesswork as to his route of flight and much hard riding, Masterson’s posse was able to reach the Cimarron River before Kenedy arrived. There they set up an ambush at the crossing. When the fugitive appeared, he ignored Bat’s calls to halt and tried to flee, but posse bullets killed his horse and one big slug from Masterson’s buffalo rifle smashed his arm. When they pulled him from under his dead horse, Bat later said, they “could hear the bones crunch.”

“Did I kill that bastard Kelley?’ Kenedy wanted to know. When he was told that Kelley was fine and he had only succeeded in killing Dora Hand, Kenedy blanched. Then, seeing the buffalo gun in Bat’s hand, he snapped: “You damn’ son-of-a-bitch! You ought to have made a better shot than you did!”

“Well, you damn’ murdering son-of-a-bitch,” Bat retorted, “I did the best I could!”

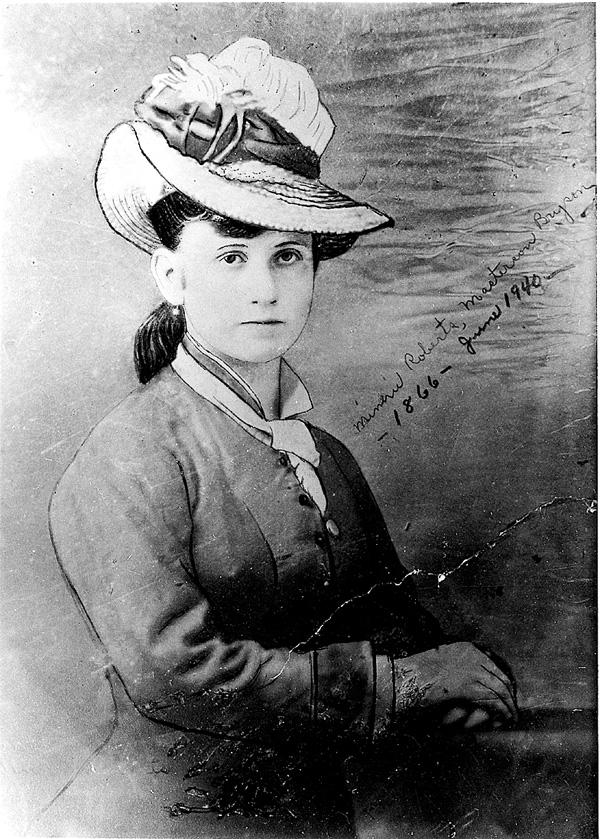

During his term as sheriff at Dodge City, the local papers contained several oblique references to Masterson’s consorting with the ladies. There was a social item in June 1878 mentioning the attendance of “Sheriff Masterson and lady” at a gala in neighboring Spearville, and the appearance of “W. B. Masterson and Miss Brown” at a grand masquerade ball in Dodge City that Christmas. The 1880 census taken in Dodge indicated that he was cohabiting with one Annie Ladue, aged 19, occupation “concubine,” who was “keeping house.” Beyond this stark reference, no information has sur-faced regarding Miss Ladue. Bat’s brother Jim, city marshal of Dodge, was enumerated in the same census as living with one Minnie Roberts, 16 years old and also acting as housekeeper and concubine. According to gossip around Dodge, Bat took a shine to Minnie and trouble developed between the two brothers over her.

Any difficulty he had with Jim over Minnie Roberts did not prevent Bat from hurrying almost a thousand miles back to Dodge from Tombstone, Arizona, in April 1881 when he was informed by telegram that enemies were conspiring to murder his brother. At noon on April 16, Bat swung down from an eastbound train and within moments was involved in a gunfight with A. J. Peacock and Al Updegraph, Jim’s adversaries, who had learned of Bat’s coming and were waiting. When they spotted him, Peacock and Updegraph ran behind the heavily timbered calaboose and opened up with pistols. Bat dropped behind the railroad embankment and returned their fire. Soon friends of both sides were shooting from positions on either side of the tracks. When the shooting was over, Peacock and Masterson were unscathed, but Al Updegraph had a bullet through his chest. He survived. Bat was fined $8 for discharging a pistol within the city limits, and before the day was over he and brother Jim had departed Dodge.

They both landed in Trin-idad, Colorado, where many members of what newspapers were calling “The Dodge City Gang” had congregated. They took law enforcement pos-itions there, but the brothers were never again close. Minnie, now calling herself “Minnie Masterson,” although no record of a legal marriage has ever surfaced, was still with Jim and would remain with him until his death from consumption in 1895. She later took up with an Oklahoma rancher named Joe Bryson. Minnie Roberts Masterson Bryson died in Liberal, Kansas, in the 1940s.

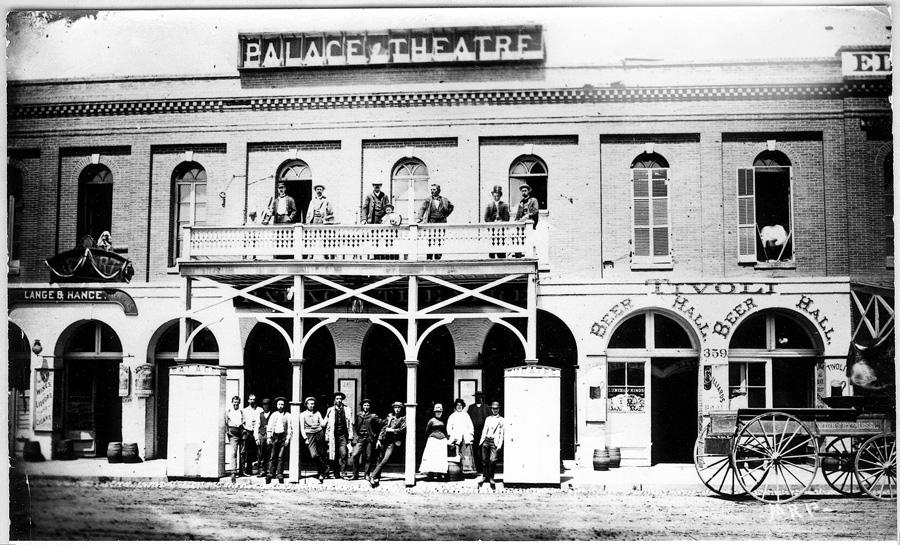

By the early 1880s, the name of Bat Masterson was well known in the West. Although he took occasional peace officer jobs, his major occupation was gambling. He was a prominent member of the “sporting” crowd, the denizens of the saloons and honky-tonks, the dancehalls and theaters, the gambling halls and brothels, that were the frontier’s playgrounds. For a time he managed the Palace Theater in Denver, called by one irate clergyman “a death-trap to young men, a foul den of vice and corruption.” There he had op-portunity to consort with many vivacious and attractive en-tertainers, keeping company with such beauties as Maggie Cline, Lottie Rogers, Effie Moore, Ettie St. Clair and Cora Vane.

In rival Denver establishment, the California Hall, he became involved with an attractive young singer, late of the Kate Castleton Opera Company, who performed under the name Nellie McMahon. The liaison ultimately led to Bat receiving his second and final gunshot wound. It seems that Miss McMahon was married, and her husband, a minstrel comedian named Lou Spencer, found nothing humorous about his wife carrying on with “W. B. Masterson, a handsome man, and one who pleases the ladies,” as the Rocky Mountain News described him. When Spencer found his wife perched on Masterson’s knee in a theater box he took instant umbrage. After a scuffle in which Bat rapped the comedian over the head with his pistol, both men were arrested, but a magistrate quickly released them with only an admonition to carry the difficulty no further. A few days later, Nellie filed for divorce and, according to the Denver newspapers, “eloped” with Masterson to Dodge City.

Bat was soon back in Denver, however, where he learned that Spencer, assuaging his matrimonial sorrows in an opium den, had been arrested and bailed out by a man named Bagsby. Aiding an enemy was a personal affront to Bat, and when he ran into Bagsby in Murphy’s Exchange Saloon, he first belabored him with invective and then the barrel of his revolver, cracking him on the cranium with his six-shooter as he had Spencer. Bar patrons made a rush for the exits. A shot rang out. When police arrived they found Bagsby nursing his bloody head at the bar, and Masterson in a back room on a table, under treatment for a gunshot wound in the leg. By all accounts the shooting was accidental, caused by the pistol of a man named Scott Judy, who dropped it during the crowd’s mad exodus. No charges were filed and there the matter ended.

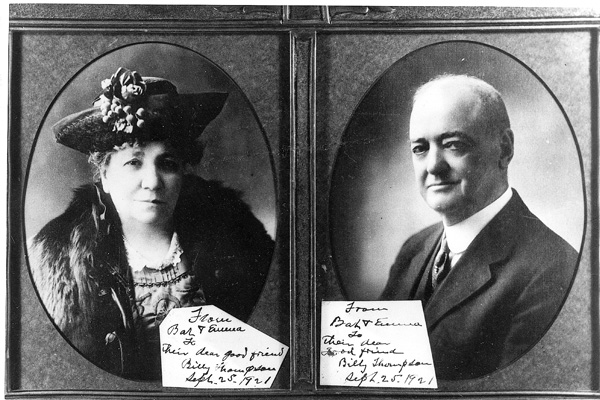

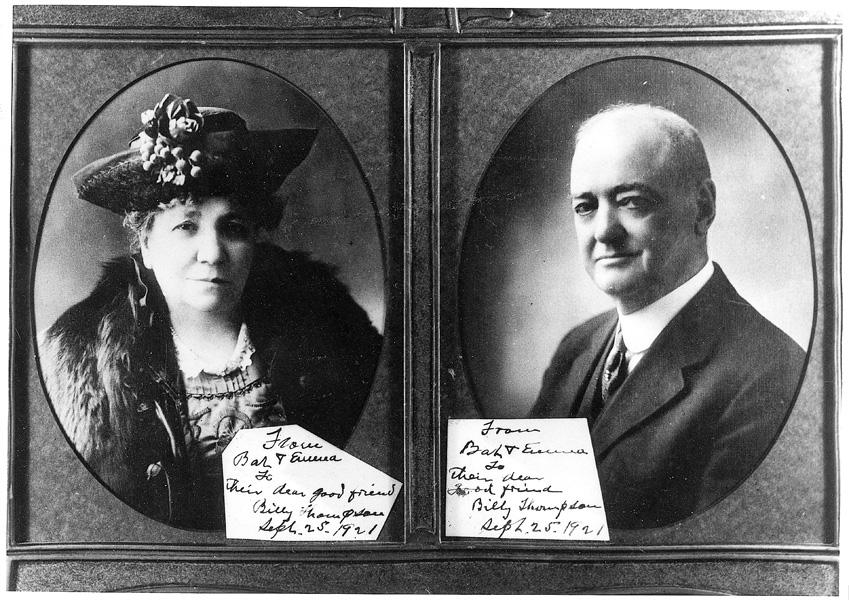

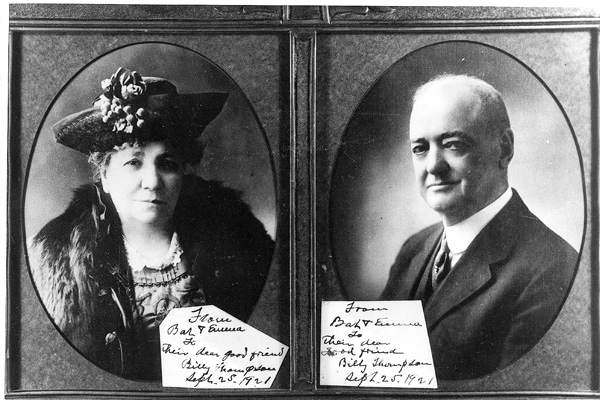

Masterson did not marry Nellie McMahon as the Denver papers suggested, but about this time he established a marriage of sorts with another theatrical performer, a blond song-and-dance girl at the Palace named Emma Walter. The daughter of a Philadelphia teamster who died a Union soldier during the Civil War, leaving his widow and children in dire financial straits, Emma took to the stage at an early age. By the time she met Bat Masterson in Denver in the mid-eighties she was almost 30 years old, a widely traveled veteran of the boards, who had undoubtedly been courted by many men. But she, like many women before her, was strongly attracted to the dashing sporting man and frontier celebrity. Soon the two were keeping house. One of Bat’s brothers told an interviewer years later that Bat and Emma were married in Denver in 1891, but no record of a formal union has been found, and it is believed the couple lived together in a common-law marriage arrangement. At any rate, once he settled down with Emma, Bat Masterson’s oats had all been sown, and his name was never again connected to another woman. They lived together as man and wife for more than 30 years, until he died at his newspaper desk in New York City in 1921. Emma followed him in death 11 years later. They are buried together in New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery.

Robert K. DeArment, the “master” on Masterson, World War II veteran, author of several books and member of NOLA since 1979, is also a contributing editor to True West. He lives with his wife Rose in Sylvania, Ohio.

Photo Gallery

– Denver Public Library –

– Author’s Collection –