Tens of thousands of people organized at Independence Square in Independence, Missouri, to follow the Oregon Trail in the 19th century.

Within sight of the present downtown district, people bought and sold mules and oxen, and they traded for wagons and supplies in anticipation of a 2,000-mile cross-country journey that would take them to new homes they would carve out of the Pacific Northwest.

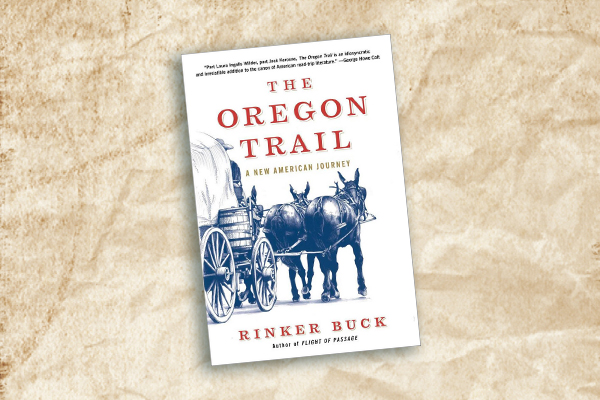

I’ve been across the entire route in a vehicle, and much of it in a wagon, and I can say if you need to get from Point A to Point B quickly, by all means, use a car or truck. But if you really want to see and experience the trail, find another way to travel. I recognize that not everybody has a wagon, nor the mules, horses or oxen to pull it, but there are other “slower” modes of transportation that will still give you a good sense of the trail … such as bicycles. And what better month to bike the trail than in May, National Bike Month?

The Oregon Trail is clearly marked for bike riders, who can follow the “auto route,” with its signs spaced periodically to keep you on track. The National Park Service has also developed auto tour booklets for much of the route that can be used for reference and planning, as you pedal your way from Independence to the Willamette Valley.

Independence Square

It’s an easy ride of less than a mile from Independence Square to the National Frontier Trail Center and the headquarters of the Oregon-California Trails Association in Independence. At the Trail Center you can pick up maps, brochures and other literature (including reference books), as well as get a good overview of the trail route and its history before crossing through Kansas City.

The trail cuts across northeast Kansas and will give your legs a workout as you go up and down the hills, climbing out of the Missouri River Valley before following the Blue River.

Nebraska’s Ruts

If you follow the auto tour route, you have roughly 400 miles of pedaling ahead of you as you cross Nebraska. The route wiggles north and west from Fairbury to Minden, where a good stop is at the Pioneer Village, an eclectic museum of Americana collected by Harold Warp.

Continuing north and west to Fort Kearny, you’ll be ready for a break to rest and restock supplies, which is exactly what the pioneers did a century and a half ago. The 1848 fort is now a Nebraska State Historic Site.

For a short detour, cross I-80 and turn your bike to the east to visit the Great Platte River Road Archway monument. This structure literally straddles I-80. You’ll “ascend” the trail via an escalator, and then you’ll take a trip across the route as you walk over the interstate (though when you are in the center you won’t even realize that the transcontinental traffic is whizzing beneath you).

Head your bike west again, following U.S. Highway 30—the Lincoln Highway. Now near the Platte River, you will have the advantage of shade from tall cottonwoods and stands of cedar trees, and you are likely to see mule deer, white tail deer, wild turkeys, bald eagles and hawks. Should you happen to be here in early spring, roughly mid-February to mid-April, you will see thousands of Sandhill Cranes, as they migrate through the region.

Farmland shifts to range country as you spin away from Highway 30 onto U.S. 26, passing California Hill. Take a break and park the bike so you can hike the trails at Windlass Hill (the first steep descent the pioneer wagons faced). As Helen McCowen Carpenter wrote on June 23, 1857, the hill made her feel “that we were ‘between the Devil and the deep sea.’” She could clearly see that, in the past, wagons had been let down with ropes, leaving behind deep ruts in the land. Some travelers “left their tracks in the sand and like a band of sheep the rest followed….”

Riding along the Platte River Valley west of Windlass Hill, the early travelers kept their eyes fixed on the horizon to catch their first glimpse of towering Chimney Rock and Scotts Bluff. The sight of these mammoth rock formations meant the easy part of the trip was over, and that’s pretty much true for modern-day bicyclists on the trail too.

Beyond Scotts Bluff the landscape changes again, the most obvious shift being the distances between communities. All across Kansas and Nebraska, riders can expect to be in at least one small town every 10 or 15 miles; in Wyoming, the distance between towns east of Casper could be 20 to 40 miles. Beyond Casper the distances escalate significantly—it can be up to 70 miles or more between towns.

Wide Open Wyoming

If you are planning to bicycle the route across Wyoming, it is fairly important to have support, or at least to make preliminary contact with folks along the route to provide essential items—the most important of which is water. A support group to consider traveling with is Historical Trails Cycling (HistoricalTrailsCycling.com). It conducts regular tours along the trail, taking in the entire route, or just sections of it.

Key sites to visit in eastern Wyoming are: Fort Laramie, the Guernsey Ruts and Register Cliff. West of Fort Laramie and Guernsey, you will see the first indications of the Rocky Mountains when Laramie Peak rears up to the west. But rest assured, riding will still be relatively easy, even though the elevation is beginning its gradual ascent.

Trail travelers crossed the North Platte River for the final time in the vicinity of today’s Casper. When you visit, stop by two key sites: the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center, which gives you a chance to experience what the trail was like in a wagon or a stagecoach, and Fort Caspar Museum, where you will learn about the military post and the role the Mormons played in crossing the river.

Leaving Casper, follow the pavement along Wyoming Highway 220 to Independence Rock. After you climb to that important trail marker, ride west to Devil’s Gate and then turn north on U.S. 287 to ride through the Sweetwater Valley.

Idaho’s Big Hill & River Routes

Oxen and mules strained in traces when pulling loaded wagons from the valley of the Thomas Fork of the Bear River, on what many said was the highest, longest slope on the whole trail—Big Hill. Starting down the western slope, the pioneers quickly committed to their route, yet not every wagon train took the same path; more than 20 individual ruts reveal their attempts to find a better way.

For cyclists, the route on Highway 30 is definitely still an ascent as you climb out of the Thomas Fork drainage. Then you’ll strike the summit and coast down into Montpelier, where you should take the time to visit the National Oregon/California Trail Center.

Bear River Valley, hot springs and the cool Portneuf River entice you in Lava Hot Springs, another good place to park the bike for a day or two, so you can rest up and prepare for the nearly 500-mile trail ride across Idaho, traveling through the Portneuf River Valley to Pocatello, and then continuing west to the Snake River, visiting American Falls and then seeing the country of the Thousand Springs en route to Glenns Ferry, site of Three Island Crossing. The Oregon Trail History & Education Center will tell you more about this river crossing that pioneers used up until 1869, when Gus Glenn built his ferry upstream.

To the west, Oregon beckons, especially the National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center in Baker City. Located atop Flagstaff Hill, the center affords outstanding views of the trail as it crosses through the Baker Valley.

Another road climb faces you: the ascent of the Blue Mountains. Reaching the summit, you’ll see a broad vista as you descend toward Pendleton. Take the time to visit the city’s Tamástslikt Cultural Institute, which shares the history and stories of the tribes of this region.

Next up, pedal west to The Dalles, where you’ll turn south to Tygh Valley before you set your course west again on the Barlow Road leading to the Willamette Valley. This crossing of the Cascades will make you pump harder on the climb, but the stunning views of Mount Hood will be worth all the effort.

Candy Moulton has traveled the Oregon Trail many times, writing of the journey with Ben Kern in Wagon Wheels: A Contemporary Journey on the Oregon Trail, and filming it for In Pursuit of a Dream, an Oregon-California Trails Association documentary.