On Tuesday, September 16, 1879, Fort Fred Steele’s telegrapher handed his post commander, Maj. Thomas Thornburgh, a letter.

On Tuesday, September 16, 1879, Fort Fred Steele’s telegrapher handed his post commander, Maj. Thomas Thornburgh, a letter.

Thornburgh glanced at it and turned to his adjutant, Capt. William Henry Bisbee, to tell him the news. The letter ordered Thornburgh to the Ute White River Agency to investigate a rebellion against Agent Nathan Meeker. General George Crook’s orders emphasized that the expedition was to be investigative, not punitive.

East of Rawlins, Wyoming, Fort Fred Steele, the closest military post to the White River Agency in western Colorado, still lay some 200 miles distant. Leaving about 50 soldiers at Fortification Creek, Thornburgh and about 120 of his men did not arrive at Milk Creek, the agency boundary, until September 29.

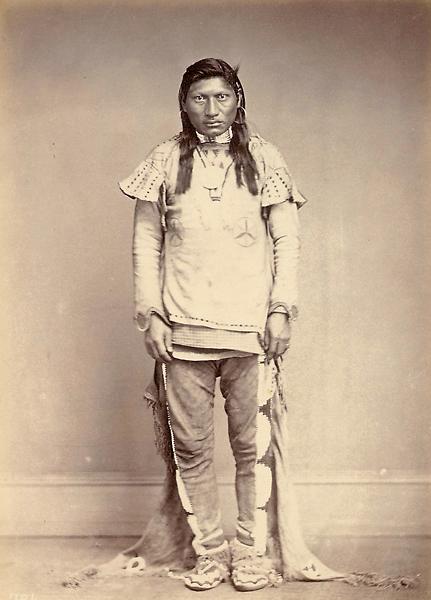

No one in Thornburgh’s White River Expedition expected the explosive reception it received, in spite of earlier warnings along the trail from Ute Chiefs Jack and Colorow to Thornburgh not to enter the Ute Agency with his entire force. They demanded only Thornburgh and five others pass south of Milk Creek. The Utes would then escort them back to the agency headquarters to talk.

Some of the major’s officers and scouts later testified that their commander had inexplicably ignored a number of adequate camp sites outside the reservation and crossed Milk Creek with two cavalry companies behind reconnaissance patrols. This heedless behavior horrified and enraged both chiefs as they watched from atop Yellow Jacket Pass.

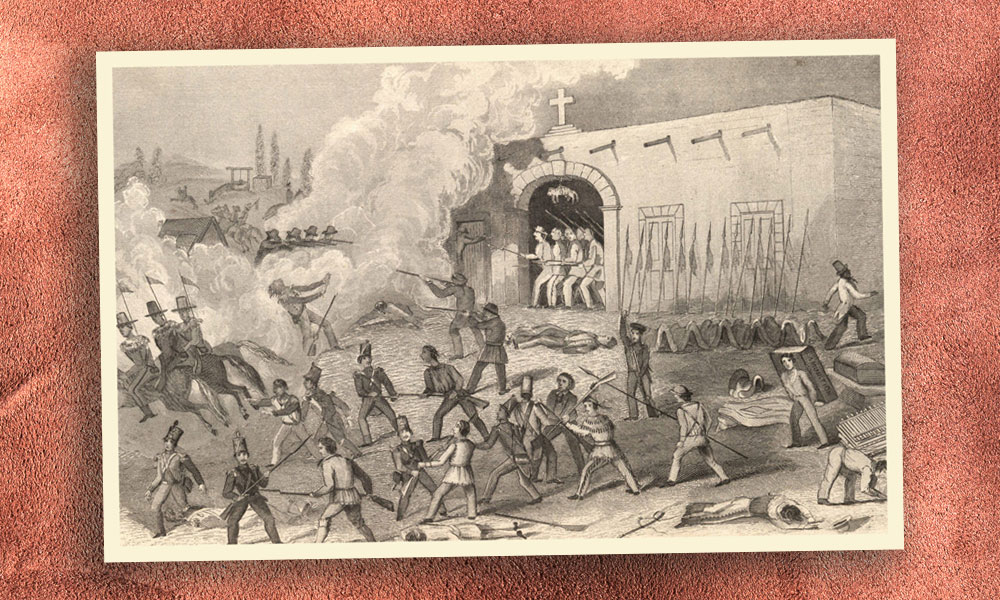

At 11:30 a.m., on September 29, Lt. Samuel Cherry, leading Capt. Joseph Lawson’s 3rd Cavalry reconnaissance patrol, took off his hat and waved it toward the Utes. A shot from a never identified rifleman followed immediately. Several breathless seconds elapsed before Yellow Jacket Pass erupted in a volcano of rifle fire. Unknown to all present, 25 miles south, the “Meeker Massacre” had also begun.

By noon, Thornburgh’s entire expedition struggled desperately for their lives. From a line of cedar trees, scrub oak and serviceberry bushes at the base of Yellow Jacket Pass blew a hail of rifle bullets. Gauging from the volume of shots and smoke, some soldiers later stated that the Utes outnumbered their men three to one. The cavalry’s reconnaissance patrols began a fighting retreat.

The Utes, utilizing the high ground to their left, immediately maneuvered to outflank the cavalry and cut them off from where Lt. James V.S. Paddock’s D Company guarded the wagon supply train on a nearly level butte above the Milk Creek. Hearing the shots, Paddock immediately circled the wagons. This action, coupled with a disciplined withdrawal of the forward detachment, literally saved the day.

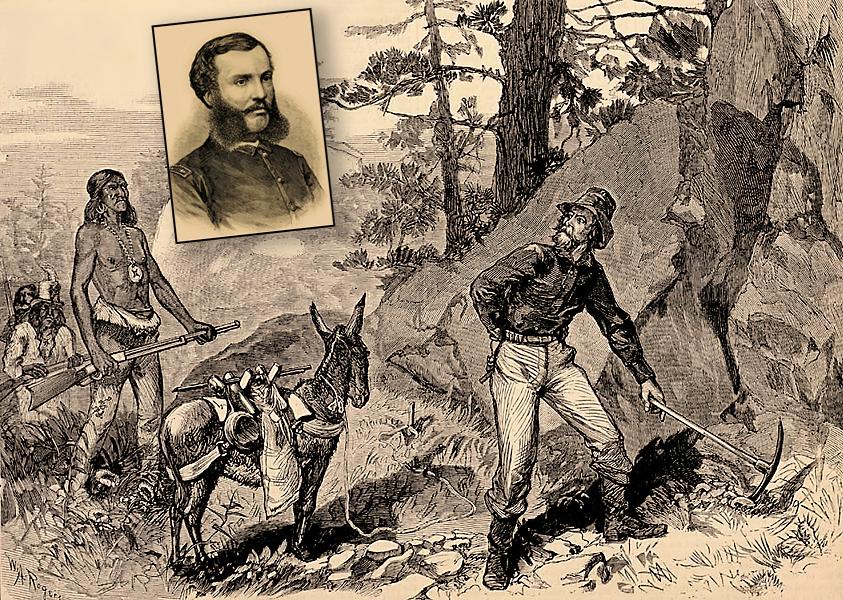

But Maj. Thornburgh lay dead somewhere in the tangle of sagebrush leading up to the tree line on Yellow Jacket Pass. His body would lie there for the next five days. Captain J. Scott Payne, Thornburgh’s second in command, had only just narrowly escaped death himself from a bullet wound to his left side and shoulder. Payne’s and Lawson’s companies won the race back to the wagons.

The fate of the expedition hung precariously balanced for the next six hours. Some battle survivors and historians believe that if the Utes had coordinated a disciplined, full-strength attack on the partially encircled wagons and disorganized troopers, the battle would have been short and favored the Indians. The Utes missed the opportunity. The command saved itself by discipline, training and raw courage.

The cavalry troopers dismounted on the run and blazed away from inside a three-quarter sided circle of wagons. On the fourth side, a steep, insurmountable embankment dropped precipitously more than 20 feet down to Milk Creek. Teamsters unharnessed horses and mules that then became the Utes’ primary targets. Ultimately, more than 300 draft animals and cavalry horses would be killed, most of them during the first six hours of the battle. That by itself doomed Ute Chief Colorow’s myopic plan to halt the expedition by ambush, drive the troops back to Fort Fred Steele and force a negotiated peace that would eliminate the hated Meeker. The defenders—under the cool, calculating orders of their veteran officers, amid the chaos of wounded and

dying animals—managed to unload the wagons, build breastworks and distribute ammunition.

Frustrated and desperate, the Utes torched the tinder dry grass and sage south of the wagons. A southwesterly wind whipped the blaze toward the corral, followed by a human wave of attackers. Troopers fired blindly into the flames and smoke, while Capt. Lawson led others over the ramparts to beat down the flames with blankets, jackets and shovels. Even so, some of the wagons got set on fire; the troops were able to smother the flames and hold their position.

At the north end, Capt. Payne, using the same wind, set fire to the grass outside the corral. He intended to deprive the Indians of cover in their attempt to completely surround the barricade; he also wanted to burn a group of civilian wagons, 50 yards behind, so their contents would not fall into Ute hands. He succeeded. The Indians moved into cover on the hill above the road.

Evening cooled the exchange of bullets. Troopers traded their carbines for shovels to bury the dead and dig hospital trenches for the wounded. Dead and dying horses and mules, already causing a slaughterhouse stench, littered the ground in and around the wagons. Before sunset, cold rations were distributed. Payne banned fires, lanterns and candles. Four men volunteered to ride for help that evening, so as to take advantage of an expected midnight full moon on September 30.

Scout Joe Rankin rode practically nonstop to Rawlins the night of September 29; all day and night on September 30 and until about 1:00 a.m. on October 1—a total distance of more than 140 miles. General Crook received the rescue plea at Omaha Barracks at approximately 2:25 in the morning.

Another message reached 9th Cavalry D Company Capt. Francis Dodge, who left behind supply wagons containing food, medicine and ammunition and rode south nonstop, arriving at the battle site on October 2, unopposed. The appearance of his 30-some Buffalo Soldiers had little military impact except to boost morale. By dark, most of Dodge’s horses lay beside their predecessors.

Lieutenant-Gen. Phil Sheridan received Rankin’s telegram and, on October 1, dispatched Crook’s orders to send a relief command under Gen. Wesley Merritt. Within an hour, Merritt, commanding Fort D.A. Russell near Cheyenne, assembled troops and supplies, commandeered railroad transportation and had a plan of attack. What had taken Thornburgh a week to accomplish, Merritt achieved in several hours. He force marched his 530 troops 160 miles from four a.m. on October 2 to 5:30 a.m. on March 5 without losing one man or animal, a feat of tactical organization taught at West Point for decades afterward.

Chief Jack, even before Dodge’s company arrived, had begun telling his warriors that they were free to leave without shame. Colorow vacillated between pugnacity, complacency and resignation. The arrival of an Ute messenger from Chief Ouray, carrying an order of cessation, forestalled further debate. Waving a flag of truce, he rode out to meet Merritt. The hurly-burly now done; the battle lost and won.

Nonetheless, monumental problems remained. Foremost: The rescue of three white women and two children, the only survivors of the Meeker Massacre. Second, the capture of the Ute Leaders thought responsible for the murders of 11 male civilian employees at the White River Agency and for the ambush of the White River Expedition.

Assisted by Chief Ouray at Los Pinos Agency, on October 21, former Ute agent Charles Adams persuaded the Utes to release the Meeker captives. Adams met with the Utes to hear their side of the story and then reported to the government: “My conclusions of the whole affair are, that if Major Thornburgh had gone to the agency with escort simply, the whole trouble would have been averted; that the party of young men under Jack went out to fight unknown to the older chiefs, and that the loss of so many young men excited the others so that the killing at the agency could not be averted…. I am satisfied that the attack on Thornburgh was premeditated, and that the leaders should be punished.”

In the meantime, newspapers pandered to their readers’ lascivious speculations about the fates of the captives (both Josephine and her mother claimed their Ute captors coerced them into having sex) and fueled simmering anti-Ute sentiment into a blaze. Yet Josephine rose above the scandal mongering, sharing her experience, numerous times, in a lecture that was described as “highly picturesque and interesting.” Her life was cut short, as she lived only three years after the battle, dying at the age of 25 of a pulmonary infection. Her mother, who had been taken captive with her, wrote the following inscription on Josephine’s tombstone: “Brave daughter who with me escaped foul death while captive in thy noble father slayers’ hands. A stealthier foe has filched thy sweet young breath while lonely here I watch life’s failing sands.”

Some researchers claim that proportionately more soldiers received the Medal of Honor at Milk Creek, with 11 out of the 175 being awarded, than at any other single battle in the history of the United States. Congress did award more commendations for bravery at Milk Creek, handing out at least 30, than in any other battle of the Indian Wars. Thirteen Army troopers and civilians died, while 44 received wounds. Chief Jack estimated about equal numbers of Ute casualties for his estimated 300-400 warriors.

Two hearings, one at the Los Pinos Agency and one at the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C., unsuccessfully endeavored to assign guilt for both the Meeker Massacre and the Milk Creek Battle. The committees deemed the Milk Creek battle as a minor conflict between two independent nations. The Meeker Massacre occurred on federal land, therefore Colorado’s criminal statutes did not apply.

The Milk Creek Battle and Meeker Massacre ultimately provided the politicians, mining companies and land speculators with the excuses they needed to void the 1873 Brunot Treaty, which had passed most of the San Juan Mountains into the government’s hands; but with miners filling up the San Juan, settlers began to covet areas north of the mining region that had been granted to the Utes in the treaty. By September 1881, a year after Ute Chief Ouray’s death at age 47, all Colorado Utes had been forcibly evicted into Utah. Today, they occupy the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute reservations along the Colorado and New Mexico border.

Richard Davis is a third-generation Coloradan whose grandfather homesteaded in the territory. He has an MA from Colorado State University in political science.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Denver Public Library, Western History Collection, unless otherwise noted –

– By Jeffrey Beall / Auraria Library, University of Colorado in Denver –