On this summer month, when most Civil War minds think about the events 150 years ago at a town called Gettysburg, I’d like to draw your attention to a great American, and a Southerner to boot.

On this summer month, when most Civil War minds think about the events 150 years ago at a town called Gettysburg, I’d like to draw your attention to a great American, and a Southerner to boot.

Sam Houston died 150 years ago, hated by practically every Confederate in the state he had helped forge and bring into the Union, and loved with all his heart.

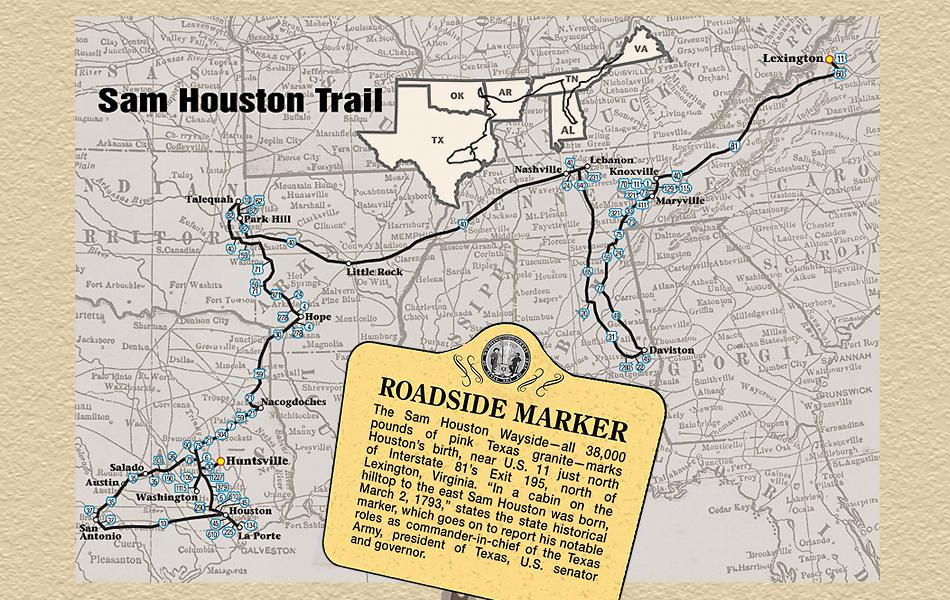

He was born in Virginia, lived in Tennessee and became a legend in Texas. He served as a U.S. senator from Texas, congressman from Tennessee, governor of Tennessee and Texas, two-time president of the Republic of Texas and defender of Indian rights. My favorite image of Sam, though, is when Texas secessionists called the governor to come and take the oath of the Confederacy.

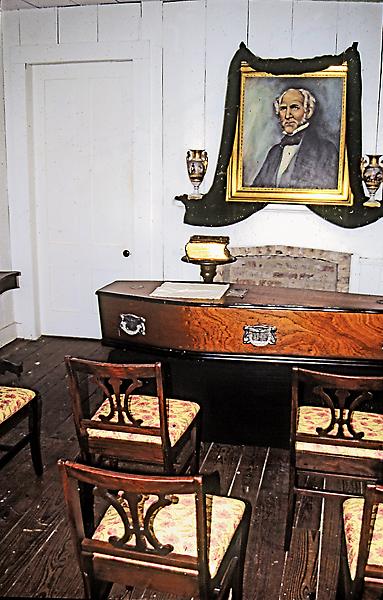

Big Sam just sat in his chair in the capitol’s basement … whittling.

That took guts. But Sam always had a lot of guts.

The Legend Begins

He was born in 1793 at Timber Ridge in Rockbridge County, Virginia, which certainly doesn’t overlook the state’s Houston tribute. The wayside monument is just off Interstate 81.

These days, Timber Ridge is all about promoting the Civil War—with good reason, since 1993’s Sommersby and 2003’s Gods and Generals were filmed here. In fantastic Lexington, you will find the Museum of Military Memorabilia, the Stonewall Jackson House, the Virginia Military Institute Museum and the burial sites of Robert E. Lee (Lee Chapel and Museum) and Stonewall Jackson (Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery).

In his early teens, Sam moved with his family to Blount County, Tennessee, after his father’s death. Farming and clerking didn’t interest him, so he ran away from home, living for a while with the Cherokees, who named him “Colonneh,” which means Raven.

“His family’s loss, certainly, was history’s gain,” biographer James L. Haley writes.

Yep, and you can find a lot of that history in East Tennessee, at the East Tennessee Historical Society in downtown Knoxville and at the Sam Houston Schoolhouse in Maryville. By 1812, Sam had returned to the white settlements. His one-room schoolhouse was the first school built in the state; Maryville’s replica log structure stands on the original site.

He didn’t teach school for long. The War of 1812 started, so Sam joined an infantry regiment and marched south into Alabama under the command of a fellow named Andrew Jackson.

To follow his trail, you should head south to Horseshoe Bend, roughly 75 miles northwest of Montgomery. In a battle against Creek Indians in March 1814, Sam made a big impression on Old Hickory himself. Despite being wounded in the groin by a Creek arrow, Sam kept fighting, only to get wounded again in the shoulder and arm.

Like I said. Guts.

The military park in Daviston, one of only five National Park Service parks dedicated to the War of 1812, includes a visitor center, a three-mile road tour and a 2.8-mile nature trail. You may find occasional demonstrations representing Creek and militia programs but, as the park rangers point out, this is a solemn place. An estimated 550 (some accounts state more than 800) Creeks died in the battle, as did almost 50 white soldiers.

Up in Tennessee

Recovering from his wounds (the shoulder wound never completely healed), Sam wound up in Nashville, so it’s time to head to Music City U.S.A.

But first, detour east of Nashville to Lebanon, where Sam practiced law for 10 months after studying in Nashville. His office, a restored log cabin, is part of Fiddlers Grove Historical Village.

In Nashville, you’ll find a museum dedicated to Country music stars, but on this trip, the two must stops are the Tennessee State Museum and Jackson’s home, the Hermitage.

The state museum includes permanent exhibits and a hall of changing exhibits. For Sam buffs, the permanent “Frontier” and “The Age of Jackson” exhibits are must-see. (Of course, the whole museum is must-see, and it’s free!) But for you Civil War buffs, “The Civil War and Reconstruction” is part of the permanent collection, while “Discovering the Civil War,” a temporary exhibit from the National Archives, runs through September 1.

The Hermitage, completed in 1836 during Jackson’s second term as president, showcases original art, wallpaper and furniture. Outside the home, you will find the tomb of Andy and his wife. On June 8, 1845, Sam arrived at Hermitage just an hour after Jackson’s death. The Hermitage is worth the admission unless, maybe, you’re Cherokee. Jackson was, after all, partly responsible for the Trail of Tears.

In 1818, Sam was elected attorney general for the Nashville district, and, as one of Jackson’s protégés (David Crockett was another), his political career skyrocketed. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1823 and as governor of Tennessee in 1827 at age 34.

Then came scandal.

On January 22, 1829, Sam married 19-year-old Eliza Allen of Gallatin, but his new bride returned to her folks 11 weeks later. The marriage ended (though the divorce wouldn’t be finalized until 1837). Sam resigned as governor in April, and he headed west.

The Dark Years

Head west, yourself, toward Oklahoma, stopping in Little Rock, Arkansas, to visit the fabulous Historic Arkansas Museum.

Sam returned to the Cherokees. He married a mixed-blood Cherokee, was granted Cherokee citizenship and operated a trading post called Wigwam Neosho near Fort Gibson. During this three-year exile, Cherokees gave Colonneh a new nickname: Big Drunk.

The best places to learn about the Cherokees are in Tahlequah, the Western branch’s capital, where you should check out the Murrell Home and Cherokee National Supreme Court Museum. Another great place is the Cherokee Heritage Center, in nearby Park Hill. The center’s Tsa-La-Gi Ancient Village has been a worthwhile stop, and will be even more so after the June 3 grand opening of the village, which will now be called Diligwa. This change marks the site’s advancement in sharing the history beyond European contact days (when it was Tsa-La-Gi) to Cherokee life in the early 18th century.

Sam eventually left his Cherokee wife and returned east, whipping Representative William Stanbery of Ohio with a cane on the streets of Washington, D.C., on April 13, 1832. Stanbery, Houston thought, had insulted him over an Indian rations contract. Big Sam was back, getting off with a fine and reprimand.

Like Davy Crockett, Sam left politics and Tennessee and headed to Texas.

We are leaving, too, but everyone who was anyone stopped at Washington, Arkansas, founded in 1824 on George Washington’s birthday, on his or her way to Texas. Sam did. So did Crockett. So did James Bowie. Historic Washington State Park re-creates life in the Arkansas frontier with about 30 restored buildings.

Texas Hero

On December 2, 1832, Sam entered Texas, settling in Nacogdoches, where he set up a law practice and served as a delegate in San Felipe at the Convention of 1833. Things were getting hot in Texas. By October 1835, Sam believed the Texans and Mexicans faced inevitable war. On November 12, Sam was appointed major general of the Texas army.

Nacogdoches, Texas’s oldest town, is a great place for history buffs. You should include these stops on your trip: Stone Fort (which never was a fort) at Stephen F. Austin State University; Sterne-Hoya Museum, a circa 1830 home; Millard’s Crossing Historic Village, a reconstructed early 1800s village; and Durst-Taylor Historic House and Gardens, another home that interprets life from 1840-60.

But revolution forced Sam to leave Nacogdoches, so head south, stopping at Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site, home of the Star of the Republic Museum, Independence Hall and Barrington Living History Farm. The Alamo gets all the glory, but delegates here risked their lives by signing the Texas Declaration of Independence on March 2, 1836. Said Sam: “Independence is declared; it must be maintained.”

That was his job. He won that independence at San Jacinto.

On April 21, 1836, Sam led his ragtag Texas army against Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s Mexican troops. The San Jacinto affair was more of a slaughter than a battle, as Texians were upset about the slaughter of their friends at the Alamo and Goliad. Houston was wounded in the ankle, but Santa Anna was captured, and Texas became an independent republic. The story is well-preserved at the 1,200-acre San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site, near sprawling Houston, which was founded in 1836.

In Austin’s City Limits

Once again, Sam was a hero. He took over as president of the Republic of Texas on October 22, 1836, so let’s head to Austin for this stage of his life.

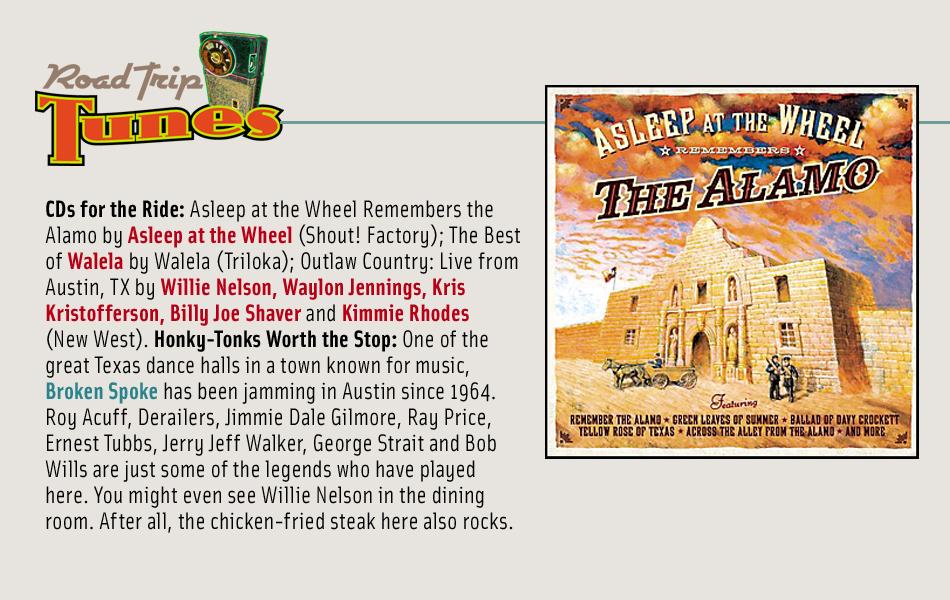

All right. San Antonio, first. Anybody visiting Texas should go to the Alamo, even if Houston told Jim Bowie to remove the cannons, blow up the Alamo and take his command to Gonzales.

But Austin is more Sam Houston than San Antonio. The Bullock Texas State History Museum is bold and big like Texas (and Sam). Sam served again as president of the Republic, then helped Texas become a state. In 1840, he married Margaret Moffette Lea in Marion, Alabama, and his Baptist wife curbed Sam’s drinking. Austin is where Sam defied the fire-breathers at the 1861 secession convention and, ever loyal to the Union, left Austin for his home in Huntsville.

The Last Years

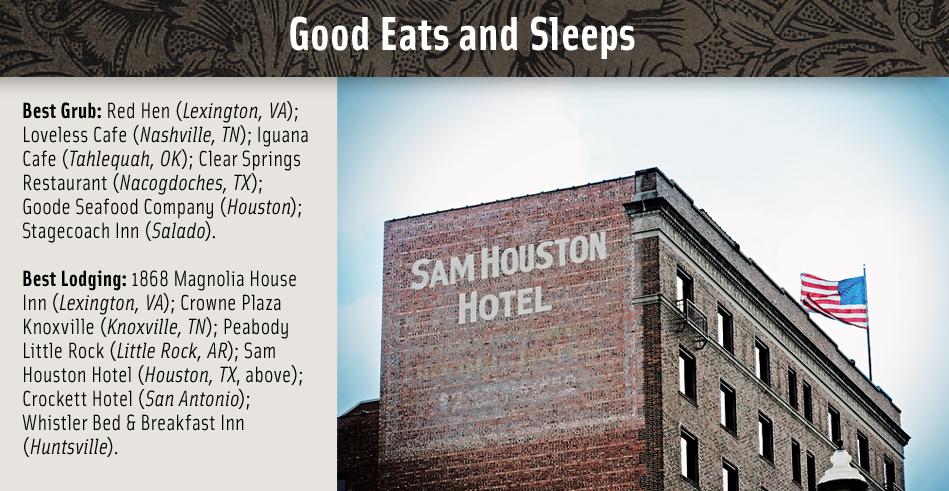

On your way to Huntsville, you should be sure to stop at the Stagecoach Inn in Salado. Still taking in guests today (and making tasty food), the inn is where, in 1861, Sam gave an anti-secession speech from the balcony, where, Sue Flanagan writes in Sam Houston’s Texas, “his audience had all the warmth of a norther.”

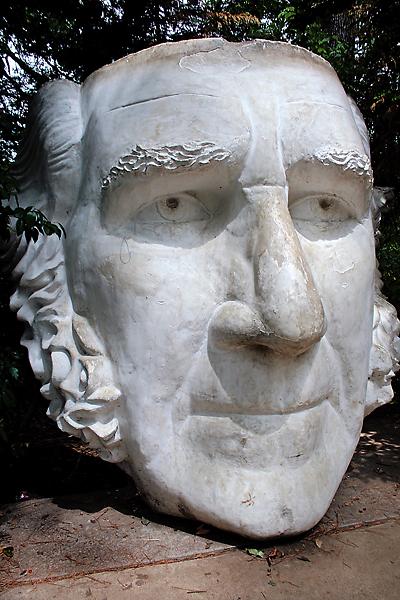

He felt much more welcome in Huntsville, having called it home since the 1840s. Huntsville still honors Sam, including A Tribute to Courage, sculptor David Adickes’s 67-foot statue of Sam that was dedicated in 1994.

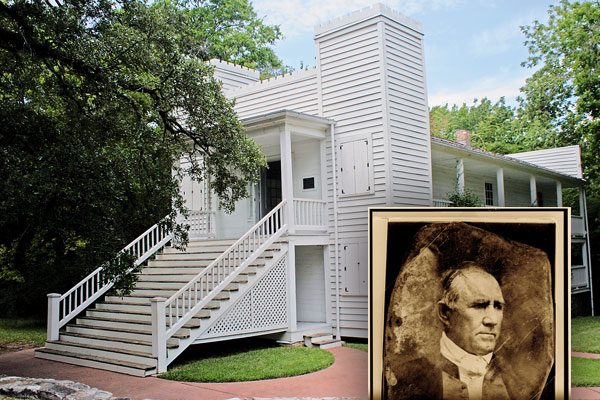

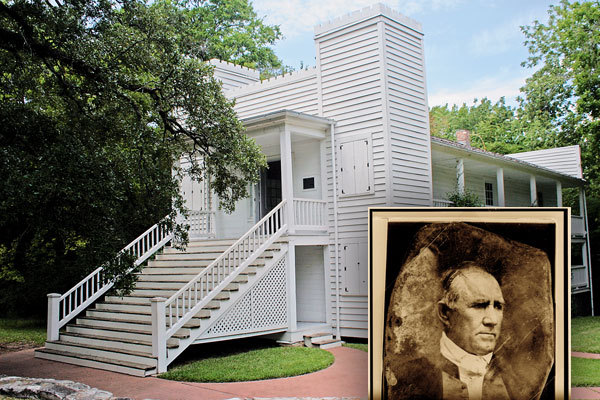

The Sam Houston Memorial Museum features not only a great museum, but also the restored Woodland home, where Sam lived from 1847-59; his law office; the Steamboat House, where the Houstons moved in 1862; and other buildings.

The Steamboat House is where Sam died of pneumonia on July 26, 1863. His last words, said to his wife, were, “Texas! Texas!” He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery. Jackson’s words are recorded on the marble monument: “The world will take care of Houston’s fame.”

But I think the best testament to Sam was the one word found inscribed in a gold ring he had worn on his left pinky. Margaret removed the ring and showed it to her children. On the inside was a one-word inscription: Honor.

Johnny D. Boggs recommends reading James L. Haley’s Sam Houston, avoiding rush hour on the San Antonio-Austin I-35 corridor and never watching The First Texan starring Joel McCrea.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –