A Chinese man enters a barn followed by Doc Cochran and Johnny Burns, a thug working for the infamous saloon owner, Al Swearengen.

A Chinese man enters a barn followed by Doc Cochran and Johnny Burns, a thug working for the infamous saloon owner, Al Swearengen.

The Chinese man carries a body slung over his shoulder. As he reaches a hog pen, he tosses the body over the fence and into the mud. Ravenous hogs rush to the body and begin to tear it apart. “That’s Mr. Wu,” says David Milch, the Executive Producer of HBO’s hit series Deadwood, during his commentary on Episode 1, “I love this guy.”

Deadwood is a gritty, captivating show. The series portrays its Chinese characters as mysterious, hardworking, lower class people. But were the Chinese of the real Deadwood like those depicted on TV?

I traveled to Deadwood in the Black Hills of South Dakota to find out who these Chinese of Deadwood really were. Jerry Bryant, research curator and resident archaeologist at Deadwood’s Adams Museum, invited me to his office. I explained my mission and then asked, “Jerry, what are the similarities between the Chinese of the historic Deadwood and the HBO series?”

“None,” he shot back. “For instance, the TV show has Chinatown off to the side of Main Street when in reality, Chinatown, or as the residents of Deadwood called it, the Badlands, was actually a part of Main Street. Deadwood is a long skinny town at the bottom of a gulch with hardly any room for side streets. As you enter Deadwood Gulch from the north you pass through Elizabethtown, then the Badlands, then into Deadwood.”

“And another thing,” Jerry added. “There were never any Chinese prostitutes kept in cages. The good citizens of Deadwood would never have put up with that.”

For the next hour, Jerry gave me a rapid lesson on Deadwood, the Chinese, what to read, where to research and who to contact on Chinese frontier history.

“Okay, one last thing I’ve got to ask,” I said toward the end of my interview. “Did the Chinese really feed human bodies to the hogs in Deadwood?”

“Never happened,” he answered, with a chuckle.

The first two seasons of HBO’s Deadwood portrayed the Chinese as rough, hardworking, shadowy underworld characters. But is this portrayal really true? Milch states on HBO’s Deadwood website, “I want to make it clear that I’ve had my ass bored off by many things that are historically accurate.”

So who were Deadwood’s Chinese? Where did they come from? What goals did they have? What lives did they lead? And what happened to them? Jerry gave me several good leads to begin my search for the real Chinese inhabitants of Deadwood that revealed a story far richer than what viewers can extract from TV.

The Real Deal

During the mid-1800s, China’s southern Guangdong province was in turmoil. Guangdong along with its capital, Canton, was a hothouse of rebellion against the Manchu dynasty, which, 200 years earlier, had invaded China from Manchuria, conquered the nation and replaced the Ming dynasty. Famine and the destruction of crops during periodic rebellion against the government resulted in the deaths of millions of people.

The addictive opium was also wrecking thousands of Chinese lives. British traders smuggled opium into China. When the Chinese government tried to enforce an embargo on opium shipments, the British government attacked, forcing the Chinese to consent to the trade. In 1847, British banks cut off funding to businesses in Guangdong for over a year, throwing 100,000 men out of work. Desperate husbands, fathers and sons grasped at the rumors of Gum Shan—Gold Mountain.

James Marshall found gold at Sutter’s Mill in California in 1848. A Chinese man living there wrote to a friend in Canton about the discovery. Soon everyone in Guangdong was talking about Gum Shan, where a person could pick up gold nuggets off the ground. The Chinese gold rush was on.

The men’s plan was to find enough gold in Gum Shan so that the family back home in Guangdong could live comfortably. Once the Chinese prospector achieved this goal, he would return to live in luxury in China.

But when the Chinese came to the goldfields, the Chinese miners were so efficient at mining that their white neighbors became jealous and began restricting the mining rights of the Chinese.

Some of these miners shifted gears and found jobs with the Central Pacific Railroad, which was building the transcontinental railroad from the west. Central Pacific recognized that the Chinese worked faster, cheaper and better than the white workers did. It was their expertise in explosives and working on cliffs that made building the railroad less costly. On May 10, 1869, when the railways were joined from east and west to create the transcontinental railroad, the Chinese were out of a job.

Chinese prospectors and business-men spread throughout the West. Wherever there was a new strike, the Chinese made their way to that mining district—California, Arizona, Nevada, Montana, Idaho, Washington and Colorado. The predominantly white population developed prejudices against the Chinese based on their different language, work ethic, dress and culture—all causing friction. To lessen hard feelings against them, the Chinese began to work old placer mines that whites believed were useless. They also opened businesses that held little conflict with whites, such as restaurants, laundries and stores carrying Asian goods. Most Chinese lived the American dream—they were independent businessmen.

Paha Sapa Gold

By 1874, prospectors had explored all of the continental U.S. for mineral deposits—all that is except one area, which lay within the Great Sioux Reservation; Paha Sapa in the Lakota language, Black Hills in English.

Lieutenant Col. George Armstrong Custer led an expedition through the Black Hills in 1874. The expedition’s geologists reported to Congress the positive prospects for gold and other minerals, triggering an illegal gold rush to the Black Hills.

At first, the government tried to round up and evict the trespassers but soon gave up its attempts and embarked on a course to buy the land from the Lakota people. Meanwhile, streams of miners poured into the Black Hills. In the fall of 1875, prospectors entering Deadwood Gulch in the northern Black Hills discovered gold along Whitewood Creek. Miners started to lay claims; but the real rush for gold did not start until the spring of 1876.

Chinese prospectors were not far behind the first discoverers of gold in Deadwood Gulch. One early arrival was Fee Lee Wong.

Wong and his brother had left Guangdong, finding jobs as laborers in Gum Shan. In 1870, 24-year-old Fee Lee and his brother arrived in California.

With news of gold in the Black Hills, Fee Lee took a job as a cook with a small party of white prospectors headed for the Hills. Along with the usual hardships of the trail, the party fought off attackers. When the prospectors reached Deadwood in 1876, they staked claims and divided them by lot among the group. One of the members wanted to exclude Fee Lee, but the others overruled him and Fee Lee received two claims. Gold was soon discovered on the claim next to Fee Lee’s claims. He may have sold his claims for as much as $75,000, but there is no record of the property transaction. Deadwood’s fires destroyed many of the early records. Fee Lee’s story is one of the more fortunate ones.

Most Chinese headed to Deadwood via train to Cheyenne, Wyoming, or Sidney, Nebraska. From these railheads, they rode a stagecoach 300 miles to Deadwood or traveled alone or in small groups. Some followed the Missouri River from the Montana and Idaho goldfields to Bismarck or Fort Pierre, Dakota Territory, and then crossed the prairie to the Black Hills.

Just as Fee Lee did, some Chinese acquired placer mining claims. As time went on, most of the claims were worked over. The mining turned to hard rock, requiring lots of capital and manpower. Most of the Chinese did not have the money to invest in equipment and people to perform that intensive type of mining. But they still bought old placer claims to rework them and extract more gold.

Opportunists

Another successful way that they made money was by opening a laundry service. Think about it—a large population of young, dirty, hungry miners with excess cash (or gold dust). These men did not waste their time cleaning their clothes and cooking their food; they were in Deadwood to find gold.

The Chinese laundry operators were pretty clever. They saved the wash water from the miners’ clothes and sluiced it, recovering gold dust—in other words, mining the miners. Half the recorded Chinese population in Lawrence County, of which Deadwood was the county seat, were involved in the laundry business, according to the 1880 U.S. Census.

The number of Chinese who owned restaurants was greater than those owned by Caucasians. The 1898 Black Hills Residence and Business Directory listed 11 restaurants in Deadwood, seven of which were Chinese-owned. The Chinese learned to cook what American prospectors wanted to eat—for the most part, steak, potatoes and other standard fare. Wong Kee, the owner of the Bodega Café, had a standing joke with his patrons. “What kind of pie do you want?” he’d ask. The diner would name his favorite pie. Wong would then laugh and say, “We have apple.”

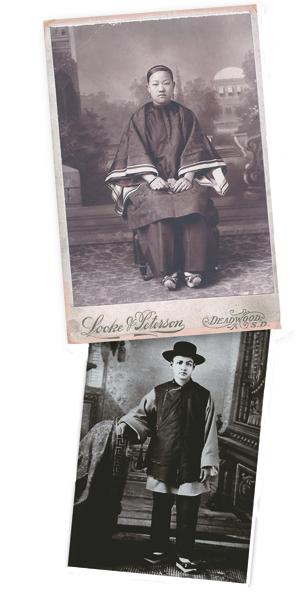

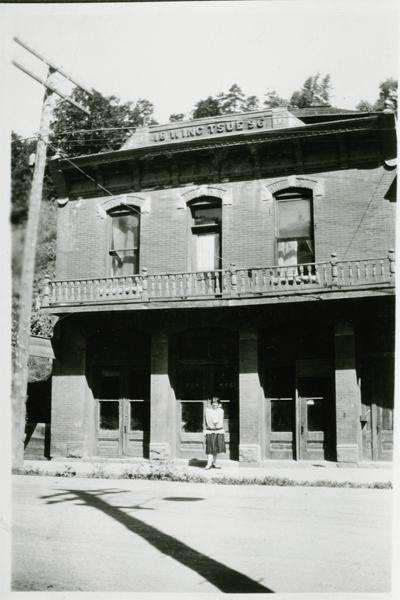

Fee Lee Wong used his profits from his mining claim to open the Wing Tsue Emporium on Deadwood’s Main Street. Wing Tsue is Cantonese for Assembly of Glories. Fee Lee spoke English well and was respected by and socialized with the non-Chinese community.

His advertisement in the 1898 directory reads: “Wing Tsue, Dealer in Chinese Groceries and Provisions. Chinaware and Japanese Goods, Silk Handkerchiefs, Silks and Dry Goods of all Kinds. Fireworks, Chinese Curios, Novelties, Etc., Etc. I also carry a full line of Chinese Medicines, Chinese shoes and Clothing. Americans as well as Chinese are invited to call and Inspect my goods.”

The Chinese were employed in a wide variety of positions including house servants, private cooks, barbers, physicians, lumberjacks, prostitutes and gamblers. They owned real estate, including hotels and opium dens. Some Chinese even became cowboys. A “Chinese cowboy” was “seen on the street yesterday. He was rigged out with leather pantalets, belt, cartridges and gun,” reported the 1895 Black Hills Daily Times.

An accurate count of the Chinese population of Deadwood is hard to determine. The 1880 census recorded 221 Chinese in Lawrence County, with 110 of them living in Deadwood. But some researchers think this figure is an underestimation because the Chinese distrusted the government. The census takers probably only counted those who owned property, ran businesses or were employed by whites. Other facts recorded by the census reveal 202 Chinese males and 19 females, mainly between the ages of 18 and 45. So there was a large population of single Chinese men.

These men had even less of a hope of finding a good spouse when Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. The act cut off almost all new immigration to the U.S. from China. The Chinese population of Deadwood became stagnant as the men became older and were unable to send for their wives or marry within their race. Fee Lee Wong was one of the lucky ones. He brought his wife to Deadwood in 1884 before amendments tightened provisions in the original law.

White Pigeon Ticket

Cut off from traditional family and female companionship, the young Chinese males of Deadwood enjoyed many of

the same pastimes as their white neighbors, including a good drink, camaraderie—male and female—and most of all, gambling.

Mark Twain quipped about the Chinese, “About every third Chinaman runs a lottery.” The Chinese bet on everything. Some of their favorite betting games included poker, fan-tan and white pigeon ticket, also known as the Chinese Lottery. The Chinese Lottery was popular with whites. They bought tickets, even though they couldn’t identify the Chinese characters. Apparently, any bad feelings some whites may have had toward the Chinese didn’t extend to gambling; they believed the Chinese would give them the correct winnings. The Chinese Lottery eventually evolved into the game of keno.

Legal Opium Dens

The Chinese enjoyed a drink of rice wine and the standard alcoholic drinks consumed by many of Deadwood’s residents. A number of Chinese also used opium, which was legal to sell and use in Deadwood during the early years. Opium den owners bought a license from the city, the same as saloon owners. Most Chinese smoked opium for med-icinal purposes or pleasure. Deadwood’s non-Chinese residents who ventured into the opium dens came to experiment with the drug.

Soon enough, the Black Hills Daily Times editor sounded an alarm for these opium dens in a February 11, 1882, issue: “The attention of city authorities is called to the opium joints now being conducted wide open in that portion of the city known as Chinatown. Where white people, and black ones too, hit the pipes as often as they can raise 50 cents. Owing to the fact that none of the old joints have been molested for some time, several new ones have started up, where can be seen at almost anytime of the day or night, forms of men and women stretched out perfectly unconscious of their surroundings, reveling in the pleasant dreams that the devilish narcotic brings to them for a brief one hour. If the evil cannot be suppressed a restriction can at least be put upon it that will prevent its further spread.” Congress finally outlawed opium use in 1909.

Fun and Games

Fire was always a major concern in Deadwood. Fee Lee Wong’s store was the source of a fire in 1885 that damaged other buildings in Chinatown. The Chinese organized two fire hose teams. Each team consisted of 10 men pulling a two-wheeled cart with fire hoses.

The teams marched in Deadwood’s July 4, 1888, parade, dressed in traditional and Western clothing, carrying banners and flags, and accompanied by a band playing Chinese music. The mostly white crowd clapped and cheered as they passed down Main Street. After the parade, the two teams held a race for the “fastest Chinese hose team in the world.” The contestants lined up on Main Street, but before “go” could be shouted, someone tossed an exploding firecracker and the race was on. Fee Lee’s team was well out in front; but one of the men stumbled and fell. Hi Kee’s team won the race—200 yards in 30 seconds. No one knew of any other Chinese fire hose teams, so the citizens of Deadwood declared Hi Kee’s team the Champion Chinese Hose Team of the World. No one, to date, has ever contested the claim.

The Chinese participated in American holidays like 4th of July and Christmas, but they went all out for their own celebrations, the most spectacular holiday being the Chinese New Year. It’s usually celebrated in February, with the start of the new moon, and lasts 15 days. The Chinese prepared weeks in advance for the New Year. During the celebration, they closed their shops and took a vacation from work. They decorated their houses with banners, paintings and lanterns. They shot off fireworks and firecrackers day and night. The Chinese marched in parades accompanied by their bands. They paid off all their debts, invited one and all to visit their homes, and gave the visitors gifts.

Joss House to Tongs

The Chinese built a Joss House, or temple, on Deadwood’s Main Street, where they conducted Buddhist and other Chinese religious ceremonies. The Joss House also served as a meetinghouse.

Some Chinese became Christians through the efforts of Deadwood’s Congregational and Baptist Churches. The members of these churches conducted night schools for the Chinese to learn how to speak, read and write English.

Mayor Sol Starr and Dr. Henrich Wedelstaedt, both prominent Deadwood citizens and members of the city’s Masonic Lodge, worked with the Chinese to establish a “Chinese Masonic Lodge.” This lodge was never part of Freemasonry. The Chinese allowed only Mayor Starr and Dr. Wedelstaedt to attend their lodge functions. The Chinese Masonic Lodge was a prominent organization, and the Deadwood newspapers often mentioned Chinese masons. It may actually have been a Chinese tong.

There were possibly two tongs in Deadwood. Tongs were important social societies that provided their members fellowship, recreation and social services. Sometimes tongs engaged in criminal activities. No evidence has been found to show that Deadwood’s tongs had a criminal element, but the hatchet was the weapon of choice for tong members and it was sometimes wielded in local attacks.

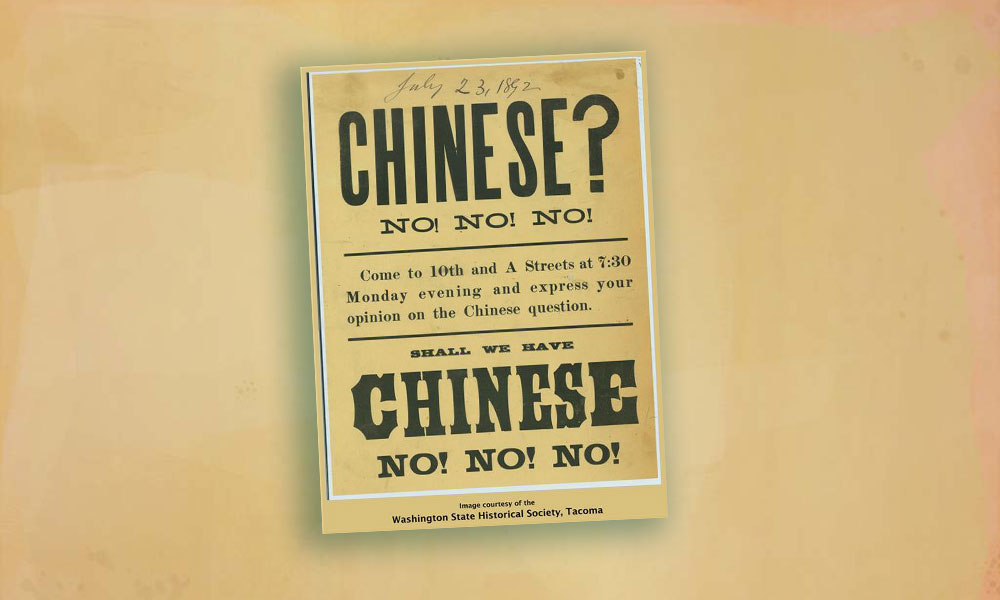

But the Chinese may have had good reason to strike out. White mobs were known to loot and burn Chinese homes. In 1878, a short-lived anti-Chinese organization, the Caucasian League and Miners Union, emerged in the northern Black Hills. Its mission was “to protect the interest of white miners.” During the league’s short existence, assailants burned down four Chinese houses and attempted to blow up another house. Kuong Wing, one of Deadwood’s Chinese leaders, printed a general letter in the paper to assure the white population that the Chinese wanted to be good neighbors and not take their jobs. Through this published assurance and the goodwill efforts of friends of the Chinese community—Mayor Sol Starr, Judge Granville Bennett and others—the Caucasian League faded away.

As time went on, the Chinese and non-Chinese of Deadwood learned to tolerate, if not enjoy, each other’s company. Whites even came to the assistance of their fellow citizen, Fee Lee, who had traveled to China for a visit. On his return to the U.S., the Immigration Office detained Fee Lee in Port Townsend, Washington. Some of Deadwood’s citizens learned of Fee Lee’s plight and contacted the Immigration Office. He was allowed to return home.

But still, Deadwood was a rough town, and the Chinese were also victims of murder and crime. At times, Chinese fought each other. Tong Hay and Ton Lem Sang attacked Ching Kee Lang with hatchets. The police arrested them, and a lucky Ching Kee Lang recovered from his wounds.

One of the most notorious unsolved crimes in Deadwood was the brutal murder of Di Gee, the China Doll. Di Gee was one of the first Chinese to arrive in Deadwood in 1876. She was young, beautiful and rich, and she owned three well-furnished houses on Main Street. Outside the Chinese community, no one knew how the unmarried woman made her living. Single Chinese women were almost always either prostitutes or servants, but there is no evidence that Di Gee was either of these.

On November 27, 1877, two people murdered Di Gee. One attacker smashed her in the face with a hatchet, while the other stabbed her repeatedly in the back with a small knife. The coroner stated that Di Gee must have died from multiple blows to the head. The authorities determined that the attackers did not rob her.

Who murdered Di Gee? No one knows. The Chinese would not cooperate with Deadwood authorities. One thing is certain; after the murder, the people who moved into Di Gee’s house heard a knock on the door at night. Di Gee’s voice cried out, “Moo shot ngin,” meaning “Don’t kill.” Then they heard the sounds of her murder but never saw anything. The occupants soon moved out of the house, and no one would live in it. Neighbors also began hearing Di Gee’s voice and moved away.

The Chinese community held an elab-orate funeral for the China Doll and kept her burial place a secret.

Chinese funerals were usually exciting extravaganzas. The Chinese struck the gong at the Joss House to notify everyone of a death. Everyone dressed in white or brightly-colored clothing and joined a procession to take the body to the cemetery. People carried banners and lighted tapers called Joss sticks, and tossed firecrackers and colored pieces of paper. A Chinese band played cymbals and drums. Sometimes the Deadwood City Band led the procession. It was a joyous parade. Many of Deadwood’s non-Chinese residents joined the procession, as well; some out of friendship, others out of curiosity and others went for food and gifts.

Mount Moriah, Deadwood’s Boot Hill, is a steep climb from the gulch below. From on top, the people saw all of Deadwood. After burying the body in the Chinese section of the cemetery, the Chinese would pass out food and gifts to all who attended. The Chinese left food at the gravesite for the spirit of the departed to eat before starting on its journey to heaven. Children often hid themselves and waited until everyone left so they could raid the food left behind for the spirits.

One popular Deadwood legend states that a white man asked a Chinese man when the dead would come out of the graves to eat the food. “Our dead will come up to eat our food when your dead come up to smell your flowers,” he replied.

Many Chinese had provisions in their contracts with the companies that brought them to America, that if they died here, the contract companies would ship their bones back to China. After the body had been in the ground for two or three years, an undertaker or Chinese worker dug up the bones, wrapped them in newspaper or cloth, placed them in zinc-lined boxes and shipped them back to China. Some people believe most of the bodies were removed from Mount Moriah, while others believe many are still buried there.

The Last Remnant of Chinatown

Since not many Chinese formed families, thanks to the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Chinese population slowly drifted away from Deadwood, either heading back to China or to other Western towns. By the mid-20th century, Deadwood’s Chinese lived on only in the memory of those whites who had been children when the Chinese were an integral part of town life.

Although Fee Lee Wong found success in the U.S., he was still a traditionalist and returned to China with his family in 1919 so that his children could learn their Chinese heritage. Fee Lee died in China in 1921, but many of his children yearned for the U.S. and returned. In 2004, Edith Wong, Fee Lee’s great-granddaughter, organized a family reunion in Deadwood. Sixty-seven members of the Wong family arrived in Deadwood for their first family reunion and posed for a group photograph in front of the Wing Tsue building.

If you visit Deadwood today, you will find little left of the Chinese. During Deadwood’s annual Days of ’76 parade, a local girl is designated the China Doll and rides on a parade float. The Adams Museum displays Chinese photographs and artifacts for the public to view. Visitors can also drive up to Mount Moriah to view the remaining graves in the Chinese section of the cemetery.

But the last recognizable remnant of Deadwood’s Chinatown was de-stroyed just last year. On December 24, 2005, Gene Johner, the owner of Fee Lee Wong’s Wing Tsue Emporium, demolished the building, in direct violation of Deadwood’s historic pres-ervation ordinances. As of publication, the complaint filed by the City Commission was still being investigated.

The only building left in Chinatown is the Hi Kee store, now called the Deadwood Gulch Saloon, but Adams Museum’s Research Curator Jerry Bryant says it has been refurbished and bears no resemblance to its original structure. For all intents and purposes, Deadwood’s historic Chinatown is gone.

The old saying goes “Art imitates life.” Well in Deadwood, you can say, “Art imitates life—life imitates art.” The City of Deadwood has built a mockup of the HBO Deadwood set, complete with a replica of a hog lot named Wu’s Pigs.

But if you listen late at night, you just might hear the China Doll cry out, “Moo shot ngin.”

Photo Gallery

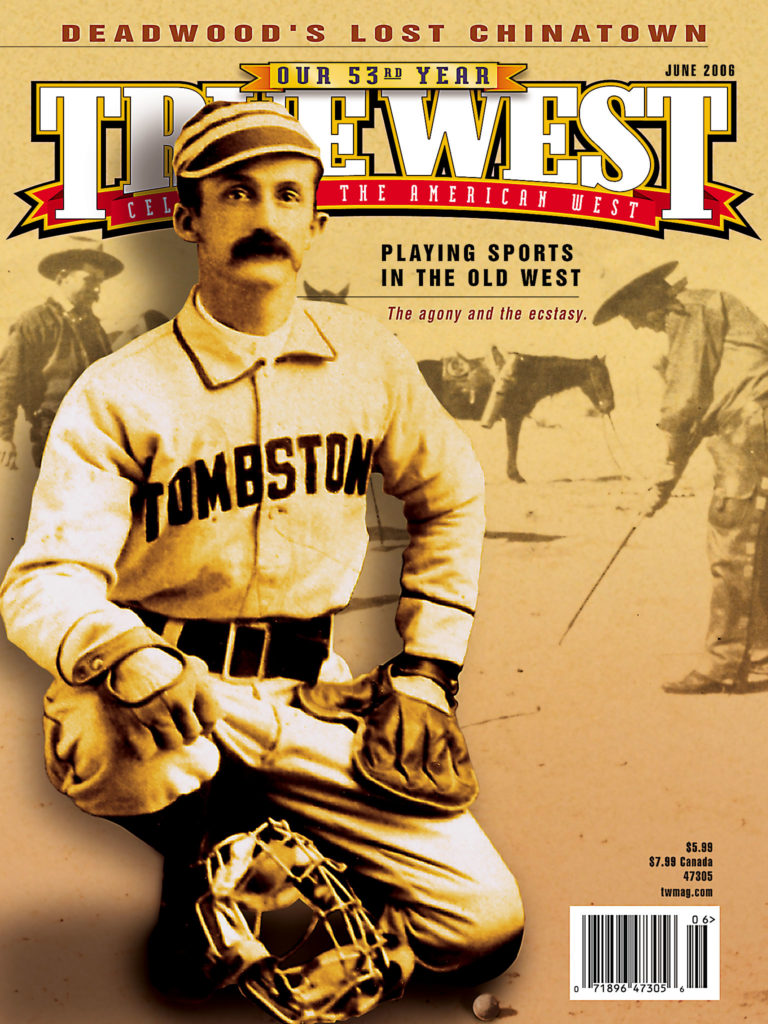

The Third Season of Deadwood will premiere on HBO this June.

– All images courtesy Adams Museum in Deadwood, South Dakota –