As blazing timbers crashed downward, destroying a once lovely adobe home and the dreams of its occupants, an era of hostility and bloodshed also came to its bitter climax.

As blazing timbers crashed downward, destroying a once lovely adobe home and the dreams of its occupants, an era of hostility and bloodshed also came to its bitter climax.

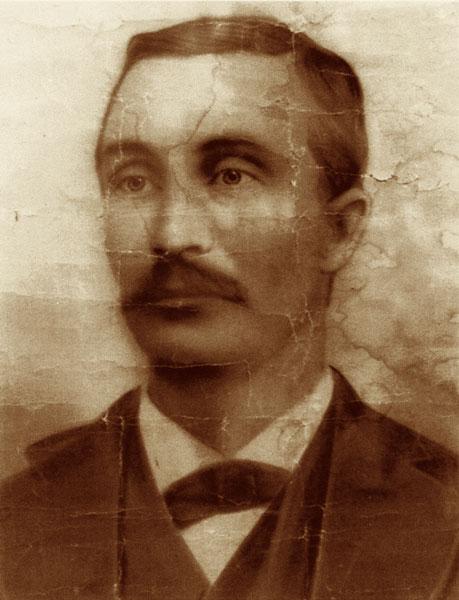

Destruction of the McSween home during a sultry July in 1878 brought to a dramatic conclusion the violent conflict between two rival factions of ranchers, businessmen and lawyers for economic control of Lincoln County, New Mexico. The educated and handsome Alexander McSween died with five bullets in his body. His widow and friends swore revenge.

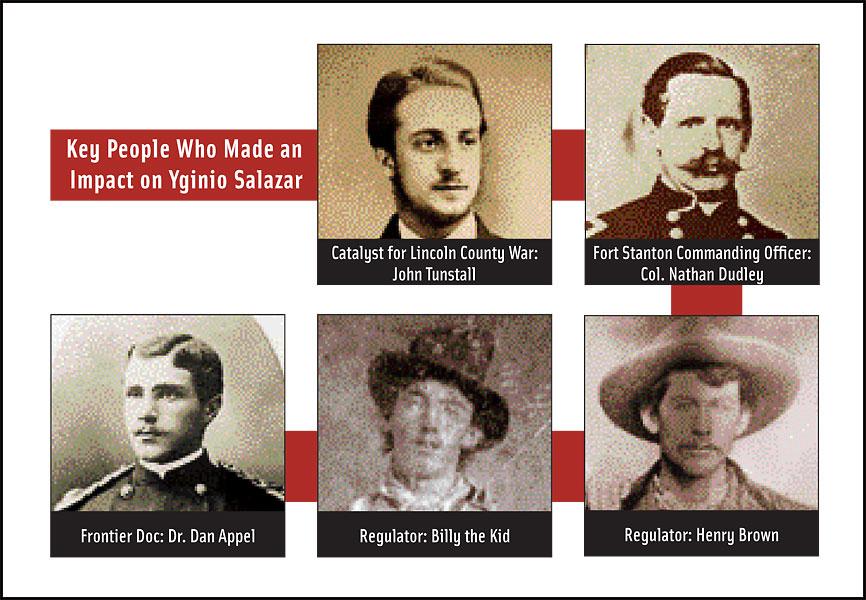

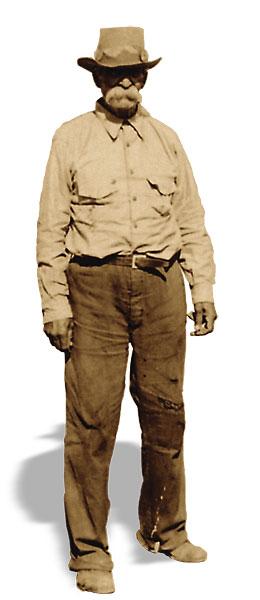

These men, Hispanic and white, were mostly young. Famed author Fred Nolan reminds us how young: “All of McSween’s fighting men were in their twenties and many, like Yginio Salazar, still in their teens. Scurlock and Bowdre were the oldest at 29. Frank Coe was 27, George Coe, 22, and Henry Brown and [Billy] the Kid both 19.”

Yet one man who had been drawn into the war was even younger than the infamous Kid. Although barely four years separated them in age, that gap was like a wide canyon in terms of maturity and past escapades. In 1878, Salazar was 15. Three years later, in July 1881, Sheriff Pat Garrett gunned down the 21-year-old Kid. Salazar was 18 and had a full life ahead of him…maybe.

Salazar was surrounded by several men older in age and deed who fought bravely, and perhaps foolishly, for a lost cause and for leaders who had already been murdered. The men who called themselves the “Regulators” were a tough band of hombres.

Salazar, like so many of la gente (the people), came from a good family of Hispanic pioneers. He reportedly played the violin, from an early age, at dances in Fort Stanton. His family had a farm in Lincoln. His life could have followed the same path as the Kid’s. Events just “happened,” and before you knew it your family was drawing its line in the sand and stepping over to fight for one side or the other.

The turning point had been the murder of rancher John Tunstall. Then a bloody battle ended at the elegant McSween home. The raging fire that consumed the home left but one room for the men to pray for the calm of darkness so they could escape out the back to the Rio Bonito. With lungs full of smoke, the men must have seen the cool retreat along the river as the difference between heaven and hell. Gulping fresh air surely rejuvenated the survivors as they staggered away into the night.

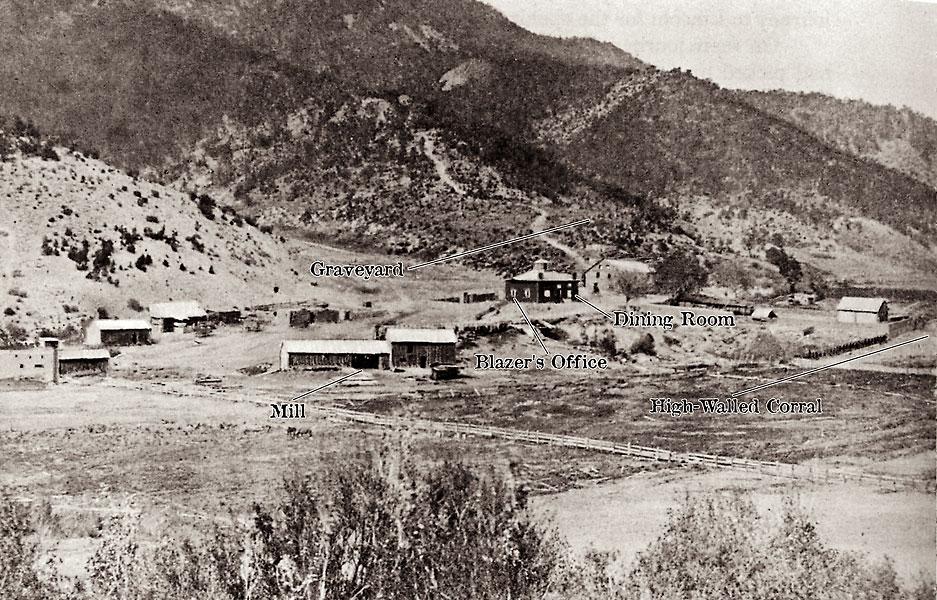

Salazar was one of the 14 Regulators who tried to escape the McSween home. Yet when he made his desperate break, he was shot in the back and shoulder. Knowing he had to be more clever than the enemy, the teenager lay still in a pool of his thickening blood, pretending to be dead. Time passed slowly. He continued his charade despite being kicked and abused. Eventually, in the dead of night, he crawled to his sister-in-law’s house, and she miraculously smuggled him to Dr. Dan Appel at Fort Stanton.

Being so badly wounded could have been what saved him in the long run. Salazar lay low, nursing his wounds. By the time Salazar recovered, the Kid was a hunted criminal. Salazar had more ventures into the outlaw world left for him, but the pull of family was beginning to leave its mark on the young man.

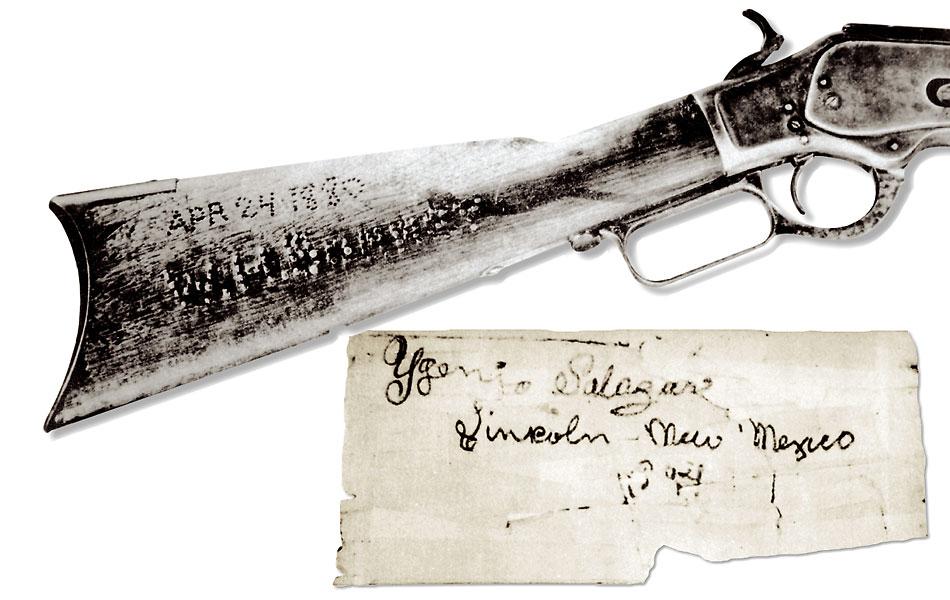

Almost three years later, after the Kid escaped from jail in Lincoln, legend has it that he rode out of town and fled to Salazar’s home, where his friend cut off the Kid’s shackles and fed him. That was probably the last contact the two had, although some claim that they saw each other afterwards at Fort Sumner.

The sheer brutality of the Lincoln County War continued in waves afterwards. Outlaws flooded the region from Arizona and Texas to enjoy the benefits of cattle rustling, bootlegging and counterfeiting. Even though Fort Stanton was established in 1855 to counter the violence of Apache raids, not even the military could have prevented the Lincoln County War. In fact, the fort’s coveted beef contracts may have been a cause of it. The fort had become the centerpiece for greed and political infighting that stretched as far north as Santa Fe. Conniving and chicanery were the

name of the game in gaining those military contracts.

The Kid and his gang of cattle rustlers, which included Salazar, ran rampant. Not until after Lew Wallace became governor did the violence lessen. After the tragedy of the five-day battle, the governor helped send Fort Stanton’s Col. Nathan Dudley, who had become a lightning rod because of his partisan ways, packing.

Peace eventually became the dominant force in the region, despite a few Apache raids here and there. The Fort Stanton cavalry forces transitioned out in 1896.

Perhaps fate, or despair at awakening to a new world without your comrades, caused Salazar to change his ways. Without loyalty to the Kid intervening, he found it easier to leave the outlaw trail. His life as a rancher and good citizen took precedence. He raised a talented family that enjoyed prosperity, even during the Great Depression. Several members of the family continue to reside in Lincoln County.

Everyday I pass by Salazar’s grave in the old Lincoln Cemetery. Everyday I am reminded that men like him, who may now be mere footnotes to history in comparison to men like Billy, were the true foundation for what was to come. Decades after the war, folks raised families, worked hard and achieved the American Dream. Salazar was among those men, but he started out his life as the “youngest outlaw.”

Photo Gallery

– Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell –

– Courtesy Kerr Family –

– True West Archives –

– Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell –

Yginio Salazar and Alexander McSween hide in the corner as Peppin’s men come in for the kill.

– Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell –

– Courtesy Frederick Nolan –