January 14, 1881

January 14, 1881

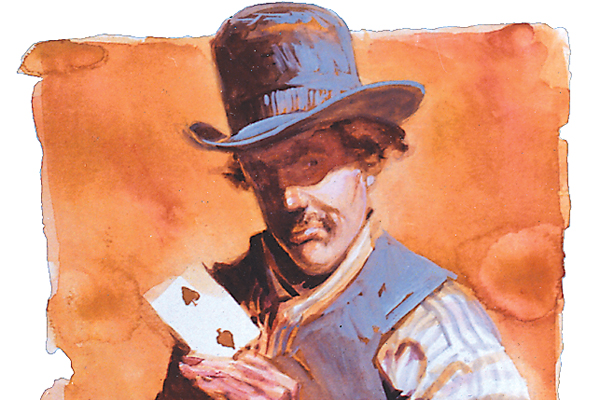

Siner and part-time gambler Mike O’Rourke, 18, and his roommate Robert Petty, 23, are eating in Smith’s rest-aurant in Charleston, Arizona.

It’s lunchtime, and Tombstone Mill & Mining Company’s chief engineer Phillip Schneider, 28, comes in and sits at the next table, joining A.E. Lindsey, a local telegraph operator.

Having finished his meal, O’Rourke gets up and walks over near the fireplace, sits on a stool and lights a cigar.

“You look cold Lindsey,” Schneider says to his tablemate. Lindsey admits he has “about half a chill.”

O’Rourke says, “Yes, it is cold.”

“I was not speaking to you,” Schneider replies. “I was talking to Lindsey.”

O’Rourke mutters, “Well, you’re a little too smart, anyhow.”

The mining engineer leaps to his feet and moves toward O’Rourke, waving his fist and saying, “That will do now, I don’t want any of that.” (O’Rourke later tells a reporter that Schneider called him a “d–d ——,” adding, “There were some ladies in the restaurant, and it made me awful mad to be called that.”)

Petty gets up and grabs Schneider by the collar, commanding him to “Take a seat.”

“You let go of me,” Schneider demands, but Petty holds him firmly until he complies.

O’Rourke heads for the door, yelling, “I will lick you when you come out.” Some two minutes later, O’Rourke returns and repeats his threat.

Petty gets up to leave, finally lighting a cigar that has been in his mouth since the altercation began. Outside, Petty finds O’Rourke and advises his roommate, “Let’s have no trouble.”

O’Rourke is armed with Petty’s pistol, which he has retrieved from their room. O’Rourke says he fears Schneider will “jump” him when he comes out.

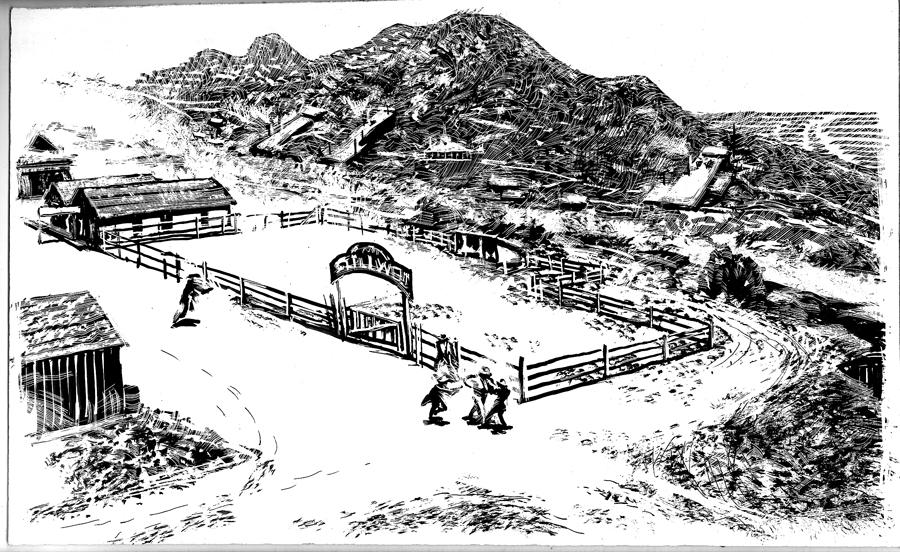

The two walk down near the corner of Frank Stilwell’s corral, where they again meet with the telegraph operator. “I think that old fellow is crazy,” says Lindsey, referring to Schneider.

All three decide to retire to a saloon for a drink, but as they turn to go up the street, they encounter Schneider, speedwalking toward them. He comes right up to O’Rourke and demands, “What the hell did you mean by talking to me in that way?”

Petty tries to intervene, but Schneider pushes him away, snarling at O’Rourke, “I see you have got a pistol but you need not think that I am afraid of it.”

O’Rourke holds out his left hand, warning Schneider to stay away from him, but Schneider keeps coming as he pulls out something from his coat.

Constable George McKelvey has been watching the encounter. When O’Rourke pulls the pistol, the lawman runs toward them, shouting, “Don’t you shoot!”

The pistol discharges, the bullet hitting Schneider above the upper lip on the left side of his nose, killing him instantly.

O’Rourke drops the weapon and starts running toward the San Pedro River.

Constable McKelvey races up, grabs O’Rourke’s pistol and demands that O’Rourke stop, but he keeps running. McKelvey’s weapon misfires, so he successfully fires O’Rourke’s pistol. Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce stops immed-iately and is arrested.

The fight is over.

The battle for a young gambler’s life has just begun.

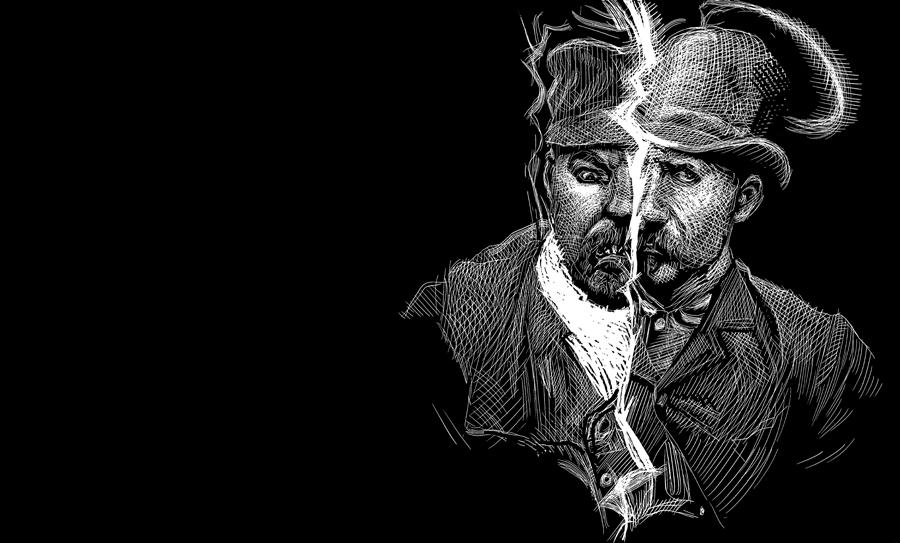

Phillip Schneider’s Dual Visage

Legend portrays the mining engineer as having a “herculean build, with a well-established reputation as a bully.”

But is this true?

Eyewitnesses to the fight testify that Schneider was “a muscular strong man, a little above the medium size.” O’Rourke’s portrayal of his adversary seems an exaggeration: “He had a knife in his hand. I was excited, of course, for the man was twice as big as I was.”

The Arizona Daily Citizen reports the day after the killing: “Mr. Schneider is a man respected by all” and “seems to have been universally liked.” His boss, Superintendent Richard Gird, describes Schneider as “a quiet, peaceable man.”

Would so many miners abandon their work to rally for vengeance, if Schneider was a known bully?

As for Schneider’s rudeness to O’Rourke, friends claim that his cabin had been burglarized and he suspected O’Rourke.

One witness does testify that Schneider threatened O’Rourke, saying, “I will cut you.” After the shooting, Schneider was found holding a three-inch long knife in his left hand, however, “the blade was closed.”

Also, keep in mind that all of Schneider’s alleged comments during the final confrontation are reported by O’Rourke, Petty and Lindsey. Hardly objective bystanders.

Was Schneider a big bully who deserved his death or a well-liked mining engineer who was murdered over a verbal slight?

Perhaps he was both: A hard- working mining man who took no guff and pushed a minor altercation to a tragic end.

A Wild Ride & Conflicting Motives

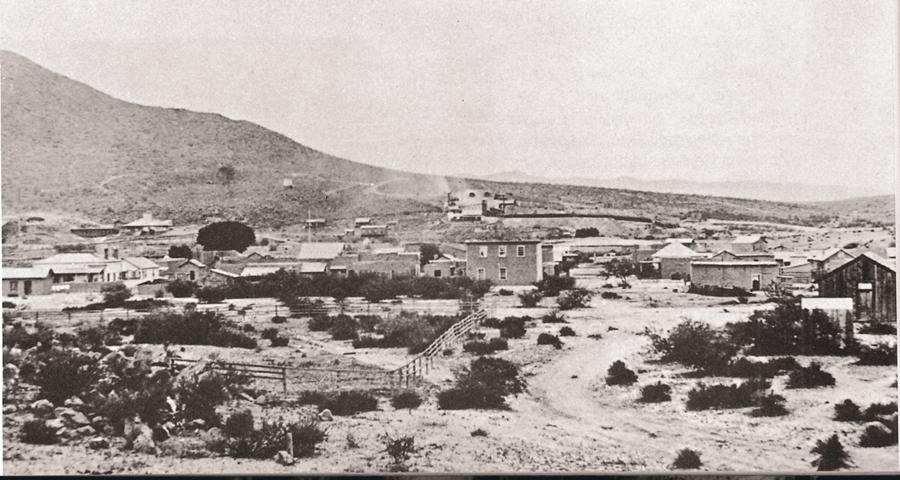

Word reached Charleston authorities that cow-boys were “preparing to take [O’Rourke] out of custody.” Fearing their prisoner will either be set free by the cow-boys or lynched by a growing number of angry miners, town officials put the prisoner in a wagon and Constable McKelvey slapped the reins for the 10-mile ride to Tombstone. Charleston authorities telegraphed Tombstone Marshal Ben Sippy, alerting him that the prisoner was on the way.

Soon after the 12:30 a.m. Schneider shooting, the following telegrams were sent from Charleston to Richard Gird in Tombstone (the mill was in Charleston; the mine, in Tombstone), warning of a possible rescue attempt.

Charleston, Jan. 14, 1:30 p.m.

To Richard Gird; Schneider has just been killed by a gambler; no provo-cation. Cow boys are preparing to take him out of custody. We need fifty well armed men.

Charleston, Jan. 14, 1:35 p.m.

To Richard Gird; Prisoner has just gone to Tombstone. Try and head him off and bring him back.

Charleston, Jan. 14, 1:50 p.m.

To Richard Gird; Burnett has telegraphed to the officers who have the murderer in charge to bring him back

to appear at inquest. See that he is brought back.

Gird was “in the mine” and didn’t read the telegrams for a good hour after the transmissions began, reported the January 17, 1881, Tombstone Epitaph. When he finally did, he ordered “a number of the miners” to “report to the officers, to resist any attempted rescue of the prisoner.”

The “murderer” reached “the corner of Fifth and Allen a few minutes after the dispatches had been read” (about 2:30 p.m.). He possibly was escorted by Virgil Earp, who had picked him up along the way, and taken to Vogan’s Saloon.

Also, the Epitaph reported that “the officers, fearing pursuit, sent the murderer, who was on horseback, on ahead … it is certain that he came in ahead, his horse reeking with sweat.” (This report supports Wyatt’s later claim that Virgil had picked up O’Rourke from the wagon and brought him to town on horseback.)

Gird’s miners descended on Allen Street to demand the prisoner be taken back to Charleston. Some in the crowd may have been worked up, but Gird’s intentions were honorable.

“Mr. Gird himself [maintains the miners] were ordered to report to the officers, in keeping with the tenor of the dispatches received by him, to sustain the law,” the Epitaph reported.

It’s also significant that the miners faced a contingent of lawmen who appeared to be gamblers (Wyatt Earp was a faro dealer at the Oriental Saloon) and had hid their prisoner in Vogan’s Saloon. It’s not hard to imagine that the miners felt they were getting the short end of the stick (Curly Bill Brocius had recently dodged justice and caused havoc in Charleston mere weeks before).

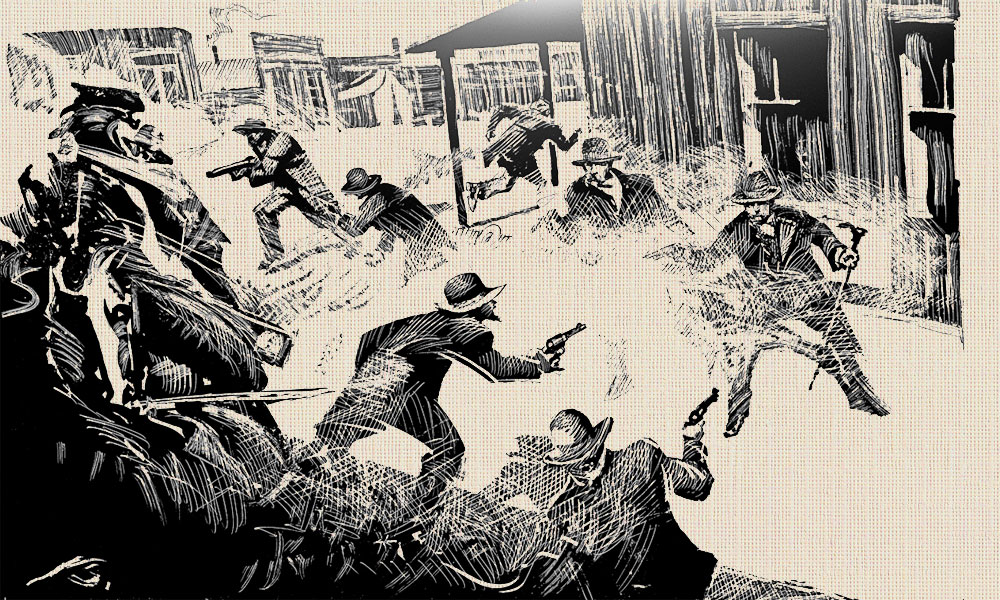

Tombstone Standoff

When Virgil Earp rode up with Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce and de-posited him at Vogan’s Saloon, an angry crowd soon formed. The following description was reported in the January 17, 1881, Epitaph.

“In a few minutes Allen street was jammed with an excited crowd, rapidly augmented by scores from all directions. By this time Marshal Sippy, realizing the situation at once, in the light of the repeated murders that have been committed and the ultimate liberty of the offenders [referring to Curly Bill Brocius’ recent release], had secured a well armed posse of over a score of men to prevent any attempt on the part of the crowd to lynch the prisoner; but feeling that no guard would be strong enough to resist a justly enraged public long, procured a light wagon in which the prisoner was placed, guarded by himself, Virgil Earp and Deputy Sheriff Behan, assisted by a strong posse well armed. Moving down the street, closely followed by the throng, a halt was made and rifles leveled on the advancing citizens, several of whom were armed with rifles and shotguns. At this juncture, a well known individual with more averdupois than brains, called to the officers to turn loose and fire in the crowd. But Marshal Sippy’s sound judgment prevented any such outbreak as would have been the certain result, and cool as an iceberg he held the crowd in check. No one who was a witness of yesterday’s proceedings can doubt that but for his presence, blood would have flown freely. The posse following would not have been considered; but, bowing to the majesty of the law, the crowd subsided and the wagon proceeded on its way to Benson with the prisoner, who by daylight this morning was lodged in the Tucson jail.”

Rushes Made, Rifles Leveled

Well, Mr. Stanley arrived by today’s stage … Mr. [Stanley] came by way of Santa Fe and had a rough time of it, narrowly escaping an over-hauling by road agents. Of course, a long talk was in order and Mr. S and I took the street for it and got into the midst of terrible excitement on the main street. A gambler called Johnny Behind the Deuce, his favorite way at faro, rode into town followed by mounted men who chased him from Charleston, he having shot and killed Schneider, engineer of T.M.&M. company. The officers sought to protect him and swore in deputies, themselves gambling men (the deputies that is) to help. Many of the miners armed themselves and tried to get at the murderer. Several times, yes a number of times, rushes were made and rifles leveled, causing Mr. Stanley and me to get behind the most available shelter. Terrible excitement, but the officers got through finally and out of town with their man bound for Tucson. This man should have been killed in his tracks. Too much of this kind of business is going on. I believe in killing such men as one would a wild animal. The law must be carried out by the citizens, or should be, when

it fails in its performance as it has lately done.

“Another buggy was procured and Sippy and Deputy Sheriff Behan got into it; with Rourke [sic] between them, and rode off accompanied by fifteen men well-armed with rifles, the latter accompanying them a distance of twelve miles.”

—January 15, 1881, Arizona Daily Citizen

Did Wyatt Earp Hold Off the Mob by Himself?

Starting with Stuart Lake and his book Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal (1931), Wyatt Earp is portrayed as single-handedly holding off the O’Rourke lynch mob. This is at odds with the newspaper accounts and Parsons’ diary, neither of which mention Wyatt’s name (the Tucson Citizen gives credit to “Deputy United States Marshal Virgil Earp and his companions”).

In the late 1920s, however, George Parsons wrote Lake, claiming Wyatt Earp had displayed considerable “nerve” during the incident. Parsons went on to write, “Wyatt, I could see him now as his team went down the street, he backed his horse down the street fronting the mob and lowered his rifle every now and then on them when a rush was attempted.” Parsons ends with “it was a very nervy proposition, particularly on the part of Wyatt.”

Even in this latter-day account, Parsons doesn’t claim that Wyatt acted solo. “His team” went down the street, and it was “a nervy proposition particularly on the part of Wyatt,” which presumes he was part of a larger posse.

In spite of the lack of evidence, it’s probably safe to say Wyatt helped his brother Virgil and Marshal Sippy hold back the mob. It would have been totally in his nature and makeup for Wyatt to step forward into the breach. But it’s also ludicrous to think that Wyatt did it all by himself.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

The 15-man posse rode with Deputy Sheriff John Behan, Constable George McKelvey and Marshal Ben Sippy for 12 miles. Although threats were made that the mob would intercept them at Pantano by taking a shortcut, no action materialized. The prisoner was delivered without incident to the Tucson jail.

On February 1, 1881, Justice Joseph Neugass ordered that Mike O’Rourke be held in the county jail, without bail, to await trial for his murder charge. Before the next Grand Jury convened, O’Rourke escaped on April 18, 1881, while he and other prisoners were in the jail yard prior to the evening lockdown. The Epitaph speculated that for about 20 seconds, the prisoners were out of the guards’ sight, and someone “threw him up so that he could grasp the top of the wall.” No easy task since the wall was a reported 16 feet high. (The Grand Jury officially indicted him on May 19.)

The last sighting of O’Rourke was reported in the Epitaph on May 13: “‘Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce’ was seen three days ago, we are informed, in the Dragoon Mountains. He was well mounted and equipped, and was on the eve of departure for Texas. The climate of Arizona, he said, did not agree with him.”

The miner’s fears came true: Mike O’Rourke had escaped justice.

Recommended: Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce by Steve Gatto, published by San Simon Publishing Company.

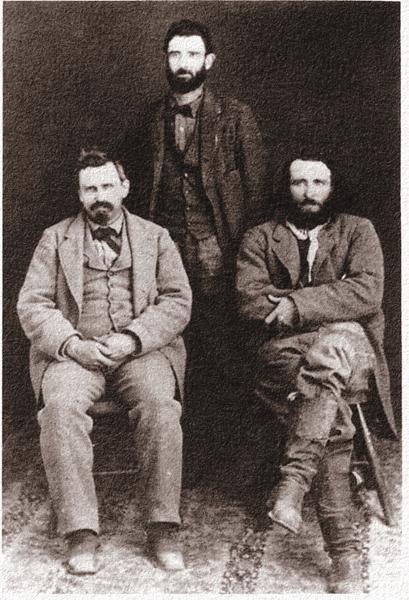

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

– True West Archives –