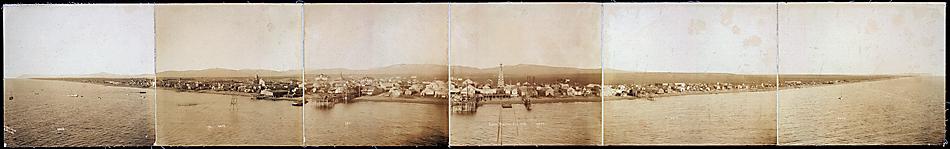

The stars fill the dark sky. The night is deadly cold in the winter of 1872. Near Cape Nome, Alaska, the dead are seen trying to return to this world.

The stars fill the dark sky. The night is deadly cold in the winter of 1872. Near Cape Nome, Alaska, the dead are seen trying to return to this world.

Arching over the barren landscape of the Inupiat village of Ayasayuk, high in the sky, are the intermittent appearances of the ancestors’ ghostly figures. In tumbling colors of purples, yellows, reds and green, like faces peering around giant curtains, the souls of the dead have come back to observe the living. Or so many here believed, when gazing upward at the Northern Lights, they could see the souls silently cascading down from a dark heaven.

That night a child is born, the third to father Anatwanuk and mother Anyayak. He is Angokwazhuk. But the newborn and family are living at the fragile edge of survival on a frozen frontier as far west as America stretches. Within a few years, the boy’s father and one sister are dead, and his mother has moved her remaining two children to the Diomede Islands between Russia and Alaska.

Her decision and the Artic changed her son’s life forever. Though still young, Angokwazhuk earned a reputation as a skilled hunter. But on one hunting expedition with a childhood friend, the two became trapped upon drifting ice and were unable to return to shore. The sea ice trapped them for a month during the darkness of winter. He survived. His friend died. Finally, he was able to reach a shoreline but unable to walk, he slowly dragged himself home. Both feet were frozen and were amputated at the ankles.

Angokwazhuk would never hunt again and learned to walk on two stumps. Economic survival shifted from hunting—to carving the remains of others’ hunts. He joined his Inupiat ancestors in their tradition stretching back 2,000 years of carving ivory as tools and artwork.

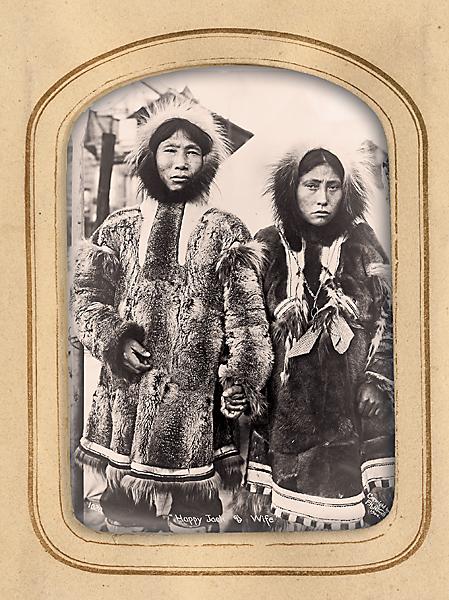

In 1892, a whaling ship captain hired the 19-year-old Eskimo to teach him the centuries-old art of scrimshaw. Angokwazhuk’s shipmates gave him the permanent moniker of “Happy Jack.” His time on the whaler introduced him to another culture and transformed him as an artist. He now carved Western objects for sale: cribbage boards, miniature whaling ships and engraved walrus tusks. He enhanced his careful-incisions with India ink, graphite and ashes, even startlingly, reproducing perfect imitations of newspaper photos in halftones with the use of a needle and ink.

Happy Jack supported his family with a substantial income, influencing numerous young Eskimos to become artists. Ironically, he became such a celebrity of his era, as an artist and as a popular personality, that many unknown carvings have been mistakenly credited to him. He could never read or write, and thus rarely signed many of his carvings, only copying his name when asked.

In 1918, the worldwide Spanish influenza pandemic traveled to the Alaskan frontier and Happy Jack, 46, became another, in the millions of deaths. Fortunately for us, his spirit and life live on through his timeless art—and courageous life story of survival and courage.

Tom Augherton is an Arizona-based freelance writer. Do you know about an unsung character of the Old West whose story we should share here? Send the details to editor@twmag.com, and be sure to include high-resolution historical photos.

Photo Gallery

– photos Courtesy Library of Congress –