November 6, 1908

November 6, 1908

Two Mules for Aramayo

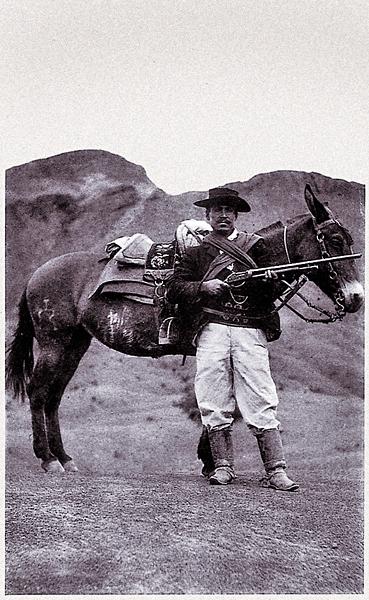

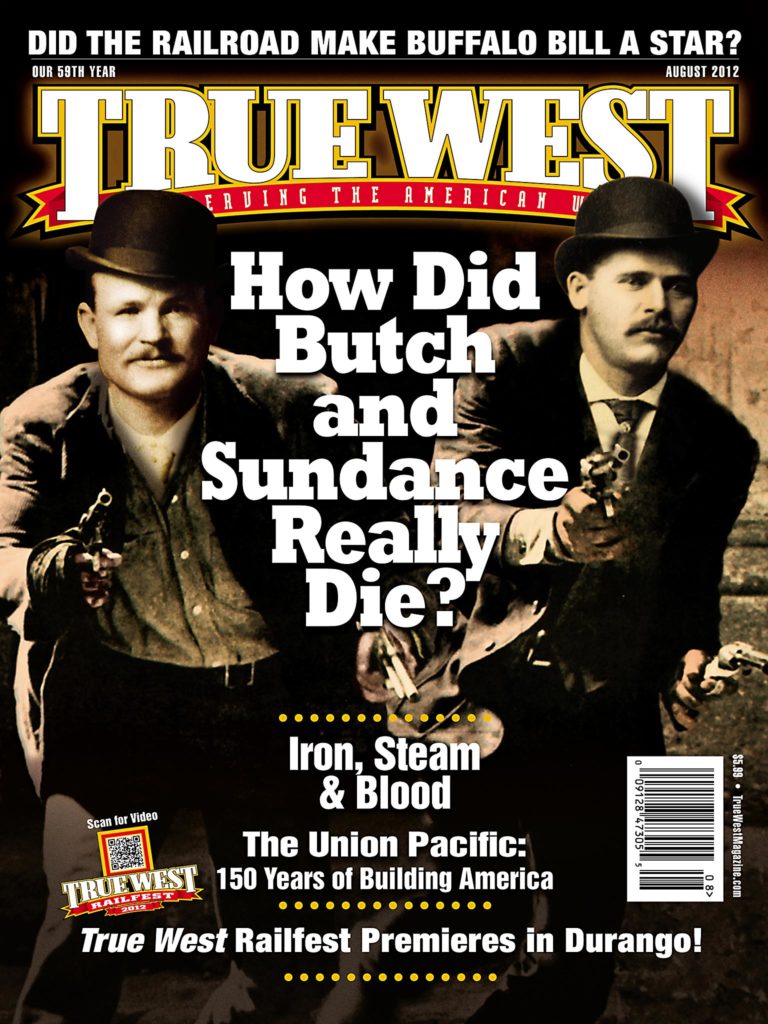

Two heavily armed “Americanos on jaded mules” ride into the high mountain village of San Vicente, Bolivia.

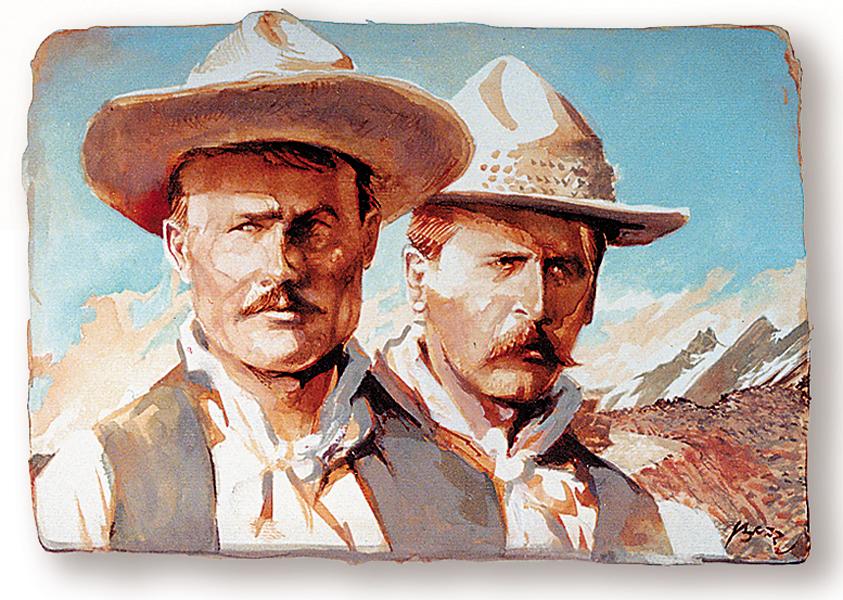

As the sun is setting, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid rein in at the home of Bonifacio Casasola. A village official, Cleto Bellot, approaches the strangers and asks what they want.

“An inn,” they tell him.

Bellot informs the strangers there are no inns in San Vicente, but that Casasola can put them up and sell them fodder for their mules.

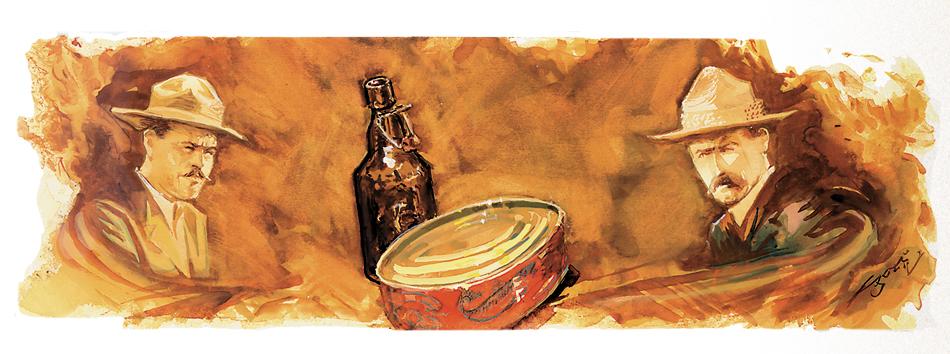

After tending to their animals and unloading their gear, Butch and Sundance join Bellot in their room, which opens onto Casasola’s walled patio. The Americans ask Bellot about the road to Santa Catalina, an Argentine town just south of the border (this was probably a ruse to throw off any pursuing posses) and the road to Uyuni (their real path), located about 75 miles north of San Vicente. They also ask where they can get sardines and beer; Bellot sends Casasola to buy some.

After more small talk, Bellot leaves and goes to the home of Manuel Barran, where a four-man posse from Uyuni is staying. The posse rode in that afternoon, warning Bellot and other locals to be on the lookout for two Yankees with a mule belonging to the Aramayo mining company, whose payroll was recently robbed.

The posse consists of Capt. Justo P. Concha, two soldiers from the Uyuni Garrison and Uyuni Police Inspector Timoteo Rios. Captain Concha is unavailable when Bellot arrives. After Bellot tells his news to Inspector Rios and the two soldiers, they immediately load their rifles.

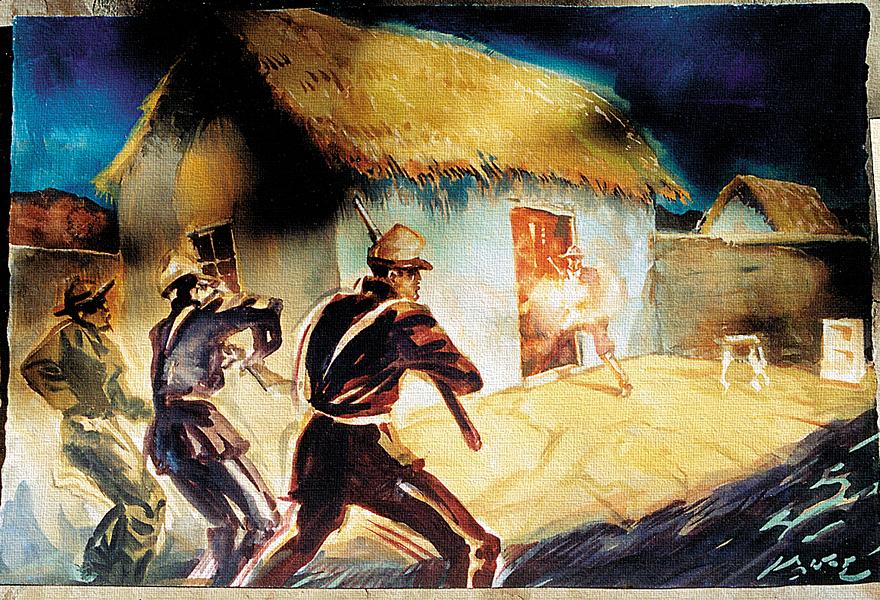

Accompanied by Bellot, the three posse members march to Casasola’s home and enter the patio. As the Bolivians approach the bandits’ room, Butch appears in the doorway, draws his Colt and fires, hitting lead soldier Victor Torres in the neck. Torres gets off a shot with his rifle, then runs out the patio door and collapses at a nearby house. He dies within minutes.

The other soldier and Inspector Rios also return fire, before they scurry out with Bellot. After retrieving more ammunition, the two return and fire into the house through the patio door.

By now, it’s dark. Captain Concha runs up and commands Bellot to find some locals who can watch the roof and the back of the adobe house so the bandits don’t punch a hole and escape. As Bellot rushes to comply, he hears “three screams of desperation” coming from the bandits’ room.

The San Vicenteños are finally at their posts, but the firing has ceased and all is quiet. Minutes turn into hours, with no response from the fugitives. The guards remain at their stations throughout the bitterly cold and windy night.

The next morning, Bellot and others enter the room and see Butch’s lifeless form stretched out on the floor, one bullet wound in the temple and another in the arm. Sundance’s corpse sits on a bench behind the door, hugging a large ceramic jar. He has been shot once in the forehead and several times in the arm. According to one report, the bullet removed from Sundance’s forehead came from Butch’s Colt.

From the positions of the bodies and the locations of the fatal wounds, the witnesses conclude that Butch put his partner out of his misery, then turned his gun on himself.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

The bodies of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were buried in the local cemetery that afternoon. The Aramayo payroll was found intact in their saddlebags. Captain Justo P. Concha absconded to Uyuni with the lot, leaving the Aramayo company to battle for months in court to recover its money and mule.

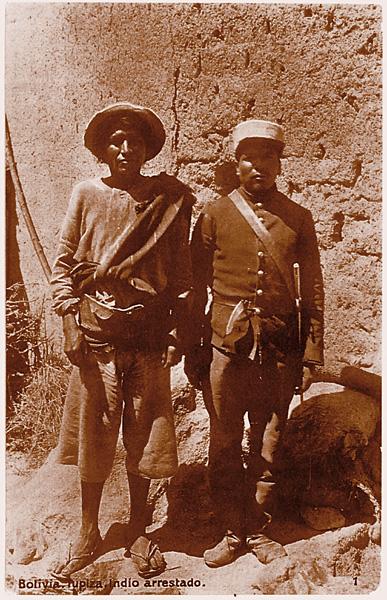

Two weeks after the shoot-out, the bandits’ bodies were disinterred, and Carlos Peró (the Aramayo manager) identified them as the same pair who had held him up. Tupiza officials conducted an inquest of the robbery and shoot-out, interviewing Peró, Bellot and several others, but were unable to ascertain the dead outlaws’ names.

In July 1909, Frank D. Aller, the American vice-consul in Chile who knew Sundance, wrote the American legation in La Paz, requesting the death certificates for Frank Boyd or H.A. Brown and Maxwell. Boyd had been Sundance’s alias in Chile; Brown and Maxwell were aliases that he and Butch had used in Northern Bolivia. The legation forwarded his request to Bolivia, stating that the Americans had “held up several of the Bolivian Railway Company’s pay trains, and also the stage coaches of several mines, and . . . were killed in a fight with soldiers that were detached to capture them as outlaws.”

Numerous stories circulated about Butch cheating death in Bolivia and returning to the States. The most persistent tale was put forth by Lula Parker Betenson, one of Butch’s sisters, who insisted Butch had visited the family in 1925. Others in the family disagree, saying that Butch never returned, but Lula still has her believers.

In 1937, an elderly Matt Warner, a former member of the Wild Bunch, scribbled a note to historian Charles Kelly: “Forget all the reports on Butch Cassidy, they are fake. There is no such man living as Butch Cassidy. His real name was Robert Parker, born and raised in Circle Valley, Utah and killed in South America, he and a man by the name of Longwow [sic] we[re] killed in a soldier post their [sic] in a gun fight. This is straight.”

Recommended: Digging Up Butch & Sundance by Anne Meadows, published by University of Nebraska Press; Sundance, My Uncle by Donna Ernst, published by The Early West.

Photo Gallery

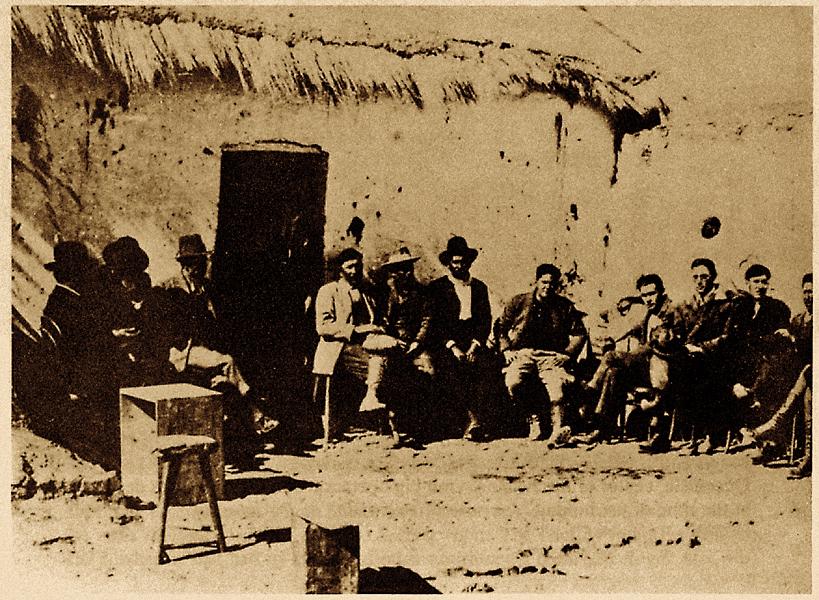

– Photo courtesy Daniel Buck and Anne Meadows –<br/

– Illustration by Bob Boz Bell –

– Illustration by Bob Boz Bell –

– Illustration by Bob Boz Bell –

– By Victor J. Hampton –

– Photo courtesy Daniel Buck and Anne Meadows –<br/