The most surprising thing about homosexuality in the Old West is not that it was rare in the rugged, macho world of the cowboy, but that it was so common and so not a big deal.

That’s a complete reversal of the popular notion that the West was populated by virile, heroic men who could live for months on the open range with little more than their rope, their horse and, of course, the ultimate phallic symbol, their gun.

Thinking of these symbols of manhood as uniting sexually with other men is like finding out one of the Marlboro men died of lung cancer—it’s a disconnect that many will find uncomfortable.

In fact, History professor Clifford P. Westermeier noted any examination of sexual activity by cowboys—homosexual or not—was such a cautious topic, his article in the 1975 Red River Valley Historical Review was titled “Cowboy Sexuality: A Historical No-No?”

“To tamper with the image of a folk hero, a historic formula, a legend, and most of all, that of the American cowboy heritage is probably more dangerous than the proverbial where ‘fools rush in,’” Westermeier writes. He notes the traditional cowboy had four failings: drinking, gambling, lechery and violence. “Of these … lechery is often alluded to but is the least detailed activity of his frenetic pleasures.”

While most would expect the cowboy’s lechery was pointed towards women, that wasn’t always true, but it also didn’t mean what it would mean today.

“It’s important to know the history of homosexuality,” notes History Department Chairman Peter Boag from the University of Colorado at Boulder. “Society didn’t really designate people as homosexual or heterosexual through most of the 19th century; it was not really until the 20th century that those identities crystallized.”

Boag, who wrote the 2003 book Same Sex Affairs, explained to True West: “In all-men societies, it was not unusual for same sex relationships, and it was just an acceptable thing to do. People engaged in same sex activities weren’t seen as homosexuals.”

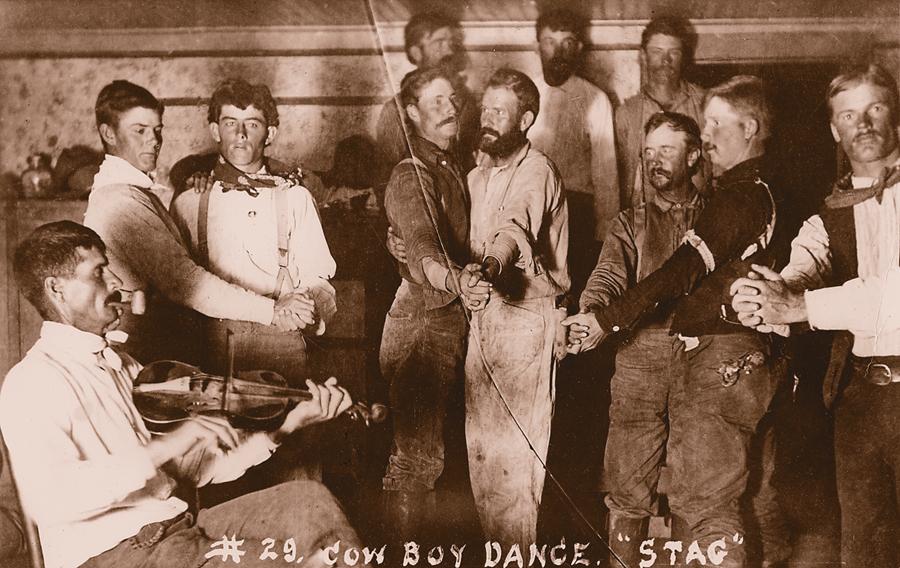

That point is strongly supported in the article, “Paradise of Bachelors: The Social World of Men in Nineteenth-Century America.” It notes: “Without the presence of women, the always unstable line dividing the homosocial from the homosexual—that is, dividing non-sexual male bonding activities from sexual contact between men—became even more blurred. As traditional notions of ‘normal’ gender roles were challenged and unsettled, men could display both subtly and openly the erotic connections they felt for other men. When the miners at Angel Camp in southern California held dances, half of the men danced the part of women, wearing patches over the crotches of their pants to signal their ‘feminine’ role.”

But nobody would have called them gay or even homosexual—a word that wasn’t even used until 1868. (Heterosexual is an even newer word, which first appeared in print in 1924.)

They may have been called punk, notes Patricia Nell Warren in a 1997 article in Quest magazine. “Punk—used today in men’s prisons to denote a young male sexual partner, was common in old-time ranch lingo because of sexual relationships among cowboys,” she writes. There was even a name for same-sex “marriages.” As “Paradise of Bachelors” notes: “Cowboys and miners settled into partnerships that other men recognized (and sometimes referred to) as ‘bachelor marriages.’”

American Indians, meanwhile, openly recognized and had a name for men and women of an “alternative gender”—those who preferred to dress and work as the opposite sex. Anthropologists now use the term berdache.

“Zunis believed that men skilled at women’s crafts (and women skilled in male activities) combined the two sexes,” writes Will Roscoe in The Zuni Man-Woman, published in 1991. “This made them extraordinary in every respect.” He found male and female berdaches documented in over 130 North American tribes, in every region of the continent. “In traditional native societies berdaches were not anomalous,” he notes. “They were integral, productive and valued members of their communities. But the European culture transplanted to America lacked any comparable roles, and the Europeans who saw berdaches were unable to describe them accurately or comprehend their place in Indian society.” His book focuses on “Zuni maiden” We’wha, whom he calls “perhaps the most famous berdache in American Indian history.”

None of this is news to those who have paid attention to such things. As early as 1948, Alfred C. Kinsey in Sexual Behavior in the Human Male shocked many when he found “the highest frequencies of the homosexual we have ever secured anywhere have been in particular rural communities in some of the remote sections of the country.”

He goes on to explain: “There is a fair amount of sexual contact among the older males in Western rural areas. It is a type of homosexuality which was probably among pioneers and outdoor men in general. Today it is found among ranchmen, cattle men, prospectors, lumbermen, and farming groups in general—among groups that are virile, physically active. These are men who have faced the rigors of nature in the wild. They live on realities and on a minimum of theory. Such a background breeds the attitude that sex is sex, irrespective of the nature of the partner with whom the relation is had. Sexual relations are had with women when they are available, or with other men when the outdoor routines bring men together in exclusively male groups.”

In a less scholarly approach, this old Western limerick makes the same point:

Young cowboys had a great fear

That old studs once filled with beer

Completely addle’

They’d throw on the saddle

And ride them on the rear.

Homosexuals themselves had “code words” to let each other know their preferences. If someone evoked anything associated with Walt Whitman—the name, image or writings of the famous American poet—it signaled they shared Whitman’s preference for men.

One of the most controversial aspects of this question is how the Mormon Church dealt with homosexuality in its early years. Historian D. Michael Quinn who exposed the history has been excommunicated. He found the same ideas within American religion as in cowboy bunkhouses: men and women were allowed to express intimacy in the 1800s, and this was not only accepted but encouraged.

Quinn quotes Mormon Founder Joseph Smith as writing that male friends “should lie down on the same bed at night locked in each other’s embrace talking of their love.” Smith said he did so himself.

Arguing that homosexual behavior was not considered as grave a sin as heterosexual adultery, Quinn claims Mormon leaders and judges “were more tolerant of homoerotic behavior than they were of every other non-marital sexual activity.”

All of this has been seen as so contrary to the Western myth that until now, even Hollywood has shied away. If you’re a student of Western movies, you probably can think of only one openly gay character in the thousands of movies over all these years—and that was a gay Indian character in Little Big Man. Some would suggest it was okay for Western fans to see a comical gay Indian on the screen, since Indians were often portrayed as the “enemy” anyway, while it would not be okay to portray a homosexual cowboy. (Of course, there was Joe Buck, who was a stud in both sexual persuasions in Midnight Cowboy, but most don’t consider that a Western movie.)

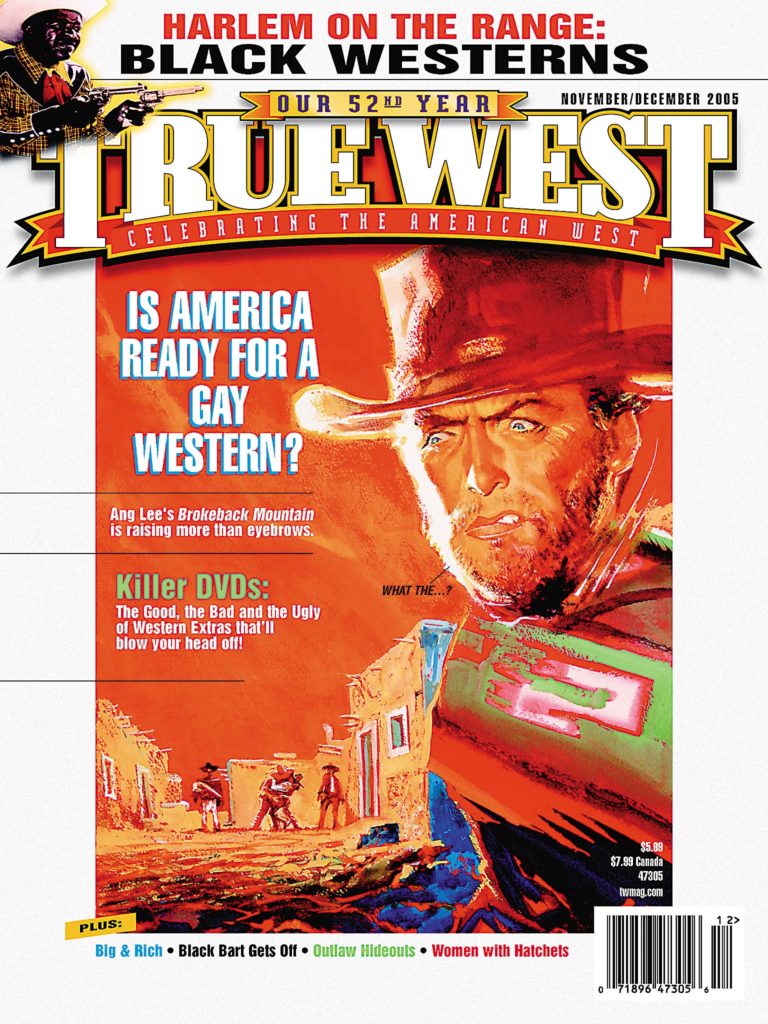

Coming to theaters soon, however, is a real Western that addresses the homosexual theme: Brokeback Mountain, starring Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal (see p. 72).

Based on a short story by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Annie Proulx, the movie is directed by Academy Award-winner Ang Lee. It’s called an “epic love story set against the sweeping vistas of Wyoming and Texas.”

Producer James Schamus has said it is “a very, very old-fashioned love story,” and explained, “Ang is fascinated with those moments in life where you’re touched by greatness and emotion but social rules and regulations keep you from following it.”

As Focus Features describes its own movie: “Brokeback Mountain tells the story of two young men—a ranch hand and a rodeo cowboy—who meet in the summer of 1963, and unexpectedly forge a lifelong connection, one whose complications, joys and tragedies provide a testament to the endurance and power of love.”

Was Abe Lincoln gay?

It isn’t clear if Western buffs are more homophobic than the general population, but it is true that if you want to rankle, just suggest a Western icon was a “homo.”

Take Wild Bill Hickok, who was described by one writer as having “feminine looks and bearing.” Someone else pointed out that he wore his hair long, apparently unaware that many Western men wore their hair long.

When Hickok was declared a “fag,” Hickok expert Joseph Rosa considered the suggestion absurd. “I am amazed that anyone should think of Hickok as gay,” he says. “I have never found any suggestion of it in any contemporary reference to him and in discussions with historians over the years have found that none of them even considered it.”

One writer has suggested that Doc Holliday may have enjoyed Big Nose Kate because she was so ugly she looked like a man.

And there’s the story of the “wife” of one of Custer’s aides, who wasn’t discovered to be a man until he was being prepared for burial (see p. 118).

But if any of the big names in Western lore were gay, it remains a secret.

The most “famous” person in Western history to be “outed” is Abraham Lincoln—the man who freed slaves and founded the modern Republican Party.

This past May, a gay advocacy group held a national celebration at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall to mark the 40th anniversary of the gay civil rights movement. Among the events was a discussion of “closeted public leaders.” Most prominent among them was Honest Abe.

In the book, The Intimate Life of Abraham Lincoln, the late writer C.A. Tripp—a homosexual and psychologist who was a researcher for Kinsey—makes a strong argument that the 16th president of the United States was a bisexual man. (After all, Lincoln did have four children.)

“Anyone not blinded by homophobia will recognize that the president who preserved our republic was gay,” declares Malcolm Lazin, executive director of Equality Forum, which organized the May celebration.

Tripp wrote that Lincoln had a love affair with a handsome youth and store owner, Joshua Speed, when both were young men in Springfield, Illinois. They shared a bed for four years. But that wasn’t necessarily telling, since sharing a bed wasn’t uncommon in those days. What most see as compelling are the letters the men exchanged while both were preparing to marry. The letters literally gush—some dismiss this idea, too, saying gushing letters were the norm then.

Author Gore Vidal, himself a homosexual who knew Tripp, thinks the proof is clear. “All evidence suggests that Lincoln’s stepmother got it right when after Lincoln’s death she said, ‘He was not very fond of girls,’” Vidal wrote for Vanity Fair’s website.

Much of the hubbub about this, of course, is that it was the Republican Party that Lincoln founded—the party now leading the vanguard against same-sex marriages and any other rights for homosexuals. If Lincoln had founded the Democratic Party, which is far friendlier to the civil rights aspect of homosexuality, there would be little gnashing of teeth.

What about the gals?

All historians writing about this subject bemoan the lack of information on lesbians in the Old West. Part of that is due to the age-old problem that history has often ignored the women in order to concentrate on every nuance of the men. But part is also that lesbian women were hard to identify. Women have forever had close female friendships, and those that were sexual could easily be disguised. In addition, men have never reacted as negatively to female same-sex activities as they have to men’s.

But none of that applies to George Parsons, whose journal in 1880 from Tombstone is absolutely aghast at the lesbian activity he witnessed at the local saloon: “This place holds some of the most depraved—entirely and totally so—that were ever known,” he wrote. “It would be impossible to speak here of some or one form of depravity I am sorry to know of—for bad as one can be and low as woman can fall.”

Western author Willa Cather is perhaps the most famous lesbian of the Old West era, at least, according to a 1988 book Gay Men & Women who Enriched the World by Thomas Cowan.

And yet again, American Indian cultures had far less problem with this subject than their Anglo neighbors. What today would be called a dyke was in Lakota society called a koskalaka, which translates as “woman who doesn’t want to marry,” writes Paula Gunn Allen in her essay “Beloved Women:?Lesbians in American Indian Cultures.”

“These women … do a dance in which a rope is twined between them and coiled to form a ‘rope baby.’ The exact purpose or result of this dance is not mentioned, but its significance is clear. In a culture that values children and women because they bear them, two women who don’t want to marry [a man] become united by the power of the Deity and their union is validated by the creation of a rope baby. It is clear that the koskalaka are perceived as powerful.”

Allen notes the Lakota also had a name for a “half-man and half-woman” who dressed and lived as women—winkte.

Attitude shifts

It wasn’t just the calendar that changed as the 19th century gave way to the 20th, but so did public attitudes about homosexuality.

While the 1800s were known to be “lax,” the new century saw an outwardly hostile and punitive approach to gays.

Some say the sensational Oscar Wilde trials in England at the turn of the 20th century helped push society over the edge; others say that the emergence of gays from the “closet” led to a growing fear.

Whatever the motivations, one reaction was the Eugenics movement of forced sterilizations that saw wide acceptance. Between 1900-80, some 60,000 Americans in 33 states were forcibly sterilized to stop them from having children and passing on their “bad genes.” (In one of the most humiliating legacies of this pseudo-scientific movement, the Nazis used the U.S. eugenics laws during WWII to justify their sterilization and mass murder programs.)

Several states included homosexuals in their list of “bad genes,” along with the feeble-minded, insane and the unwed mothers. Oregon, in particular, aggressively sterilized gay men and women. The state has since apologized for the “great wrong done.” (Several other states also have issued apologies, including Virginia, where many of the sterilized were blacks.)

And the Mormon Church, which once had been open to same-sex intimacy, helped lead the way in the 1950s for electro-shock therapy to “cure” homosexuals.

In the end, it’s clear that homosexual behavior wasn’t uncommon in the Old West, but it also wasn’t something you spoke about in polite society. Then again, neither was heterosexual behavior. There was nowhere near the openness about sex that there is today. In those clearer, calmer days, cowboys and townsfolk alike were far more comfortable with the attitude: “Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –