When you think of the savagery of the Old West, Minnesota doesn’t leap to mind. Montana, yes; South Dakota, yes; Arizona, yes, but not a Midwestern state that sits on the eastern edge of the West.

When you think of the savagery of the Old West, Minnesota doesn’t leap to mind. Montana, yes; South Dakota, yes; Arizona, yes, but not a Midwestern state that sits on the eastern edge of the West.

Yet, Minnesota played a pivotal role in the bloody conflict between whites and Indians that spanned nearly three decades: it was here that the first great Plains Indian war began; that one of the most notorious Indian uprisings took hundreds of lives, and where America saw its “greatest mass execution.”

The state was only four years old—most of its young men were off fighting the Civil War—when it was thrust into a second “war within a war in its own backyard,” one that catapulted Minnesota into what became known as the “Great Sioux Uprising of 1862.”

This event launched a series of Indian wars on the Northern Plains that didn’t end until the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890. But Minnesota is where it started.

And hunger began it.

Near Starvation

The crops had failed in 1861 and that winter had been one of near starvation for the Sioux who had sold 24 million acres of rich agricultural land and now lived on reservations, existing on the annuity payments for their property, which totaled some $3 million. But the 1862 payments that normally came in late June and early July didn’t arrive. By mid-August, Indians began showing up at agency headquarters, demanding food from the warehouses, which they would pay for once their checks came.

Some agency officials gave them food; others were stingy. Storekeeper Andrew J. Myrick callously remarked, “If they’re hungry, let them eat grass.” He would die for those words.

But it was a trivial egg-stealing incident that mushroomed into war: six weeks of bloody, brutal fighting that took the lives of at least 450 white settlers and soldiers—and maybe as many as 800—and a couple of dozen Indian warriors.

Chicken Eggs

As Chief Big Eagle told it, hunting had been unproductive for four weary and hungry Sioux warriors one hot August morning when they chanced upon a nest of chicken eggs near a farmhouse. One warrior took the eggs despite his companions’ warning that stealing from the whites would cause trouble. Dashing the eggs to the ground in anger, he shouted, “You are afraid of the white man, you are afraid to take eggs from him even though you are starving.”

According to Big Eagle, a companion angrily replied, “I am not afraid of the white man and to show I am not, I will go to his house and shoot him. Are you brave enough to go with me?” The others agreed to accompany him to the nearby homestead of Robinson Jones in Acton Township. Cunningly, they challenged Jones and his neighbors, Howard Baker and Veronius Webster, to test their marksmanship. A target was placed on a tree and the Indians and whites emptied their rifles at the mark. The Indians immediately reloaded, but the white men neglected to take that precaution. Suddenly, the Sioux turned on the settlers and brutally shot down Webster, Baker, Jones and his wife and Clara Wilson, their adopted daughter.

The four culprits, later identified by Big Eagle as Brown Wing, Killing Ghost, Breaking Up and Runs Against Something While Crawling, stole several horses and fled to their Rice Creek village on the Minnesota River. It was obvious to everyone that this was a bad situation—white women had been killed, which surely meant retaliation and possibly no more annuity checks.

The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862

Some chiefs immediately wanted to go to war; others urged caution, but all agreed only Little Crow had the ability and prestige to lead a successful attack.

Riders summoned Chiefs Mankato, Wabasha, Traveling Hail and Big Eagle to the home of Little Crow. As related by Big Eagle, Little Crow told the council, “Braves, you are like little children: you know not what you do. You are full of the white man’s devil water, you are like dogs in the hot moon that snap at their own shadows. We are like little herds of buffalo; the great herds are no more. The whites are as many as the locusts. Kill one or ten whites and ten times ten will come to kill you. Count your fingers all day long and the whites with guns will come faster than you can count.” Little Crow’s admonitions—which history would prove to be prophetic—went unheeded so he reluctantly agreed to lead the uprising.

The carnage began immediately. Small bands of Indians swooped down on unsuspecting homesteaders. The men were quickly gunned down and axed by the warriors while the women and children were assaulted and either killed or taken captive. After plundering the homes and barns, the Indians burned the farms and fields.

Encouraged by their early successes and the whites’ feeble response, the Indians turned their attentions to the settlements. Anticipating an easy victory, several hundred armed and painted Indians surrounded Lower Agency. The unarmed whites were quickly overwhelmed.

Andrew Myrick was among the first to die. He was found near his home, his mouth stuffed with grass.

The Sioux swept through the Minnesota Valley in an orgy of killing, raping, looting and burning. The whites who survived told of the bone-chilling war hoops that accompanied unmerciful attacks on loved ones. Panicked homesteaders fled to the larger settlements for safety, often relying on the walls of brick buildings to survive. One hotel, the two-story Dacotah House “was so crowded, the women had to remove their hoop skirts.”

One hero, a Christian Indian named John Other Day, led 62 whites across the river to safety. In retaliation, the Indians burned his farm and destroyed his crops. After the uprising, a grateful government awarded him $2,500 for his bravery.

The last significant battle occurred on September 23 when Col. Henry Sibley, who commanded a force of 1,619 men, faced off against 1,000 Indians. Sibley’s command camped at Battle Lake near present-day Echo. That night, the Sioux stealthily approached. At dawn, the raiders attacked in a fan-shaped formation, yet Capt. Mark Hendrick’s howitzers “mowed down the Indians like grass.”

It was a decisive victory for Col. Sibley. In a letter to his wife, he stated the Indians “received a severe blow and will not be able to make another stand.” His assumption was correct. There would be no more organized warfare by the Sioux in Minnesota. Now, the troops could concentrate on release of the captives and capture of the troublemakers.

Sibley was concerned Little Crow would kill all the hostages and indeed, the Sioux chief wanted to do just that. Fortunately, by this time, Little Crow’s influence had waned and the Indians refused to carry out his wishes. Chiefs Wabasha and Taopi were desperately trying to end the hostilities and Little Paul, a highly respected Sioux orator, spoke strongly in favor of ending the warfare and releasing the prisoners. As a result, Wabasha sent Joseph Campbell, a mixed-blood (people of mixed Indian and white ancestry), to let Sibley know the captives were safe and the soldiers could come for them.

Military Trial—“A Travesty of Justice”

The captives were held at a camp near the mouth of the Chippewa River near Montevideo. It quickly became known as Camp Release. Sibley, with an escort of troops, entered the Indian Camp, “with drums beating and colors flying.” An eyewitness wrote, “The poor creatures, half starved and nearly naked, wept with joy at their release.” The rescued numbered 269—mostly women and children—the men having been killed.

Sibley sent most of the rescued to Fort Ridgely; orphaned children were sent to settlements near their homes and most were adopted by relatives. Some women remained at Camp Release to testify at the trials of the Indians.

Nearly 2,000 Sioux were taken into custody and trials began almost immediately. A five-man military commission, headed by Col. William Crooks, prepared to try the accused.

Joseph Godfrey, a mixed-blood, greatly aided the prosecution. Godfrey was the first person tried and sentenced to hang, but his sentence was reduced to 10 years imprisonment when he agreed to testify. Intelligent and articulate, he helped convict many Indians. (Godfrey was released after three years and farmed peacefully near Niobrara, Nebraska, until his death in 1909.)

Urged to hurry, the commission settled as many as 40 cases each day, some lasting just five minutes. “Reading the records today buttresses the impression that the trials were a travesty of justice,” writes Kenneth Carley in his 1976 account of the uprising for the Minnesota Historical Society. “It is true that those in charge had to resist public pressure to do away with all the Indians, guilty and innocent alike, and it must also be pointed out that the trials were conducted by a military commission and not by a court of law. Nevertheless, many of the proceedings were too hasty and quite a number of prisoners were condemned on flimsy evidence.”

On November 5, the commission finished its work. Of 392 Indians tried, 307 were sentenced to hang and 16 were given prison terms. Col. Sibley approved all but one death sentence—the exception being the brother of John Other Day.

Most of the Indians were naive and couldn’t understand why they were being punished for honorable warfare. Many offered ridiculous extenuating circumstances. Some admitted firing only one or two shots, but argued they never hit anyone because they were such poor shots and their guns were inaccurate. Others claimed to be eating corn during the battles, while some had bellyaches and weren’t able to join the fighting. One admitted stealing a horse, “but it was a very small one.”

President Lincoln Names the Condemned

Sibley wanted to execute the condemned at once but was unsure of his authority. Therefore, on November 7, he forwarded a list of the condemned and complete records of their convictions to President Lincoln. The president received many appeals from the press, Minnesota Governor Ramsey and others urging immediate execution. Episcopalian Bishop Henry Whipple was one of the few who urged clemency: “This affair must not be settled with passion, but by calm thought.”

Lincoln heeded the advice of those seeking mercy and on December 6, 1862, commuted the death sentences of all but 39 warriors who had been convicted of wanton murder and rape. The president’s decision—he hand-wrote every name on Executive Mansion stationery—was unpopular with most Minnesotans. (One man on the list would later get a reprieve, leaving 38 to die.)

The condemned were held at Camp Lincoln but when enraged citizens threatened “frontier justice,” the Indians were moved to a more secure jail in Mankato to await execution on December 26.

On Christmas Day, families of the 38 were allowed a last visit. Most of the Indians were resigned to their fate. Rdainyanka, son-in-law of Chief Wabasha and a leader in the uprising, eloquently wrote his father-in-law, “I am set apart for execution and will die in a few days. My wife and children are dear to me. Let them not grieve for me. Let them remember that the brave should be prepared to meet death and I will do as becomes a Dakota.”

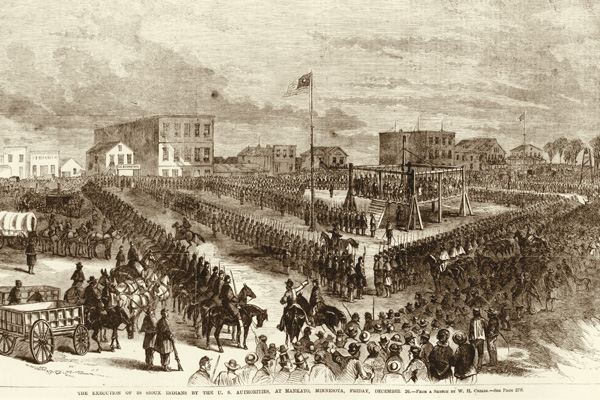

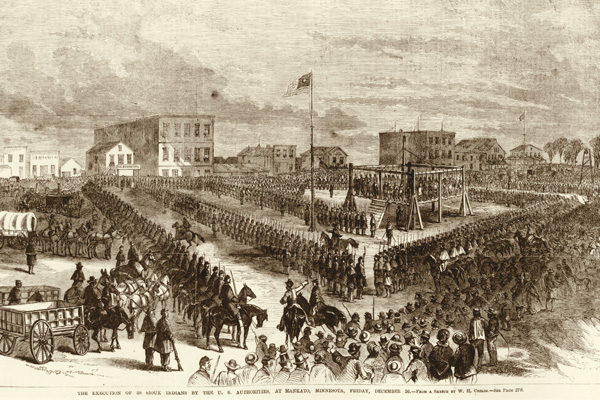

At dawn on December 26, the 38 began chanting their death songs. Their chains were removed and their arms were bound with ropes. At 10 a.m., they were taken from the prison to the huge wooden scaffold. Martial law had been declared and 1,400 soldiers surrounded the condemned. Thousands of civilians thronged the area to watch the proceedings. To a slow, measured drumbeat, the Sioux climbed the stairs of the scaffold. At the end of the third drum roll, William Duley, an uprising survivor, stepped forward and cut the rope to release the traps. As the 38 dropped to their deaths, there was a prolonged cheer from the soldiers and citizens. This would become known as “America’s greatest mass execution.”

Sioux War Aftermath

Little Crow, leader of the uprising, was conspicuously absent from the trials and punishment. When the fighting ended, he had fled to Canada. In June 1863, accompanied by 16 warriors, Little Crow returned to Minnesota to steal horses. It would be his last foray. Several whites were killed at this time and Little Crow’s band was assumed responsible. On July 3, the chief and his son Wowinapa were ambushed near Hutchinson by Nathan and Chauncey Lamson. Little Crow was killed and taken to Hutchinson where he was scalped, mutilated and buried in a pile of offal. In 1971, he received a more dignified burial when his remains were interred at Flandrau in a quiet ceremony. Little Crow’s grandson, 88-year-old Jesse Wakeman, said, “We decided Ta-O-Ya-Te-Dutah [Little Crow] should be buried among his own with only his own on hand.”

The executions weren’t the end of the Sioux Wars. Minnesotans retaliated against all Indians, whether they’d been involved in the uprising or not. “The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state,” Governor Ramsey declared. He demanded, and Congress agreed, that the Indians’ annuity money should be spent to compensate white victims of the uprising (even though some of the claims were so extravagant, they were outrageous).

The Minnesota government even persecuted a peaceful Winnebago tribe that had taken no part in the Sioux War. That the Winnebagos “lived on choice farm lands coveted by the whites raises a presumption that the settlers may well have been prompted by economic motives, coupled with fear and prejudice in wanting to get rid of the unfortunate Winnebago,” Carley writes.

And of course, this was just the beginning of blood that would flow for decades.

As Carley reports, “The Minnesota Uprising of 1862 was still fresh in the nation’s memory when it became aware of such Indian leaders as Red Cloud, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Bloody battles at Fort Phil Kearny, the Little Bighorn, and, in 1890, Wounded Knee, brought to an end at last the generation of Indian warfare that had begun at Acton in August, 1862.”

Larry H. Johns is a freelance writer who lives most of the year in Bloomington, Minnesota, but spends his winters in Arizona. He often writes about sports and logging and became fascinated by the 1862 uprising when he moved to Minnesota in 1965.