When we see an Old West photograph in a book or magazine, can we believe the subject is who or what it is said to be?

When we see an Old West photograph in a book or magazine, can we believe the subject is who or what it is said to be?

At one time, I believed everything I read or saw in a book. But then I learned that not everything in books is true.

Realizing this, I set two goals when I began collecting original photographs of the Old West: collect only photos that I think are authentic, and do what I can to improve the accuracy and quality of published photos in my collecting field. Both have been a challenge.

Too few photographs

Many of the Old West characters we “love”—Jesse James, Billy the Kid—were outlaws whose survival depended on being obscure. Accordingly, they rarely frequented photographers’ studios. Others who are well known today—Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson—were not famous enough in the 1880s for their photos to have been reproduced in large quantities for sale to the public. Most of their photos were originally owned by family or friends, and because they lived on the frontier, those photographs were few.

A number of books on the Old West contain bad or misidentified photos. Some writers spend years researching, wanting to find and verify every available fact. Then, at the last minute, they scramble to locate photos, often accepting poor quality images that have been used repeatedly. In addition, many have been poorly retouched, distorting the original image. Worse, there are a few individuals who have regularly provided writers with erroneously identified photos that then appeared in otherwise excellent books.

A million to one

The chance of finding an authentic photo of famous Old West characters in a flea market or antique mall is a million to one. Photos coming from present-day descendants are also often incorrect, especially when the photos don’t have an early identification or the subjects aren’t easily recog-nizable. Families want to own photos of famous people. An acquaintance once told me his family owned a photo of Pat Garrett. Through the years, the family had passed down the photo to succeeding generations, eventually misidentifying the man as Garrett instead of Wayne Brazil, the man who killed him.

Misidentified photos frequently find their way into libraries and museums where the personnel may not be qualified to screen out those that are incorrectly identified. Then, just by being there, the photos are considered authentic and are used in publications, further “authenticating” them.

Misidentification is often an honest mistake or wishful thinking. There is a great deal of the latter because of the high values attached to photos of famous Western characters. Although old photos are antiques, not all old-looking photos are antiques. Fakes do exist. For a photo to be fully accepted, it must meet certain standards.

Altering photos

The late Noah H. Rose collected photos during the 1930s-40s and provided them, at a price, to authors and publishers. Most of the photos were copy prints. Because many of Rose’s images were unclear, he often touched them up. In my opinion, Rose provided a service by preserving many authentic photos, but he did a disservice by his alterations.

Many of Rose’s retouched photos appear in The Album of Gunfighters, which Rose co-authored with J. Marvin Hunter in 1951. Most of the identifications in the book are accurate, however, I think the photos are of poor quality. Two erroneous photos of Sam Bass are “exposed” in the book, although they continue to be used to this day, and the only photo which I believe to be Bass is also included.

Judging Authenticity

A photo’s authenticity is best determined by:

1) Contemporary identification on the original photo.

2) Identification by someone who knew the individual.

3) Comparison with a known authentic photo.

Number 3 is unreliable if the comparison is not obvious. People see pictures differently, and some see similarities that aren’t there because they want the picture to be of someone it isn’t. A good rule is to never purchase an antique photo without examining it first.

Photo Gallery

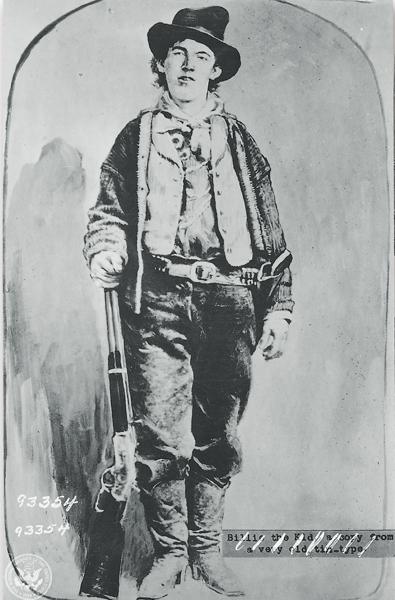

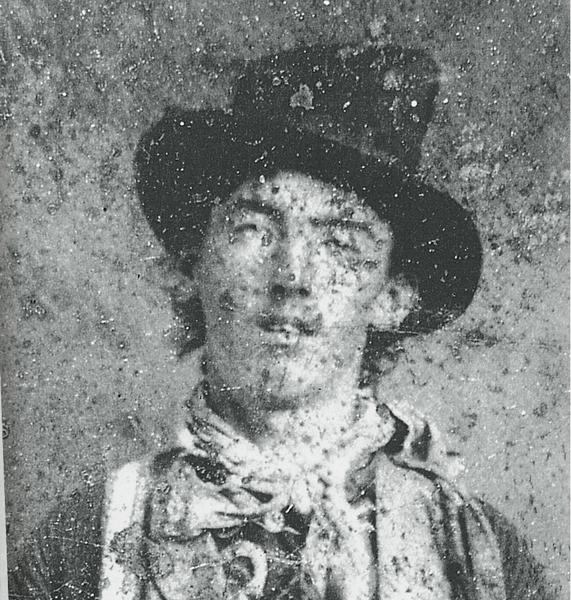

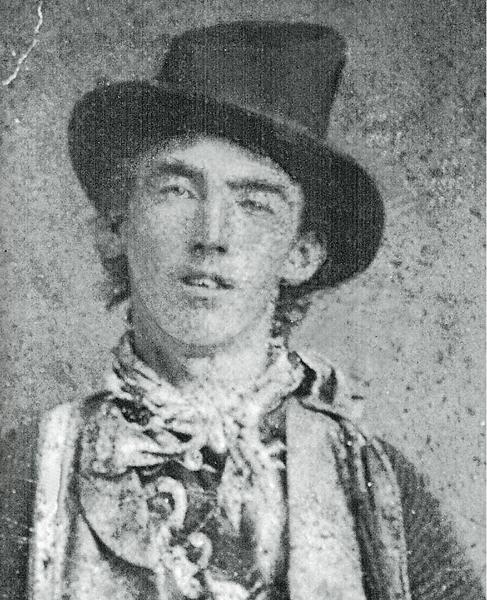

The greatest disservice the photo “menders” did to a Western figure was the restoration of Billy the Kid’s photograph. Rose’s retouching (above) turned a rather nice looking boy into an “adenoidal moron,” as some authors describe the modified photo of the Kid. Although better copies of the Kid’s tintype exist, writers continue using this terrible image.

The original tintype reveals a more pleasant looking young man.

When the tintype’s surface blemishes are removed and the “washed out” chin line is reestablished, we see how Billy probably looked. Nearly everyone who knew him said he was a decent looking guy who was popular with the girls. An orthodontist could have helped, but the Kid had other things on his mind.

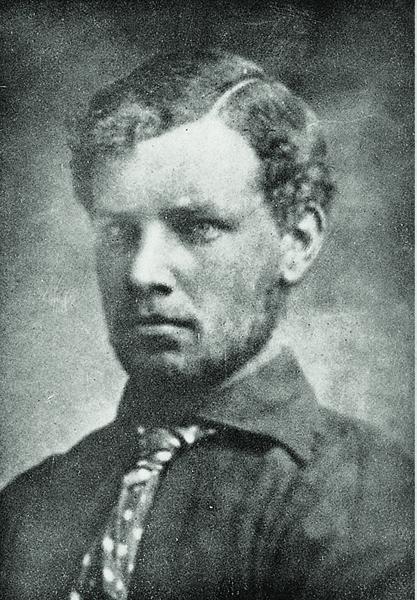

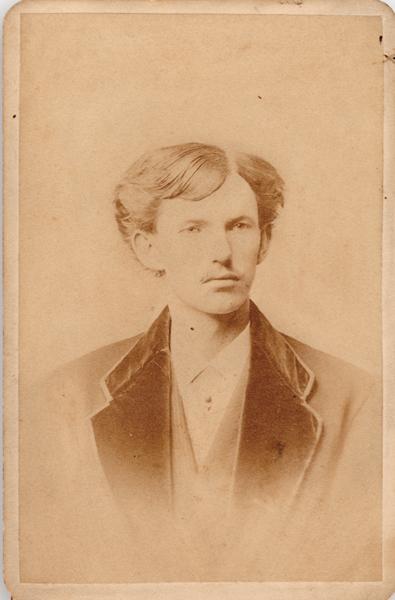

In 1949, a photograph of a handsome, blue-eyed, young man with curly blond hair was published as being Clay Allison. The photo has no clear justification for being so identified, but it is accepted by many.

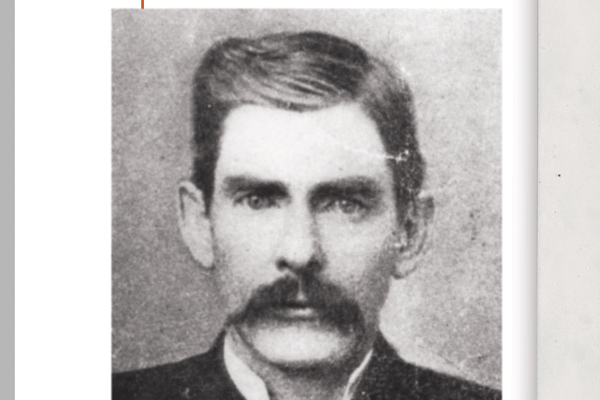

Later, several photos of a dark-haired Allison came to light. (One example is shown here.) Is the first one really him? I don’t know.

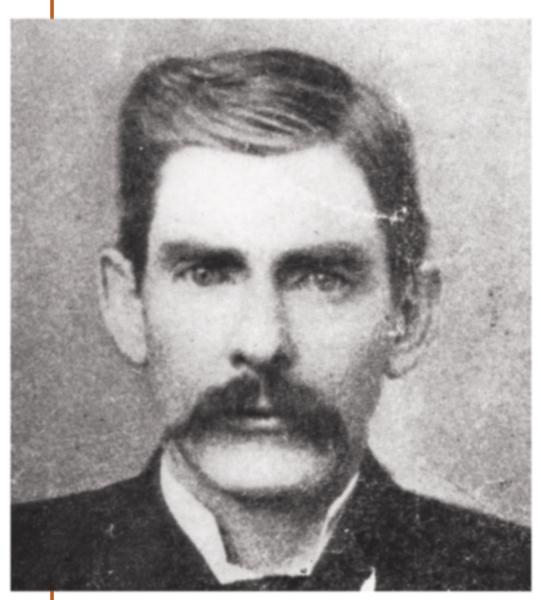

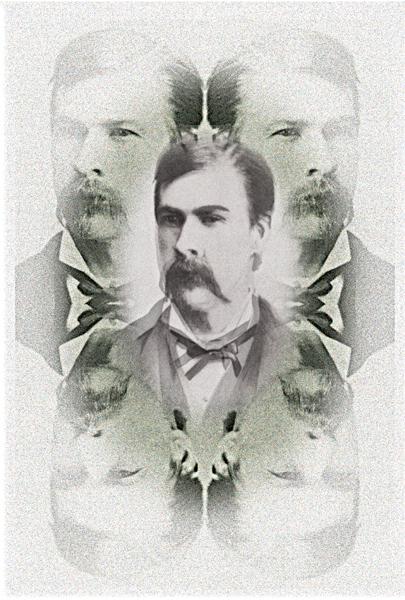

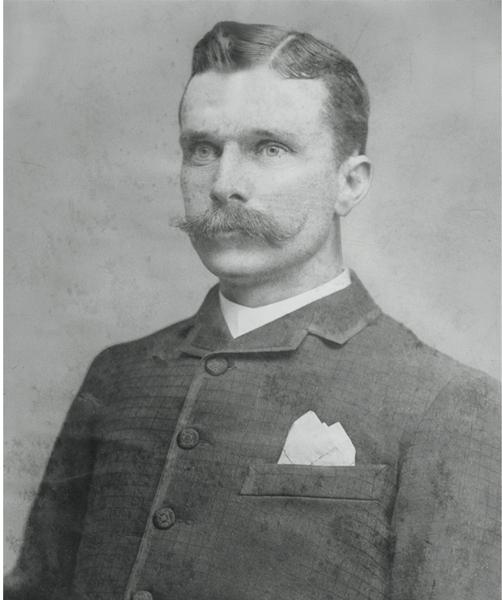

In 1907, Bat Masterson wrote an article on Holliday in Human Life magazine that included what is still a mystery photo (above). It is cropped below the neck and around the head, and appears to have been cut from another photograph, perhaps from a group photo. The hairline, eyes and chin have been retouched.

The original has never been found, and although the image has been published countless times, all versions apparently derive from the Human Life photograph. Author Stuart Lake used it in Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, with this caption: “This photograph, made by C. S. Fly in Tombstone, 1881, was the only one Doc Holliday ever had taken.”

After Lake’s book was published, Noah Rose further doctored the photo. Rose’s version (left) began to appear frequently; other photos claiming to be Holliday also appeared, primarily because someone thought the subject “looked like” Rose’s photo of Holliday.

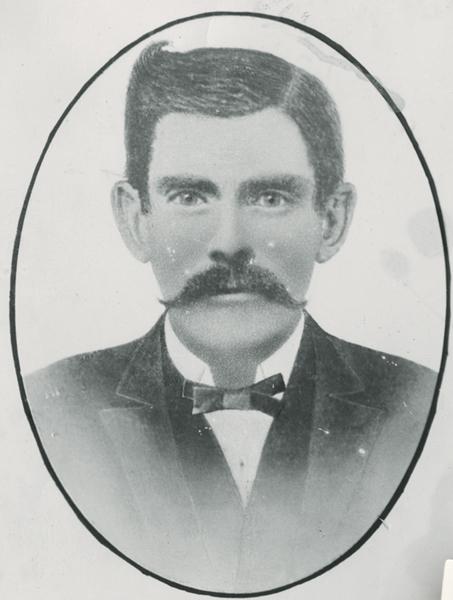

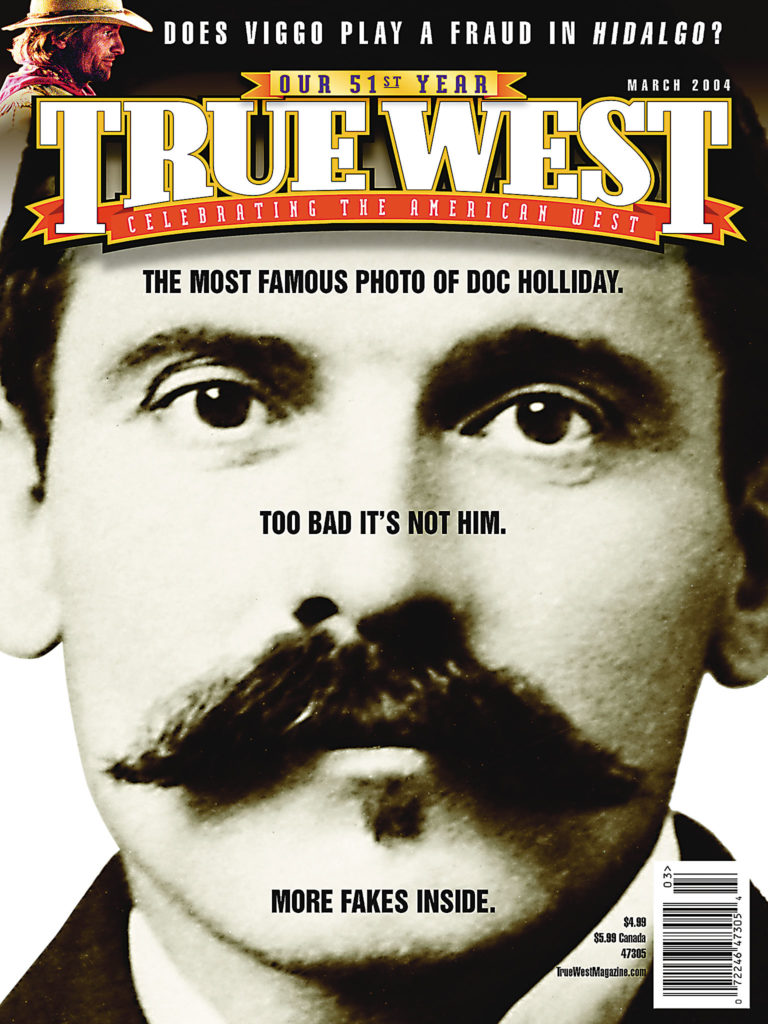

Another popular photo of Holliday (above) isn’t him at all. Rather, it’s a handsome guy with an imperial (a tuft of hair growing under the lower lip). Val Kilmer and Dennis Quaid used this likeness in their portrayals of Holliday in the movies Tombstone and Wyatt Earp.

A copy of this photo was presented to the Arizona Historical Society after being discovered in a family album of someone who “had been a mining engineer in Tombstone in the 80s.” The AHS then filed it as Doc Holliday and supplied it to numerous people requesting his picture.

Since then, the individual in the photo has been identified as John Escapule.

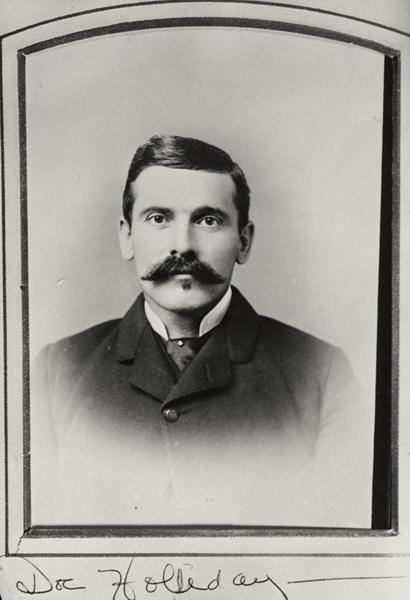

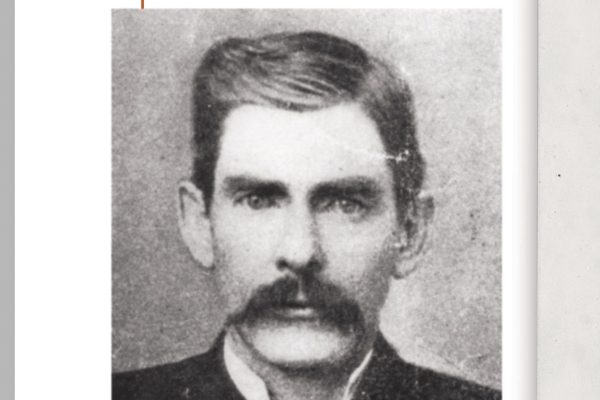

In 1973, the Holliday family released a portrait photo of Doc that had unquestionable authenticity (below). He had given it to his cousin Mattie, and it shows what he looked like at age 20.

When this photo surfaced, some historians began to question the photo used by Masterson in 1907. But wouldn’t Masterson have known if his photo was of Holliday? They knew each other. And wouldn’t Stuart Lake have discussed the photo with Wyatt Earp?

When the retouching is removed from both Rose’s and the Human Life photos, the resulting image looks, in my opinion, much closer to the authentic photo of the 20-year-old Holliday.

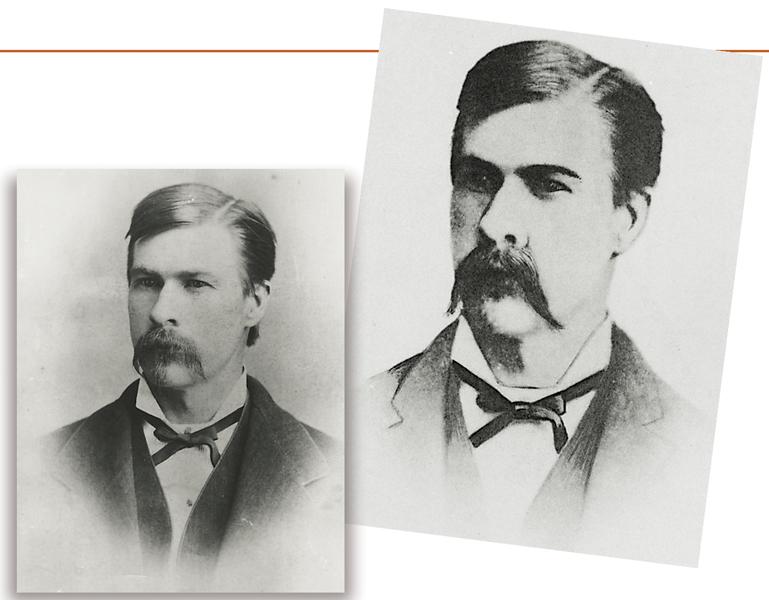

In his book, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, Stuart Lake includes portraits of Morgan and James Earp that he obtained from the Earp family. Here is Morgan Earp’s photograph (left) next to the same photo with Noah Rose’s alterations (right). Despite some historians’ claims that both images are pencil drawings, the left image is definitely a photo.

This photo of Zee James with her two children was taken a few days after Jesse was killed. A comparison of the two images shows that the women don’t resemble each other. In my opinion, the stage picture is an actress playing the part of Mrs. Jesse James. Theatre patrons may have been misled into believing the actress was the real wife of Jesse James.

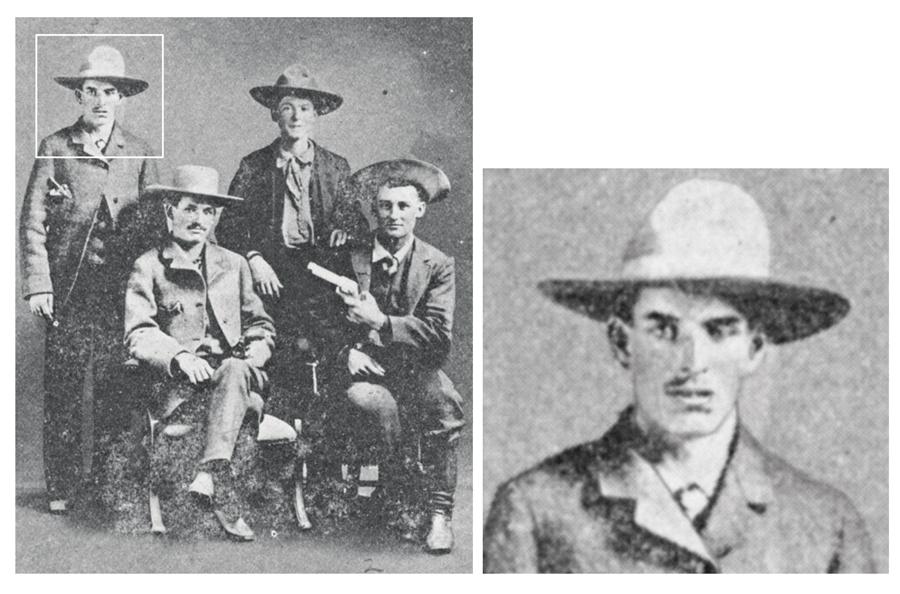

For years, historians have been frustrated over the lack of a photo showing Texas’ most famous outlaw, Sam Bass. Wayne Gard’s 1936 biography about Bass states, “No authentic picture of Sam Bass is known to exist. Several purported photographs of the outlaw leader are in circulation, but these have been discredited by his relatives and acquaintances.” Nonetheless, writers continue to use inaccurate photos.

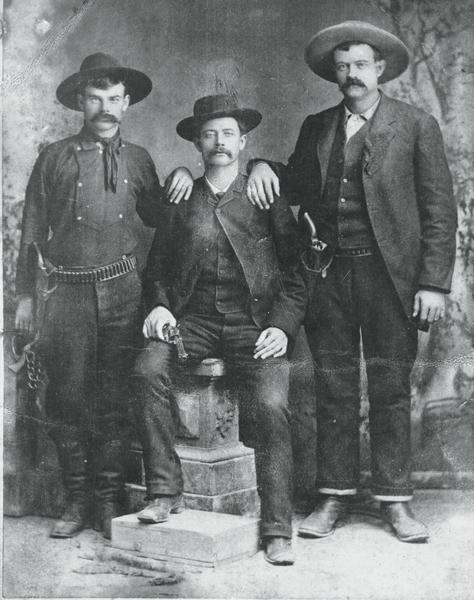

This commonly used photo (left) identifies Bass as the seated gentleman. The big guy on the right is usually reported to be Jim Murphy, with Seaborn Barnes on the left—both were members of Bass’ gang. As early as 1951, Hunter and Rose, in The Album of Gunfighters, correctly identified the men as: Sam Walker (right), Thomas O. Bailey (center) and someone remembered only as “Kid” (left).

At right this image is the most widely used Sam Bass photo. I suppose it shows how we would prefer Bass to have looked. Recently, a producer of a TV show on Old West outlaws contacted me for some photos. I sent him an authentic photo (see below), but it didn’t have the look he wanted. I sent him a copy of this misidentified one, but told him it was not Bass. He liked the fake better and used it.

This photo of Bass does, however, fit the descriptions given by people who knew him: “quite as poor a prospect for a hero as ever blossomed into notoriety”; “stooped in his shoulders, and wore a downcast look”; “a sort of Roman nose, a Jewish caste of countenance”; and weighing about 135 pounds.

Although this photo was first published in 1924 in The Black Hills Trails by Jesse Brown and A.M. Willard, it was labeled only “Gang of Outlaws.”