A tourist at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado isn’t impressed.

A tourist at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado isn’t impressed.

Isn’t impressed by the torched scenery. Isn’t impressed by the history.

“I was expecting more,” the tourist says. “They make such a big deal out of the Anasazi, but look at how they were living. At the same time, the Renaissance was beginning in Europe.”

Sometimes, I want to kill tourists.

Sure, the scenery is charred, but what do you expect after a slew of forest fires combined with drought? And how can you not be impressed by the wealth of history in the Four Corners region, where the borders of Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico meet?

Besides, let’s get our history straight. The Renaissance began in Italy in the 14th century before spreading throughout Europe; the Classic Pueblo Period lasted from A.D. 1100 to 1300. And with apologies to Michelangelo, the people who inhabited this area, the Anasazi (Navajo for “ancient ones”), were artists in their own right. They made spectacular black-on-white pottery—without a potter’s wheel, no less—turquoise jewelry and woven clothing. And they built buildings—entire cities—that each year draw tourists, archaeologists and history buffs by the thousands.

Using Mesa Verde as my base camp, I plan on checking out this history, soaking up the art and mystery (what happened to these ancient ones?), and enjoying it all—ignorant tourists be damned.

New Mexico heritage

Trail of the Ancients Scenic Byway is one way to learn about early Pueblo Indian culture, with 23 stops beginning at the Four Corners Monument and ending at Arizona’s Canyon de Chelly National Monument. Trail of the Ancients, however, disses New Mexico, and there’s a wealth of history to be found there.

So before I explore the wonders of Utah and Colorado, I’m traveling south from Mesa Verde. (I’ll have to skip Arizona’s offerings due to schedule and gas constraints, but if you have time, Canyon de Chelly and Navajo National Monument are well worth a visit.)

Count on a long day trip (or two) to get a handle on the New Mexico history of the Anasazi. Better make that “Ancestral Puebloans,” which is what their descendants prefer we call them.

My first stop is at Aztec National Monument in Aztec to tour the West Ruin, an excavated great house with 400 rooms around the plaza. Built between 1111 and 1121 with a Chaco Canyon-culture influence, it was one of the largest communities in the Animas River Valley. Aztec boomed but began to decline around 1130 when a lengthy drought settled over the valley.

Sometime in the 1200s, it was remodeled by people showing a Mesa Verde influence, and another great house, now dubbed the East Ruin, was begun. By 1300, however, the inhabitants had moved on. Drought may have been the cause, but science has yet to find conclusive evidence of what drove these Ancestral Puebloans away.

The highlight at Aztec is the Great Kiva, the subterranean lodge where the most holy of ceremonies were performed. To the ancient ones, the kiva symbolized the womb of the Earth Mother. In the middle of the kiva was the sipapau, the earth’s navel, the passageway to the underworld. Kivas can be seen at a myriad of ancient Pueblo ruins, but Aztec’s is special.

Archaeologist Earl H. Morris excavated the Aztec kiva in 1921 and rebuilt it in 1934. It’s the Southwest’s only recon-structed great kiva. I enter the kiva with respect for Morris, who gave us insight into the ways of these ancient people, and for the Puebloans themselves. It’s not the Sistine Chapel, but you do feel a presence here.

Another set of ruins is found off U.S. 64 just west of Bloomfield. Salmon Ruins and Heritage Park features the remains of a two-story pueblo, origin-ally built between 1088 and 1093, abandoned around 1130 and then reoccupied in 1185.

The Heritage Park has reconstructed “habitations” of various cultures from the Four Corners region, as well as a pioneer homestead, and the small park attracts 10,000 tourists a year.

It’s also a whole lot easier to get to than my next stop.

After driving 27 miles southeast of Bloomfield on U.S. 550, then about 30 miles on an unpaved road from Blanco Trading Post, I park my dust-covered Pathfinder in front of the visitor’s center at Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

Keep in mind that Chaco is remote, with few amenities, so come prepared with food and gas. This is desert, so drink plenty of water, which is available at the visitor center.

The Chacoan settlement thrived between 850 and 1250, and the ruins astound many. Maybe they didn’t have Raphael of Urbino painting The Marriage of the Virgin, but they built a commercial hub without blueprints and diesel earth movers. They must have had some sort of planned design for their towering pueblos, because they combined skills in geometry, astronomy, landscaping (drought tolerant, naturally) and engineering in order to construct these great buildings.

Another part of Chaco history, though, is found in a graveyard near Pueblo Bonito.

Richard Wetherill, who discovered Mesa Verde’s Chapin Mesa with Charles Mason in 1888, arrived in Chaco in 1895. As an excavator and trader, Wetherill had few morals, and it was his controversial form of archaeology—more tomb raider than scientist—and lack of respect for American Indians that led Congress to pass the Antiquities Act in 1906. Wetherill was killed by Navajos in a mysterious argument in 1910, and he was buried in Chaco.

The act that Wetherill’s disrespect brought about protected historic and prehistoric sites on public land. President Teddy Roosevelt designated Chaco a national monument in 1907. And in 1980, Chaco was redesignated a national historical park.

Utah’s history

Rested, restored and back in Mesa Verde Country, I take off for Utah, first stopping at Four Corners Monument, the only U.S. site where four states meet at a single point. From there, it’s easy to backtrack to the town of Bluff via highways 41; 262; 163 and 191.

Spend some time in Bluff, founded in 1880, and check out nearby Sand Island. Just don’t look for an island. You won’t find one. What you will find, most likely, are San Juan River rafters and a petroglyph panel displaying 800 to 2,000-year-old rock art.

From Bluff, travel north on 191 to another old Puebloan site at Edge of the Cedars Museum State Park near Blanding, which houses Pueblo, Navajo, Ute and white pioneer artifacts.

South of Blanding off Highway 95 are the Butler Wash Cliff Dwellings, and if you have time, the 17-mile drive through the Valley of the Gods is spectacular, though hard on your vehicle’s shocks. Afterwards, double back to 191 and head south, turning east on 262 until you reach Hovenweep National Monument on the Colorado border.

Six ruins are found at Hovenweep, all built around 1200. Hovenweep is overshadowed by Mesa Verde’s offerings but important because of the monument’s range of unique towers: square, oval, circular and D-shaped. The easiest ruin to visit is Square Tower. Other sites require some hiking. Remember: snakes have the right of way.

Mesa Verde country

Since we’re back in Colorado, drive northeast on unimproved road 10 (bearing good road conditions) to the 12th-century Lowry Pueblo before heading back to Mesa Verde.

Two other sites worth checking out include the Anasazi Heritage Center, a museum and research center in Dolores, and Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, which offers hands-on excavation programs north of Cortez.

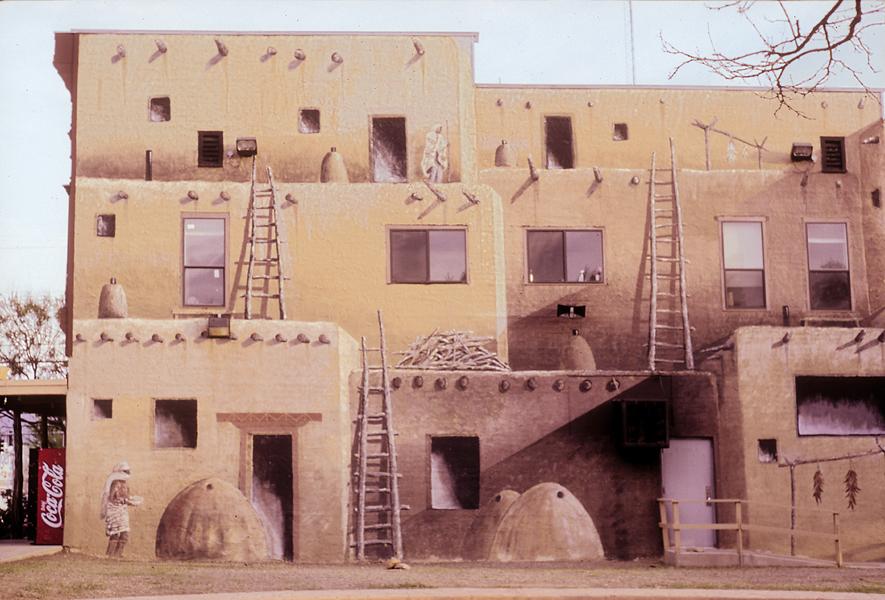

You may be surprised by Cortez. For a small town, it offers intriguing shopping and even greater grub. An exterior Pueblo mural decorates the circa 1909 Cortez Cultural Center, which not only features Pueblo and other Indian exhibits, but also lives up to its “cultural” claim with Indian dances and other programs held during the summer months. Perhaps you’ll also be lucky enough to catch Sharon French’s one-woman play, “Black Shawl.”

Of course, Mesa Verde National Park is just down the road.

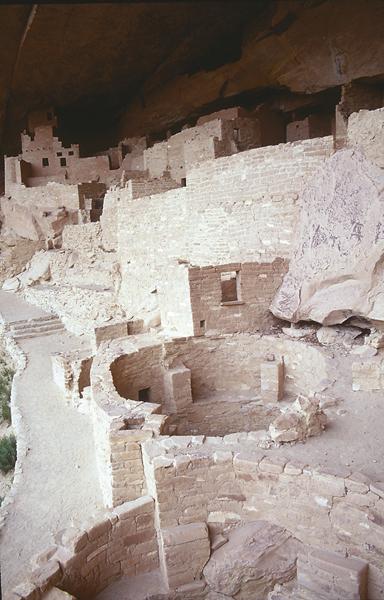

The villages found in this 52,036-acre park were built between 450 and 1300. History does repeat itself. Like Americans today, these folks traded up in their homes, moving from pit houses to rough pueblos to stone buildings, and creating entire cities built in caves.

I take the guided hikes through Cliff Palace and Balcony House, or, as park ranger Skip Denner calls the latter, “Bang Your Head House.” After all, the people who lived here 800 years ago were a long way from being 5’11”. Pueblo women were about 4’3”, the men 5 feet.

Other ruins include Spruce Tree House, Square Tower House, Sun Point Pueblo, Sun Temple and Wetherill Mesa. The excellent park museum is where you go to pick up tickets for the Cliff Palace and Balcony House tours.

Luckily, I’m at the park during the weeklong Indian Arts and Western Culture Festival, which kicks off each Memorial Day and includes a Navajo rug auction, an Indian Art Market, concerts and seminars.

I’m especially glad to head south from Cortez on U.S. 160/666 to Ute Mountain Tribal Park and tour Porcupine House, which is open only once a year during the summer. Ute Indians guide these tours—self-guided tours are prohibited—and I learn a different perspective on the Ancestral Puebloans from my guide, David L. Wells.

Trained archaeologists may frown on how artifacts such as pottery shards are laid out in groups, but the Ute Way is respectful to Pueblo culture. In short, Wells is no Richard Wetherill. As we descend into the 62-room, four-kiva Porcupine House, which possibly housed 186 people, the tourists with me adopt, at Wells’ suggestion, the Ute Way. Wells tells us:

• Before descending a ladder: “The Ute Way is to hug the ladder and say, ‘Take me down safely.’”

• When dealing with heat: “The Ute Way is always call the wind. If we don’t, it will die, and we will perspire more.”

• And crossing paths with snakes: “The Ute Way is to never think about reptiles.”

I don’t know what the Ute Way is to deal with obnoxious tourists, but I don’t have to worry about it. Everyone shows reverence on this tour. Even a tourist who prefers the European Renaissance will probably come away with an appreciation for what it took to survive the Four Corners centuries ago. These ancient ones had art and culture that even a 14th-century Italian would likely have appreciated and admired.

Johnny D. Boggs is a novelist and freelance writer and photographer in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Though tempted, he neither maimed nor killed any tourists during this trip.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs –