August 25, 1896

Riding with a six-man posse that includes the deadly Dunn brothers, U.S. Marshal Heck Thomas meets two informants (the Noble brothers, Tom and Charles) outside of the crossroads settlement Lawson, Oklahoma.

The rendezvous has been prearranged for sundown, just “beyond” the village.

With the informants in tow, the posse members make their way to the west end of the tiny berg. They are after Bill Doolin, who has been on the run since his spectacular break from the Guthrie federal jail on July 5.

Moving stealthily, the posse takes position in a cane break straddling both sides of a dirt road leading west from the crossroads (see overview, opposite page). Meanwhile, Marshal Thomas crawls up on a hilltop and scouts the village with field glasses.

At the posse’s approach, the Ellsworths’ dogs begin barking. Since the Noble brothers have a blacksmith shop near the Ellsworth store, Doolin tells his wife “That must be those God damned Nobles. I’m going out and run them off.”

Leaving Edith by the loaded wagon, Doolin walks his horse west along the country lane leading from the Ellsworth barn. In the moonlit darkness, he carries his Winchester and peers into the foliage on both sides of the road. When Doolin approaches the cane break at the bottom of a small hill, Thomas cries out “Halt!” A voice from the other side of the road yells, “Stop! Throw up your hands!”

Doolin shoulders his Winchester and fires toward the voices. He then drops his rifle (there’s evidence it was shot out of his hands) and snaps off several quick shots with his revolver.

A volley of Winchesters firing from both sides of the road replies, followed by the boom of a double-barrel shotgun. Doolin is riddled with buckshot and “razed” to the ground.

The fight is over.

The Heck Thomas Version

“We waited a long time without seeing anyone, although there was considerable stir about the store and dugout. We learned afterwards that Doolin’s wife had told him some of the neighborhood boys had been spying around there too much and that someone was around that night. Finally [Doolin] came out of the stable and to our great surprise, started down the lane coming west, you know how the store is situated on the high prairie…. If Bill had wanted to have made his escape he could have had open roads north, south, east, northeast, or … northwest through the pasture to those high hills that you have seen many times. Well, he came right down the lane leading his horse by the tip ends of the bridle reins, walking slow in the bright moonlight, Winchester in both hands, well out in front of him, nearly in position to shoot. He was sure on the prowl … looking first to one side and then the other … for the neighborhood boys who had been spying on him. Then I hollowed to him and had one of the other boys on the other side of the road to hollow to him…. He shot at me and the bullet passed between me and B. Dunn. I had let one of the boys have my Winchester and had an old No. 8 shotgun. It was too long in the breech and I couldn’t handle it quick so he got another shot with his Winchester and as he dropped his Winchester from [a] glancing shot, he jerked his pistol and some of the boys thought he shot once and the others twice—and about that time I got the shotgun to work and the fight was over.”

—Heck Thomas, in a letter to Bill Tilghman, September 3, 1896

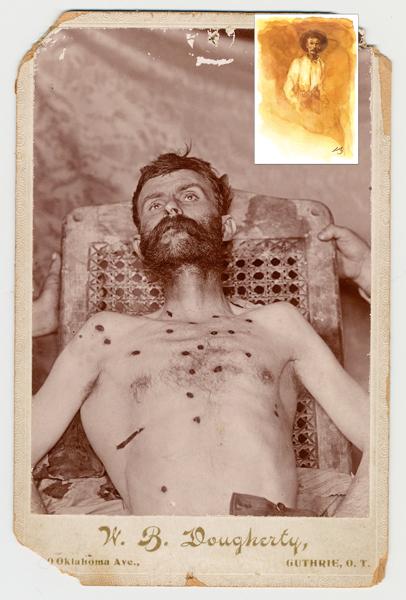

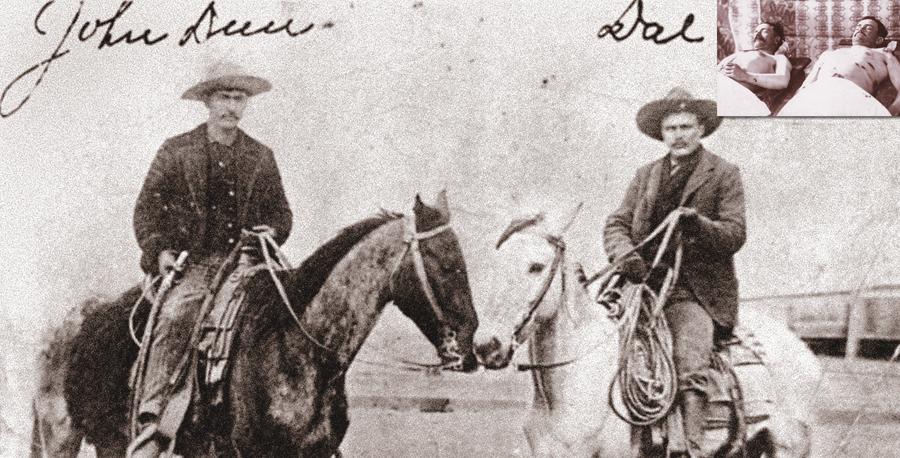

A Dark and Persistent Rumor Stalks the Dunn Brothers

After the killing, a wagon was procured from the Hoke farm (see map, p. 41) and the dead body of Doolin was carted back to Guthrie to be photographed for the reward (see photo, p. 44). Because Doolin’s corpse had an absence of bloodstains when it was delivered to the morgue, rumors claimed the outlaw had died a natural death, was set up against a tree (one version says a “corn shock”) and filled with buckshot in order to “make believe he had been killed.” Another version claimed Doolin died of “galloping consumption” and was then shot. Actually, Doolin had “bled profusely” and was cleaned up for the photo at W.B. Dougherty’s photography studio.

The dark rumors undoubtedly gained credence because the Dunn brothers (right) were notorious for playing both sides of the law. Having ridden with the Daltons and Doolin on the Owlhoot Trail, they abruptly switched sides. Prior to the Doolin shooting, they had killed two other fellow gang members, George “Bitter Creek” Newcomb and Charley Pierce, while they were guests in the Dunn home. Killed for the reward, the dead outlaws had buckshot in the heels of their feet, leading many to infer they were shot as they slept.

In the aftermath of the Doolin shooting, members of the Thomas posse were reluctant to say who had used the shotgun. Some historians maintain that one of the Dunns fired the fatal shotgun blast that brought down Doolin, adding that Thomas only claimed to be the shooter because it would be easier to collect the reward.

Subscription Forwarded to Hell

Returning from a successful train robbery with the Daltons, Bill Doolin met a newspaperman on the trail. After asking about lawdogs on the backtrail, Doolin rode on but then turned and asked how much a subscription to the paper cost. Informed a one-year subscription was a dollar, Doolin reached into a “shot sack,” scooped out a handful of stolen silver dollars and threw them at the journalist. Dismounting and picking them up, the scribe informed Doolin they would pay for 11 years and then asked him where he should send the paper. The outlaw laughed and told him to send the paper to Ingalls until he was dead, and thereafter, to hell.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

In spite of posted rewards for Bill Doolin that reached $5,000, when it came time to pay up, Heck Thomas got only $1,425, which he split among the posse members. After paying a lawyer to write up the “applications for reward” and two stenographers and the expense of a half-dozen trips to Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas in order to facilitate the collection of the above reward money, lawman Thomas was “out of pocket,” meaning he had spent more money than he received.

There were only two mourners when Bill Doolin was buried on August 29: his wife Edith and a family friend. A twisted, rusty buggy axle was thrust into the ground for a grave marker. Edith Doolin filed a $50,000 damage suit for the “unlawful death” of her husband but later withdrew it.

Edith soon remarried and Doolin’s son Jay took the name of his stepfather (Meek). Jay lived in Ponca City, Oklahoma, and worked for an oil company before retiring at age 65. He once wrote, “I have never been arrested for a crime, nor has any one of my children. This is not true of some of the Oklahoma Territory marshals. Although Bill Doolin was never praised for his law enforcement, he never had an outlaw son.” Jay was coyly referring to lawman Bill Tilghman’s nefarious sons (two were lifelong criminals and a third died from gunshot wounds while trying to hold up a crap game).

Photo Gallery

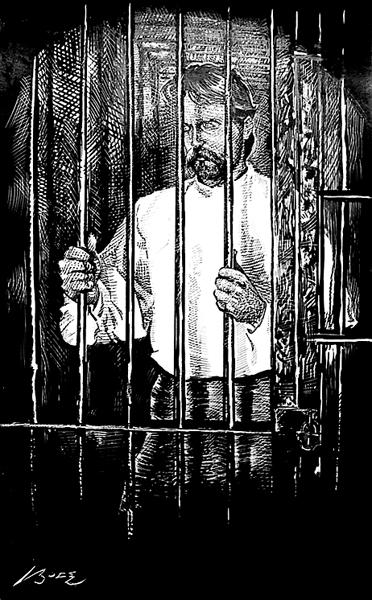

On Sunday, July 5, 1896, at 8:45 p.m., a prisoner in the “bull pen” of the Guthrie federal jail asked a guard to move a bucket of water closer to the cells. When night guard J.T. Tull leaned over to move the bucket, prisoner George Lane reached through the bars and grabbed the guard, holding him as three others disarmed him and got the keys. Once out of his cell, Bill Doolin (above) grabbed another guard’s pistol from a box and, along with eight other prisoners, made his escape into the darkness. For the rest of his movements, see map at right.

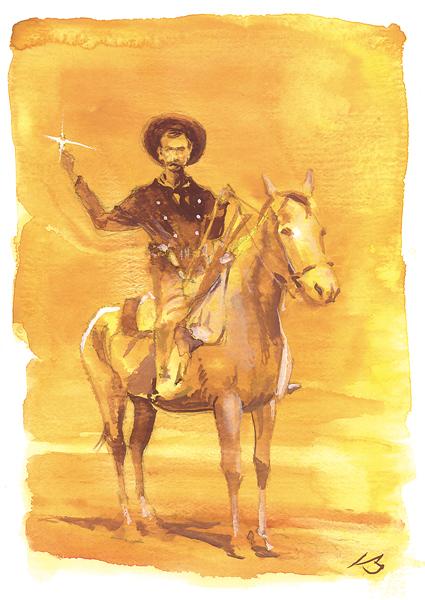

At six feet two inches tall and a mere 150 pounds, outlaw Bill Doolin (left), was a stringbean cowboy with auburn hair, blue eyes and reportedly wore a “ragged brindled” mustache. A respectable cowboy until the early 1890s, Doolin quickly became a notorious desperado charged with many crimes, including murder, rustling, selling whiskey to the Indians and knocking over three banks and seven trains.

He robbed several trains with the Dalton brothers, including the train in Adair, Oklahoma, on July 14, 1892. The robbery resulted in the wounding of three lawmen and two civilians, one of whom died.

Shot in the heel during a chase by Chris Madsen and eventually captured by Bill Tilghman in January 1896, the “king of the outlaws” was greeted by a large crowd when he was brought to Guthrie for trial. He escaped jail on July 5 and finally came face-to-face with the third guardsman, Heck Thomas, in a cane break. The results were not pretty (above).

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

– Morgue photo courtesy Robert G. McCubbin; Dunn Brothers photo True West archives –

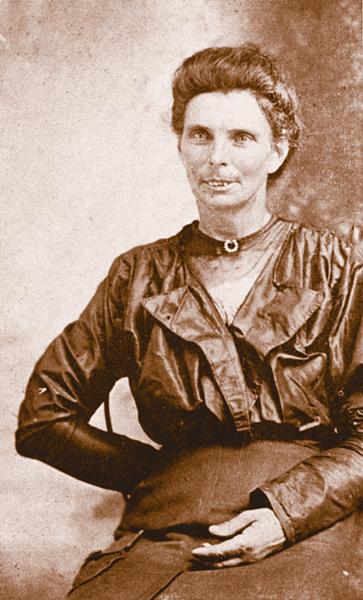

Outlaw Bill Doolin fell in love with a Methodist minister’s daughter who was working at the O.K. Hotel in the outlaw stronghold of Ingalls, Oklahoma. After courting for several months, Edith Ellsworth (left) and Bill eloped to Kingfisher, Kansas, and on March 15, 1893, they married.

Born in Marshalltown, Iowa, in 1873, Edith was one of 13 children, only nine of whom survived to adulthood. At five feet six inches tall, Edith Doolin weighed a little over 100 pounds, had dark, penetrating eyes and “moved with a decisive step—with the air of one who knew what she was about.” She stood by her outlaw husband, defending and protecting him to the end.

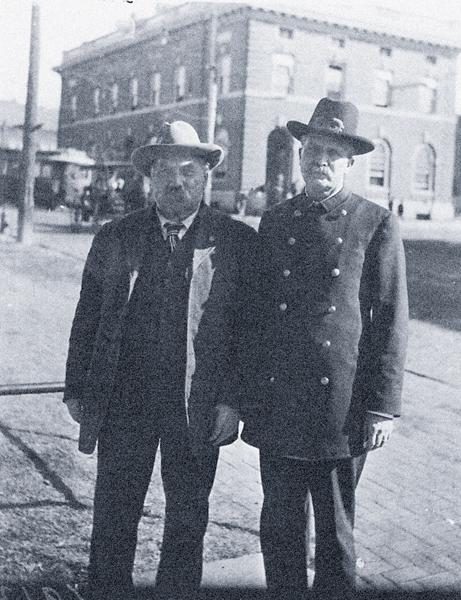

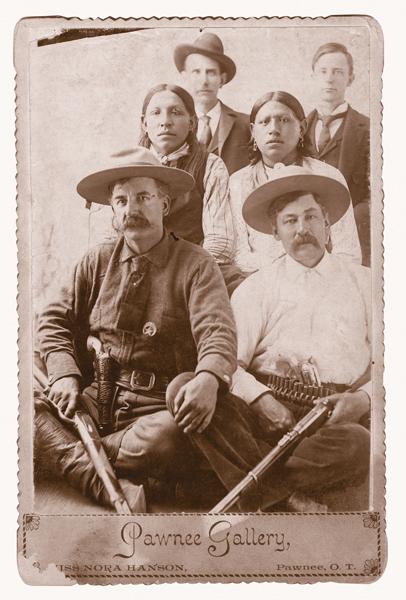

A lawman from the age of 18, Henry Andrew “Heck” Thomas (front row, left) wore a U.S. marshal’s badge at the time of the Doolin slaying. Known as the “three guardsmen,” Thomas, Chris Madsen and Bill Tilghman helped clean out most of the Doolin-Dalton Gang. Thomas was wounded a half dozen times in his storied career. He died of Bright’s disease on August 15, 1912.

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –