Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s Corps of Discovery passed the first winter of their epic 1804-06 expedition on the northern banks of the Missouri River in what is now North Dakota.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s Corps of Discovery passed the first winter of their epic 1804-06 expedition on the northern banks of the Missouri River in what is now North Dakota.

They built a small triangular encampment across the river from a friendly Mandan village. Other Mandan and Minnetaree villages were located a few miles upstream. It proved to be a cold season.

In his journal, Lewis marveled at the Indians’ fortitude in extreme temperatures, which got more than 40F below zero. He recounted how a 13-year-old boy experienced only frostbit feet after spending a cold night in the open air protected only by a buffalo robe.

In another entry, Lewis wrote how an Indian mother, threatened by a raging prairie fire, covered her toddler with a fresh buffalo hide when she realized she couldn’t outrun the blazing inferno carrying the boy. “She returned and found him untouched,” he wrote, “the skin having prevented the flame from reaching the grass on which he lay.”

This was 160 years before the first mylar survival blanket.

Northern latitude winters have always posed a formidable threat to human survival. Dangerous weather caused or contributed to more deaths among whites flocking to the American West than Indians, bandits and wild animals altogether. As for the Indians, they had no knowledge of textile arts and, therefore, no access to cloth. They adapted to freezing temperatures and wind-driven snowstorms by wrapping themselves in the skins and hides that protected animals from the elements.

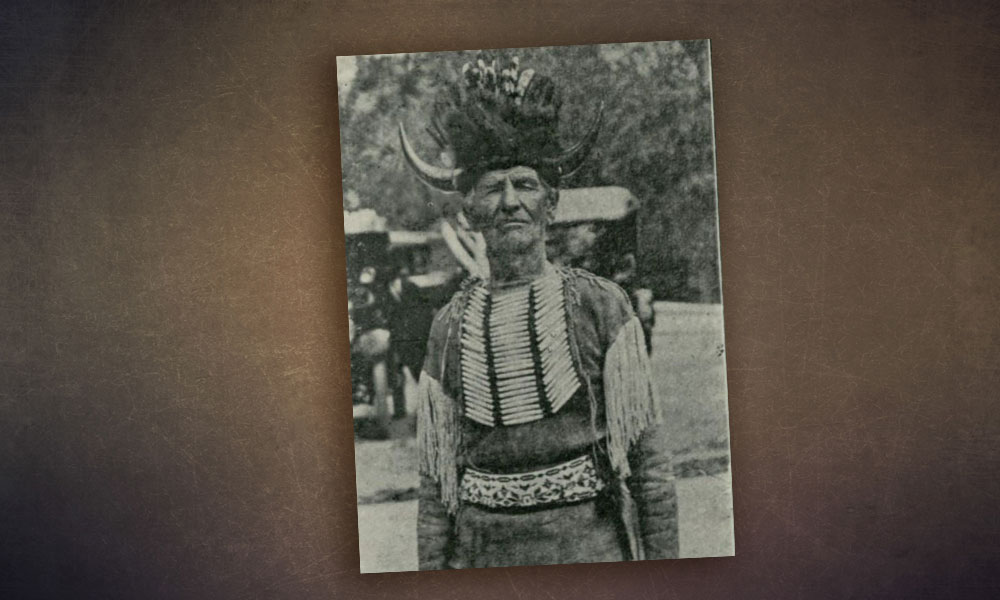

The first European trappers and traders venturing into the frontier adopted the ways of the indigenous tribes, not only to seek accommodation and acceptance among the natives, but also to survive the rigors of extreme weather as their woven apparel either wore out or was traded away.

Buffalo hides were particularly prized as “coat-worthy” due to their larger dimensions, thicker skins and dense, heat-retaining fur. A buffalo hide is still known as a “robe”—possibly because of the way Indians wore them draped over or around their shoulders. White trappers and traders interacting with the Indians added sleeves and buttons—sometimes collars and pockets—and turned the robes into coats.

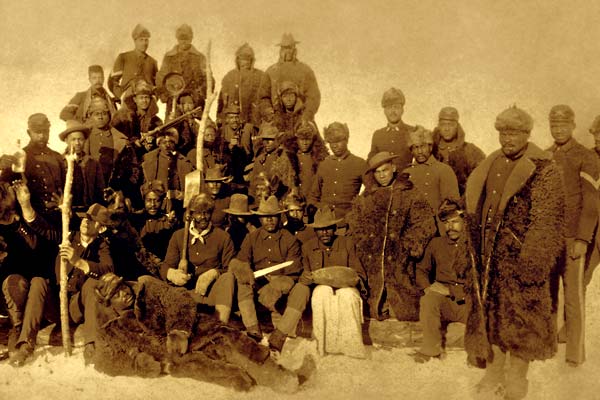

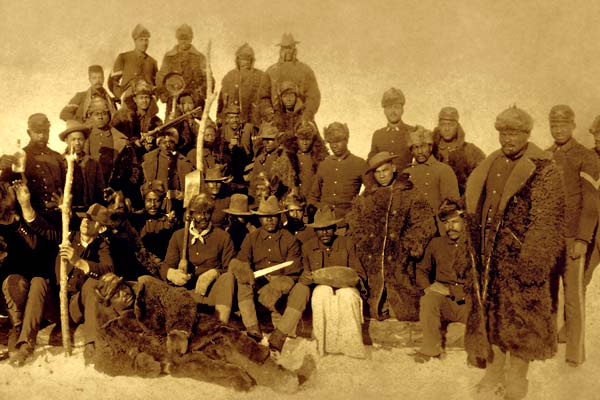

Cowboys, settlers and soldiers in the northern plains and mountains turned buffalo hides into vests, leggings, chaps, hats and coats until the herds all but disappeared. As late as the 1890s, soldiers and cavalrymen photographed in Wyoming wore the distinctive fur coats. Buffalo robes became a fashionable accessory among 19th-century Americans and Europeans who used them as blankets in their carriages and sleighs.

Despite modern-day protests from vegans and animal rights activists, fur coats, fur vests and fur trim on leather or cloth coats continue to be popular among the well-heeled. Buffalo coats are relatively rare, but they are available from a handful of specialty companies. A high-quality buffalo coat can cost upwards of $5,000, but it just might save your life in a blizzard—or a prairie fire.

G. Daniel DeWeese coauthored the book Western Shirts: A Classic American Fashion. Ranch-raised near the Black Hills in South Dakota, Dan has written about Western apparel and riding equipment for more than 25 years.